Mindfulness and Cognitive Biases in Project Management

MistaJacob (Talk | contribs) |

MistaJacob (Talk | contribs) (→The Two Ways of Thinking) |

||

| Line 39: | Line 39: | ||

<div><ul> | <div><ul> | ||

| − | <li style="display: inline-block;"> [[File:Fear.jpg|thumb|none| | + | <li style="display: inline-block;"> [[File:Fear.jpg|thumb|none|280px|''Source:'' <ref>[http://cdn.theatlantic.com/assets/media/img/posts/2015/02/7_Set_Fear/acc39d207.jpg Facial expression: fear]</ref>]] </li> |

</ul></div> | </ul></div> | ||

| − | Many things simultaneously happened here. Just as easy as you noticed that the man's hair is black on the top and grey on the sides, you knew that he was scared. What further came to mind was probably thoughts about what he is looking at. If measured, it is also likely that your heart rate increased. You did not intend to assess his mood, or identify possible reasons for why he got this frightened, it just happened to you. It was an instance of fast thinking<ref name= | + | Many things simultaneously happened here. Just as easy as you noticed that the man's hair is black on the top and grey on the sides, you knew that he was scared. What further came to mind was probably thoughts about what he is looking at. If measured, it is also likely that your heart rate increased. You did not intend to assess his mood, or identify possible reasons for why he got this frightened, it just happened to you. It was an instance of fast thinking<ref name="k">Kahneman, Daniel. ''Thinking, Fast and Slow''. N.p.: Penguin, 2011. Print. - '''Annotation:''' A review of how the human mind works, with focus on the division between two ways of thinking, fast and slow. It explains the origin of many cognitive biases, and is therefore an essential piece of literature to this article.</ref>. |

| + | |||

Now consider the following math problem. | Now consider the following math problem. | ||

| Line 48: | Line 49: | ||

::::::::::::::::::: 13 x 27 | ::::::::::::::::::: 13 x 27 | ||

| − | You recognized immediately that this is a multiplication problem. You might also have had the feeling that you would be able to solve it, if given some time. If asked whether the answer could be 57 or 3200, you would fast and intuitively know that this was not the case. On the other hand, if asked the same with 332, a fast and intuitive acceptance or rejection would probably not come to mind. To solve it, you would have to slow down your thinking, try to recall the rules of multiplication you learned in school, and apply them. Either if you solved it, or gave up (the answer is 351), this was a deliberate mental process that required effort and attention. You just experienced a prototype of slow thinking<ref name= | + | You recognized immediately that this is a multiplication problem. You might also have had the feeling that you would be able to solve it, if given some time. If asked whether the answer could be 57 or 3200, you would fast and intuitively know that this was not the case. On the other hand, if asked the same with 332, a fast and intuitive acceptance or rejection would probably not come to mind. To solve it, you would have to slow down your thinking, try to recall the rules of multiplication you learned in school, and apply them. Either if you solved it, or gave up (the answer is 351), this was a deliberate mental process that required effort and attention. You just experienced a prototype of slow thinking<ref name="k" />. |

| − | Psychologists have for decades been interested in the two ways of thinking, fast and slow. Keith Stanovich and Richard West defined the terms System 1 and System 2 for respectively fast and slow thinking<ref name= | + | Psychologists have for decades been interested in the two ways of thinking, fast and slow. Keith Stanovich and Richard West defined the terms System 1 and System 2 for respectively fast and slow thinking<ref name="k" />, which will be used onwards, and described further in the sections below. |

==System 1== | ==System 1== | ||

System 1 operates | System 1 operates | ||

Revision as of 20:44, 27 September 2015

This article will address how knowledge about, mindfulness, the workings of the mind, and the related cognitive biases that follows; can be used as tools to better deal with high-risk decisions in an inherently dynamic and complex world.

The focus will be in the area of “project, program, and portfolio management”, that for the ease of reading, only will be denoted as “project management” in the remainder of the article.

Before introducing the concepts of mindfulness and cognitive biases, a short introduction to complexity and the thinking behind “engineering systems” is necessary, as to explain their relevance and usefulness.

