Integrated Project Delivery (IPD)

(→Multi-Party Agreements) |

(→Multi-Party Agreements) |

||

| Line 80: | Line 80: | ||

===Multi-Party Agreements === | ===Multi-Party Agreements === | ||

| − | [[File:Aspects_of_IPD_agreement.PNG|thumb|right|500px|Figure 2: Main Aspects of IPD Agreement <ref name=''AGREEMENT'' | + | [[File:Aspects_of_IPD_agreement.PNG|thumb|right|500px|Figure 2: Main Aspects of IPD Agreement <ref name=''AGREEMENT''/>]] |

<ref name= ''Ghassemi_IPD''> ''Ghassemi, R. & Beceric-Gerber, B., (2011). Transitioning to Integrated Project Delivery: Potential barriers and lessons learned '' </ref> | <ref name= ''Ghassemi_IPD''> ''Ghassemi, R. & Beceric-Gerber, B., (2011). Transitioning to Integrated Project Delivery: Potential barriers and lessons learned '' </ref> | ||

According to the AIA Californian Counsel (2007a, p. 32), “In a multi-party agreement (MPA), the primary project participants execute a single contract specifying their respective roles, rights, obligations, and liabilities”. Each party’s contributions and interests are known to everyone. Trust is required as compensations come from project success. Project success is dependent on the participants’ commitment to work together as a team. Integrated teams are creative and flexible, | According to the AIA Californian Counsel (2007a, p. 32), “In a multi-party agreement (MPA), the primary project participants execute a single contract specifying their respective roles, rights, obligations, and liabilities”. Each party’s contributions and interests are known to everyone. Trust is required as compensations come from project success. Project success is dependent on the participants’ commitment to work together as a team. Integrated teams are creative and flexible, | ||

Revision as of 20:02, 28 February 2019

Contents |

Abstract

Integrated project delivery (IPD) is an emerging construction project delivery system that aligns different stakeholders’ interests and objectives, while collaboratively involving key participants very early in the project timeline. It is distinguished by a multiparty contractual agreement that incentivizes collaboration and allows risks and rewards to be shared among the parties of the contract. IPD is becoming increasingly popular with various organizations expressing interest in its benefits to the construction industry. The objective of the article is to provide a description of the IPD method and a short discussion on how it has been rising as a promising method to avoid some of the inefficiencies of traditional contracting systems, as a way to reduce the conflictual relationships between the parties involved in construction projects and maximize construction project success. Furthermore, This article seeks to illustrate what are the main benefits of IPD and address the main obstacles that refrain from unlocking the value of IPD as a precursor of a larger adoption in the industry. IPD has emerged as a solution for lack of schedule and budget compliance and wasted resources, though its implementation is not without challenges and limitations.

Definition of IPD

There is no single definition for IPD. In fact, numerous definitions can be found throughout published studies and reports, some of the definitions continue to evolve. Mathews and Howell (2005) define IPD as “a relational contracting approach that aligns project objectives with the interests of key participants.” Formally, Integrated project delivery (IPD) is defined as a project delivery approach that integrates people, systems, business structures and practices into a process that collaboratively harnesses the talents and insights of all participants to optimize project results, increase value to the owner, reduce waste and maximize efficiency through all phases of design, fabrication, and construction. [1] . (American Institute of Architects)

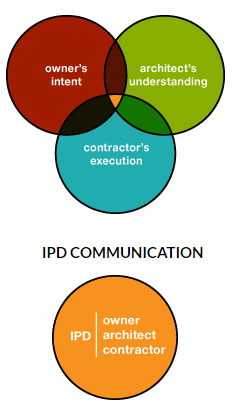

IPD principles can be applied to a variety of contractual arrangements and IPD teams can include members well beyond the basic triad of owner, architect, and contractor. In all cases, integrated projects are uniquely distinguished by highly effective collaboration among the owner, the prime designer, and the prime constructor, commencing at early design and continuing through to project handover.

