Complex Project Management (CPM)

Contents |

Abstract

The aim of this article is to introduce practitioners to the concept of Complex Project Management (CPM) and propose tools for analysing project complexity in the early stage of a project and approaches for complex projects. As project become to include international stakeholders and interrelated activities, an increasing concern related to project complexity arises. Identifying sources of complexity turns to be crucial for achieving project's goals. As a matter of fact, complexity influences planning and control phases of a project, jeopardizing the three elements of the Iron Triangle (quality, cost and time). Therefore, it is crucial to define whether a project should be considered complex and why, starting from the early stage of the project life cycle. Introducing an analysis of project complexity in the initiation phase of a project helps project managers defining better goals and objectives, it guides in selecting the right resources, drives the definition of a project structure, and highlights soft spots where to strengthen control. In the last decades, the project management community has developed strategies and tools for spotting and managing complexity. Although a universal consensus on the definition of project complexity has not been yet achieved, this article guides practitioners through two approaches that could be used for managing complex projects.

A bit of background

What is complexity?

While the Cambridge Dictionary define the noun complexity as "the state of having many parts and being difficult to understand or find an answer to", the concept of complexity is still not well defined by the academic community. Depending on the subject of research, different characteristics are identified and chosen to define the complexity of a specific topic. Nevertheless, several general definitions of complexity have been suggested and the researcher considers relevant reporting that one proposed by Sydney Dekker for differentiating Complicated and Complex systems."Complicated systems may be quite intricated and consist of a huge numbers of parts but they can always be taken apart and put together again. Complicated systems become complex when they are opened up to influences that lie way beyond engineering specifications and reliability predictions. Complex systems are held together by local relationships only. Each component is ignorant of the behaviour of the system as a whole and cannot know the full influences of its actions. The boundaries of what constitutes the system become fuzzy; interdependencies and interactions multiply and mushroom" [Dekker et al., 2010]. From this definition it is possible to grasp some knowledge for identifying when we are dealing with a complex project but also which are the main characteristic that we should try to keep in control for avoiding complexity to grow.

The gap

In project contexts, the traditional project management paradigm assumes full pre-given knowledge about the project that is being managed. This, in accordance with the definition given above, is an approach that well fit a complicated project. In contrast to the traditional paradigm, more recent methodologies accept that not all information can be known before to start or in the initial phase of a project, pursuing a learning based approach [Terence et al., 2013]. Therefore, knowledge plays a central role for the definition of complex project. A complex project is characterized by continuously changing shape which requires to redefine goals and scope several times throughout the project life cycle [Terence et al., 2013]. Methodologies such as Agile Methodology tried to address this problem through an iterative approach to projects. Agile project management perfectly fit the life cycle of product development (e.g. software development) since the outcome of one iteration can be accepted or declined, giving birth to a new iteration afterwards [Thomke et al., 1998]. Moreover, this technique address the issue of a changing surrounding environment that can continuously affect project goals' expectations. Nevertheless, this approach does not address the issue of complexity for project which requires a right-first-time outcome. When the goal of a project is to deliver a single outcome, such as the Eurovision Song Contest 2014 in Copenhagen, there is no space for testing and a different approach is required.

The inspiration

This article is inspired by the recent research made on the concept of Complex Project Management, more in details on the material presented during the course Advance Project, Program and Portfolio Management (APPPM) at DTU in the year 2021, an article wrtten by Kathleen B. Hass and Lori B. Lindbergh in 2010 and two scientific paper written by Terence Ahern , Brian Leavy, P.J. Byrne and, Alex Gorod, Leonie Hallo, Tiep Nguyen respectively published in 2013 and 2018. Moreover, it has as reference body the International Centre for Complex Project Management (ICCPM), a not-for-profit organization working to advance knowledge and practice in the management and delivery of complex projects, officially launched in Rome on 10 November 2008 at the 22nd IPMA World Congress on Project Management. The overall goal is to point out which are the common sources of complexity in a project through the APPPM course material and address them to the Project Complexity Model presented by Hass and Lindbergh. Afterwards, the Complex Problem Solving explained by Ahern , Leavy and Byrne is presented and the lack of appropriate power structures for complex project, mentioned in their paper, will be filled by the innovative power structure proposed by Gorod, Hallo and Nguyen. Doing this, the writer aims to enrich the practitioners, interested or involved in complex project, with practical knowledge regarding the strategies and the approach to apply on such projects.

How should I approach a Complex Project?

