Daniel Kahneman's two systems of thinking

Written by Johan Holger Rasmussen

“Questioning what we believe and want is difficult at the best of times, and especially difficult when we most need to do it” (Kahneman, 2012, page 3) [1]. In many ways, this claim describes Kahneman’s over all mission with his bestselling book, “Thinking fast and slow”, in which he seeks to show the reader, how our everyday decision making is filled with biases.

During the book, psychology professor and economic Nobel prize winner, Daniel Kahneman, takes us through the pitfalls, into which all of us tend to fall, without even knowing it. His argument is based on the claim, that every single decision, we as humans make, is based in the so-called system 1 and system 2.

According to Kahneman, system 1 rely on knowledge and routine and is engaged when a subject is dealing with a task that requires little to no effort, e.g. simple mathematical calculations, or routine work [1]. On the other hand we have system 2, which is engaged when the subject is dealing with tasks in which attention is required and necessary for completing the task, e.g. searching for a specific person in a crowd or parallel parking a car [1]. Both systems run simultaneously whenever we are awake, normally system 2 is in a low effort mode, where system 1 "continuously generates [...] impressions, intuitions, intensions and feelings" (Kahneman, 2012, page 24) [1]. These impressions and intuitions can be turned into beliefs and voluntary actions by system 2. In decision making under uncertainty, a cognitive bias can thus interfere with the decision-making process and have an impact on the thinking of system 2. It is therefore a general misunderstanding that humans think logically, which is why the two systems are relevant in project management. When managing a project, it is crucial that we are aware of potential biases, within our own and colleague’s decision making. This is crucial because of, when being aware of the biases, it is possible to prohibit them, with an array of different project management tools.

This article will focus on the correlation between the two systems of thinking and products of biases in project management. More precisely the article will investigate the two systems internal interaction, as well as 4 different products of biases which are the anchoring effect, the planning fallacy, the control illusion and the denominator neglect.

Contents |

Introduction to the two systems

It has been known for several decades that’s humans have two different modes of thinking, even though this theory has been given a variety of titles. Kahneman adopts the terms system 1 and 2 with the following definition:

System 1 is fast and automatic and works with little or no effort, and include innate skills, as recognizing objects, persons, and places as well as orienting attention to important events around us. System 1 include driving a car on an empty road or orienting yourself towards a loud noise. When asked the question 2+2=, people will, if having a basic understanding for mathematics, unavoidably think of number 4. This is because the mind has learned to link the two assertions together [1]

System 2 allocates attention to mental activities that requires it, which means that it would not be possible to for system 2 to focus on several attention requiring activities at once, like calculating larger multiplications while focusing on when a traffic light turns green [1].

Most of the time, system 1 runs in an automatic state that continuously generates suggestions, intuitions, etc. for system 2, which if approved, can be turned into actions, without much effort from system 2. In a situation where system 1 can’t handle a problem or a task by itself, it will call for system 2, like when asked to calculate a larger mathematical multiplication [1]. The biggest hurdle in the way that the two systems work, is that system 1 can create biased suggestions and intuitions for system 2 and that system 1 can’t be turned off, and therefore it will always report to system 2, even though system 2 disapproves the suggestion. On the other hand, it would not be possible only to rely on system 2, both because of the speed of which it operates in, but also because of the limited span of attention it can give .

It has been showed that people how are engaged in task that requires attention for a longer period, generally perform worse in a second task afterwards. This concept is known as ego depletion and occurs because of the small timespan that system 2 can be engaged. If a subject is engaged emotionally in a task for a period, the subject is faster to quit the next task. It is though possible to engage system 2 in several task after each other, there just need to be a strong incentive behind it for the person [1] .

As mentioned earlier, system 2 continuously gets information, suggestions, and intuitions from system 1, and have to process and control it. One weakness about this, is what Kahneman describes as the lazy system 2. In a situation where information from system 1, seems like routine work, system 2 will in some situations approve it, which in some situations leads to mistakes. Under the circumstance where this happens it is most likely because of lack of motivation. Everyone has the option to slow down and think about the problem, but most people let their system 2 endorse the thinking of system 1, and thereby lack critical thinking.

