Myers-Briggs Type Indicator

Developed by Birthe Wohlenberg

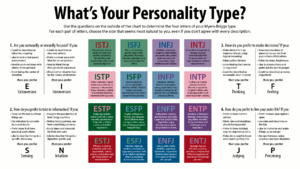

The Myers-Brigs Type Indicator® (MBTI) is an instrument designed to map psychological personality types, in order to understand group dynamics and better manage e.g. project groups. There are 16 different MBTI® personality types indicated by a four-letter abbreviation representing the preference of the person within each of the four dichotomies; introversion (I)/extraversion (E), sensing (S)/intuition (N), thinking (T)/feeling (F), and judging (J)/perceiving (P).

The MBTI® is widely used to give personal and professional insights to the individual, in education, coaching, therapy etc. Many companies use personality type tests when hiring new employees to increase the chances of good group dynamics with the existing team of employees.[1]

The MBTI® is as widely disputed as it is popular. According to the Myers-Briggs Foundation the MBTI® is the most applied personality test in the world and both valid and reliable, however various critics claim the exact opposite.

Contents |

MBTI Basics

Understanding human behaviour is key to understanding group dynamics and is therefore vital in projects and the management of these. The Myers-Brigs Type Indicator® (MBTI) is an instrument designed to map psychological personality types. The MBTI® is a questionnaire that indicates a person’s preferences within four dichotomies, i.e. opposite preferences on a continuous scale, in how people perceive the world and make decisions. There are two pairs of psychological functions.

- Sensing/intuition: The irrational information gathering (way of perceiving)

- Thinking/feeling: The rational decision-making (way of judging)

These two pairs plus the perceiving/judging functions make up three of the four dichotomies. The forth is the attitude towards the surrounding world; extraversion or introversion. MBTI® describes 16 different personality types according to the two outcomes in each of the four dichotomies; introversion (I)/extraversion (E), sensing (S)/intuition (N), thinking (T)/feeling (F), and judging (J)/perceiving (P). A given personality type is indicated by a four-letter abbreviation representing the preference of the person within each pair, e.g. ENTJ (Extraverted thinking with introverted intuition), INFP (Introverted feeling with extraverted intuition) etc.

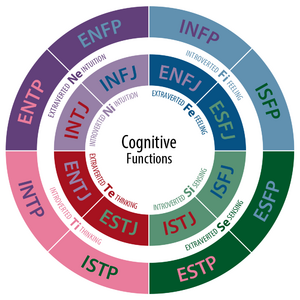

Type dynamics

Every type will have a dominant psychological function, an auxiliary function supporting and balancing the dominant, a tertiary, and lastly a forth inferior function which the surrounding world hardly ever sees. The inferior function usually only comes to show if/when the person is under pressure in a highly stressed situation. The dominant function is indicated by the preferred lifestyle structure, judging (J) or perceiving (P). For extraverts, the dominant function is the preferred judging or perceiving function. For an ESTJ type, the J determines that the dominant function will be extraverted thinking (Te), for an ESTP type it will be extraverted sensing (Se)). The auxiliary function is the other psychological function. The attitude of the auxiliary function is opposite of the dominant function, so for an ESTJ type, the axillary function will be introverted sensing (Se), for an ESTP type it will be introverted thinking (Ti)).

For introverts, the preferred judging or perceiving function indicates the auxiliary function. As for extraverts, the attitude of the auxiliary function is opposite, i.e. extraverted. For an ISTJ type, the dominant function is introverted sensing (Si) and the auxiliary function is extraverted thinking (Te). The dominant and auxiliary functions are called the function pair.

The attitude of a person towards the surrounding world (extraversion or introversion) has a substantial influence on the function pair. Each function can be expressed in either the inner world or the outer world, and the same function can look very different depending on the attitude of the person. The following examples are from The Myers & Briggs Foundation[2]

Extraverted Sensing: Acts on concrete data from here and now. Trusts the present, then lets it go.

Introverted Sensing: Compares present facts and experiences to past experience. Trusts the past. Stores sensory data for future use.

Extraverted Intuition: Sees possibilities in the external world. Trusts flashes from the unconscious, which can then be shared with others.

Introverted Intuition: Looks at consistency of ideas and thoughts with an internal framework. Trusts flashes from the unconscious, which may be hard for others to understand.

Extraverted Thinking: Seeks logic and consistency in the outside world. Concern for external laws and rules.

Introverted Thinking: Seeks internal consistency and logic of ideas. Trusts his or her internal framework, which may be difficult to explain to others.

Extraverted Feeling: Seeks harmony with and between people in the outside world. Interpersonal and cultural values are important.

Introverted Feeling: Seeks harmony of action and thoughts with personal values. May not always articulate those values.

