Earned Value Management - EVM

Contents |

Abstract

Earned Value Management is a very powerful and popular project monitoring tool. Monitoring and controlling are key practices in project management, serving the purpose of informing the project managers on the advancement of the project. They take as inputs the results of the planning process and investigate if the plans are being implemented in an anticipated way. In this context, Earned Value Management is mainly used in highly complex environments like construction and infrastructure and allows for a combination of time and cost controlling (ISO 21500), therefore guaranteeing a more holistic overview of the project advancement than other monitoring tools.

This paper will firstly provide a description of the tool and its purpose including formulas and essential vocabulary. Then, it will provide a framework on how to apply this method. Lastly, it will look into its limitations, and explore the reasons why it is mainly used in very complex projects and environments [1]

Earned Value Management Overview

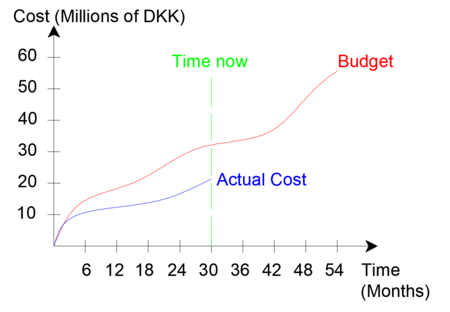

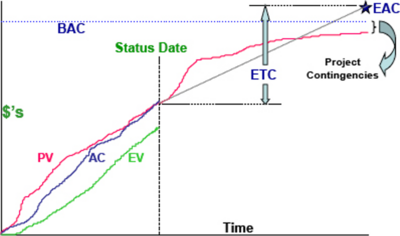

“How is your project going?” is a very frequently asked question to project managers and one it’s not easy to answer. As pointed out by Lukas, Joseph A. [2] one of the techniques that are frequently used in project management is comparing the planned expenditure curve with the actual one. However, this approach can cause major errors and provide misleading information. As projects are complex processes that involve a large number of aspects and dimensions, controlling just one of these dimensions is reductive. For example, in the case shown in Figure 1, it is not clear if the work is being accomplished with less money than anticipated, or if the project is behind schedule. The scope of earned value management is to provide a bi-dimensional tool, that is able to plot both the time and cost dimension of the project, therefore providing a more holistic monitoring method, that in one single graph contains a large amount of information on the project.

Terminology

As pointed out by Lukas, Joseph A. [2] it is important to clarify the terminology associated with Earned Value, as it is a source of confusion for many:

- Earned Value Analysis (EVA) — It is a quantitative method of assessing the progress of a project at any given point in time, predicting its completion date and final cost, and evaluating cost and schedule variances as the project progresses. Its objective is to assess whether the cost, schedule, and work done are progressing in accordance with the plan, comparing the expected amount of work done with what has actually been achieved. (Earned Value Analysis by Scott W. Cullen)

- Earned Value Management (EVM) is a project management methodology that uses an integrated schedule and budget approach and is based on a WBS to objectively evaluate project performance.

- Earned Value Management System (EVMS) — This is the method, processes, resources, and models that a company uses to implement Earned Value Management.

Earned Value Analysis formulas can be used on any project, but if an Earned Value Management methodology is not in place, it would be highly unlikely to produce accurate results. Moreover, in order to implement Earned Value Management, there must be an Earned Value Management System in place. The three concepts are therefore very closely linked to each other.

Earned Value Analysis : basic formulas and definitions

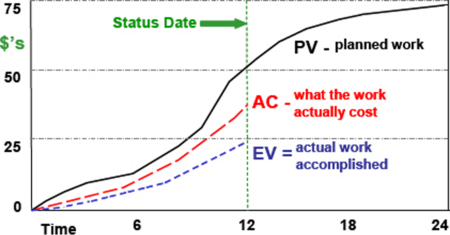

To carry out Earned Value Analysis, three key values need to be available: the planned value (PV), actual cost (AC), and earned value (EV). The first and second terms are the planned and actual expenditure cost, and should therefore be easy to obtain. The third term (earned value) is however more complicated to estimate as it measures the amount of value the actual activities completed have created. In detail:

- The Planned Value (PV) is the budget for the work achieved at given point in time [3].

