Getting Things Done (GTD)

Getting Things Done (GTD) is an integrated life-management system developed by David Allen in the late 1900’s and early 2000’s and first published in the book Getting Things Done – the art of stress-free productivity in 2001. The system incorporates a horizontal focus for processing, organizing and reviewing everything that requires attention through a Five Steps for Mastering Workflow, and a vertical focus for project planning through the Five Phases of Project Planning. Implementing and practicing the Getting Things Done methodology should result in the practitioners becoming more productive and creative by using an external memory and by obtaining a complete overview of current commitments and projects.[1]

The vertical focus of Getting Things Done will briefly be described, but the emphasis in this article will be placed on the horizontal focus going in depth with the practices as well as describe its limitations.

The described practices is based on the second and newest edition of David Allen’s Getting Things Done – the art of stress-free productivity published in 2015.

Contents |

Why use Getting Things Done?

The principle behind the practices of Getting Things Done is that the work and personal life of people are constantly changing and involves an information overload that no system can describe or coordinate. To cope with the complexity, Getting Things Done implements a full methodology for the users to manage current commitments while registering and organizing new opportunities or other items that requires attention in an external memory, [1] because "your brain is for having ideas not holding them". [2]

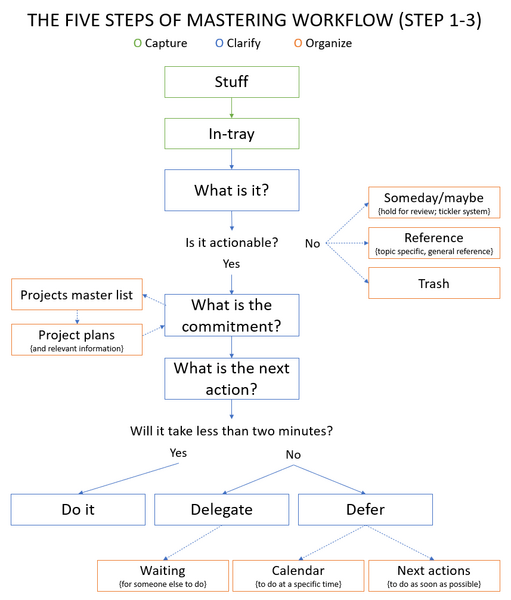

The practices of Getting Things Done are structured in a horizontal focus for every aspect of work and personal life and a vertical focus for narrowing down a single project. The horizontal focus is implemented through the Five Steps of Mastering Workflow: (1) to capture every item that has attention, (2) to clarify what the item means and what the next actions should be, (3) to organize the next actions in an external memory, (4) to reflect on the items in the external memory, and lastly (5) to make decision about what items to engage with.[1]

The vertical focus should assist the user in getting a project under control, finding a solution, or ensuring that the right actions are planned. The vertical focus is implemented using the Natural planning model and the Five Phases of Project Planning: (1) defining the purpose and principles, (2) outcome visioning, (3) brainstorming, (4) organizing, and (5) defining next actions. The focal point of this article will be the horizontal focus.[1]

The promise – mind like water

Allen argues for the need of an external memory since “there is usually an inverse relationship between how much something is on your mind and how much it's getting done”. [3] Thus, if someone is able to empty their mind from everything that requires attention, according to Getting Things Done, they should become more creative, productive, and confident in that everything they are doing at any time is exactly what they should be doing at that time. Therefore, by implementing the practices of Getting Things Done it should be possible to gain a mind like water: “Water is what it is, and does what it does. It can overwhelm, but it’s not overwhelmed. It can be still, but is not impatient. It can be forced to change course, but it is not frustrated”. [4]

The relevance for project, portfolio, and program managers

The standards for project, program, and portfolio management sets out specific responsibilities and set of skills required of a project, program, or portfolio manager. All the managers must be able to process a great amount of relevant and irrelevant information about the project, program, or portfolio, while ensuring that complex, dynamic and interconnected activities are executed and organized in an appropriate manner. [5] [6] [7]

The practices of Getting Things Done are both relevant for the managers’ work as well as their personal life. The Five Steps of Mastering Workflow offers a systematic approach for the project, program, or portfolio manager to process, store, and review items from the constant information flow in an external memory. In addition, will application of the practices ensure an active management of the interconnected system of activities by forcing the managers to think of the next action and to implement an overview of all delegated actions. Lastly, applying the practices to every commitment in the manager’s life will enable the manager to stay on top of things, empty the mind, and thereby become more productive and creative.