Application

"When people differ, a knowledge of type lessens friction and eases strain. In addition it reveals the value of differences. No one has to be good at everything." Isabel Briggs Myers[2]

According to The Myers & Briggs Foundation, knowing and understanding your own (and others’) type can provide insights that are valuable in many types of situations and relationships. These include work related issues like career choice and change, collaboration with colleagues, and management of your own work. It also includes personal matters such as personal growth and relationships with friend, partners and children. Insight to types can prove valuable in learning environments, e.g. by knowing how you learn best and different teaching methods according to the types of those you teach.

The MBTI® is widely used all over the world, and is probably the most used personality assessment. Millions of people asses their personality every year. [3] Ethical guidelines are provided by the Myers-Briggs Foundation to ensure an ethical use of the MBTI® and avoid abuse, including "using type to assess people's abilities and using type to pressure people toward certain behaviours".[2] Becoming MBTI® certified is required to administer the instrument to others. A certified practitioner is trained in the use and interpretation of the MBTI® to be able to help clients understand the results of the questionnaire and how to use these results actively in their professional and personal lives.

Some practitioners point to how different types will be particularly good at certain types of job, and feel satisfied because the job caters to the preferences of the type. An example of this is ISTJs as accountants or surgeons “because they are very good at focusing on detail and order, and like quiet time to think and process information”.[4] Knowledge on type can thus be used for career choices but also when hiring new employees. This however, is against the ethical use guidelines of the Myers & Briggs Foundation.[2] Another way to utilise the IMBT® is within project teams. Knowing how each individual prefers to work can help the planning of different tasks. The team behind the British website “Skills You Need” gives the following example: “If you’re part of a small project team, you can use MBTI to work out how each individual will prefer to work, and allocate the work accordingly. Used alongside Belbin’s team roles it can be a useful way of playing to people’s strengths. For example, ENFPs tend to be good at gathering information from people. They’ll pull together a potentially vast amount of interview information without making any judgements about it as they go along. Unlike a J-type, they won’t discard information that doesn’t support a hypothesis. S-P-types will be good at research from books and online. And once the information is gathered, J-types can then pull together the analysis and shut down some of the possible options, tempered by the need of the P-types to keep gathering more information. N-Js will look at possibilities; S-Js will just look at what is there.It can be difficult for P-types and J-types to work well together in a team because of their timing preferences (last minute vs steady work). If they can manage it, however, it makes for a stronger team because there is focus on both gathering lots of data, and shutting down the data collection and drawing conclusions.” [4]

Limitations

The MBTI® is as widely disputed as it is popular. According to the Myers-Briggs Foundation the MBTI® is both valid and reliable, however various critics claim the exact opposite. The main point of critique is that there is not scientific proof for the theory. The MBTI® is based on a theory developed in 1921 by Carl Jung, in his book “Psychological Type”. Jung’s work was based on his observations and he used anecdotes to support his theories, not controlled scientific studies, as is the norm today.

One of the major issues with the MBTI® is its statistical structure. As with other data, we would expect any given sample to have a normal distribution over the parameter measured. According to the MBTI® an ESTJ type is quite different from an ISTJ. We would expect that since people are either extraverted or introverted, we would see a normal distribution over the two preferences. However, what we see is a normal distribution over the dichotomy. [5] The majority of people are ambiverts, meaning neither introverted nor extraverted, but somewhere in between.[3] Only 30% will be in the extreme ends of the scales, and thereby the complexcity of 70% of the population is not accounted for. Robbrecht van Amerongen calls the MBTI® “a good list of stereotypes presented to you as a very complicated fortune cookie.” [1] This means that there is likely very little difference between the test results of an extravert and an introvert, e.g. an ESTJ and an ISTJ. The dominant function of the ESTJ is extraverted thinking (Te) where the dominant function of the ISTJ is introverted intuition (Ni). Because of the 16 rigid types it is possible that people with similar scores in the questionnaire could be “labelled” with very different personality types.

Another scientific issue is the reliability of the MBTI®. The primary method for assessing reliability is the test-retest reliability, where the same ‘experiment’ is performed twice with an interval of anything from a few weeks to more than a year. A high reliability will give the same result on both occasions. With the MBTI® however, multiple studies show that up to 50% will be a different type, even with a test-retest interval of only 5 weeks.[3] Besides a rather low reliability, the standard error of measure is relatively large.[5] Because of the way the MBTI® is scored, the standard error of measure is not taken into account. David J. Pittenger makes the following statement: “(…) there are cutoff points that divide the dimensions. When the score is above the cutoff, one classification is given; if the score is below the cutoff, the opposite classification is given. Although some users of the MBTI try to interpret how close the score is to the cutoff, this practice is inconsistent with the theory of the MBTI.”[5]

The validity of the MBTI® is also disputed amongst critics of the instrument. Validity is difficult to assess since it evaluates how well a test measures what it is supposed to measure. To conclude whether a test is valid, it must be proven that the results of the test is independent of the test subjects’ level of education, gender, age, culture, etc. Furthermore, it must be shown “that there is a consistent and meaningful relation between MBTI® results and success in career placement”[5]. There are many ways to evaluate the validity of any test.