The sources of project complexity

The first step a practitioner should do for managing complexity is getting to know which are its sources. Projects present several aspects that should be kept in control. For each of these faces, an internal complexity can be identified. All elements belonging to one aspect are related each others and thus they can mutually influence each others. But which are these faces? As reported in the APPPM course material, the typical sources of complexity are:From this list, we can distinguish three groups. The first one is composed of task and time complexities. For these two aspects, different tools have been developed in order to model or map them. It is possible to use Work Breakdown Structure or System mapping for modelling the project's activities or elements, while Gantt chart can be used for defining a timeline. The second group is composed of goal and legal complexities. For this group the approach is mainly strategy based. Prioritizing goals and defining the right contracts require discretionary decisions which cannot be mapped. The decisions are made by the project manager in consensus with project stakeholders in order to satisfy stakeholders' needs. The last group can be defined as an hybrid of the first two. Social and organizational complexities include aspects that can be mapped and others that are driven by strategy. To make an example, social complexity can be model through a Stakeholder map which can be beneficial for identify people, teams, departments or businesses that can affect the project or be affected by it. On the other hand, a human resource strategy needs to be in place for defining who is responsible for what and for managing socio-cultural differences among people involved in the project.

- Technical/Task complexity

- Time complexity

- Goal complexity

- Social complexity

- Organizational complexity

- Legal complexity

This approach to complexity results in a group of tools and strategies aiming to control the whole project. Nevertheless, as previously mentioned, complex projects are characterized by interdependencies across these aspects. Modelling all these relationships would require a substantial amount of resources, and still the output would be an approximation. Practitioners are still suggested to use all relevant tools for mapping their project, even when complex, but they need to be aware that their models will change while the project is running and thus tools and strategy should be seen as alive, in a constant state of mutation.

Project Complexity Model

When are my tools not enough anymore for modelling my project?

The Project Complexity Model has been developed by Kathleen B. Hass and presented for the first time in the book "Managing Project Complexity: A New Model" published in 2009. It has been tested with a quantitative, nonexperimental, descriptive research design on 66 project, programme or portfolio managers from 11 different industries, showing an appreciable level of reliability.

The model consist on a table, where columns identify different level of complexity and rows different project aspects. Three level of complexity are defined: high, medium and low. While, 11 rows identify:For each intersection cell, a series of characteristics are listed so that practitioners can identify which level of complexity each of these areas has for their own projects. Once these attributes are identified, practitioners will use a formula table reporting which are the criteria for defining their project as highly or moderately complex, or a low risk project. The results can be displayed trough a spider-web chart. Doing this, the complexity profile of the project can be visualized and discussed by the team.

- Time/Cost

- Team size

- Team composition and performance

- Urgency and flexibility of cost, time and scope

- Clarity of problem, opportunity and solution

- Requirements/Volatility and risk

- Strategic importance, political implications, multiple stakeholders

- Level of organizational change

- Level of commercial change

- Risk, dependencies and external constraints

- Level of IT complexity

Complex Problem Solving

And so, once I understood my project is complex, which approach should I take?

The complex problem solving is an approach which assumes that not all problem knowledge can be specified in advance. It includes a continues learning process towards the challenge that we are trying to solve. Therefore, in order for this approach to succeed, it is crucial to build a strategy for managing knowledge and learning process.

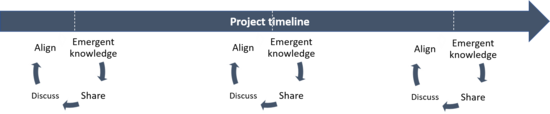

When applied to project, the complex project solving requires project managers to plan a series of learning iterations throughout the project life cycle [Terence et al., 2013]. These learning cycles are focusing on aligning project's goals with the current environment by which the project is surrounded up to that moment. For doing this, the project team analyses what are called emergent knowledge, those not available in the planning phase. These emergent knowledge could arise from several sources such as stakeholders, new legislations, project tasks and a lot more. Sometimes, they could even be known in the planning phase but not considered significant until a trigger event reveal their gravity.

In this scenario of continuously emerging knowledge, Know-how skills should be preferred over plans [Terence et al., 2013]. Know-how knowledge can be described as the knowledge on how to perform or accomplish an activity. The pitfall of such knowledge is their personal dimension. They usually belong to individuals or teams. People that can leave the project while still running, losing so their added value. Nevertheless, know-how can be trained or obtained through sharing and learning cycles. What it is important, it is to create the right atmosphere where people are willing to share their knowledge. Very often this can be challenging since society considers know-how skills as personal assets and people can be reluctant to share them. Therefore, practitioners involved in such projects must focus their knowledge strategy aiming to create distributed learnings.

