Meeting strategies

(→Project life cycle in phases) |

(→Project life cycle in phases) |

||

| Line 84: | Line 84: | ||

| − | Figure 2 shows a generic, high-level view of how the cost and staffing level evolve across the project life cycle. Cost and staffing level are low at the start, increases when the project is carried out and decreases fast in the closing phase <ref name="PMBOKguide2013" /> | + | Figure 2 shows a generic, high-level view of how the cost and staffing level evolve across the project life cycle. Cost and staffing level are low at the start, increases when the project is carried out and decreases fast in the closing phase. <ref name="PMBOKguide2013" /> |

| − | This indicates that throughout the whole execution phase, knowing how to structure time | + | This indicates that throughout the whole execution phase, knowing how to structure time is of high importance, since many people are involved and costs are at the highest. |

Creating structure and a plan for meeting management early in the project (prior to execution) helps to maintain focus and efficiency when costs are high. | Creating structure and a plan for meeting management early in the project (prior to execution) helps to maintain focus and efficiency when costs are high. | ||

Revision as of 20:41, 26 February 2018

Contents |

Abstract

A meeting is a formal or informal event where individuals meet either face-to-face or virtually (by the use of audio or video conference tools). In projects, groups of people need to discuss, align, inform and communicate other ways, hence there exist numerous purposes and needs for meetings. They are essential for collaboration and decision making in a project and revolve around key project management activities such as cost, scheduling and quality.

Research reveals that even though managers spend more than 50% of their time in meetings, many meetings fail and cause big unnecessary costs and waste of time[1]. Project managers often need to not only participate frequently in meetings, but also plan, facilitate and evaluate meetings throughout the entire project life cycle and especially during the execution phase when project resources most often are at the highest. Project managers can use this as an opportunity to implement strategies for creating and managing effective meetings.

The purpose of this article is to provide strategies in the form of guidelines for project managers to consider and implement in projects. In order to develop an in-dept understanding of challenges with meetings and solutions to these challenges, this article builds on state-of-the-art research and studies on meetings from leading universities and standards on project management from PMI's "A guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge" [2].

The key benefit for a project manager when planning an approach to meetings is that it identifies the approach to communicate most effectively and efficiently, both internal in the project team and with stakeholders. Developing a strategy for meetings can save the project time and costs and on same time keep project team members motivated.

Too many meetings fail

“Meetings are often unnecessary or badly run” claims the authors of “Kill bad meetings”[3]. They support this statement with research from scientific studies and industry research conducted by the authors themselves.

Unnecessary meetings: they’ve found that up to half of the content in meetings is not relevant to participants or could be delivered in other, more simple ways.

Badly run meetings: many meetings that need to happen fails to deliver outcome effectively and do not encourage participation.

When investigating the relevance in this statement, examples from other sources show similar results:

- In a study made by Microsoft 69% of the 38.000 participants felt meetings weren't productive. 60% said they didn't have work-life balance, and the feeling of being unproductive contributed to this[4]

- People spend an average of 2 days per week in meetings and 50% of it is a waste of time[3]

- Too many meetings is the #1 waste of time at the office, with 47% of votes, up from #3 in 2008[3]

The last example points towards that either the quality of meetings is worsening, or that the amount of meetings is increasing. In the study "Collaborative Overload" claims the authors that over the last 20 years the time spent by people in collaborative activities (meetings, calls, emails etc.) has increased by 50% or more [5]

The effect of bad meetings are many and can turn into inhibitors in projects:

- Meetings are huge costs in projects.

Example: a managerial/professional person in Europe or in the USA costs around $100,000 to employ in 2017. $40,000 of this is spent directly on attending meetings. Preparation for meetings is not included to this.[3]. In addition to this, time spent in meetings is also time not spent on individual work – many meetings and interruptions during a day can postpone important tasks for an individual. - People attending meetings perceived as ineffective are affected at the end of the workday and it affects their overall job satisfaction. Employees feel stress, dissatisfied with their jobs and the study reveals that they are more likely to leave their job.[6]

These two reasons can become big challenges for a project manager. Reaching overall goals: deliver projects on time and under budget within scope is threatened and the risk increases when there is no control.

The Causes for bad meetings vary, but general causes include:

- In many project organizations, the whole field of “meetings” is unmanaged.

Who call, run and attend meetings and how often is often not agreed. - Unmanaged meetings generate unmanaged costs.

