Mindfulness and Cognitive Biases in Project Management

Developed by Martin Jacobsen

This article will address how knowledge about, mindfulness, the workings of the mind, and the related cognitive biases that follows; can be used as tools to better deal with high-risk decisions in an inherently dynamic and complex world.

The focus will be in the area of “project, program, and portfolio management”, that for the ease of reading, only will be denoted “project management” in the remainder of the article.

Before introducing the concepts of mindfulness and cognitive biases, a short introduction to complexity and the thinking behind “engineering systems” is necessary, as to explain their relevance and usefulness.

Contents |

Complexity

Even among scientists, there is no unique definition of Complexity.[1] Instead, real-world systems of what scientist believe to be complex, have been used to define complexity in a variety of different ways, according to the respective scientific fields. Here, a system-oriented perspective on complexity is adopted in accordance to the definition in Oehmen et al.,[2] which list the properties of complexity to be:

- Containing multiple parts;

- Possessing a number of connections between the parts;

- Exhibiting dynamic interactions between the parts; and,

- The behaviour produced as a result of those interactions cannot be explained as the simple sum of the parts (emergent behaviour)

In other words, a system contains a number of parts that can be connected in different ways. The parts can vary in type as well as the connections between them can. The number and types of parts and the number and types of the connections between them, determines the complexity of the system. Furthermore, incorporating a dynamic understanding of systems, both the parts and their connections changes over time. The social intricacy of human behaviour is one of the more significant reasons for this change. We do not always behave rationally and predictably, as will be further examined below, which increases the complexity of every system where humans are involved.

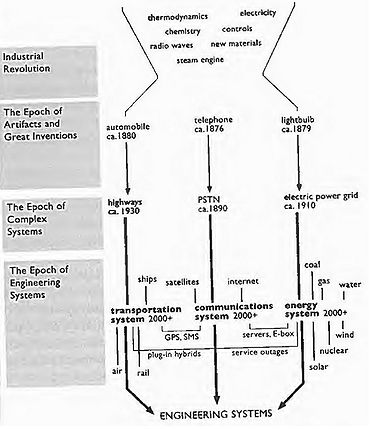

Engineering systems

The view that our modern lives are governed by engineering systems, articulated by de Weck et al.,[4] is adopted to explain why the complexity of the world only goes one way, upwards. In short, they distinguish between three levels of systems: artifact, complex, and engineering. See Figure 1 for a visual representation of the following example. At artifact level we have inventions, e.g. cars, phones, the light bulb, etc. In themselves, they do not offer any real benefits to our lives. To utilize their potential, and to exploit their respective benefits, the right infrastructure has to be present. Continuing the above example, the needed infrastructure consists of: roads, public switched telephone network (PSTN), and the electrical power grid. This level of interconnectedness is defined as the complex systems level. Continuing further; the once isolated transportation, communication, and energy system, is now getting increasingly interconnected. This is the engineering systems level.

One of the characteristics of our modern society and the engineering systems governing it, is that humans and technology cannot any longer be separated. Engineering systems are per definition socio-technical systems, which as described in the section above, only adds to the complexity. Without the right tools to analyse and understand them, complex systems become complicated: They confuse us, and we cannot control what happens or understand why.[5] Mindfulness and knowledge about cognitive biases are some of those tools that can be adopted to project management to help decomplicate the complexity.

Mindfulness

Mindfulness is defined as:[6] the quality or state of being conscious or aware of something. Weick & Sutcliffe further elaborated the definition:[7] a rich awareness of discriminatory detail. By that we mean that when people act, they are aware of context, of ways in which details differ (in other words, they discriminate among details), and of deviations from their expectations. Put in another way, the mindful project manager knows that simplicity is not a word suited to describe the world around us; and that even the smallest deviation from the expected can be symptoms of larger problems. To translate this mindset into a useful model, Weick & Sutcliffe[8] developed five principles of mindfulness, that could be used to increase the reliability of organizations. In other words, to enhance both the chance that an organization can prevent possibly disastrous unexpected events, as well as making a rapid recovery if they do happen. These principles are therefore well suited to deal with the intrinsic uncertainty of human behaviour and the complexity it brings to organizations. The principles are:

- Reluctance to simplicity

- Preoccupation with failure

- Sensitivity to operations

- Commitment to resilience

- Deference to expertise (collective mindfulness)