The current form of IPD was born out of the general belief that traditional contracting approaches create barriers to collaboration, transparency and the trust needed to truly collaborate; hence the rise of the multi-party agreement. The intent of the multi-party agreement is to create a contractual vehicle that removes barriers to collaboration (i.e., protecting profit, blaming others, hiding contingency and the mentality of every company for itself). There are many IPD proponent in the industry who believe this environment can only be created through the use of a multi-party agreement in which there are a shared risk/reward pool and no traditional financial cost guarantees.

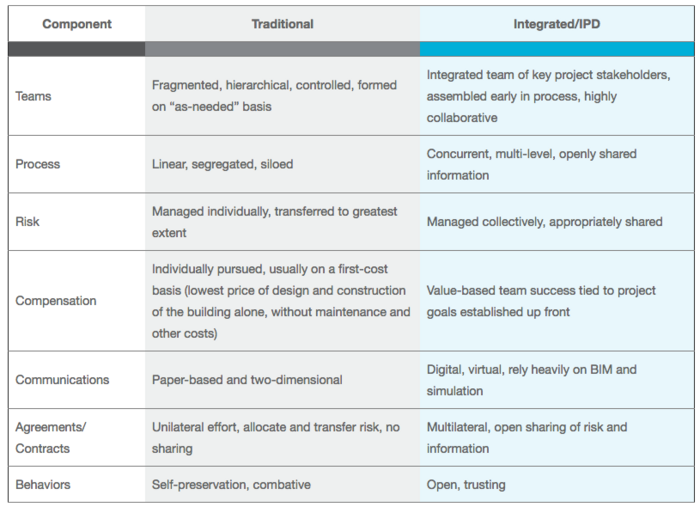

Differences between IPD and traditional delivery methods

A summary of the major differences between traditional project delivery and integrated delivery is shown in Table 1.

And in practice, there can be more differences between IPD and design-build [2] :

- Procurement method: Best practices in design-build may use either qualification based selection or the best value model, where price as well as non-price, qualitative factors are taken into account. In the multi-party IPD model, only qualifications-based selection may be used.

- A degree of owner involvement: In the design-build model, the owner defines the performance expectations for the project (often with the design-builder’s input), while the design-builder is responsible for managing the details of design and construction. The owner can select its level of participation along with a broad spectrum: from fully participatory to a more delegatory approach. In the IPD model, the contracting parties form a team which assumes joint responsibility for both the definition of the project and the management of the process.

- Price and schedule commitments: In design-build, the owner typically receives commitments for price and completion date early in the process. In the multi-party IPD model, the owner does not receive price or schedule guarantees from the other parties. The owner pays for the cost of the work, even if it exceeds the budgetary goal and even if the project is delivered late.

- Accountability and risk: The design-builder accepts risk for designing and constructing the project in accordance with the project criteria and the owner can look to the design-builder as a single point of accountability. In the multi-party model, by contrast, the owner contracts with at least two other parties and yet retains ultimate accountability and risk for decision-making and the project outcome.

In a 2005 paper, Owen Matthews and Greg Howell (REF), a Florida based constructor, listed four problems with the ‘traditional’ contractual approach:

1.Good ideas are held back – late involvement of specialist constructors deprives the design team of the opportunity to develop innovations with those who will deliver the project.

2.Contracting limits cooperation and innovation - … the system of subcontracts that link the trades and form the framework for the relationships on the project … detail exactly what each subcontractor [is] to provide…, rules for compensation, and sometimes useful, if unrealistic, information about when work [is] to be performed. The 20 to 30-page subcontracts mostly [deal] with remedies and penalties for noncompliance. These contracts [make] it difficult to innovate across trade boundaries even though the work itself [is] frequently inter-dependent. (It is hard to have a wholesome relationship … when you have a charge of dynamite around your neck and the other holds the detonator.) Of course, horse- trading always takes place…, but for “equal” horses. Trading a small increase in effort by one contractor for a big reduction for another, a horse for a pony, [is] almost impossible.