The two systems importance in project management

A project is undertaken to create a “unique product, service or result" (PMI, 2017, page 4) [2] and therefore it a task that differs from routine work. There are continuously decisions to be made, all of which have an impact on the final product, system, or result, and therefore system 2 is engaged many times throughout any given project. That is why it is important for project managers and generally stakeholders in projects to be aware of the two systems, how they interact with each other, and to know how to prohibit or enhance the effects of the two systems.

The interaction of the two systems, will create biases, that can affect the ways we approach projects, programs and portfolios. In the book Kahneman describes several “products” of different biases, that he names effects, fallacies, illusions, and neglects. In the following four different products of decision biases will be presented: (1) the anchoring effect, (2) planning fallacy, (3) the control solution, (4) denominator neglect. In the following it will be discussed how and why these bias' products are important to project management, and elaborated on the solutions at hand, which given project management tools enable.

Bias and the two systems in project management

The anchoring effect

Earlier research done by Kahneman together with Amos Tversky showed, that when people were presented with a number about a subject before asked to take a stand on the same subject, the number presented would have great impact on the final decision [1]. Kahneman exemplifies this by asking if Gandhi was younger or older than 144 years, when he died. This question has the reader anchoring at 144, and even though we know that Gandhi of cause did not reach the astonishing 144 years, we now believe him to have died at a very high age. This is what is called the anchoring effect. Even in situations, where there is no logical correlation between the anchor presented to people and their answer about a different subject, the anchor would still have an impact on the answer. This is one of the things that makes system 2 susceptible to biasing influences, and therefore a vital weakness in projects and decision making in general. As cited earlier, system 2 is continuously influenced with impressions, intuitions etc. from system 1 which means that people, reluctantly, make decisions without having a logic argumentation.

There are several parts of projects where the anchoring effect is important to consider, e.g: project cost management (PMI, 2017, chapter 7) [2]. Consider the following situation, a project manager is continuously working on two projects which is far from each other in cost. When shifting between the two projects, the former project is going to make an anchor in the projects manager’s mind. E.g., in the larger project the project manager has to order 1000 windows for a construction project, and because of the large quantity, the project manager can get a considerable discount, but would still have to accept a high total price. When the project manager then soon after starts working on the other smaller project, this price would have left an anchor. Which means that the project manager, both would make higher estimates of total cost, but also lower estimation cost per window/unit because lack of quantity discount.

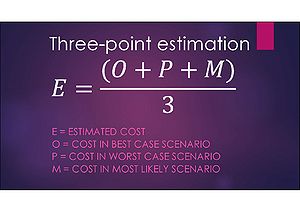

But there are ways to overcome this, one of these is the three-point estimation [2], shown at the figure to the right. The tool’s purpose is to take the worst- and best-case scenario into consideration, when estimating a cost.

This tool, to be fair, does not completely eliminate the anchoring effect. This is because the most likely scenario, which the project manager uses in the formula, will properly be affected by his or her anchor. But the tool minimizes the effect of it when taking the average of the three scenarios and together with awareness of anchoring, the project manager will most likely do a better job at cost management.

The planning fallacy

Another problem, which Kahneman introduces is the planning fallacy. According to Kahneman, people involved in projects generally underestimate the time and resources needed for finishing the project or a task within the project, as well as overestimating the final impact of the project. Kahneman and Tversky uses the term planning fallacy to describe this bias, with the definition that the people involved in a project will predict an unrealistic and close to best-case scenario, and thereby overestimating their own abilities and the projects outcome. The main reason for planning fallacy is the optimistic bias, which is a bias that makes people think that they are less likely be victims to negative events. Another reason is the participants’ lack of knowledge or allowance to what is called the unknown unknowns, which in project management, can be future events or hurdles that the participants of a project are unaware or cannot understand. This bias can be improved by comparing the project to statistics of similar projects [3]. When people involved in a given project becomes aware of the outcome attained by similar work, overly optimistic forecasts might be adjusted down, making them more realistic.

Another thing discovered by Kahneman is the tendency to ignore anchors, when operating under the planning fallacy. E.g., the same project manager as before, with an anchor which says that windows always end up being more expensive than first assumed, may end up ignoring this anchor, because of his or hers overly optimistic bias. The project manager just might think “this time will definitely be different, because I have new knowledge”, and thereby ignoring external factors which impacts the costs of windows. Thereby the optimism bias overshines the anchoring effect.

