Effects of Social Loafing on Team Performance

Written by Nils Lehmann

Abstract

Working in groups and teams is a commonly known state of the art form of collaboration, not only in businesses but in all kinds of educational systems, governmental organizations and many more [1]. But is working in teams and groups more efficient than working individually?

After Maximilien Ringelmann's 1913 studies on efficiency of humans in groups, which are the basis for the so-called social loafing effect, one can question this collaborative working approach [2]. The Social loafing effect explains the phenomenon that the motivation of individuals in teams (especially when exceeding 3 members) can be lower compared to the motivation while performing individual tasks [3]. Moreover, this is linked and valid for the performance and efforts put into work. Social loafing is well studied and over and over validated [4]. Social loafing describes therefore the decline in performance of individuals when working in groups and is the opposite of social facilitation (an increased performance when doing tasks while being watched by others) [3].

Contents |

The Phenomenon of Social Loafing

Social loafing as a phenomenon can be described or defined as "...the reduction in motivation and effort when individuals’ work collectively compared with when they work individually or coactively" [6]. Social loafing was first discovered back in the early 1900's and since then is a quite known effect, which was validated in more than hundred studies of explaining performance losses in group or teamwork. Furthermore, it is a phenomenon which occurs while performing physical, work-related, or cognitive tasks[6].

But why does social loafing occur when working in groups?

To answer this question a large number of studies were carried out, as well as theories were created to explain this effect. All those studies and theories are concluding that social loafing, directly or indirectly, is always related to the motivation of the individual, besides other variables, and the circumstances in which the group work take place.

Factors Influencing Social Loafing

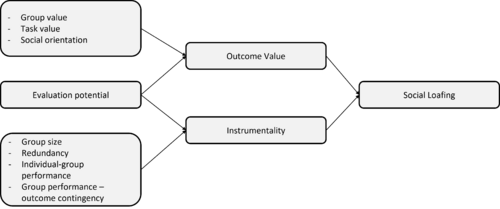

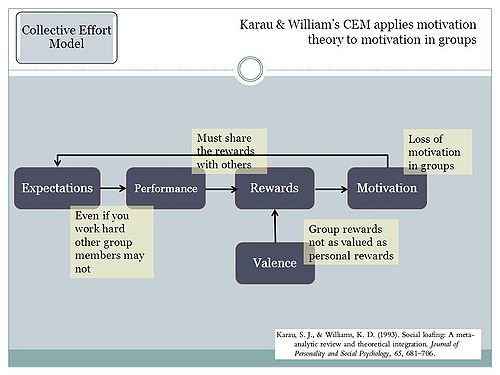

To understand the results of the studies and the variables influencing social loafing, one first needs to bear in mind that theories on motivation for individual tasks are transferred to be valid in group tasks, such as Vroom's expectancy-value theory [7]. Due to Vroom (1964) motivation is based on three factors:[1]

- Expectancy - expectancy that effort will lead to performance (e.g., input of more working hours will lead to better performance)

- Instrumentality - performance will lead to an outcome (e.g., believe that chances are high to win a price → high instrumentality)

- Value - extend to which an outcome is valued (e.g., the self-perceived value of the performance of a task itself)

In order to better understand the relationship between value, expectancy, and motivation of individuals it is helpful to introduce the collective effort model (CEM) by Karau and Williams (1993) [8]. This model basically states that group members’ motivation will decline when working on collective tasks because their expectation of a successful goal achievement is lower and so the value of the group goal diminishes [6] [3]. It is based on assumption that "motivation for an outcome depends on the significance of that outcome and the probability of achieving it" [9].