3.Inability to coordinate - …… no formal effort to link the planning systems of the various subcontractors, or to form any mutual commitments or expectations amongst them. Project organizations looked like 20 or more rubber balls, representing subcontractors, all tethered to a single point by long elastic bands. When the connection point [is] jiggled, the balls jiggled in all random directions colliding with each other in unusual and unexpected ways.

4.The pressure for local optimization - each subcontractor fights to optimize their performance because no one else will take care of him. The subcontract … and the inability to coordinate drives us to defend our turf at the expense of both the client and other subcontractors. Remember that everyone on the project other than the prime contractor is a subcontractor. These subcontractors frequently, in their life outside of the subcontract, may be generous, caring and professional. However, since right or wrong is defined by the subcontract, more often than not, they take on a very legalistic and litigious stance becoming an army where the rules of engagement are “Every man for himself.”

Traditional methods can be a catalyst for an anti-collaborative, “every man for himself” mindset — this is unfortunate because the owner may never realize the strength of fully integrated teams. Architects and engineers don’t fully engage with contractors under the traditional DB process. Also, subcontractors often follow engineering assumptions without being coordinated or validated by design professionals. Once value engineering or another scope/price reductions occur, the designer often asks for additional fees to rework drawings to reflect the contractor’s input. These time and cost overruns lead to potentially more adversarial roles between designers and contractors. In contrast, IPD is all about highly collaborative interactions, shared risk, and team building, where the key participants are involved as early as practicable [3].

Traditional project delivery incentivizes uncoordinated behaviour by tying firm compensation to the firm’s performance, rather than project outcome. In addition, traditional structures allow the individual firms to profit by transferring risk and blame to other parties. In this framework, it is more advantageous—at the individual firm level—to blame others for a problem than it is to expend the effort to avoid or solve the problem.

Principles of Integrated Project Delivery

Allison is one of the developers of the American Institute of Architects IPD Guide [1], known as the "bible" of IPD. The guide sets out the following principles to be followed for successful IPD implementation:

- Mutual Respect and Trust: All involved parties-owner, designer, contractor consultants, subcontractors, and suppliers realize the value of collaboration and commit to teamwork in the project's best interest.

- Mutual Benefit and Reward: IPD compensation recognizes and rewards early involvement. Compensation is based on added value, and it rewards positive behaviour, often by providing incentives tied to project goal achievement.

- Collaborative Innovation and Decision Making Innovation: The free exchange of ideas is supported, and ideas are evaluated by merit, not by status or role. Major decisions are weighed by and possible, made by unanimous judgement.

- Early Involvement of Key Participants: Key participants are involved as early as is practical. Decision making improved by the inrush of key participants' expertise, and this shared knowledge is most profound during the projects early stages when informed judgments have the highest impact.

- Early Goal Definition: Project aims are developed and agreed upon early in the process and upheld by all participants, Insights from every participant are valued to support innovation and superior performance.

- Intensified Planning: The point of IPD Isn't to make less of a design effort. but rather to advance design results in order to streamline and shorten the much more costly construction effort.

- Open Communication: Direct and honest communication among team members is fundamental. In a no-blame culture, the goal is to identify and resolve problems rather than assign liability or blame When disputes arise, they are acknowledged as they happen and quickly resolved.

- Appropriate Technology: IPD often relies on cutting edge technologies. Specifying which technologies you will use at the start of the project maximizes interoperability and technologies that support interoperable data exchanges are essential to project support.

- Organization and Leadership: All team members must be committed to the goals and values of the project team. Leadership is given to the most capable team member based on specific situations. Clearly define roles, but keep in mind that creating artificial barriers can tamp down open communication and risk-taking.

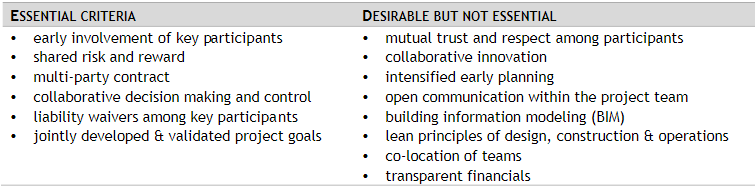

Moreover, Cohen’s report Integrated Project Delivery: Case Studies [4], defined the essential characteristics/ criteria of IPD which shown in table 2 below.