Describing the principles further is outside the scope of this article, but additional information can be found at: Organisational Resilience with Mindfulness, as well as in Oehmen et al.[9] The latter have adapted these principles to the field of project management, and in the description of “Sensitivity to operations”, they wrote: Be responsive to the messy reality inside of projects. This involves, on the one hand, ... , and on the other, being mindful to the potential unexpected events that go beyond what one would usually control in the project context. The “thing” that goes beyond what one would usually control, is in this context chosen to be our own mind. It is well known that cognitive biases exist, and that the deviousness of the mind can constitute a risk to any project. But how can we discipline our mind to think sharper and clearer? How can we make sure that our rational decisions are in fact rational? And, are some people more predispositioned to get caught by cognitive biases than others? Answering these questions will be the focus of the remainder of the article, where you, “the reader”, will be guided through some of the workings of your mind.

Before Reading On

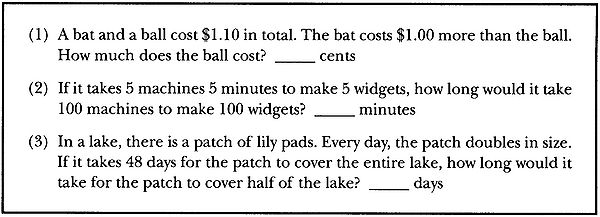

Please take a quick look at the following 3 questions, and provide an initial answer to them before reading on.

-

Source: [10]

Source: [10]

The Two Ways of Thinking

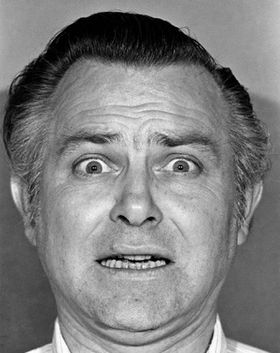

To observe your mind in automatic mode, take look at Figure 2.

-

Figure 2: Source: [11]

Figure 2: Source: [11]

Many things simultaneously happened here. Just as easy as you noticed that the man's hair is black on the top and grey on the sides, you knew that he was scared. What further came to mind was probably thoughts about what he is looking at. If measured, it is also likely that your heart rate increased. You did not intend to assess his mood, or identify possible reasons for why he got this frightened, it just happened to you. It was an instance of fast thinking[12].

Now consider the following math problem, and try to solve it.

- 13 x 27

You recognized immediately that this is a multiplication problem. You might also have had the feeling that you would be able to solve it, if given some time. If asked whether the answer could be 57 or 3200, you would fast and intuitively know that this was not the case. On the other hand, if asked the same with 332, a fast and intuitive acceptance or rejection would probably not come to mind. To solve it, you would have to slow down your thinking, try to recall the rules of multiplication you learned in school, and apply them. Either if you solved it, or gave up (the answer is 351), this was a deliberate mental process that required effort and attention. You just experienced a prototype of slow thinking.[12]

Psychologists have for decades been interested in the two ways of thinking, fast and slow. Keith Stanovich and Richard West defined the terms System 1 and System 2 for respectively fast and slow thinking,[12] which will be used onwards, and described further in the sections below.

System 1

System 1 operates quickly and automatically, with little or no effort, and with no sense of voluntary control. We are born prepared to observe and perceive the world around us, orient attention, recognize objects, and avoid losses.[12] This is an innate skill humans share with other animals. As we observe the world around us, System 1 automatically assesses the new information according to the mental model of the world already created from previous experiences. If something differs, our mental model evolves, and is continuously updated according to the new information. Putting your hand into the flame of a candle, hurts. That information is stored, and accessed without intention and effort,[12] which will probably result in you not doing it again. Other activities become fast and automatic through prolonged practice, e.g. how to gear-shift when driving a car, or understanding nuances of social interaction.

Below is a list of some examples of automatic activities attributed to System 1, as well as a list of some of its limitations:[12]

- Answer the question 2 + 2 = ?

- Detect that one object is more distant than another.

- Orient to the source of a sudden sound.

- Reading simple words (in a language you understand; and, if learned to read)

- Understand simple sentences.

- E.g. “Try not to think of an apple”.

- Recognize common facial expressions.

- Associate “capital of France” with “Paris” (for most people).

Limitations:

- It cannot be turned off.

- Has little understanding of logic and statistics.

- Gullible and biased to believe and confirm.

- Generates a (too) coherent model of the world.

