Critical Chain Project Management to cope with uncertainty

This article illustrates the theory behind the method, its application, [a comparison with the critical path method], and its limitation.

Critical Chain Project Management(CCPM) is a method to plan, execute, manage, and control both single and multi projects, which emphasizes the effects of resource allocation and activity duration uncertainty. It has demonstrated over the past 10 years its ability to significantly reduce the duration of projects, to ensure that projects are completed on time, and to increase resource productivity.[1]. CCPM is an outgrowth of the Theory of Constraints(TOC) and was introduced in 1997 in Eliyahu M. Goldratt’s book, “Critical Chain”[2] in response to many projects resulted in larger duration, increased cost, and less derivable than expected.

The Critical Chain method mainly differs from the traditional methodology, deriving from Critical Path, in how uncertainty is handled.

Contents |

Theory of Constraints

Since CCPM applies TOC’s concepts to project management, it is useful to understand the reasoning behind the theory.

TOC is a systems-management philosophy, originally applied to production system, based on the principle that any system must have a constraint that limits its output. If there were no constraints, system output would either rise indefinitely or would fall to zero.

Therefore, a constraint( or bottleneck) limits any system with a nonzero output[3].

A system’s constraint may be physical (e.g. materials, machines, people, demand level) or managerial[4] which hinders the system to achieve better performance.

At first, “before we can deal with the improvement of any section of a system, we must first define the system’s global goal; and the measurements that will enable us to judge the impact of any subsystem and any local decision, on this global goal”[5]. Then in order to improve the system’s performance, the limiting constraint must be found and improvement efforts should be placed on elevating the capacity of that constraint.

Goldratt defined the “five focusing steps” as an continuous improvement process[6][5]:

1. Identify the system's constraint(s)

2. Decide how to exploit the system's constraint(s)

3. Subordinate everything else to the above decision

4. Elevate the system's constraint(s)

5. If, in the previous steps, the constraint has been broken, go back to step 1, and do not allow inertia to cause a system's constraint

The five steps process permits to identify the most detrimental constraint. When the latter is solved, the next constraint needs to be identified and addressed. Therefore, it is a continuous improvement process.

TOC applied to Project Management

Concepts and principles of CCPM are obtained by applying the TOC improvement process to Project Management.

In order to apply the five steps, it is necessary at first to define the goal of a project. The primary goal of a project is considered to be the promised project due date.

1. Identify project’s constraint

According to the TOC, the part of the system that constrains the objective is the Critical Chain, which is defined as “the longest chain of

precedence and resource dependent tasks that determines the overall duration of a project”. Defining the constraint of a project in

terms of the schedule derives from the impact that schedule has on project cost and project scope. The three conditions are dependent[7].

Since the Critical Path does not account resource allocation while determining a schedule, if resources would be infinite then Critical Path and Critical Chain would be identical.

2. Decide how to exploit the project’s constraints This step can be translated in focusing on the activities of the Critical Chain to ensure efficient performance and no delays. In order to achieve this, the critical factors leading to delays should be identified.

3. Subordinate everything else to the above decision Applied to project, it means that all the non-critical activities must not affect or delay any activity on the critical tasks.

4. Elevate the project’s constraints When no more improvement can be obtained, this step suggests to invest in additional resources, or increase the capacity of resources that can benefit most the critical chain performance.

5. If, as a result of the previous steps, the constraint has alleviated, return to Step 1

Undesired effects of traditional approaches

1. Excessive Activity Duration Estimates

People, when are requested to estimate an activity duration, attempt to make commitments that they could meet with a high level of certainty[8]. In addition, managers selectively remember the

instances where activity duration estimates were exceeded, and therefore wants to add contingency of his own. The combination of both actions lead to a final duration estimation with a probability of completion of 80% to 95% on or less than the activity duration estimate[7].

2. Performance overrun estimates

Even tough, as previously stated, the estimates are quite padded, performance exceeds estimates.

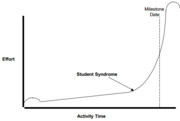

Many people have a tendency to wait until activities get really urgent before they work on them[7]. This tendency is better known as Student Syndrome: a person will only start to apply themselves to an assignment at the last possible moment before its deadline[9]. By acting in this way, people tend to waste their contingency before they start the activity, forcing them to perform most of the work in the later portion of the scheduled activity time. Then, if problems occur, there is no time to recover[7].

3. Failure to pass on early completion

Analysis of almost any project’s results reveals that people report very few activity as completed early[7]. Since the estimates are usually around 80-90% of probability of completion, the results should shown an higher number of activities completed early. On the one hand, the reason behind those result is the relationship between the level of performance and the established goal. If applied to Project Management environment, it leads to the Parkinson’s Law. The latter described by Parkinson(1957) as “work expands so as to fill the time available for its completion”. A loose deadline(i.e. lowering the goal), leads, thus, to a decline of the worker’s performance and to a delay of the activity[10].

On the other hand, even if activities completed early, people fail to report. People have little or no reward on early completion. In addition, if the activity is completed early, the worker gets more to do, and the next time he will have to replicate the same performance. In other words, reducing future estimates for the same task.

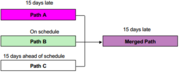

4. Activity path merging creates delay

Usually projects have multiple activity paths which must merge into the critical path before the completion of the project. Merging activity paths means that all of the feeding paths(activity path that merges or feeds the critical one) are required to start the successor activity.

