Olympic Games London 2012: When the client strives for innovation (The London model)

Developed by Christos Stamatis

Contents |

Abstract

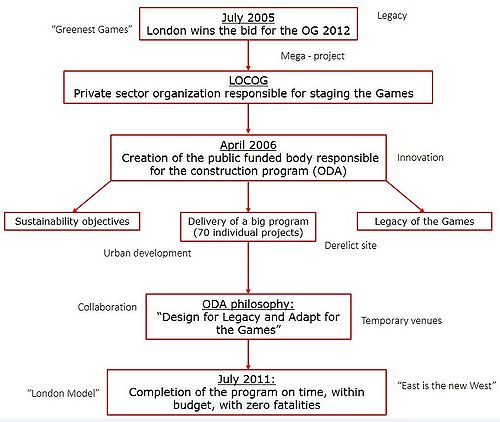

On July 2005, when London won the fight to stage the 2012 Summer Olympics, the Olympic Deliver Authority (ODA) and its Delivery Partner (CLM) were pledged to deliver the "Greenest Games" ever. They managed to deliver the construction project on time, within budget, with zero fatalities and high sustainability outcomes, striving to procure innovative products and solutions from the rest of the supply chain. The outcome of their effort, which was evaluated not only in relation to the conduction of the Games, but also to the urban regeneration of various deprived neighbourhouds and the planning of the future use of the venues, was considered succesful and provided them with great industry awards.

The rewarding aftereffect of the construction management programme was combined with the effort of documenting critical paths of the process (learning legacy), so that future mega projects or other Olympic Games could take advantage of an existing succesful 'London model' and evolve their construction process. Various aspects of the 'London model' will be analysed in this wiki article in respect to the programme management process followed by ODA.

Context

Figure 1:The Olympic Stadium [1]

Figure 2:Derelict site and proximity to city center [1]

Figure 3:Engineering works [1]

Figure 4:The Velodrome roof structure [2]

On July 2005, the city of London won a two-way fight against Paris to gain the right to stage the 2012 Summer Olympics, even if "Paris has been the favorite throughout the campaign" [3]. The crucial change in the preferences took place after an impressive presentation by Lord Coe, the bid chairman, who emphasized the cornerstone of the bid for the conduction of the Olympic Games, namely the plans to make this the most sustainable Olympic Games on record and leave a lasting legacy. [3]. The momentous day of undertaking the Olympic Games of 2012 simultaneously set a seven year countdown clock ticking for the greatest show on Earth. Following the award of the Olympic Games, the British government immediately created a new publicly funded body, which was established by an act of Parliament in April 2006 [4]. The publicly funded body was responsible to bring the whole construction project into reality and to hand it over to the London Organising Committee of the Olympic Games and Paralympic Games (LOCOG), the private sector organization responsible for staging the Games. More specifically, the Olympic Delivery Authority (ODA), as the name of this body was, had not only to plan and deliver a programme constituted out of 70 individual projects (for example the Olympic Stadium, Figure 1), translated in more than 120 principal contracts, but also to encompass the sustainability objectives and to envision the legacy of the Games. The ODA philosophy may be summarized under the quote: ‘Design for Legacy and Adapt for the Games’ [4].

The initial cost estimation by the British government was £2.4 billion for the whole construction programme. However, after revising different aspects of the programme and carefully planning the process, the ODA budget was set at £8.1 billion in 2007, including approximately £2 billion of contingency. After the initial staffing of the key positions, ODA decided directly to employ a Delivery Partner, CLM, a private sector consortium comprising a partnership from the three parent companies of CH2M Hill, Laing O’Rourke and Mace [4]. Furthermore, ODA had to confront with the major regeneration of a completely derelict and polluted site in Stratford, east London (Figure 2), which was chosen both for the proximity to the city centre of London, but also as an area of deprived neighbourhoods that was about to be developed, not only for the Games, but also for the future.

The efficient collaboration and management skills of both ODA and CLM led to delivering the venues and infrastructure programme on time, within budget and with zero fatalities, but also with several sustainability outcomes, like reduced emissions of greenhouse gases, reduced total waste, recycling during construction, as well as minimised impact of the Games on local flora and fauna [3]. During this process, ODA used procedures to ‘overcome the traditional barriers against using innovative solutions by creating the culture and conditions to embrace creativity and innovation from the supply chain’ (Figure 3).

The final cost of £6.8 billion was well within the estimation of 2007 and the programme was completed in July 2011, 13 months before the games started on 27th July 2012, providing LOCOG with sufficient time to check the venues and infrastructure for compliance with the main guidelines, as well as to prepare themselves for the conduction of the Games [5]. Additionally, as the planning and management process was considered successful even before the delivery of the venues and won various industrial awards for excellence, the need to create a documentation for replicability in future projects and programmes arose. Following that, ODA decided to create a series of Learning Legacy documents serving this scope and simultaneously contributing in government’s vision of leaving a legacy after the Games. A general overview of the construction programme is shown in Figure 5.