Contents |

Complexity

Even among scientists, there is no unique definition of Complexity[1]. Instead, real-world systems of what scientist believe to be complex, have been used to define complexity in a variety of different ways, according to the respective scientific fields. Here, a system-oriented perspective on complexity is adopted in accordance to the definition in [2], which list the properties of complexity to be:

- Containing multiple parts;

- Possessing a number of connections between the parts;

- Exhibiting dynamic interactions between the parts; and,

- The behaviour produced as a result of those interactions cannot be explained as the simple sum of the parts (emergent behaviour)

In other words, a system contains a number of parts that can be connected in different ways. The parts can vary in type as well as the connections between them can. The number and types of parts and the number and types of the connections between them, determines the complexity of the system. Furthermore, incorporating a dynamic understanding of systems, both the parts and their connections changes over time. The social intricacy of human behaviour are one of the more significant reasons for this change. We do not always behave rationally and predictably, as will be further examined below, which increases the complexity of every system where humans are involved.

Engineering systems

The view that our modern lives are governed by engineering systems, articulated by de Weck et al.[4], are adopted to explain why the complexity of the world only goes one way, upwards. In short, they distinguish between three levels of systems; artifact, complex, and engineering. See Figure 1 for a visual representation of the following example. At artifact level we have inventions, e.g. cars, phones, the light bulb, etc. In itself, they do not offer any real benefits to our lives. To utilize their potential, and to exploit their respective benefits, the right infrastructure has to be present. Continuing the above example, the needed infrastructure consists of; roads, public switched telephone network (PSTN), and the electrical power grid. This level of interconnectedness are defined as the complex system level. Continuing further; the once separated transportation, communication, and energy system, is now getting increasingly interconnected. This is the engineering systems level.

One of the characteristics of our modern society and the engineering systems governing it, is that technology and humans cannot any longer be separated. Engineering systems are per definition socio-technical systems, which as described in the section above, only adds to the complexity. Without the right tools to analyse and understand them, complex systems become complicated: They confuse us, and we cannot control what happens or understand why[5]. Mindfulness and knowledge about cognitive biases are some of those tools that can be adopted to project management to help decomplicate the complexity.

Mindfulness

Mindfulness is defined as[6]: The quality or state of being conscious or aware of something. Weick & Sutcliffe further elaborated the definition[7]: a rich awareness of discriminatory detail. By that we mean that when people act, they are aware of context, of ways in which details differ (in other words, they discriminate among details), and of deviations from their expectations. Put in another way, the mindful project manager knows that simplicity is not a word suited to describe the world around us; and that even the smallest deviation from the expected can be symptoms of larger problems. To translate this mindset into a useful model, Weick & Sutcliffe[8] developed five principles of mindfulness, that could be used to increase the reliability of organizations. In other words, to enhance both the chance that an organization can prevent possibly disastrous unexpected events, as well as making a rapid recovery if they do happen. These principles are therefore well suited to deal with the intrinsic uncertainty of human behaviour and the complexity it brings to organizations. The principles are:

- Reluctance to simplicity

- Preoccupation with failure

- Sensitivity to operations

- Commitment to resilience

- Deference to expertise (collective mindfulness)

Describing the principles further is outside the scope of this article, but additional information can be found at: Organisational Resilience with Mindfulness, as well as Oehmen et al.[9]. The latter have adapted these principles to the field of project management, and in their description of “Sensitivity to operations”, they wrote: Be responsive to the messy reality inside of projects. This involves, on the one hand, ... , and on the other, being mindful to the potential unexpected events that go beyond what one would usually control in the project context. The “thing” that goes beyond what one would usually control, is in this context chosen to be our own mind. It is well known that cognitive biases exist, and that the deviousness of the mind can constitute a risk to any project. But how can we discipline our mind to think sharper and clearer? How can we make sure that our rational decisions are in fact rational? And, are some people more predispositioned to get caught by cognitive biases than others? Answering these questions will be the focus of the remainder of the article, where you will be guided through some of the workings of your mind.

Before Reading On

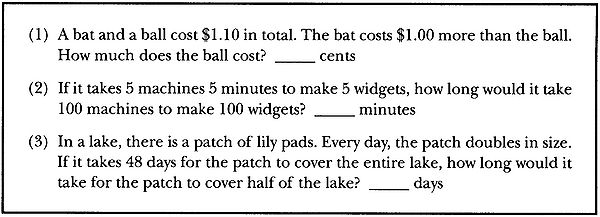

Please take a quick look at the following 3 questions, and provide an initial answer to them before reading on.