In the example stated above, more than 40% of one resource’s cost and time is spent on meetings. This leaves less than 60% time to manage/work individually on a project. - Today, projects are becoming more complex within product and service development. Higher complexity often needs people with different specialties and big project organizations. This can also result in more unmanaged meetings. [7]

Project life cycle in phases

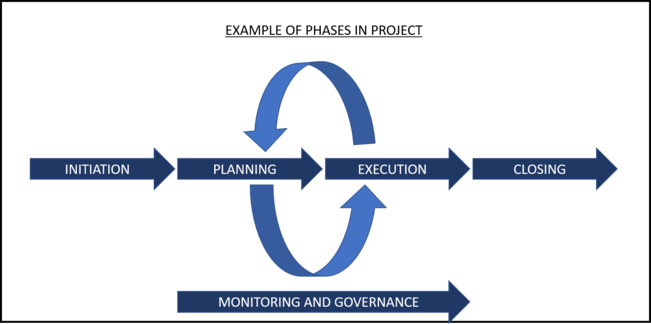

Splitting up a project into phases allows project management to plan and control progress throughout a project life cycle. The partition of projects shows when the load is highest and when it is reasonable to prepare the strategy, in order to succeed with managing meetings.

A project manager will manage meetings throughout the whole project. Some meetings such as a project status meeting or budget meeting can be recurring from beginning to end. Other meetings are only relevant in one phase and some only happen once.

In order to prepare for meetings and assess impact, the manager identifies current challenges in one phase in relation to achieving overall project goal. A useful method for this is to identify project phases.

A project phase consists of related project activities sharing a goal. Completing activities will strive towards reaching the goal and entering next project phase. Project phases can occur iteratively. In some cases, new findings occur in the executing phase which demands project teams to make changes in scope and revisit the planning phase. There is no one-size-fits-all-model to describe project phases in every project. Projects are unique and various industries use various project models. However, most projects go through following four phases with related project management activities: [2]

Initiation

- Definition of new project/new phase of existing project

- Initial scope and finances

- Stakeholders that influence overall outcome will be identified and project manager will be selected

- Project charter/mission statement including business case needs approval to complete this phase

Planning

- Scope is refined and objectives are found

- Project (core) team is established

- PM-plan and plan for project timeline are created

- Shared documents and platforms within project are created including documents about: scope, time, cost, quality, communication, stakeholder engagement, risks, procurement, human resources etc.

- Information related to project is gathered

Execution

- Other project participants might be discovered

- Work defined in plan made in previous phase is performed and completed, unless severe changes are discovered. In this case, there might be a need for an iteration back to the planning phase.

- People and resources are coordinated, stakeholder expectations are managed, activities of project are integrated and performed in accordance with plan.

Results requiring updates and needing to revisiting planning phase include: activities' duration, pricing, unanticipated risks.

Closing

- Completing of project include:

- Closing contracts

- Archive data

- Closeout procurement

- Evaluate and note learnings and reviews.

Project activity in phases

Figure 2 shows a generic, high-level view of how the cost and staffing level evolve across the project life cycle. Cost and staffing level are low at the start, increases when the project is carried out and decreases fast in the closing phase. [2]

This indicates that throughout the whole execution phase, knowing how to structure time is of high importance, since many people are involved and costs are at the highest. Creating structure and a plan for meeting management early in the project (prior to execution) helps to maintain focus and efficiency when costs are high.

Meeting strategies

Successful communication in a project underpins accurate message deliveries, sufficient communication to stakeholders, higher level of employee involvement and the ultimate success of any project.

In most projects, planning communication occurs early in the planning phase and can be included in the project management plan. This allows the manager to appropriately consider resources, such as time and costs in communication activities.

Listed below are suggestions for meeting strategies for the project manager to consider. Research relies on several scientific studies.

Avoiding unnecessary meetings with effective communication

In projects, effective communication is when information is provided in right format, at the right time, to the right audience, and with the right impact. [2] Setting up guidelines in projects for when it is ok to invite to a meeting is one strategy to avoid the meetings not creating value in projects. Indicators for when there is a need for a meeting are listed here:

- when unresolved issues are inhibiting the progress of a project or interdependent projects.[6]

- a big decision needs to be made

- idea generation

- a compelling agenda is distributed prior to the meeting

- celebration of reaching a milestone

In other cases, communication is needed but not in meetings. This can often be identified as the type of communication where only one person needs to speak. Examples are:

- Updates

- Delivery of information

- Presentations

All the above can often be delivered in an email, via a phone call or in an informal meeting with only two people. Information can often be found in existing repositories (reports/internal knowledge sharing portals). When a person chooses to invite other(s) to a meeting to deliver information they could have found themselves, the meeting becomes costly mismanaged time for all involved. This is an example of one bad effect, when meetings aren’t managed.