- Focuses on existing evidence and ignores absent evidence (WYSIATI).∗

- Exaggerates emotional consistency (halo effect).∗

- Computes more than intended (mental shotgun).∗∗

∗Links for additional information will be provided further down.

∗∗Will be explained later.

System 2

System 2 is the conscious, reasoning self. It allocates attention to effortful mental activities, like the multiplication problem above; makes choices; decides what to think about and what to do; along with having the ability (which System 1 does not) to construct thoughts in an orderly series of steps.[12] It is also in charge of doubting and logical reasoning.

Below is a list of some of the activities attributed to System 2:[12]

- Check the validity of a complex argument.

- Brace for the starter gun in a race.

- Look for a man with grey hair.

- Focus attention on the passes of the ball in a basketball game.

- Maintain a faster walking speed than is natural for you.

- Focus on the voice of a particular person in a crowded and noisy room.

- Compare two cars for overall value.

The highly diverse operations of System 2 have one thing in common: they all require attention and effort. We all have a limited budget of attention, and if adequate attention is not given to a specific activity, you will perform less well, or simply not be able to perform the activity at all.[12] This is why the phrase “pay attention” is apt. Said in another way, when your budget of attention is used, you are effectively blind to anything else. A great demonstration of this, is The Invisible Gorilla.[13] In short, participants were shown a video of a basketball court where two teams were passing the ball to their teammates. One team with white shirts and the other with black. Before the video started the participants were told to count the number of passes made by the white team, ignoring the black players. During the video a woman in a gorilla suit appears for 9 seconds before moving on. Of the many thousands of people that participated, only about half noticed anything unusual. This illustrates two important facts of the mind. We can be blind to the obvious, and we are blind to our blindness.

Besides the limited budget of attention, System 2 has another limitation, which is that effortful activities interfere with one another.[12] This is the reason you should not try to calculate 13 x 27, while making a right turn in your car crossing a busy bike lane; or why you automatically stops your conversation with the passenger in the car, when a dangerous situation occurs in the traffic.

Below is a list of some of the limitations of System 2:

- Requires effort and attention to work.

- Has a limited budget of attention to allocate.

- When your budget of attention is used, you are effectively blind to anything else.

- Effortful activities interferes with each other.

- Has low efficiency (slow thinking).

- Generally lazy, following the rule of least effort.

Interactions Between the Two Systems

When we are awake, both systems are running simultaneously. System 1 runs automatically and System 2 is normally running in a low-effort mode, in which only a small part of its capacity is used. As described above, System 1 is continuously using its model of the world to assess incoming information. It generates suggestions for System 2: impressions, intuitions, intentions, and feelings. If endorsed by System 2, impressions and intuitions turn into beliefs, and impulses turn into voluntary actions.[14] Most of the time this process runs smoothly, and System 2 believes and adopts these suggestions and acts on them, which is fine - usually.

When System 1 runs into situations where no apparent answer comes intuitively to mind, it calls to System 2 for help. This is what you experienced with 13 x 27. Other situations where the two systems works well together, are when System 1 gets surprised. When it observes something that does not fit with its model of the world, System 2 is activated to search through your memory to make sense of it. This would happen if you saw a flying car, heard a cat bark, or saw a gorilla walk across a basketball court. System 2 also continuously monitor and controls your own behaviour,[12] which e.g. comes in handy when System 1 sends impulses to System 2, that if acted upon, would result in behaviour that is not socially acceptable; like always saying the first thing that comes to mind. In other words, System 2 has the power to overrule the freewheeling impulses, intuitions, and feelings of System 1.

This division of labour is highly efficient. It minimizes effort, and optimizes performance.[12] In general, this constellation works well because System 1 is very good at what it does. Its model of the world is usually accurate; and its short-term predictions of the future, and the suggestions for System 2 that follows, are ordinarily appropriate. As we shall see though, System 1 has biases, and is prone to systematic errors in specific circumstances.

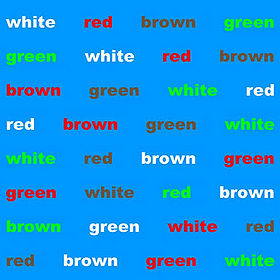

Conflict and Illusions

Figure 3 is a variant of many similar experiments that induces conflict between System 1 and System 2. Before reading on, try to say (out loud, or whispering) the colour of the words.