To implement these IPD principles, not only does the concept of differing organizational goals need to be broken, but a system needs to be created where all parties interests and risks are associated with the outcome of that project. Therefore Multi-Party Agreements have been created. The Integrated Project Delivery Agreement (IPDA) is a three-way contract between the owner, the design team and the contractor. Each party’s success is directly tied to the performance of the others. MPA attempts also to increase collaboration even further through a shared “pain/gain” payment structure along with “no blame” contract clauses.

Multi-Party Agreements

[5] According to the AIA Californian Counsel (2007a, p. 32), “In a multi-party agreement (MPA), the primary project participants execute a single contract specifying their respective roles, rights, obligations, and liabilities”. Each party’s contributions and interests are known to everyone. Trust is required as compensations come from project success. Project success is dependent on the participants’ commitment to work together as a team. Integrated teams are creative and flexible, thus making Multi-Party agreements well suited to handle uncertain or complex projects. These type of agreements require team building, thorough planning and negotiation, which needs to take place at an early stage of the project and may be costly. In effect, the multi-party agreement creates a temporary virtual, and in some instances formal, the organization to realize a specific project. Because a single agreement is used, each party understands its role in relationship to the other participants.

Common forms of multi-party agreements include:

- Project Alliances, which create a project structure where the owner guaranteed the direct costs of non-owner parties, but payment of profit, overhead and bonus depends on project outcome.

- Single-Purpose Entity, which is a temporary, but formal, a legal structure created to realize a specific project; and

- Relational Contracts, which are similar to Project Alliances in that a virtual organization is created from individual entities, but it differs in its approach to compensation, risk sharing and decision making.

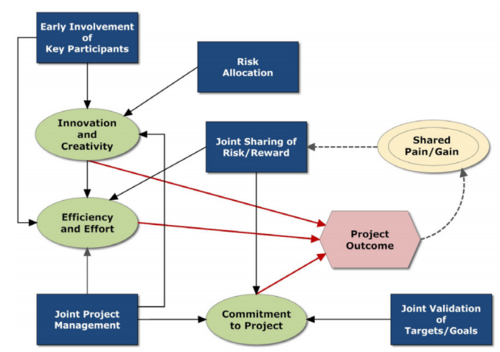

There are many aspects to an IPD agreement, we believe that five factors are particularly important [6]. These factors, shown in the rectangles in Figure 2 have a direct influence on project outcome.

Benefits of IPD

Challenges/ Limitations

Bibliography

- AIA and AIA California Council, “Integrated Project Delivery, A Guide,” 2007,[1]

Document forward: “This Guide provides information and guidance on principles and techniques of integrated project delivery (IPD) and explains how to utilize IPD methodologies in designing and constructing projects. This Guide responds to forces and trends at work in the design and construction industry today. It may set all who believe there is a better way to deliver projects on a path to transform the status quo of fragmented processes yielding outcomes below expectations to a collaborative, value-based process delivering high-outcome results to the entire building team.”

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Integrated Project Delivery: A Guide https://www.aiacontracts.org/resources/64146-integratedproject-delivery-a-guide/ American Institute of Architecture (2007)

- ↑ Haskell-INTEGRATED PROJECT DELIVERY VS. PURE DESIGN-BUILD http://www.haskell.com/media/10651/integrated-project-delivery-vs-pure-db.pdf

- ↑ blah blah blah

- ↑ Cohen, Johnathan (2010) Integrated Project Delivery: Case Studies The American Institute of Architects, California Council in partnership with AIA http://www.aia.org/about/initiatives/AIAB082049 9apr10

- ↑ Ghassemi, R. & Beceric-Gerber, B., (2011). Transitioning to Integrated Project Delivery: Potential barriers and lessons learned

- ↑ Ashcraft. H, & Bridgett-LLP.H (2014).Integrated Project Delivery: Optimizing Project Performance https://www.hansonbridgett.com/~/media/Files/Publications/HA_IPD.pdf