Critical Chain Project Management to cope with uncertainty

Critical Chain Project Management(CCPM) is an approach for managing project, initially developed by M. Goldratt and based on the Theory of Constraints(TOC) applied to project management. It has adquired increased importance since it has been proved to be an effective method to ensure project completed on time, reduction of project completition time, and increased resource productivity. The basics principle are: avoiding multi-tasking, focus on the critical chain tasks, aggregate all safety time to handle uncertainty

This article illustrates the theory behind the method, its application, [a comparison with the critical path method], and its limitation.

Critical Chain Project Management(CCPM) is a method to plan, execute, manage, and control both single and multi projects, which emphasizes the effects of resource allocation and activity duration uncertainty. CCPM is an outgrowth of the Theory of Constraints(TOC) and was introduced in 1997 in Eliyahu M. Goldratt’s book, “Critical Chain”[1] in response to many projects resulted in larger duration, increased cost, and less derivable than expected.

The Critical Chain method mainly differs from the traditional methodology, deriving from Critical Path, in how uncertainty is handled.

Contents |

Theory of Constraints

Since CCPM applies TOC’s concepts to project management, it is useful to understand the reasoning behind the theory.

TOC is a systems-management philosophy, originally applied to production system, based on the principle that any system must have a constraint that limits its output. If there were no constraints, system output would either rise indefinitely or would fall to zero.

Therefore, a constraint( or bottleneck) limits any system with a nonzero output[2].

A system’s constraint may be physical (e.g. materials, machines, people, demand level) or managerial[3] which hinders the system to achieve better performance.

At first, “before we can deal with the improvement of any section of a system, we must first define the system’s global goal; and the measurements that will enable us to judge the impact of any subsystem and any local decision, on this global goal.”[4]. Then in order to improve the system’s performance, the limiting constraint must be found and improvement efforts should be placed on elevating the capacity of that constraint.

Goldratt defined the “five focusing steps” as an continuous improvement process[5]:

1. Identify the system's constraint(s)

2. Decide how to exploit the system's constraint(s)

3. Subordinate everything else to the above decision

4. Elevate the system's constraint(s)

5. If, in the previous steps, the constraint has been broken, go back to step 1, and do not allow inertia to cause a system's constraint

The five steps process permits to identify the most detrimental constraint. When the latter is solved, the next constraint needs to be identified and addressed. Therefore, it is a continuous improvement process.

TOC applied to Project Management

Concepts and principles of CCPM are obtained by applying the TOC improvement process to Project Management.

In order to apply the five steps, it is necessary at first to define the goal of a project. The primary goal of a project is considered to be the promised project due date.

1. Identify project’s constraint

According to the TOC, the part of the system that constrains the objective is the Critical Chain, which is defined as “the longest chain of

precedence and resource dependent tasks that determines the overall duration of a project”. Defining the constraint of a project in

terms of the schedule derives from the impact that schedule has on project cost and project scope. The three conditions are dependent[6].

Since the Critical Path does not account resource allocation while determining a schedule, if resources would be infinite then Critical Path and Critical Chain would be identical.

2. Decide how to exploit the project’s constraints This step can be translated in focusing on the activities of the Critical Chain to ensure efficient performance and no delays. In order to achieve this, the critical factors leading to delays should be identified.

3. Subordinate everything else to the above decision Applied to project, it means that all the non-critical activities must not affect or delay any activity on the critical tasks.

4. Elevate the project’s constraints When no more improvement can be obtained, this step suggests to invest in additional resources, or increase the capacity of resources that can benefit most the critical chain performance.

5. If, as a result of the previous steps, the constraint has alleviated, return to Step 1

Undesired effects of traditional approaches

1. Excessive Activity Duration Estimates

People, when are requested to estimate an activity duration, attempt to make commitments that they could meet with a high level of certainty (An investigation into the fundamentals of critical chain project scheduling, Herman Steyn). In addition, managers selectively remember the

instances where activity duration estimates were exceeded, and therefore wants to add contingency of his own.The combination of both actions lead to a final duration estimation with a probability of completion of 80% to 95% on or less than the activity duration estimate.(PAG 19)

2. Performance overrun estimates

Even tough, as previously stated, the estimates are quite padded, performance exceeds estimates.

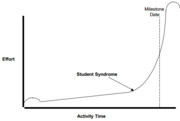

Many people have a tendency to wait until activities get really urgent before they work on them.(CCPM Improves Project Performance, Leach1999) This tendency is better known as Student Syndrome: a person will only start to apply themselves to an assignment at the last possible moment before its deadline(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Student_syndrome)

By acting in this way, people tend to waste their contingency before they start the activity, forcing them to perform most of the work in the later portion of the scheduled activity time. Then, in problems occur, there is no time to recover. (CCPM Improves Project Performance, Leach1999) PICTURE

Critical Chain Method

Applications

Procedure

Limitation

References

- ↑ http://www.goldratt.co.uk/resources/critical_chain

- ↑ Lawrence P. Leach, 2005, Critical chain Project Management, 2ed, Artech House, ISBN 1-58053-903-3

- ↑ Rahman S., (1998), Theory of Constraints: A review of the philosophy and its applications, International Journal of Operations and Production Management. 18(4), pp. 336-355

- ↑ Goldratt, Eliyahu M., (1990), Theory of Constraints, Croton-on-Hudson, NY: North River Press

- ↑ Graham K. Rand, (2000), Critical chain: the theory of constraints applied to project management, International Journal of Project Management 18, pp. 173±177

- ↑ Larry P. Leach, (1997), Critical Chain Project Management Improves Project Performance, Advanced Projects Institute