One way to overcome this is to do an optimism bias adjustment, which is a technique developed by the British HMS treasury, where cost estimations are increased, depending on how unique the project is [4]. As an example, a one-of-a-kind prestige construction project will be imposed a greater increase in costs, than a standard social housing project would. This is because the latter requires a range of standard materials and methods and because the team is familiar to this type of project, whereas the prestige project might lead to several unknow obstacles.

The control illusion

Also known as the illusion of control, the control illusion is a state whereas individuals believe they have more control over a situation that they actually do. This makes people misjudge decisions, mainly because of their lack of knowledge of a situation, which can lead to underestimating of external influences. The illusion is partly influenced by the optimism bias, that makes people think that the future is bright, and therefore doesn’t take risk into consideration. System 1 is the prime influence in the illusion of control, because it is fast to come up with solutions to things, which sometimes people don’t have control over [1].

The control illusion is important to consider when working in project management, simply because of the fact, that the job consist of controlling projects, and therefore stakeholders can misinterpret that a project manager can control everything within their field.

When working within project integration management, and especially within process monitor and control project work (PMI, 2017, page 105) [2], it is useful to consider the control illusion. The work within monitoring and controlling projects, consist of tracking, reviewing, and reporting the progress of the project to compare it with the overall performance objectives. The input to a consists of, among others, project documents such as schedule forecast (PMI, 2017, figure 4.10) [2]

The schedule forecast uses the past performances in the project to determine the future, and if working on this without considering the control illusion, one can overestimate the team’s future performance against upcoming task.

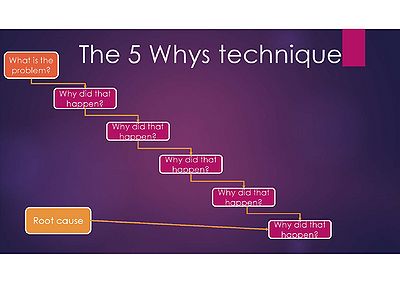

One solution to work against the control illusion is to use the 5 whys technique to find the root cause of a problem that has happened in the past. The main reason that the 5 whys technique work is that a problem which normally would get assessed by system 1, now must get answered by 5 questions in correlation, and therefore eliminates the fast thinking of system 1.

The denominator neglect

When presented chance of events happening, no matter if it is positive or negative for the project, the way the chance is presented have a large impact on how individuals process it. If presented with the chance as a fraction, people tend to focus a lot more on the numerator, than the numerator compared to the denominator. Kahneman presents the example that students are presented with two urns where the first contains 1 red marble out of 10, and the second contains 8 red marbles out of 100. They then afterwards must pick an urn to draw a marble from where they win a prize, if they draw a red marble [1].

Again, here system 1 is the prime influencer on this neglect, because 30-40% of the students picked the urn with 8 red marbles, which is also the urn with the least chance of winning a prize. This is because system 1 paints a picture of 8 red marbles laying in a pool of non-prize marbles, and the same goes for the first urn, where the only is one winning marble [1].

Even though the test subjects are university students, which assumable are good enough at fractions, that they can calculate the chance of drawing a winning marble, a large part of them answers before they initiate the system 2.

The denominator neglect is important to consider in project risk management among others, and especially when representing risk to other team members and stakeholders. When assessing risk management, it could be an idea to consider the reporting formats (PMI, 2017, page 408) [2]. This is important so that when presenting risk, the project manager does not favor any specific stakeholder, if presenting and reporting the risk consistently throughout the project.

Annotated bibliography

Kahneman, D. (2012) Thinking, fast and slow . London: Penguin. The book on which this article mainly is based upon. In this article, only a handful of the differents products of biases is presented as in the book, where they also are elaborated more, though not always relevant in project, program and portfolio management.

Project Management Institute, Inc.. (2017). Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide) (6th Edition) Is used in the article to angle the different theories from the book thinking, fast and slow into different project management phases. In some cases the PMI standard is also used as for tools to prohibit the different products of biases

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 Kahneman, D. (2012) Thinking, fast and slow . London: Penguin.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Project Management Institute, Inc.. (2017). Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide) (6th Edition)

- ↑ Flyvbjerg, B. (2006) ‘From Nobel Prize to Project Management: Getting Risks Right’, Project Management Journal, 37(3), pp. 5–15. doi:

- ↑ Supplementary Green Book Guidance: Optimism Bias (2003).