Horizontal focus – Five Steps of Mastering Workflow

The Five Steps of Mastering Workflow: capture, clarify, organize, reflect, and engage, are according to Allen already present in the way most people deal with things in their daily work and personal life. In the book Getting Things Done: the art of stress-free productivity Allen uses the example of someone expecting guests for dinner and coming home to a mess in the kitchen. The person would identify all the stuff laying around (capture), decide what to keep or what to put in place (clarify), put things away (organize), compare the recipe’s ingredients with what is on the shelves (reflect), and lastly get started cooking or go to the grocery store (engage). [8]

As shown with the example above the steps are rather simple and part of most people’s current workflow, but to receive the benefits of ‘mind like water’ the Five Steps of Mastering Workflow must be implemented in a structured and consistent manner as suggested by the methodology. Each step in the workflow has its own best practices and tools and must be conducted separately, and afterwards linked and integrated into the other steps.[1]

Each step of the workflow will be described below as if the reader is the user and illustrated in the Five Steps of Mastering Workflow diagram.

Capture

The step of capture is to move anything that has appeared in the mind or in your physical environment that requires an action or decision, the so-called stuff, from there and into an in-tray in the form of a placeholder. A placeholder can be a note, an audio-recording, an email, or something else that represents the stuff-item. The in-trays can be physical, paper-based note taking devices, digital/audio note-taking devices, an digital inbox etc. [1]

Best practices for capturing: At least one in-tray should be available at any time enabling you to free your mind from stuff. You should have as few in-trays as possible to keep an overview, and they should be emptied on a regular basis to ensure that the they do not grow out of proportion and take attention.[1]

Clarify

The clarify step is to empty the in-trays using an item-by-item approach to decide on the actions to be taken and where the item should be placed in your external memory. Each item from the in-trays should go through the decision tree on the Five Steps of Mastering Workflow diagram as described below. [1]

- What is it? For you to recall what the placeholder in your in-tray represents and what it requires of you.

- Is it actionable?

- No: if something should or could be done at a later time you should place it in someday/maybe, if it holds future relevant information you should keep it for reference, else you should discard the item.

- Yes: What is the commitment? Determine the desired outcome of the item. If the outcome cannot be fulfilled by a single action, the item is considered to be a project, and the project should be placed in a project master list along with the outcome.

- What is the next action? Determine the next action, which is the next physical activity to be undertaken in order to move a project closer to the desired outcome or to complete an item.

- Will it take less than two minutes?

- Yes: You should do it right away.

- No: if the next action is more appropriate for someone else to do, you should delegate it and place it on a waiting list. If the action is time specific you should place it in your calendar, and else you should store it on your next actions lists of activities you should do when time allows.

Best practices for clarifying: The next actions should be precise and actionable, such that they are easy to access and do once you have the time. Allen uses the example: if a conference you are going to has been taking your attention and therefore placed in your in-tray, because you have to figure out if Sandra is preparing a press kit, the next action could be ‘E-mail Sandra re: press kits for the conference’. [9]

Organize

In the step of organize you should organize all the items you have stored in clarifying, resulting in a complete system of eight discrete categories as displayed on Five Steps of Mastering Workflow diagram. The eight categories and how they should be used is described below. [1]

- Someday/maybe {hold for review; tickler system}: all items where something should or could be done at a later time should be stored in either a someday/maybe lists, hold for review lists, or a tickler file. Future projects should be placed on a someday/maybe list which should be reviewed on a regular basis, items related to engaging in a specific activity should be stored in hold for review lists (e.g. books to read, restaurants to try), and lastly items you have to be reminded of on a specific time should be placed in a tickler system giving you a reminder on the given time.

- Reference {topic specific; general reference folders}: all information you would like to keep for future reference should be sorted in topic specific folders or in general reference folders for items not belong to a specific topic.

- Trash: everything you do not need to revisit should go into trash.

- Projects master list: all your projects should be placed in a master list, which can be divided into subcategories e.g. house construction projects, projects related to areas of work etc.

- Project plan {and relevant information}: for every project the defined outcome and required actions should be stored in project plans. For each project the project plan and all relevant information should be kept in a separate container.

- Waiting (for someone else to do): a list with all the actions you have delegated and to whom.

- Calendar (to do at a specific time): your calendar should be limited to actions that must be done on the day. This is limited to time specific actions (e.g. appointments), day specific actions to be completed on a specific day but not time (e.g. making a call), and day specific information (e.g. something is due or should be started).