As mentioned also in Terence Ahern, Brian Leavy and P.J. Byrne research, this knowledge structure requires also to analyse new hierarchy structures. With this project set up, it is important to build the right environment for motivate a common will towards project's goal. For achieving this, the stakeholders should be seen as a community of learners and the project needs to be run by consensus. In the recent years, the concept of network and distributed power have been deeply investigated. In the next paragraph the researcher will present an innovative management approach based on the integration of Network Governance and Command-and-Control methodologies.

Integration of Command-and-Control and Network Governance approaches

The changing nature of complex projects requires to employ a flexible management approach while keeping the right focus on goals. A mixed approach such this one is not available in the management theory. In order to obtain it, practitioners should consider to implement a hierarchy structure which gets characteristics from two well know approaches: Command-and-Control and Network Governance.

Command-and-Control is a managerial approach which requires to coordinate and oversee workers' performance to assure their tasks will be completed. This approach is commonly top-down, where people on the upper-next hierarchy level give orders to those below. Although it can be an optimal approach for project that can be fully planned, it lacks flexibility in a changing environment.

Network Governance, instead, allows a great level of freedom among different project's stakeholders. It is a quite recent approach that is trying to fill the gap of democratic organizational and project structures. This approach can be seen as a network where dots are linked each other and has almost the same weight. In this way, different teams working in a project are allows to take their own decision and influencing project's outcomes. People on a higher hierarchy level influence those below through directions, not orders, nudging teams towards the right direction. Although its democratic nature can sound beautiful, the lack of control can jeopardize efficiency and effectiveness.

Both approaches have their weak and strong points but a merged approach could benefit from both of them. Project managers should define the goals to pursue, which should be shared and commonly defined by all stakeholders, hypothetically in a workshop or meeting. After that, each teams should be free to follow its own path towards its goals. While building their strategy, teams are suggested to interact each others in order to align themselves. Reoccurring meeting should be planned for sharing learnings and build that structure of distributed knowledge mentioned above. These meeting should also be used by the project manager for understanding if some teams are not going in the right directions, nudging them afterwards. In this mixed approach, managers still detain the ability of imposing a specific directions even if this approach should be avoided as much as possible. The final structure should be a project environment where stakeholders take their own decisions towards shared goals and people on high hierarchy level can take action in case of severe misalignment.

Limitations

Although a mixed Command-and-Control and Governance approach can fit complicated and complex project, it is not beneficial for not complex project. As a matter of fact, if it is possible to plan and map the project, it make more sense to use a system oriented approach which allows an higher level of control. While practitioners should analyse their project complexity and are suggested to estimate if their project is complex or not through the Project Complexity Model, using the Complex Problem Solving and the integrated approach is suggested only when a project turns out to be complex.

The pitfall of the Complex Problem Solving are the unknown-known knowledge. Important information ,known by teams or stakeholders, which are not consider relevant from the owner. For this reason, the risk is that these knowledges are not shared. Moreover, creating the right environment for knowledge sharing can be very challenging. It is important to create the right synergy among stakeholders, so that knowledge owners are willing to share them.

Regarding the Integrated Command-and-Control and Network Governance approach, it is relevant to point out its still lack of control. Mangers should trust their subordinates and let them taking the decisions. This can work for several project managers but be very hard to apply for others. Furthermore, managers should be aware of how much control they are exerting upon their subordinates in order to avoid to jeopardize their freedom of choice.

These approaches are inspired by relatively recent papers. Although their innovative approaches can inspire practitioners, they still need to be further investigate for proving the goodness in every industry.

Bibliography

Dekker, Sidney & Cilliers, Paul & Hofmeyr, Jan-Hendrik. (2011). The complexity of failure: Implications of complexity theory for safety investigations. Safety Science. 49. 939-945. 10.1016/j.ssci.2011.01.008.

Thomke, S., & Reinertsen, D. (1998). Agile Product Development: MANAGING DEVELOPMENT FLEXIBILITY IN UNCERTAIN ENVIRONMENTS. California Management Review, 41(1), 8–30. https://doi.org/10.2307/41165973

Ahern, Terence & Leavy, Brian & Byrne, P.. (2014). Complex project management as complex problem solving: A distributed knowledge management perspective. International Journal of Project Management. 32. 1371-1381. 10.1016/j.ijproman.2013.06.007.

Hass, K. B. & Lindbergh, L. B. (2010). The bottom line on project complexity: applying a new complexity model. Paper presented at PMI® Global Congress 2010—North America, Washington, DC. Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute.

Gorod, Alex & Hallo, Leonie & Nguyen, Tiep. (2018). A Systemic Approach to Complex Project Management: Integration of Command‐and‐Control and Network Governance. Systems Research and Behavioral Science. 35. 10.1002/sres.2520.

Hass, K.B. (2009), Managing Project Complexity: A New Model. Vienna, VA: Management Concepts