A statistic procedure is the Factor Analysis. In the case of MBTI® the analysis would determine whether the four dichotomies of the theory exists in reality. The analysis should show four “factors” (or clusters) of questions, each independent from the others. If factors are overlapping, it probably means they are measuring the same thing. Research has shown anything from six different factors, high measurement errors, and that JP and SN dichotomies are interdependent.[5] In conclusion, the theory behind the MBTI® does not have any statistical data to support it, which is normally a ‘must’ in the scientifically based world of today. Adam Grant calls the MBTI “A Physical Exam That Ignores Your Torso and One of Your Arms.”[3]

Many claim that certain types will be more satisfied in certain job types. This is the basis of MBTI as a career counselling tool. However, there is no data to support these claims. [3] Looking at the statistics of types in specific occupations, there is a high correlation between the percentages of types in the specific jobs and the general population. When the correlation deviates, it is usually because the profession is dominated by either men or women. The distribution of types then correlates with the distribution among the particular gender.

There is continuous dispute whether the MBTI® measures anything of value. If the theory behind is invalid, then the assessment based on this theory is impractical and really has no use. Edythe Richards states that “indeed, people are complex, changeable, and unpredictable. The MBTI® cannot adequately measure every facet of one’s personality, however, neither can any other “test”.” [6] If the MBTI® is only half the truth, then one might ask – what is it good for then?

Adam Grant points to an alternative personality type assessment called the Big Five personality trait. This theory meets the standard of scientific testing, and have shown a high reliability and “considerable power in predicting job performance and team effectiveness” [3] Multiple sceptics of the MBTI® advocates for the use of Big Five, and continue to point to the flaws and deficiencies of the MBTI®. [5] [7] [1]

Grant makes this final comment: “MBTI, I’m breaking up with you. It’s not me. It’s you. (…) If You Want Me Back, You Need to Change Too. (…) If not, we are never, ever, ever getting back together.” [3] [7]

Annotated Bibliography

The Myers-Briggs Foundation, 2016, http://www.myersbriggs.org

The official website of the MBTI® instrument. The history of the development of the theory behind the MBTI. What the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator® instrument is and what it measures. Information on the sixteen types, the eight preferences and other tools for a basic understanding of personality type. Guidance for the appropriate and ethical use of the instrument and what is expected from certified administrators.

Pittenger, David J. (November 1993). “Measuring the MBTI... And Coming Up Short”. http://www.indiana.edu/~jobtalk/HRMWebsite/hrm/articles/develop/mbti.pdf. Journal of Career Planning and Employment. 54 (1): 48–52.

A review of the basic research that questions the validity of the MBTI. There is a large body of research that suggests that the claims made about the MBTI cannot be supported. It appears that the MBTI does not conform to many of the basic standards expected of psychological tests, such as its statistical structure, its reliability, and its validity. The popularity of the instrument is interpreted as an indication of its accuracy and utility, and the MBTI has become a popular instrument for reasons unrelated to its reliability and validity.

Richards, Edythe. (2014). “Myers-Briggs® Myths and Misuse – MBTI® remains a useful tool”. http://atopcareer.com/myers-briggs-myths-and-misuse/

Atop Career is a blog for Mid-Life Career Changers. Edythe Richards is a career counsellor, Myers-Briggs® Master Practitioner, and Certified Emotional Intelligence (EQ-i 2.0/EQ-I 360) Administrator based in the Washington, DC Metro area. In this article, she discusses why users can continue to rely on the MBTI® as a measure of psychological type, as well as appropriate use and limitations of the instrument. In the article, she addresses the five most criticised areas from a practitioner’s standpoint, as well as the limitations of the assessment. The five areas are the questionable origin of the theory, the lack of scientific credibility, the binary choices, the questionable results, and the relation to the real world.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 van Amerongen, Robbrecht. (2015) “Myers-Briggs Test (MBTI) is Meaningless and Harmful. And here is Why.”. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/mbti-serious-test-why-robbrecht-van-amerongen

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 The Myers Briggs Foundation (2016) http://www.myersbriggs.org

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 Grant, Adam. (2013). “Say Goodbye to MBTI, the Fad That Won't Die”. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/20130917155206-69244073-say-goodbye-to-mbti-the-fad-that-won-t-die

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 “Myers-Briggs Type Indicator in Practice”. http://www.skillsyouneed.com/ips/mbti-in-practice.html

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 Pittenger, David J. (November 1993). “Measuring the MBTI... And Coming Up Short”. http://www.indiana.edu/~jobtalk/HRMWebsite/hrm/articles/develop/mbti.pdf

- ↑ Richards, Edythe. (2014)“Myers-Briggs® Myths and Misuse – MBTI® remains a useful tool”. http://atopcareer.com/myers-briggs-myths-and-misuse/

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Grant, Adam. (2013)“MBTI, If You Want Me Back, You Need to Change Too”. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/20130922141533-69244073-mbti-if-you-want-me-back-you-need-to-change-too?published=t