-

Figure 3: Conflict between System 1 and 2. Source: Say the colour of the words

Figure 3: Conflict between System 1 and 2. Source: Say the colour of the words

The task itself is a conscious logical task solvable by “programming” System 2 to look for, and say the colour of the words. System 1 however, interferes. Recall from earlier that it cannot be turned off, and that you cannot refrain from reading and understanding simple words. It happens automatically, without conscious control, and is the reason for the conflict.[12] This is the effect of the “mental shotgun” mentioned above; we computes more than intended.

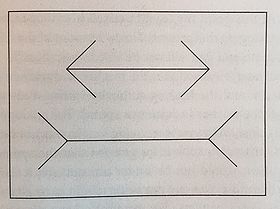

Now, have a look at Figure 4.

- Figure 4: Müller-Lyer. Source: [15]

At a first glance, nothing abnormal is apparent about this picture. We all see that the bottom horizontal line is longer than the one above, and we believe what we see. This, however, is the Müller-Lyer illusion, and measurements will confirm that they are equally long. The remarkable thing is that even now, when System 2 is aware of this fact, we still see the lines as having different length.

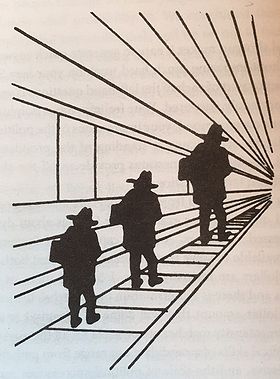

A similar illusion is present at Figure 5, where you are asked: as shown on the screen, is the figure on the right larger than the figure on the left?

- Figure 5: 3-D illusion. Source: [16]

The obvious and intuitive answer, yes; is wrong. They are of equal size. Remember from above that one of the automatic functions of System 1 is to detect whether one object is more distant than another. Even though we are looking at a picture on a flat 2-D screen, System 1 interprets it as a 3-D scene, and sees the right figure as larger. Again, even after we know this, we still get tricked by System 1.

Is Prevention Possible?

Visual illusions as the ones shown above are not the only way to get tricked. Illusions of thought - cognitive illusions - also exists, where the emphasis here is your thoughts and feelings getting tricked.[12] Knowing that these illusions exist, what can we do to overcome them?

Since System 1 cannot be turned off, errors of intuitive thought are difficult to prevent. Firstly, because System 2 may not be aware of the error happening. Secondly, if it did, it would require System 2 to step in an overrule System 1, which requires effort and attention that may not be available in our limited budget. Constantly monitoring and evaluating every suggestion from System 1 would be an impractical and straining way to live, due to the slow and inefficient workings of System 2. As Kahneman[17] puts it: the best we can do is a compromise: learn to recognize situations in which mistakes are likely and try harder to avoid significant mistakes when the stakes are high. In other words; familiarize yourself with the most common and powerful cognitive biases, so you have a chance of preventing their effect when the stakes are high; e.g. when a project manager continuously is facing high-risk decisions in a complex dynamic project.

The Cognitive Reflection Test

One thing is to train/”program” System 2 to become aware of, and react when cues of cognitive biases are present. Another is to figure out whether you are more predispositioned to get caught by cognitive biases than others. To investigate this, Shane Frederick constructed the cognitive reflection test. This test consists of three questions that all have intuitive answers that are both compelling and wrong. It starts with “the bat and ball”-problem, and is the test you took above. Frederick’s found that people that scores low in this test, or tests with a similar type of questions, are more prone to trust the first idea that comes to mind. Put in another way, the supervisory function of System 2 is weak or lazy in these people; meaning that they are unwilling to invest the effort needed to validate their intuition; and are therefore also more susceptible to blindly follow other suggestions from System 1.[12] This “weak supervisory function of System 2” is also known as “lazy thinking”. Following quote sums up the essential:

System 1 is impulsive and intuitive; System 2 is capable of reasoning, and it is cautious, but at least for some people it is also lazy. We recognize related differences among individuals: some people are more like their System 2; others are closer to their System 1. This simple test has emerged as one of the better predictors of lazy thinking.[18]

So to figure out whether you are more predispositioned to get caught by cognitive biases than others; compare your test results with the correct answers below, and ask yourself this: are you more like your System 1 or your System 2?

The correct answers are: 5 cents, 5 minutes, and 47 days.

Further Readings

Continuing the description of some of the more important workings of the mind, that are the origin of many cognitive biases; as well as going through the most common and powerful of these biases, would be a natural next step. This is however outside the scope of this article.