- Actual Cost (AC), is the cost incurred for the execution of project work, also known as an actual expenditure. It can also be seen as the actual costs (AC) incurred to convert the planned value into the earned value [1] Sometimes it is referred to as the Actual Cost of Work performed (ACWP).

- Earned Value (EV) is the ratio of the total authorized budget actually completed at a certain date. This is also regarded as the budgeted cost of work performed (BCWP). EV can be defined by multiplying the budget for a work package or activity by the percentage of advancement: EV = percent complete x budget. [2]

Once the key parameters are established, and a measuring tool for each of these is defined, some more calculations can be carried out.

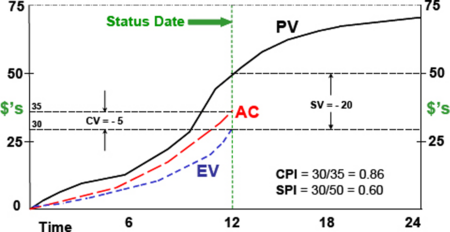

- Schedule Variance : SV = EV – PV.

- Schedule performance index : SPI = EV/PV. An SPI value of 1.12 means that 1.12 DKK worth of work was actually completed for each DKK of work that was planned to be done at this point in time. A SPI> 1 and SV> 0 suggest that more work was been completed at a certain date than what was scheduled. However, an SPI > 1.0 does not actually mean that the project is ahead of time

- Cost Variance : CV = EV – AC

- Cost performance Index : CPI = EV / AC. A CPI value of 0.97 signifies that 0.97 DKK is earned for each DKK spent. If the CPI<1 and CV<0 , the cost performance of the project is below what was planned.

Predicting with earned value management

SPI: Schedule Efficiency Indicator

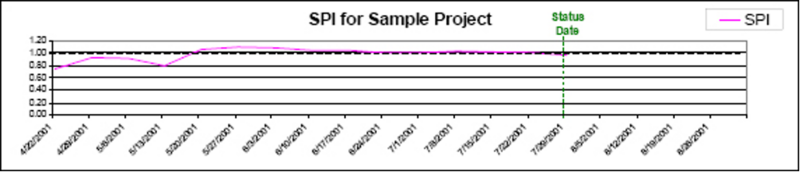

Figure 4 shows the SPI’s variation in function of time. SPI greater than 1.0 means that more work is done than expected, and an SPI less than 1.0 implies that less work is done than scheduled. A careful approach is important when using SPI, as, without taking into account how the team is doing against the critical path, the project health cannot be evaluated[1]. In this example, as the project is just starting up and activities are being initiated an SPI below 1.0 is measured for the first few reporting periods. However, if, after the first few reporting periods, the SPI does not progress towards 1.0, it is a sign of potential schedule issues and, thus, possibly indicates that it is necessary to take appropriate measures.

Calculating project expenditures using CPI

The Cost Performance Index is an ideal cost-efficiency metric for accomplished work. The primary use of CPI is to forecast the final cost of the project. As highlighted by Lukas JA. [2] a few definitions need to be specified prior to listing the typical formulas used:

- Estimate to Complete (ETC) is the estimated additional cost required for the project to be completed.

- Estimate at Completion (EAC) is an approximate total cost of the project at its completion.

- Budget at completion (BAC) is the complete authorized budget at completion of the project (including any project contingencies).

Most of the approaches for evaluating the EAC include a revision of the original cost estimate based on the performance of the project up to date. The formulas that are most common are:

- EAC1 = AC + (BAC - EV). This calculation is often referred to as the “overrun to date” or “mathematical” formula. This formula implies that the schedule will be executed as planned for the remaining work (CPI = 1.0). If a project is not performing well, this formula tends to be too optimistic.

