Case Study: Updating Airplane Tracking Systems in the Australian Defense Force

Developed by Rune Nedergaard

Contents |

About the Project

In 2012, the air-force division of Australian Defense Force (ADF) [1] launched a pioneering project, Updating Airplane Tracking Systems (UATS), with the objective to update the navigation systems of their aircraft, letting ground control track their positioning more accurately. This update of navigation system is caused by new international regulation, which states that all aircraft must update to an ADS-B positioning system, which will increase safety and efficiency of air travel. The project is divided in three stages:

- The Concept phase, in which the project group identified three aircraft types, from a potential set of five, that were suitable to upgrade.

- The Business Case Development phase, in which the project team worked on facilitating stakeholder agreements about the details of the upgrades, and prepared for the contractors to be able to work with these upgrades.

- The Execution phase, in which the project team works with ensuring the performance of the aircraft, and the security of the pilot.

The project is currently in stage three, with stage two completed in 2016, and stage three planned to be finished in 2018. The final business case in phase two was approved by the government, and is thus considered a success, while phase three and the overall project will be considered a success if the aircraft performs at the set expectations, while not compromising the safety of the pilot.

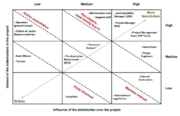

The project is led by project manager Rino Carrera. There have been several focus points throughout the course, for which Carrera has utilized different project management tools to secure project success. Some of these include identifying the purpose of the project, including for example scoping and goal setting, which Carrera used a Project Management Triangle for, identifying and satisfying the project stakeholders, which has been made clear with a Stakeholder Influence Matrix, identifying the scope and resourcing, and integrating this through time management utilizing a Critical Path Analysis, and risk management, through for example a Risk Cube.

Overall, the project has so far been a success thanks to Carrera’s usage of project management tools. This article will delve into some of the decisions Carrera has made while using these tools, and will have an especially in-depth look at the management of the stakeholders, in which Carrera used not only theory, but prior experience in order to set up proper communication, both internally in the team, and with external stakeholders, as well as the project’s risk management, in which Carrera may not have utilized the most optimal tools to fulfill the job.

Focus Areas

While project management leans heavily on specific tools and methods, several of these tools may fulfill similar, yet different purposes. When working with project management, it is of the utmost importance to identify for which purpose a method is used, and recognize whether or not said method is optimally used in the situation. While methods and tools aren’t static, and can often be bent to suit the needs of the user, the user may still get more mileage out of another, better suited method.

Similarly, sometimes simply using a project management tool isn’t enough to fully get an overview of a focus area. Sometimes critical thinking from the project manager’s side is all that is required for a project to flow much more smoothly. Incidentally, both of these theorems are somewhat applicable in Carrera’s project.

Stakeholder Management

Projects are done by people, for the benefit of (other) people. One of the most important jobs of a project manager is to identify for which people the project is relevant, and manage them accordingly. As UATS is a governmental project, it involves a lot of high-level stakeholders. Some of the most important key stakeholders, as identified by Carrera, are the end users, referred to as warfighters, or call pilots, as well as the design engineers who design the tracking systems.

External Stakeholder Management

Carrera let the pilots choose a spokesperson between them, referred to as the Lead Capability Manager (LCM). In addition to these two key stakeholders are a lot of other stakeholders, who does not have as great of an influence on the project, including committees, maintenance staff, support staff, external contractors, etc.

Carrera describes, that the two key stakeholders have wildly different personalities, with the LCM being very aggressive, and the design engineers and maintenance crew having a more relaxed attitude. Carrera practices constructive communication, which he has utilized to convince the LCM to accept a proposal, through employing active listening and focusing on the problem over the person. This has allowed Carrera to avoid any major conflicts in the project.

Internal Stakeholder Management

While managing external stakeholders is important, managing internal stakeholders, working directly on the project may be of even higher importance, as a project without a functioning team likely won’t be able to get work done to a satisfying degree. UATS, being a project with several factors, and directly influencing the ADF, is a rather large project, and thus also requires a relatively large project management team. Case in point, UATS had a management team of 24 individuals.

Carrera chose to split the management team up, not just in terms of groups but also in terms of location; the project management team was split into four groups, and spread across Australia. This decision was based on experience, as Carrera had in previous projects of similar size worked with a single, central team. This served a few purposes; in prior projects, external stakeholders felt isolated, while internal stakeholders became disconnected within the project, both of which led to an overall lower product quality. Reflectively, Carrera found that the internal stakeholders felt much happier due to a closer connection to the project management team, while the internal stakeholders didn’t feel as overwhelmed by the amount of people they had to work with. Carrera recognized that having a split team made communication much more of an issue comparatively, but this was a sacrifice, Carrera was willing to make, in order to increase stakeholder satisfaction.