- Next actions (to do as soon as possible): the lists of actions you can do once you have the time. This can be divided into subcategories depending on the context, for example: at workplace, at home, in meeting with (…).

Best practices for organizing: The described elements in the eight categories can be in physical or digital form. The categories should be kept as simple as possible, items should only be stored in one category, and the categories should be reviewed regularly. [1]

Reflect

The reflection step concerns both focusing on specific actions through a daily review and reviewing your external memory through a weekly review:

- The daily review:: of your calendar and next actions lists. Your calendar consists of the things that must get done in the day and therefore constraints the day in regards to availability and time. If your next action lists are categorized by context it should be easy to find the next action to the corresponding context you are in. Once done with an item in your calendar, check when and what the next item is and if it is more appropriate to work on something from a next actions list.[1]

- The weekly review:: of your in-tray, projects, active project plans, next actions, waiting for lists, and someday/maybe list. The items in these categories should be reviewed weekly to obtain a holistic overview and to stay on top of things.[1]

Best practices for reflection: Reflection must be done at specific and consistent intervals as often required in order for everything to stay out of your mind. [1]

Engage

The step of engage concerns making decisions about what to do, what not to do, and how to feel good about both. If all the previous steps in the Five Steps of Mastering Workflow have been fully completed you should be able to use your intuition in this step. There are three models in the methodology you can use to frame your options between actions based on the situation being in the moment, daily work or for reviewing work. [1]

The four criteria model for actions in the moment

In any moment the following three criteria constraints your set of options: (1) the context, (2) the time available, and (3) the energy available. The last criteria in the model is (4) priority. Here you should trust that your intuition will choose the action from the remaining option set that will result in the highest pay-off.[1]

The threefold model for identifying daily work

The model for identifying daily work is based on three kinds of activities: doing predefined work, doing work as it shows up, and defining your work.

- Doing predefined work: from your next actions lists and your calendar.

- Doing work as it shows up: unforeseen or ad-hoc tasks will always appear. You can choose to place them in an in-tray or to take action on them right away. If you choose the latter your intuition has deemed them more important than other tasks in your calendar or next actions lists.

- Defining your work: involves clearing up your in-tray, capturing, organizing, or breaking down projects into actionable steps. [1]

The six-level model for reviewing work

The use of this model should ensure that everything you are engaging with is relevant, and the model should assist you in setting priorities for your decision making between different options of actions. The model is based on the ground level and five horizons as described below.

- Ground level: current actions. The full lists of next actions and your calendar.

- Horizon 1: current projects. Your current projects are generating most of your next actions and items in your calendar.

- Horizon 2: areas of focus and accountabilities. Your interests, roles, and accountabilities will create most of your projects.

- Horizon 3: goals. What you want to achieve in 1 to 2 years from now largely affects your areas of focus and responsibilities.

- Horizon 4: vision. Where you want to be in 3-5 years from now affects both goals, areas of focus, and accountabilities.

- Horizon 5: purpose and principles. Where everything is derived from.

The horizons should not be used as assessment criteria every time you have to choose what projects or actions to engage in. Instead having outlined the horizons and reviewed them will result in a holistic view on your priorities and your intuition will use this to assess your options for actions.[1]

Best practices for engaging: None of the models will give an answer for what to do in the situation, but instead they should assist you in framing your decision, and if all the previous steps in the five step model has been conducted you should be able to trust your intuition in making the appropriate choices. [1]

Implementing and practicing Getting Things Done

The conceptual framework of the Five Steps of Mastering Workflow is rather simple in itself, but leveraging the practice to its full potential requires a complete implementation and examination of the users current commitments and projects regarding both personal and work life. More than half of the book “Getting Things Done – the art of stress-free production” is devoted to a thorough guidance on how to implement and practice each step of the methodology. [1]

As the implementation and practice of the methodology requires a transition for every aspect in life which may not be possible or desired for all the users, Allen has discovered three maturity levels in the practitioners of Getting Things Done:

- The basic: employs the fundamentals of managing workflow

- The graduate: has implemented and integrated total life management system

- The post-graduate: has leveraged skills to empty the mind completely and receives the full benefits

Allen argues that all practitioners either the basic, graduate, post-graduate, or someone who has implemented one trick from the methodology should receive value from it.[1]

Limitations

In Getting Things Done, Allen defines a project by 'Any multistep outcome that can be completed within a year' . [10] . This fits with the Project Management Institute’s (PMI) definition: A project is a temporary endeavor undertaken to create a unique product, service, or result. [11] PMI’s unique product, service or result can be compared to Allen’s outcome, however is PMI’s temporary endeavor not limited to a year. In addition states PMI that Projects drive change and that Projects enable business value creation [12], which is not necessarily the situation for projects by Allen’s definition. His definition includes the individual’s projects as well and could be an everyday project such as cooking a meal which requires several steps; planning the meal, going grocery shopping, and cooking the meal.