- EAC2 = BAC/CPI. In some textbooks, this formula is called the 'cumulative CPI' and it means that the whole project can be carried out at the current value of cost efficiency (current CPI does not vary)

- EAC3 = AC + ((BAC - EV) / (CPI x SPI)) or BAC/(CPI x SPI). These formulas take into account the effect on the EAC on both cost and schedule and typically produces the most negative EAC for a project not performing well.

The significance of the CPI parameter is empirically proven to stabilize at the 20 percent completion stage of a project (with over 700 DOD projects studied)[4] Also, as the project progresses towards the 100 percent completion stage, the CPI metric becomes increasingly more stable. Stability is defined to mean that the final CPI does not vary by more than 0.10 from the value at 30% complete [2]

From Lipke W, Zwikael O, Henderson K, Anbari F. [5] it is shown that the 20 percent complete CPI stability is likely to be applicable only to extremely large long-term projects. It is therefore unclear whether small-project managers should expect accurate data from their use.

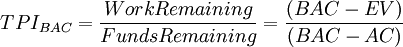

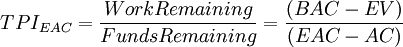

To Complete Performance Index (TCPI)

The To Complete Performance Index (TCPI) allows the project manager to estimate the necessary performance level of the remaining work, expressed in CPI, in order to complete the project on budget. This measure can either be referred to the authorized budget (BAC) or to the current EAC. TCPI provides a "sanity check" for the project manager on whether the required CPI for the remainder of the project is realistically obtainable. Of the two calculations, looking at the CPI required to complete the project based on EAC is considered to be more meaningful [2]. The two formulas for TCPI are:

Earned Value Management Application

Measuring PV, AC and EV

Progressing Techniques for Earned Value (EV)

In projects, it can be complicated to assess concrete advancement for Work Packages (WP), but it is important to ensure reliable and relevant earned value analysis. Obviously, quantitative methods are much better for assessing project progress than qualitative (subjective) techniques. When calculating project success, it’s important to remind ourselves that only an estimation. It is very common to spend too much time generating very precise values for Earned Value. But it is recommended to not spend too much time on estimating EV for small work package as its much more efficient to focus on the work packages with a larger value. As the nature of work packages in a project varies, no standard form of advancement reporting is appropriate. Below is a summary of the six most popular methods for monitoring project progress. [2] [6]

Quantitative progressing techniques are:

- Completed units: activities involving repetitive production of easily calculated pieces of work, where approximately the same amount of effort is needed for each piece.

- Incremental milestones. Job Packages (WP) can conveniently be separated into a series of sequentially managed tasks. The work is broken into separate, measurable tasks, and by completing each task, a 'incremental milestone' is considered to be reached. Progress is only achieved when a milestone is met.

- Start-finish is used for low-value and/or limited-duration tasks without clearly defined intermediate milestones. Either no or some minimal progress is made when the task is begun, and 100 percent progress is obtained at the end of the activity.

Qualitative progressing techniques are:

- Level of effort (LOE) is used when it is very difficult to calculate what work has been done for the allocated budget. It can be assumed that LOE is equal to the real budget-divided costs. For example, if the budget of the project manager on a project is US$20,000, and the project has been paid US$10,000, then progress is estimated at 50 percent.

- Individual judgment — mainly employed when the progress is not easily assessed with other tools. While it is a very subjective method, it can create a fair estimation of progress through having numerous perspectives by experienced team members on the work performed.

Other techniques:

- Combination techniques are suitable for complex work over a long period of time and use two or three of the methods listed above. Installing a building foundation can be an example. The excavation phase can be measured in completed units (removed cubic meters of earth), while the formwork can be assessed in completed milestones gradual milestones of formwork, and the concrete pouring with start-finish method.

If LOE is 10% or more of the overall budget, there is a strong risk of not having a precise calculation of the progress of the project.