Therefore, the successor activity can not start until the latest of the merging activities completes[7]. In a scenario as the one represented by figure 4, even if a feeding path is completed in advance, the positive variation is wasted.

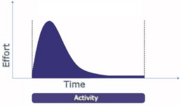

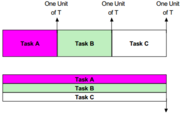

5. Multitasking: increase the completion time

An additional reason which contributes to make tasks longer is multitasking. When an individual is working on more than one activity/project simultaneously, for instance three, each task completion time would result in a three time longer duration. This occurs since the individual spends one third of its time in each activity, causing an extension in the project duration as the successor activity has now to wait three times the original duration of the single task . Figure 5 helps to better understand

Critical Chain Method

Applications

Planning

The first step in order to apply CCPM consist of defining an initial schedule taking in consideration task duration estimates and dependencies. In other words, the initial schedule could be also defined as the “infinite capacity schedule” since the resource availability is not considered yet. This initial step has to be PERT?? Backward process project due date.XXXXXXX Thereafter, the schedule must be adjusted by positioning the tasks according to the capacity and availability of the resources. Because at least some of the resources have limited availability, the resulting schedule is likely to be longer than the schedule obtained with the basic Critical Path Method, as critical activities are delayed while waiting for the resources they require[11]. Then, the longest sequence of activities needed to complete the project taking into account both the interdependencies and resource capacity is defined as the Critical Chain. Next step involves shortening duration estimates, removing the safety margin from each critical task and pooling them together at the project buffer. The latter is place at the end of the project, and represented as a task.

'''*can be less than the sum of safety margins remove at task level.'''XXXXX

Then, the same process of grouping safety margins is applied to the non-critical paths. The safety margins of each non-critical path are grouped into a feeding buffer placed where the path merges into the critical chain path.

Execution

Once the new project schedule is created, consisting of tasks with reduced durations and different types of buffer, the project manager needs to execute the project plan. During this phase, the resource working on the critical chain activities must work continuously on a single activity at time. They are not allowed to work on tasks in parallel in order to avoid multitasking, for the reason explained above. To further enforce the resource behaviors a “Relay Runner” mentality is included in which resources begin work as soon as assigned, work without interruption until done, and announce when they finish immediately when task criteria is fully met[12]. In case of early completion of a task, work on the successor activity must begin rapidly. In the opposite scenario, there is no reason for immediate concern, as the buffer will absorb the delay [11].

Control

In CCPM, managing and tracking of project performance is based on buffer consumption: as the project progresses, the manager constantly check how much of the buffer is consumed to protect both the critical chain(Feeding Buffer) and the project due date(Project Buffer) from disruption. Buffers are supposed to act as transducers that provide vital operational measurement and a proactive warning mechanism. If activity variation consumes a buffer by a certain amount, a warning is raised[13]. Then, if the consumption rate is quite high so that the whole buffer could be consumed before the end of the project, corrective actions must be taken.

In order to have facilitate the monitoring and evaluation of the buffer consumption, buffers are usually divided in three third, respectively represented as Green zone, Yellow zone, Red zone. The level of buffer consumption gives management visible signals:

- Green zone: no action

- Yellow zone: assess the problem and prepare for action

- Red zone: corrective action must be implemented

Through this mechanism, buffer management provides a unique anticipatory project-management tool with clear decision criteria[3].

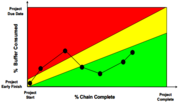

However, the buffer consumption has to be combined with the project completion to reflect a clear and accurate project status. The tricolored chart used to visualize the project status, where the buffer consumption is plotted against the project completion(both expressed as a percentage), is called Fever Chart.

Procedure

Limitation

References

- ↑ Marris P., (2011), La chaîne critique pour réduire le time to market et accroître la productivité, STP PHARMA PRATIQUES vol.21 N°5

- ↑ http://www.goldratt.co.uk/resources/critical_chain

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Lawrence P. Leach, 2005, Critical chain Project Management, 2ed, Artech House, ISBN 1-58053-903-3

- ↑ Rahman S., (1998), Theory of Constraints: A review of the philosophy and its applications, International Journal of Operations and Production Management. 18(4), pp. 336-355

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Goldratt, Eliyahu M., (1990), Theory of Constraints, Croton-on-Hudson, NY: North River Press

- ↑ Graham K. Rand, (2000), Critical chain: the theory of constraints applied to project management, International Journal of Project Management 18, pp. 173±177

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 Larry P. Leach, (1997), Critical Chain Project Management Improves Project Performance, Advanced Projects Institute

- ↑ Steyn H., (2000), "An investigation into the fundamentals of critical chain project scheduling", International Journal of Project Management 19, pp. 363-369

- ↑ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Student_syndrome

- ↑ Gutierrez G. J., Kouvelis P.,(1991), “Parkinson’s law and its implication for Project Management”, Management Science Vol. 37, No. 8

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Raz T., Barnes R., Dvir D., (2003), A critical look at critical chain project management, Project Management Journal, vol. 34

- ↑ Kirpes C., (.2014), ‘’Evaluating the Use of Scheduling Techniques: Critical Chain Project Management’’, Proceedings of the 2014 Industrial and Systems Engineering Research Conference Y. Guan and H. Liao, eds.

- ↑ Herroelen W., Leus R., (2001), ‘’On the mertis and pitfalls of critical chain scheduling’’, Journal of Operations Management, vol. 19, pp. 559-577