-

Source: [10]

Source: [10]

The Two Ways of Thinking

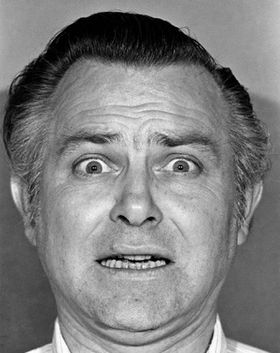

To observe your mind in automatic mode, take look at Figure 2.

-

Source: [11]

Source: [11]

Many things simultaneously happened here. Just as easy as you noticed that the man's hair is black on the top and grey on the sides, you knew that he was scared. What further came to mind was probably thoughts about what he is looking at. If measured, it is also likely that your heart rate increased. You did not intend to assess his mood, or identify possible reasons for why he got this frightened, it just happened to you. It was an instance of fast thinking[12].

Now consider the following math problem.

- 13 x 27

You recognized immediately that this is a multiplication problem. You might also have had the feeling that you would be able to solve it, if given some time. If asked whether the answer could be 57 or 3200, you would fast and intuitively know that this was not the case. On the other hand, if asked the same with 332, a fast and intuitive acceptance or rejection would probably not come to mind. To solve it, you would have to slow down your thinking, try to recall the rules of multiplication you learned in school, and apply them. Either if you solved it, or gave up (the answer is 351), this was a deliberate mental process that required effort and attention. You just experienced a prototype of slow thinking[12]. Psychologists have for decades been interested in the two ways of thinking, fast and slow. Keith Stanovich and Richard West defined the terms System 1 and System 2 for respectively fast and slow thinking[12], which will be used onwards, and described further in the sections below.

System 1

System 1 operates

Annotated Bibliography

- ↑ Johnson, N. F. (2007). Two's company, three is complexity: A simple guide to the science of all sciences, ch. 1, London, England: Oneworld Publications Ltd. - Annotation: Chapter 1 explains how complexity can be understood, and goes through some of its key components. Here, only the beginning of the chapter was used to explain that no absolute definition of complexity exists.

- ↑ Oehmen, J., Thuesen, C., Ruiz, P. P., Geraldi, J., (2015). Complexity Management for Projects, Programmes, and Portfolios: An Engineering Systems Perspective. PMI, White Paper. - Annotation: A review of the contemporary movements within the area of project, program, and portfolio management. Its definition of complexity, the section about mindfulness, and its mention of cognitive biases, was an essential first step in the shaping of the content of this article.

- ↑ (de Weck et al.,2011, p. 14)

- ↑ de Weck, O. L., Roos, D., & Magee, C. L. (2011). Engineering systems: Meeting human needs in a complex technological world, ch. 1 & 2. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. - Annotation: The first two chapters of the book is about how the human inventions begin to be connected, create networks and infrastructure, along with some of the complications on the way. It defines how we went from simple inventions, through complex systems, to engineering systems where everything is interconnected. This view was adopted here as a help to explain why the complexity of the world only is on the rise, and that new tools are required to deal with it.

- ↑ (Oehmen et al., 2015, p. 5)

- ↑ Definition of Mindfulness in English: Mindfulness. N.p., n.d. Web. 27 Sept. 2015. <http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/mindfulness>

- ↑ (Weick & Sutcliffe, 2001, p. 32)

- ↑ Weick, K. E., & Sutcliffe, K. M., (2001). Managing the unexpected: Assuring high performance in an age of complexity. San Francisco, CA: Wiley. - Annotation: Cited through (Oehmen et al., 2015)

- ↑ (Oehmen et al. (2015, p. 27-28)

- ↑ Shane, F., Vol. 19, No. 4 (Autumn, 2005), Cognitive Reflection and Decision Making, p. 27. American Economic Association, The Journal of Economic Perspectives

- ↑ Facial expression: fear

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Kahneman, Daniel. Thinking, Fast and Slow. N.p.: Penguin, 2011. Print. - Annotation: A review of how the human mind works, with focus on the division between two ways of thinking, fast and slow. It explains the origin of many cognitive biases, and is therefore an essential piece of literature to this article.