The use of qualitative approaches to report project progress often causes team bias to creep into the progress measured. Therefore, quantitative estimation methods are strongly encouraged.

Cost collection (AC)

If you cannot obtain specific actual costs for your project, earned value will not produce correct results. Companies with numerous expense structures in use find it incredibly difficult to collect and record costs. A downside of cost systems is that they report only costs for invoices issued and/or paid. In general, any work contracted and any goods purchased would have invoices that delay a month or more from the completion of the work.

To get around this problem, Lukas JA[2] recommends to use an “adjusted actual cost” column for reporting actual costs (AC). “Adjusted actual cost uses the actual cost from your cost system, plus your estimate for outstanding invoices for work accomplished, which are called accruals” [2]. The project plan should include the expense monitoring process. This includes the frequency of the reporting and how the adjusted actual' costs will be measured and documented.

Planned value calculation (PV)

To determine the Planned Value, it is recommended to follow what is specified in the Methodology to apply Earned Value Management paragraph as this estimation is closely related to the framework for the application of EVM described below.

Methodology to apply Eaned Value Management

EVM requires that all work is identified, budgeted, and scheduled to the extent practicable. Therefore, the use of the earned value methodology must be properly planned. If not, the results risk being incorrect and the effort to obtain relevant measured can be extremely high. This is caused by the large amount of information that is needed to execute Earned Value Analysis, and that needs to be collected in an efficient manner. The key is to provide well-defined requirements and a good project plan, which includes the work breakdown structure (WBS) to thoroughly document the scope and the integrated schedule and cost estimate into the WBS. Here is the recommended procedure to successfully implement Earned Value Management [7] . This list is a summary of the 32 requirements detailed in the ANSI-EIA standard that explain the establishment of an Earned Value Management System (EVMS) and includes about 200 attributes for these 32 criteria.

1. The Basis - Deconstructing the Work Statement (SOW) of the project that determines the project scope into separate, observable components for the creation of the Work Breakdown Structure (WBS) listing the activities/tasks needed to carry out the project [7]. A WBS is a clear reflection of the project's work scope, describing the hierarchy and definition of the activities to be carried out and the connection with the deliverables of the project. The approved work scope is broken down by the WBS into suitable elements for planning, budgeting, scheduling, cost accounting [2].An increasingly detailed description of the project work is defined by each descending level. Based on the scope of the work, the WBS needs to be expanded to the extent required for project execution and control. There should be a single WBS number and organizational code for each task [8] .

2. Schedule the tasks in a logical way such that subsequent elements and the top level milestones are enabled by lower level schedule elements. The logic should also be driven by the critical path. Project schedules that do not refer to the WBS are a recurrent issue. The schedule of the project should have tasks corresponding to each WBS Work Package.[8]

3. Calculating the cost for the effort and resources to generate a precise budget for a project, also referring to the WBS activities and tasks. Through developing a project schedule and cost estimate that relates to the WBS, the project plan is integrating cost and schedule information. This makes plotting the Planned Value pretty straightforward.

4. Establish methods for assessing the achievement of work. The budget should be earned in the same way that it was planned (following WBS) [8]

5. Collect actual costs per discretized time periods per each WBS activity (AC)

6. Estimate the competition ratio of each project activity, using what was decided at step 4.

7. Manage the project through integrated control of cost and schedule variances, assessing final costs and duration, implementation of corrective measures.

The recommended workflow to implement Earned Value Management in the correct way is described above, however, to create a complete and well-functioning Earned Value Management System other aspects need to be taken into account.