Among those important workings and biases, the author recommends you to seek information about the following:

- Associative memory (related to priming effects, the mental shotgun, etc.).

- Priming effects.

- The halo effect.

- What You See Is All There Is (WYSIATI).

- Which explains, among many others: overconfidence effect, framing effect, jumping to conclusions, etc.

- Outcome bias.

- When a decision is judged by its outcome, and not whether the decision process was sound.

- Confirmation bias.

- Our mind is biased to confirm a hypothesis, where good scientific work tries to prove it wrong.

- Answering an easier question.

- System 1 substitutes a difficult question with an easier one, and answers that instead. Often without you (System 2) realizing that the difficult question has not been answered.[19]

Conclusion

As described in the beginning, our society is governed by engineering systems where humans and technology are inherently intertwined. This raises the complexity and increases the number of high-risk decisions people have to make in many different professions, where project management is only one of them. If you find yourself in a position where you regularly have to make these kind of decisions, the five principles of mindfulness and knowledge about cognitive biases are tools that can help you make the right choices. In respect to the latter, familiarizing yourself with how your mind can trick you, is the only way to prevent cognitive biases from having a negative impact. Daniel Kahneman’s book: Thinking, Fast and Slow will do that for you.

Annotated Bibliography

- ↑ Johnson, N. F. (2007). Two's company, three is complexity: A simple guide to the science of all sciences, ch. 1, London, England: Oneworld Publications Ltd. - Annotation: Chapter 1 explains how complexity can be understood, and goes through some of its key components. Here, only the beginning of the chapter was used to explain that no absolute definition of complexity exists.

- ↑ Oehmen, J., Thuesen, C., Ruiz, P. P., Geraldi, J., (2015). Complexity Management for Projects, Programmes, and Portfolios: An Engineering Systems Perspective. PMI, White Paper. - Annotation: A review of the contemporary movements within the area of project, program, and portfolio management. Its definition of complexity, the section about mindfulness, and its mention of cognitive biases, was an essential first step in the shaping of the content of this article.

- ↑ (de Weck et al.,2011, p. 14)

- ↑ de Weck, O. L., Roos, D., & Magee, C. L. (2011). Engineering systems: Meeting human needs in a complex technological world, ch. 1 & 2. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. - Annotation: The first two chapters of the book is about how the human inventions begin to be connected, create networks and infrastructure, along with some of the complications on the way. It defines how we went from simple inventions, through complex systems, to engineering systems where everything is interconnected. This view was adopted here as a help to explain why the complexity of the world only is on the rise, and that new tools are required to deal with it.

- ↑ (Oehmen et al., 2015, p. 5)

- ↑ Definition of Mindfulness in English: Mindfulness. N.p., n.d. Web. 27 Sept. 2015. <http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/mindfulness>

- ↑ (Weick & Sutcliffe, 2001, p. 32)

- ↑ Weick, K. E., & Sutcliffe, K. M., (2001). Managing the unexpected: Assuring high performance in an age of complexity. San Francisco, CA: Wiley. - Annotation: Cited through (Oehmen et al., 2015)

- ↑ (Oehmen et al. (2015, p. 27-28)

- ↑ Shane, F., Vol. 19, No. 4 (Autumn, 2005), Cognitive Reflection and Decision Making, p. 27. American Economic Association, The Journal of Economic Perspectives

- ↑ Facial expression: fear

- ↑ 12.00 12.01 12.02 12.03 12.04 12.05 12.06 12.07 12.08 12.09 12.10 12.11 12.12 12.13 12.14 Kahneman, Daniel. Thinking, Fast and Slow. N.p.: Penguin, 2011. Print. - Annotation: A review of how the human mind works, with focus on the division between two ways of thinking, fast and slow. It explains the origin of many cognitive biases, and is therefore an essential piece of literature to this article.

- ↑ Chabris, Christopher F., and Daniel J. Simons. The Invisible Gorilla': And Other Ways Our Intuitions Deceive Us. New York: Crown, 2010. Print. - Annotation: Cited through (Kahneman, 2011)

- ↑ (Kahneman, 2011, p. 24)

- ↑ (Kahneman, 2011, p. 27)

- ↑ (Kahneman, 2011, p. 100)

- ↑ (Kahneman, 2011, p. 28)

- ↑ (Kahneman, 2011, p. 48).

- ↑ (Kahneman, 2011, p. 97-99)