Instrumentality

When it comes to instrumentality on individual tasks it is all about the relation between individual performance and individual outcome [1]. This means a person can easier determine how much effort needs to be inputted to receive a certain level of output. For collective tasks this relation seems to be way more complicated. Since a team consists of several members the instrumentality for a person looks different. It consists of the following individually perceived relationships between:[1]

- Individual and group performance

- Group performance and group outcome

- Group outcome and individual outcome

Simply spoken individuals will exert effort if they expect this will lead to valuable outcomes within the group task. For an individual to put in that effort, it has to be valuable to them with desirable (individual) results. This is achieved, if:[1]

- Individual effort leads to individual performance

- Individual performance is related to group performance (one's contribution is valuable for the group)

- Group performance leads to a valued group outcome (the group's outcome is perceived valuable for the individuals and the group)

- Group outcome is related to a valued individual outcome (the group outcome is perceived as worthy and desirable for oneself)

If the relationships mentioned above are not valid, an individual will not put in the necessary effort within a group task. In the next section the influence of performance evaluation and perceived value of work is further outlined. These are very important determinants which are directly linked to the three factors influencing social loafing.

Based on the instrumentality factors can be identified which are directly linked to the motivation and effort-input of individuals in groups. The factors influencing instrumentality are:[1] [3]

- Group Size: Social loafing will less likely occur in smaller teams

- Redundancy: The contribution of a unique task within the group will lead to lower social loafing of an individual because they perceive their work as important to achieve the group's goals (non-redundancy tasks)

- Individual-Group performance contingency: If individuals perceive a group goal achievement as possible, they will exert more effort [10]

- Group performance-outcome contingency: Group members will exert more effort if they perceive the goal achievement as possible [10]

Value of Work and Evaluation Potentials

To ensure that group members do not fall into social loafing, there are a number of factors that influence people's intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, and thus the likelihood that these people will perform to their full potential despite group work. Such factors are:[1] [3] [8]

- Task Value: Individuals will loaf less when the task itself is perceived worth doing (intrinsic motivation, related to the Dispensability of Effort[8])

- Group Value: Strong group identity reduces social loafing because contributing to the group in itself is perceived valuable

- Individual Evaluation: Individuals will loaf less if their individual performance can be measured, this increases the instrumentality and prevents individuals from "hiding" within the group

- Expectations of Others: Individuals will loaf less if they expect other group members to perform bad

Finally, Figure 2 graphically depicts the relationships between the different factors and determinants of social loafing.

Equity of Work

As stated above the expectations of others performance has an influence on an individual's performance. Rutte (2008) puts forward the thesis that this is due to the fact that performance is always evaluated relatively compared to others[1]. Furthermore, she states that an individual will compare oneself with others who are similar to oneself[1]. This could be the reason why an individual exerts more effort within a group work when she thinks other team members will perform badly. But this urge for comparison is taken up in the literature by Adams (1965), among others[11]. He concludes that people do not only compare their results, but also what they invest in the work (their inputs)[1] [11]. As of Adams (1965) "people strive for equity: the ratio of their own inputs and outcomes should be equal to the ratio of inputs and outcomes of others" (Rutte (2008), P. 369)[1][11]. Based on the strive for equity, two important effects related to social loafing can be introduced: the "free rider" and "sucker" effect.

Free Riding and Sucker Effect

"Free riders" are group members, who profit from the contributions of the other team members, in order to achieve the group's goal, without delivering their fair and appropriate part of work [3]. On the other side "suckers" are the team members who need to work harder in order to equalize the missing contributions of free riders. Thus, a potential "sucker" will reduce his amount of effort in the group work in order not to be the "sucker" [3]. As a consequence, the whole group performance can suffer, and the effect of social loafing can be amplified. This will lead to a prisoner’s dilemma which is perfectly described by Rutte (2008, Page 370): "for each group member it is more rational to defect (i.e., not to contribute) than to cooperate (i.e., to contribute); however, if all group members defect, they are all worse off than if all had cooperated" [1]. Because of the fact that high performance members need to put in less effort for the same performance and they try to avoid being the sucker, they will probably put in less effort if they expect others to perform badly in order to restore a fair situation [1]. As a consequence, overall group performance may suffer. To prevent this, there are some effective ways to counteract social loafing.