In the case of UATS, splitting the project management team isn’t a decision Carrera took based on project management tools, but rather on experience. This does not mean that a project manager should always split up a larger team, as the decision can differ based on both the circumstances of the project, as well as the internal and external stakeholders. However, it does show, that some critical decisions can’t be deducted, simply by the usage of project management tools. A project manager may be required to decide on radical changes during the project, in a way that only good wit and experience will help.

Opportunity and Risk Management

There’s a certain degree of uncertainty involved when doing projects. A good project manager will do their best to mitigate risks, as well as seize opportunities when they appear. Whether a project manager successfully identifies and deals with these uncertainties or not may be the difference between a successful and a failed project.

During projects, it’s possible to split opportunity and risk management into proactive management and reactive management. Proactive management being predicting possible risks and opportunities, and planning mitigation or seizing-strategies ahead of time, and reactive management being reacting to previously unknown factors, as efficiently as possible, as to not compromise other elements of the project.

Risk Cube

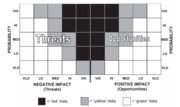

There are a few different tools that a project manager can use for opportunity and risk management. During proactive management, Carrera made use of a risk cube. By identifying as many of the various risks that may occur throughout the project, the risk cube makes it possible to quantify the overall level of the risks through their probability and severity [2]. Utilizing the risk cube gave Carrera an overview of the possible risks, and gave him insight in where to focus the project’s proactive risk management. This meant that Carrera got to focus most of the given resources on the most severe and probable risk; committee or government approval delay, while still spending some resources on proactively preventing some severe but improbable risks, and bypassing spending resources on rare risks with low impact.

Limits

While utilizing a risk cube gives the project manager an opportune way to manage possible upcoming risks, it doesn’t help identify possible opportunities that will occur throughout the project. While risk management is more important, due the possibility of the entire project crumbling due to unmitigated risks, grasping opportunities as efficiently as possible should be worth spending some time preparing. If unforeseen circumstances suddenly makes the project end up with additional budget or time, being prepared and thus able to use those resources as efficiently as possible can be key in progressing the project even more smoothly than initially anticipated.

Prospects of Improvement

One thing Carrera could have done is to use a double probability impact matrix instead, or in addition to the risk cube. The double probability impact matrix is very similar to the risk cube, in that it identifies and classifies risks based on probability and severity, but in addition it also lets the user assess opportunities.

While Carrera could have utilized the double probability impact matrix to assess both risks and opportunities, it may still not have been the correct decision to do so. The project team may have been limited on time, or they may have decided that they were unable to identify enough possible upcoming opportunities to be worth using the matrix. A project manager should be able to identify both risks and opportunities, but also be able to identify all possible useable tools, and decide which one is most suited for a given situation, if any.

Conclusion

Although there are some cases where Carrera strayed from common project management practice, in almost all cases, he did use project management tools to manage the project. However, a proper project manager must be able to not only follow theory and make use of project management tools, but also be able to deviate from the straight path if it suits the needs of the project. A project manager must be able to assess which tool at their disposal is best suited for the situation, or whether to use a tool in another way than originally intended. Additionally, it is critically important to be reflective and learn from past projects in order to avoid making the same mistakes.

Annotated bibliography

Source Material

Most of the information about the project was derived from several interviews with project manager Rino Carrera, done in the context of a prior paper on project management techniques and tools. Audio links can be found in the following files:

Notes from the interviews can be found in the following files:

- Interview 1: [3]

- Interview 2 - About complexity: [4]

- Interview 2 - About uncertainty: [5]

- Interview 2 - Extra questions: [6]

List of Risks

This is a list of the risks identified by the project team. These are also the risks that can be viewed in the risk cube. The risks are described and assigned a level equivalent to their overall probability and severity, along with a mitigation strategy, and a risk level after mitigation. [7]

AIR90 Overview

This is an overview of the project’s schedule. It includes some business rules, a proposed acquisition concept, an organisatorial resource strategy, a schedule for the activities throughout the project, resource charts for both money and personnel, and the risk cube. [8]

Contracting

This document involves some information about the accountability in the design of the tracking system, and how the project and system gets approved and reviewed. Part of these pages are missing due to confidential information. [9]

Capability and Engineering

This document includes information about the ADF’s Defense Materiel Organisation’s purpose, goals, mission, capability, capability-development lifecycle, key stakeholders as identified by the project manager, life cycle cost and function and performance specifications. Part of these pages are missing due to confidential information. [10]

Gantt Chart - Critical Path

This is a gantt chart describing the critical path of the project, eg. the fastest possible completion of the project through the processes that require each other to be completed beforehand. [11]

References

[1] Royal Australian Air Force Home (visited 21-09-2017) [12]

[2] gpm first Managing Risks in Practice (2017) visited 21-09-2017 [13]

[3] Bright Hub Project Management A Critical Tool for Assessing Project Risk (2015) visited 22-09-2017 [14]