In some projects, meeting free days are introduced where participants have to reject meetings occurring on their meeting free day. In other projects it is allowed for participants to select amongst meetings to attend. When selecting, a small checklist similar to figure 3 can be used (MANGLER FIGUR)

Creating valuable meetings

Being the creator of a meeting means that one needs to determine who needs to participate and how to keep participants interested and involved during a meeting. Following is a checklist for the meeting creators. Answering these questions gives an overview and frames the purpose of the meeting.

- Who do I need?

- Why do we need to meet?

- Be specific(???)

- What is the outcome?

Segment between core group and peripheral project members: only involve last part when their input is very critical.

Planning meetings in advance to maximize efficiency

In projects, efficient communication means providing only the information that is needed[2].

It is agreed in literature used in this article[6][2][3][8] that creating a compelling agenda and sending relevant material to meeting participants is a time saving action. In some cases, the agenda shows time estimates for the different topics. This gives participants an understanding of the important tasks in the meeting and signals when there is time for discussion and when there is not. An agenda also helps participants to know if they need to join the meeting or not. The agenda needs to be relatable. Topics like: “business review” does not fall into this category and can either be elaborated or phrased differently.

The purpose of the agenda is to give meeting participants an introduction to the meeting, then they know if their participation is needed and how to prepare. To avoid the meeting from becoming a habit, the agenda can include supporting information. Sending out agenda prior to meeting allows participants to contribute, which makes the contemporary agenda relevant.

Participation during meeting

Often when people give meetings bad reviews, it is because the meeting doesn’t seem relevant to them. People are motivated, when purpose/success criteria relates to their role and tasks in a project. Having an important role during the meeting creates purpose for them to participate, therefore encouraging active participation, delegating actions before, during or after meeting will encourage participants.

Meeting techniques and locations

Previously, creating a compelling agenda was recommended. It is just as important to know how to use the agenda. In some cases, derivatives from the topics on the agenda can be the most valuable part of the meeting. Participants are engaged and new solutions/organizational knowledge is created. In order to do this and still manage a valuable meeting, the manager’s focus need to be on the output rather than sticking to the agenda. Hall[3] suggests following five questions:

- What outcome do we want from this topic?

- What process will we need to deliver this outcome?

- Which participants need to be involved?

- How much time is worth spending on this?

- To avoid meetings from becoming a habit?

( MANGLER Purpose model from PMBOK??)

Rogelberg[6] suggests to experiment with new techniques and locations in order to stimulate participation and ideas. For meetings including many people and where decision making is important, it is sometimes helpful to split the crowd up in smaller groups. Similarly, holding meetings standing up or in new environments often helps creativity and breaking up habits.

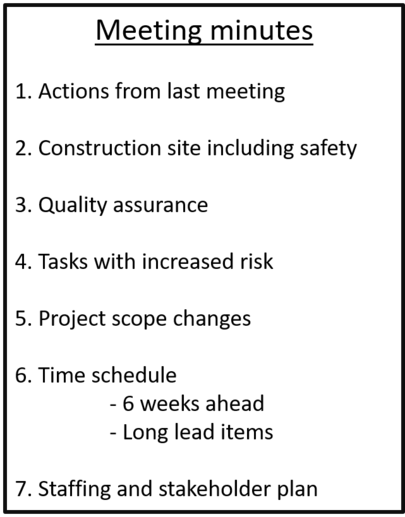

Meeting minutes as a strategic tool

Important information and actions from meetings are often stored in minutes and saved in the project management plan(PMIBOK). Information kept in minutes should follow a structure and be maintained in an organized manner. Minutes can also be used strategically as a “meeting timeline”. For recurring, weekly meetings, such as a project status meeting or steering committee meeting, minutes from the previous week including important concerns, questions and actions can be used as an outcome driven agenda (ref: industry).

See figure 5 as an industry example.

Monitor effects

There are several ways to monitor how the application of meeting strategies affects the project’s progress. A few are listed below.

- Survey core group: an open survey with room for respondents to suggest their improvements.

- KPI: Key performance indicators can either measure progress or achievement of operational goal. For monitoring meeting the success of strategies suggested in this article, relevant KPI’s are stakeholder satisfaction (for stakeholder meetings),

project profitability (difference between revenue generated by a project and cost of delivering work), project success rate (percentage of projects delivered on time and under budget)

- Pulse-checks: informal, focused conversations with employees to understand how they approach their work.