Critical Review on Social Loafing and Lessons for the Practice

Looking at the environment of the studies, one will note that studies showing increased social loafing were tested in laboratory settings rather than in organizations [1]. As a rule, randomly assembled groups are used to perform simple tasks (e.g., rope pulling). It is obvious that these groups will perform even worse compared to groups in organizational context which is also shown in Karau and Williams (1993) review on social loafing studies [6] [8]. This doesn't mean, that social loafing is not applicable in organizational context, but its extent is to a smaller degree compared to laboratory studies [8]. After the factors influencing social loafing were presented, one may question the implications for project managers. To tackle social loafing in projects, recommendations for possible solutions are presented:[1] [3] [8]Value of Outcome

The value of outcome is the most influential factor on social loafing. The value factor can be split into different categories, such as the task value, group value, and outcome value (see below). In general, for individuals, the outcome value must be measurable and desirable. Therefore, a project manager is asked to find solutions in order to evaluate and reward the individual tasks (see below). Furthermore, the project manager should create an environment so that the overall project goal and its project steps are valuable for the organization and the group members, in terms that the project will bring value to the organization but also to the individuals. As Karau and Wilhau (2019, Page 20) states: "individuals will only work hard when they view their individual efforts as likely to lead to consequences that they personally value"[8]. This is reflected in the results of the meta-analysis where high task meaningfulness leads to the disappearance of social loafing [6].

→ As project manager the first task is to create a desirable goal, defining a system which allows (individual) rewards and assigned meaningful/relevant tasks to group members.

Evaluation and Rewards

A project manager should reward effort and contribution. But this brings with it the assumption, that individual performance is easily measurable in group tasks, which in practice, is very difficult. It is indeed an obstacle in order to prevent social loafing. Measuring individual performance may sound easy, but it is anything but that. This becomes clear when groups perform creative tasks. Here, a project manager might find it difficult to determine the individual results, for example during brainstorming. It is also questionable whether this would be desirable in that case or whether it would have a negative impact on the generation of ideas. But nevertheless, project managers should try to measure and evaluate individual performance. If this is the case an individual will put in more effort because there is no hiding behind other group members. In order to reward the (individual) contributions the project manager can make use of the different types of rewards:[13] [1]

- External Individual Rewards: can be financial or social incentives (individual performance needs to be measurable!)

- Internal Individual Rewards: value creating based on purely performing the task (e.g., achieving a certain level of standard, meaningful task for the individual)

- External Collective Rewards: creating collective financial or social incentives (e.g., group bonuses)

- Internal Collective Rewards: value creating for group based on working on a meaningful goal or individuals feel proud and obligated towards the group

The challenge for project managers in regard to individual rewards is definitely the possibility of measuring performance or contributions individually. If it is not possible for a project manager to measure individual performance the project manager should think of proper collective rewards. Nevertheless, even these results should best be linked to individual rewards.

→ Evaluate and reward individual performance as well as group performance in order to manage the effort inputs of group members.

Task Value

As a learning from all the studies on social loafing there are some important elements in regard to the task itself. The main findings are related to the uniqueness of the task, as well as the attractiveness and meaning of a task. Furthermore, for a group member to exert as much effort as possible her own task or contribution needs to be indispensable or unique. The following overview names certain parameters of the task which influence the level of loafing: [3] [8]

- Dispensability of Effort: The task of each team member should be an elementary part on the way to achieving the group goal. It should be clearly shown to the individual what influence her task has on the overall project.

- Meaning and Uniqueness: Each task should have a meaning in the bigger project picture, but also for the individual itself. Moreover, a project manager should avoid giving redundant tasks. Team members will loaf less if their task is of meaning and unique compared to the other tasks.

- Personal Involvement: To achieve meaningful and unique tasks for each individual member, a project manager should involve all group members in the task creation process. If people are involved in this process, they have a greater feeling of meaning and belonging not only to the task but also to the group.

- Evaluation and Incentives: Evaluation of the individual tasks will reinforce commitment. Therefore, project managers should install mechanisms for feedback (also from other group members) and incentivize contribution in the group tasks.

- Redundancy: The project manager should define unique tasks in order for group members to see their contribution as valuable.