- Change management process

There may be some concerns here, the most extreme being that the project team does not have a change management strategy in place. This topic should be discussed in the project plan. It must include the protocol for addressing adjustments in scope and variance, the forms for tracking and assessing proposals for change, the mechanism for examining and authorizing changes, and the process for ensuring that changes are implemented into the existing schedule so that the estimates of earned value remain useful[2]. Changes that exist but are not known may be the second potential problem area. The concern may be members of the project team who wish to add additional scope to the finished product and do not consider the cost or time added by those changes. If a change is accepted, the budgets for the tasks affected will be changed to:

Current Work Package Budget = Original Budget + Approved Changes[2]

- Quality check It is frequent that estimating and budgeting mistakes occur. This can be caused by poor communication, quantity discrepancies, or the use of incorrect prices. It is essential to have here is to have a quality management mechanism in place, which should involve reviewing the planning phase deliverables such as the schedule and the cost estimation by professional project staff.

- Management Support Management support for the process and not allowing management interference to impact the data is required to make earned value work. Management may have different motives for trying to affect what is published. EunHong Kima,*, William G. Wells Jr.b, Michael R. Duffey [9] pointed out management support as one of the top points for effective implementation of Earned Value management carrying out an empirical analysis.

Limitations

A large number of problems related to the implementation of Earned value Management arises from the large amount of information that needs to be provided, and that the majority of this information comes from estimation procedures. However, other frequently mentioned concerns such as " too high cost " and " too much paperwork " are no longer considered relevant by the literature. Instead, individual issues (e.g., incorrect evaluation of work done, and lack of EVM under-standing) and organizational-culture-related issues (e.g., a culture of mistrust and some pressures to disclose only good news) have been identified as major concerns[9] . Limitations also arise from the application environment of the methodology as it was originally conceived for large and complex projects (such as for the DoD), and it is still mainly used for these. Fleming QW, Koppelman JM.6 analyzed the reasons why it is not used on all projects:

1. The terminology used in the method has varied a lot in the years making the method seem more complicated than it is and somewhat unappealing.

2.The method was made overly perspective. Modern Earned value management was introduced by the airforce in the 1960s on the Minuteman project (highly complex). In order to preserve the concept, the airforce developed the C/SCSC (Cost/Schedule Control Systems Criteria), which was a project management system of 35 criteria that had to be met to use the method. Therefore, the requirements were too strict for a typical project manager to satisfy. Therefore, this concept was mainly used on governmental mandated major projects. Later, through a joint effort of the Dod and the private sector, the requirements were reviewed and published in the ANSIA-EIA 748, which still lists 32 requirements and is therefore too perspective for small projects. However, in 1996 PMI issued their PMBOK Guide, in this book the requirements are few and easily understandable. Thus, it is nowadays the minimal earned value standard and is applicable to any project and is compatible with ANSIA-EIA 748 (used on larger projects)

3. Optimism of project managers.

Some project managers resist the use of Earned Value management as they are repelled by the forecasts thinking it could become a self-fulfilling prophecy, instead of taking advantage of the early warning signals the method can provide, which can help project managers take actions at an early stage to keep the project in the planned track.

Annotated bibliography

Will be completed before next week

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Fleming QW, Koppelman JM. Using earned value management. Cost Eng (Morgantown, West Virginia). 2002;44(9):32-36.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 Lukas JA. How to make earned value work on your project. PMI® Glob Congr 2012—North Am Vancouver, Br Columbia, Canada. 2012;(5):1-9

- ↑ PMBOK Guide

- ↑ Fleming W. The Earned Value Body of Knowledge (EV-BOK). Published online 2002:19073.

- ↑ Lipke W, Zwikael O, Henderson K, Anbari F. Prediction of project outcome. The application of statistical methods to earned value management and earned schedule performance indexes. Int J Proj Manag. 2009;27(4):400-407. doi:10.1016/j.ijproman.2008.02.009

- ↑ Fleming QW, Koppelman JM. Earned Value Project Management. 4th edition. Project management institute; 2010.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Steps T, Value E. 10 Steps to Understanding Earned Value Management.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Chance W. Earned value management systems ( EVMS ) you too can do earned value management. Published online 2006:19073."

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Kim EH, Wells WG, Duffey MR. A model for effective implementation of Earned Value Management methodology. Int J Proj Manag. 2003;21(5):375-382. doi:10.1016/S0263-7863(02)00049-2