Meetings as a basis for change

As previously stated, meeting culture can have a great impact in a project and in organizations. If succeeding with strategizing meetings in one project, the application in other projects or programs can be considered. A goal for changing meetings is to create new organizational culture with improved communication, productivity and integration of the work. Increased job satisfaction and work/life balance is another perk, therefore, better meetings – better work lives[8]

Implementation of protocols and changing behaviors take time. Sustaining momentum is an even bigger challenge and can often not be considered as a process but more likely an ongoing activity needing consistent attention. However, if successful there is no reason for the meeting strategy not to scale up and become a supporting act to the organizational strategy.

Limitations

There are several limitations to strategies suggested as meetings vary a lot in different organizations, even within different projects. However, this article deals with well known, generic problems and challenges. Limitations are following:

- Having too many meetings can be a symptom of a deeper, underlying corporate and cultural beliefs and practices. Therefore, reducing the number of meetings and sorting meetings in relevance may not improve working conditions for the team. Instead

there is a chance that another activity will fill in the empty time slot. Too many meetings can be the tip of the iceberg of deeper underlying challenges in an organization, the action of sorting in meetings itself will not resolve this. - Working with changing meetings can be costly itself. It may not be suitable for all companies, because the revenue created is not directly to view on the bottom-line. At least not in the beginning.

- Changing meeting culture is a team effort. One manager cannot perform severe changes without encouragement from team and upper management.

Annotated bibliography

Project Management Institute. "A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide)". Fifth edition, 2013.[2]

The concept of dividing a project’s life cycle into phases is described in PMBOK as well is the project communications management. Chapter 10 illustrates how communication is planned, distributed and documented. The book contains an in-depth walk through challenges, guidelines and tools useful in project management industry.

Rogelberg, S., Scott, C. Kello, J. “The Science and Fiction of Meetings” 2007[6]

This article evolve around employees spending an increasing amount of time in meetings and also complaining about them. But these employees see meetings as a tool for productivity and there is a need for companies learning to use this tool (meetings) better. The article provides examples and has statistics over how much time is spent in meetings.

Hall, K., Hall, A. "Kill Bad Meetings" 2017[3]

The book is based on industry research as well as the authors own experiences as former CEOs in big organizations. The book aims to improve meeting culture worldwide by providing tools for managers to introduce in their own project and/or organization. The book also covers cross cultural meetings, dealing with different time zones as well as facilitating a conference: a meeting for a lot of people.

References

- ↑ Romanco, N. and Nunamaker, J. (2001). Meeting Analysis: Findings from Research and Practice. Proceedings of the 34th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Science, p 4. Available at: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.570.6650&rep=rep1&type=pdf [Accessed 19 Feb. 2018]

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Project Management Institute. (2013). A guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® guide)- Fifth Edition, Pennsylvania: Project Management Institute, Inc., p.589

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 Hall, K. and Hall, A. (2017). Kill Bad Meetings. London: NB Books, p. 224.

- ↑ Microsoft.com. (2005). Survey finds workers average only three productive days per week. Available at: https://news.microsoft.com/2005/03/15/survey-finds-workers-average-only-three-productive-days-per-week/ [Accessed 29 Jan. 2018]

- ↑ Cross, R., Rebele, R., Grant, A. (2016). Collaborative Overload. Harvard Business Review, January-February 2016, p. 74-79. Available at: https://hbr.org/2016/01/collaborative-overload [Accessed 19 Feb, 2018]

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Rogelberg, S., Scott, C. Kello, J. (2007). The Science and Fiction of Meetings. MIT Sloan Management Review, Volume 48(2), p. 18-21. Available at: https://orgscience.uncc.edu/sites/orgscience.uncc.edu/files/media/Rogelberg%20et%20al.%20-%202007%20-%20The%20science%20and%20fiction%20of%20meetings.pdf [Accessed 19 Feb, 2018]

- ↑ Weck, O., Roos, D., Magee, C. (2011). Engineering Systems: meeting human needs in a complex technological world. Cambridge, Masssachusetts: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, p. 208.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Perlow, L., Hadley, C., Eun, E. (2017). Stop the Meeting Madness. Harvard Business Review, July-August 2017, p. 62-69. Available at: https://hbr.org/2017/07/stop-the-meeting-madness [Accessed 23 Feb, 2018]