Setting unique tasks in a project context can be relatively easy when it comes to new or custom-made projects. Also showing the necessity of one's individual task and thus creating task meaning can be handled by the project manager. When it comes to larger or very complex projects for example the inclusion of team members for task creating can be helpful to gather the whole scope. But more standardized projects with a lot of repetitive tasks may be a challenge for project managers to create uniqueness in tasks. Therefore, in practice it is often way harder to create task value for all single project elements. A project manager needs than to handle a situation where people tend to loaf because of redundant or repetitive tasks (e.g., monthly reporting of KPI's or documentation of process steps).

→ Project Managers should create unique tasks and point out the contribution a task will have for the achievement of the overall project goal. Furthermore, the project manager should openly point out the necessity of some repetitive tasks and what the expectance of performing them is.

Group

In order to deliver the desired performance, there are factors in regard to the group itself which influence the degree to which social loafing is practiced:

- Value: As previously stated, a clear output value of the task increases exerted efforts. Therefore, project managers are asked to create meaningful tasks and attach a valuable result to the fulfillment. This can be done either by rewarding (see evaluation) or through connecting the specific task with an overall wishful future state. This is a powerful factor influencing social loafing, because group members will compare and evaluate the overall value and performance with objective performance standards or group performance level (e.g., via public feedback)[8] and thus evaluating if it is worth participating at a group task.

- Size: The group size has an enormous influence on social loafing. Already Ringelmann (1913) discovered the effect of group size in regard to individual effort and performance. As a rule of thumb, a project manager should keep a group or team as small as possible. It would be recommendable to split bigger teams into several sub-teams in order not to step into the trap of social loafing.

- Cohesiveness: Another important aspect is the cohesion of a group. The studies mentioned above all discovered that social loafing occurs less if the group members have trustful relationships (e.g., friends). So, in order to boost team performance, project managers should invest time and effort in building group trust and cohesion. This will lead to an identification with the group and therefore an increased willingness to bring in effort and performance.

→ Project managers should keep small groups and invest in group forming as well as building cohesiveness within the group through social activities (outside of work). This is especially important in new formed teams.

Expectancy and Equity

After all it is also relevant for the project manager to develop situations which create the expectation, that effort is necessary to achieve results. This draws the circle back to the instrumentality of the group members. Only when they are expecting (and expected) to exert effort to reach a certain (valuable) goal, they will exert the necessary effort. But a project manager should also bear in mind, that different group members have different individual goals and instrumentality within a specific project or task. Thus, the project manager should openly communicate that, under certain conditions, it is legitimate that the performance of individuals differentiate (e.g., one performs better than the other). It is important to tackle the feeling of equity in group works. Nevertheless, this should go side by side with individual performance measurement and rewarding in order not to demotivate the better performing group members.

→ Project managers should discuss the expectancy of each single group member as well as the project output at the beginning of a project.

Summary of the Implications for Project Managers

Organization of Projects

There are some recommendations for the organization of projects, teams, and groups in general. These criteria’s sum up some of the above-mentioned points and ideas:[3]

- Select group members in accordance with their skills and the tasks required, e.g., group members who already have a relationship, select unique skilled employees

- Set goals that are both challenging and realistic, e.g., in accordance with a company’s vision (valuable outcome)

- Provide and establish nonevaluative conditions to test and use skills e.g., non-evaluating feedback environment or test benches

- Provide regular feedback on task performance, e.g., through management feedback or peer feedback

- Provide the necessary resources and support actions, e.g., qualifications or space environment

- Establish an incentive system in accordance with the findings above, e.g., define standards or comparative criteria

Organization of Teams and Reward Systems

Project Managers should:

→ create a desirable goal, defining a system which allows (individual) rewards and assigned meaningful/relevant tasks to group members.

→ evaluate and reward individual performance as well as group performance in order to manage the effort inputs of group members.

→ create unique tasks, point out their contribution to the achievement of the overall project goal, and openly point out the necessity of repetitive tasks and the expectance of performing them.

→ keep small groups and invest in group forming as well as building cohesiveness within the group through social activities. This is especially important in new formed teams.

→ discuss the expectancy of each single group member as well as the project output at the beginning of a project.

→ be aware of the recommendations for setting up a organization.

Annotated Bibliography

- Ingham, A. G., et. al (1974). The Ringelmann effect: Studies of group size and group performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 10, 371–384.