The positive effects and theoretical background for Getting Things Done is purely based on Allen’s own and his clients’ experiences. Heylighen and Vidal argued in 2008 that the claims could be theoretically justified based on psychology and cognitive science, but an empirical justification is still outstanding. In their study they also made an extension of the methodology to include collaborative work, but further research on the area is needed for the extension and the collective benefits to be accepted. [13]

The practices for maximizing productivity without stress as offered by Getting things Done are simple, but there lies a great challenge in applying and sustaining the practices. Allen highlights this limitation himself along with a missing expertise and guidance of how to change habits. [14] The practices are based on a less digital work environment with many physical items such as documents, notes, post etc. compared to today, but the practices are none the less still relevant as it is applicable for processing digital information as well and The Five Steps of Mastering Workflow remains the same.

Annotated Bibliography

Allen, D. (2015). Getting Things Done - the art of stress free productivity. London: Piatkus.

The book by David Allen is a comprehensive description of the Getting Things Done practices divided into three parts. The first part: ‘The Art of Getting Things Done’ presents the relevance of the practices in the information age and the two methods: The Five Steps of Mastering Workflow and The Five Phases of Project Planning. The second part: ‘Practicing Stress-Free Productivity’ delivers a thorough description and guidance on how to implement and practice Getting Things Done. The third part: ‘The Power of the Key Principles’ presents the positive outcome related to the practices.

Heylighen and Vidal, C. (2008). Getting Things Done: The Science behind Stress-Free Productivity. Long Range Planning, Volume 41, Issue 6, Pages 585-605.

The article summarizes the practices of Getting Things Done’s Five Steps of Mastering Workflow and review theories of how the human brain processes information and converts the information into actions. The conclusions from the theoretic study is compared to the practices of Getting Things Done arguing that the positive outcome of practicing the Five Steps of Mastering Workflow can be justified theoretically based on psychology and cognitive science. The article also presents an extension of the Getting Things Done practices to use for collaborative work.

Successful by Design (September 6, 2016). Getting Things Done (GTD) by David Allen – Animated Book Summary and Review [YouTube]. Retrieved February 19, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gCswMsONkwY&ab_channel=SuccessfulByDesign.

An animated video of Successful by Design outlining the summary of the horizontal focus and the Five Steps of Mastering Workflow in a simple and visual manner. It briefly touches upon the potential benefits of implementing the practices of Getting Things Done.

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 Allen, D. (2015). Getting Things Done - the art of stress free productivity. London: Piatkus.

- ↑ Successful by Design (September 6, 2016). Getting Things Done (GTD) by David Allen – Animated Book Summary and Review [YouTube channel]. Retrieved February 19, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gCswMsONkwY&ab_channel=SuccessfulByDesign.

- ↑ p.23, Allen, D. (2015). Getting Things Done - the art of stress free productivity. London: Piatkus.

- ↑ p.12, Allen, D. (2015). Getting Things Done - the art of stress free productivity. London: Piatkus.

- ↑ Project Management Institute (PMI). (2017). Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide) (6th Edition).

- ↑ Project Management Institute (PMI). (2017). The Standard for Program Management (4th Edition).

- ↑ Project Management Institute (PMI). (2017). The Standard for Portfolio Management (4th Edition).

- ↑ p.28, Allen, D. (2015). Getting Things Done - the art of stress free productivity. London: Piatkus.

- ↑ p.133, Allen, D. (2015). Getting Things Done - the art of stress free productivity. London: Piatkus.

- ↑ p. 307, Allen, D. (2015). Getting Things Done - the art of stress free productivity. London: Piatkus.

- ↑ p. 4 Project Management Institute (PMI). (2017). Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide) (6th Edition).

- ↑ p. 6, 7 Project Management Institute (PMI). (2017). Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide) (6th Edition).

- ↑ Heylighen and Vidal, C. (2008). Getting Things Done: The Science behind Stress-Free Productivity. Long Range Planning, Volume 41, Issue 6, Pages 585-605.

- ↑ p. xxi, Allen, D. (2015). Getting Things Done - the art of stress free productivity. London: Piatkus.