- Ingham's studies in 1974 were the first laboratory field study after Ringelmann explored social loafing in his experiments in the early 1900's. Ingham and his colleagues studied the effect of group size on the individual’s motivation, as well as several factors influencing the motivation of the persons participating in the studies. These studies gave new insights on social loafing and are therefore a fundamental part of studying social loafing [4].

- Karau, S. J., & Williams, K. D. (1993).Social loafing: A meta-analytic review and theoretical integration. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65, 681–706.

- In this Journal article Karau and Wilhau outlinin the classical theories and try to give reasons for social loafing. They go very deep into the psychological theories explaining this phenomenon. They go in detail when it comes to factors reducing social loafing and trying to take this into the group contact. They present the challenge of applying theories and concepts based on individual motivation to groups. In their last section they also explain possible theories to gain motivation within groups [6].

- Rutte, C. G. (2008). Social Loafing in Teams. In International Handbook of Organizational Teamwork and Cooperative Working, pp. 361-378.

- In her chapter about social loafing Rutte has a close look at existing theories of why social loafing happens. She discussed two contrary viewpoints and highlight their strengths and weaknesses. Furthermore, she also criticized that most of the studies about social loafing were done in laboratory environments. She then states that research in an organizational context does not come to the same conclusions. Social loafing is detected rarely in the organizational world. She critically discusses those viewpoints and gives the reader a good overview of the controversies of this subject [1].

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 Rutte, C. G. (2008). Social Loafing in Teams. In International Handbook of Organizational Teamwork and Cooperative Working, pp. 361-378. https://onlinelibrary-wiley-com.proxy.findit.cvt.dk/doi/10.1002/9780470696712.ch17

- ↑ Ringelmann, M. (1913). Recherches sur les moteurs anim´es: travail de l’homme. Annales de l’Institut National Agronomique, 2(12), 1–40. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k54409695/f15.item.langEN

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 3.9 Gil, F. (2004). Social Loafing. In Encyclopedia of Applied Psychology, Three-volume Set, pp. 411-419. https://www-sciencedirect-com.proxy.findit.cvt.dk/science/article/pii/B0126574103000945

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Ingham, A. G., Levinger, G., Graves, J., & Peckham, V. (1974). The Ringelmann effect: Studies of group size and group performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 10, 371–384. https://www-sciencedirect-com.proxy.findit.cvt.dk/science/article/pii/002210317490033X

- ↑ VIVIFYCHANGECATALYST (2014). https://vivifychangecatalyst.files.wordpress.com/2014/02/social-loafing1.jpg. 23 February 2014

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 Karau, S. J., & Williams, K. D. (1993). Social loafing: A meta-analytic review and theoretical integration. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65, 681–706. https://doi.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2F0022-3514.65.4.681

- ↑ Vroom, V. H. (1964). Work and Motivation. New York: Wiley. https://www.wiley.com/en-us/Work+and+Motivation-p-9780787900304

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 8.7 8.8 Karau, S. J. and Wilhau, A. J. (2019). Social loafing and motivation gains in groups: An integrative review, In Individual Motivation Within Groups: Social Loafing and Motivation Gains in Work, Academic, and Sports Teams, pp. 3-51. https://www-sciencedirect-com.proxy.findit.cvt.dk/book/9780128498675/individual-motivation-within-groups

- ↑ American Psychological Association. expectancy-value model .Dictionary of Psychology. 20.02.2022. https://dictionary.apa.org/expectancy-value-model

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Shepperd, J. A. & Taylor, K. M. (1999). Social loafing and expectancy-value theory. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 25(9), 1147–1158. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/01461672992512008

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Adams, J. S. (1965). Inequity in social exchange. In L. Berkowitz (ed.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (Vol. 2). New York: Academic Press. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0065260108601082

- ↑ Hofmann, R. (2020). Social Loafing: Definition, Examples and Theory. Simply Psychology. 22.07.2020. https://www.simplypsychology.org/social-loafing.html

- ↑ Shepperd, J. A. (1993). Productivity loss in performance groups: a motivation analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 113, 67–81. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1993-17468-001