Challenge

Main Challenges

The complexity embodied in a system like the construction programme of the Olympic Games is already widely known. Some of the main challenges that every programme management organization will face in the case of the Olympic Games are: [6]

- Crucial importance of completing the construction in a tight, well-defined timescale with an “immoveable deadline”, corresponding to the Opening Ceremony of the Games in July 2012

The Olympic Games are scheduled to start on a specific date, which cannot be postponed. Furthermore, the requirements for venues, capacity, infrastructure, as well as other various facilities (accommodation, transportation, health and care system etc) are already defined and set the limits for the construction programme.

- Scale of the construction: 70 separate projects with significant interdependencies (common services, site logistics etc.)

The requirements related to the conduction of the Games create the necessity for a breakdown structure of the construction programme into separate projects, which are more or less interdependent. Especially in the case of the Olympic Games in London, where the site was surrounded by livable neighbourhoods, the space for logistics was constrained, leading to the conclusion that an efficient integration system of different construction processes had to be carefully planned.

- Wide range of stakeholders with legitimate influence over different parts of the programme

The management of the great amount of stakeholders is another critical part of the construction management process, as conflicting interests may arise, which have to be efficiently solved, so that the whole programme is not delayed through the Domino effect (delay of one part of the construction may lead to many other crucial delays).

Additional Challenges

Apart from the general requirements connected with such an extended, technically and politically challenging programme, the case of the Olympic Games in London created additional parameters that had to be encountered by ODA and their delivery partner CLM. These parameters are either related to the conditions under which the construction programme had to be planned and completed, as well as the objectives for the “Greenest Games” ever and the lasting legacy part that were set from the British authorities. As far as the conditions are concerned, the following points are critical and had to be deeply taken into consideration:[6]

- After the creation of the Olympic Delivery Authority, the body had five years to staff up, procure and deliver around £6 billion of major construction works

- The greater amount of construction had to take place in a largely derelict and polluted site in Stratford, which was expected to be regenerated, meaning that the planning process should target not only in the use of the site for the Games, but to the general urban development of the place for future citizens

- Fixed deadline

Moreover, ODA committed to contribute to the overall London 2012 vision of a broad legacy of economic, social and environmental benefits for London and the UK. This would be accomplished on the one hand through the implementation of sustainability strategies and on the other hand through planning for the future of the Games after their conduction in order to leave a lasting legacy that would evolve not only the UK industry, but also work as an existing successful example for future mega projects or Olympic Games under the British copyright. These commitments and requirements established the need for supplementary targets and objectives, making the programme even more complicated and complex than it was before. All these challenges were solved through innovative decisions and planning processes, which created the base for the generation of the “London model”, which corresponds to the way with which ODA and CLM treated the construction management programme from the commissioning to its delivery through a “transferable delivery-focussed governance model”[7].

Solution

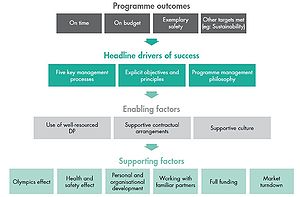

The way in which ODA dealt with the complexity of the wicked problem that they were responsible of encountering was through a framework of “drivers of success”, that is illustrated in Figure 6

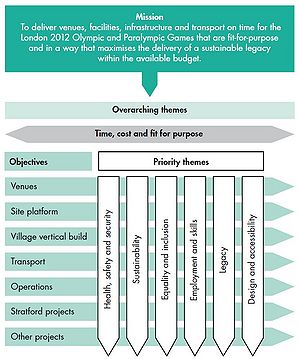

As stated before, the main objective of the Olympic Delivery Authority was to deliver the construction programme on time, on budget and with no fatalities on record. Additionally, ODA had to complete supplementary objectives, which were combined with the sustainability and legacy requirements. These targets, which constitute the secondary objectives, were described as priority themes and were embedded as a fundamental part of the overall programme governance. Figure 7 includes the primary and secondary objectives (priority themes) of ODA. The ODA followed an early briefing procedure by publishing a strategy, containing specific objectives, targets and principles which had to be fulfilled before the delivery of the construction program. These data were cascaded down to the contractors through the Delivery Partner and were non-negotiable. However, the way to implement them was left to them, strengthening ODA´s philosophy of "loose-tight" management [6].

Headline drivers of success

Following the illustration of figure 6, there were 3 headline drivers of success. Among them, the five key management processes are considered as the most innovative ones and will be analysed further. They consist of the following crucial initiatives: [6]

- Up-front planning process

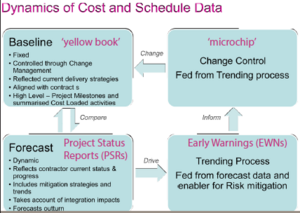

This innovative initiative was expressed through the “yellow book”, which included the definition of the detailed scope, budget, schedule, risk and interfaces of the programme (November 2007). In this way, both the ODA and CLM were stating their targets and every aspect that was closely related to them from the early construction face, so that every stakeholder was informed about the primary and secondary objectives, the ways to deal with uncertainty, risk and many other aspects. The yellow book can be considered as an innovative step for the feedback-disclosure relationship between client and stakeholders in the case of a wicked problem [8]. As David Birch, Head of Programme Controls at CLM, said, “the ‘yellow book’ produced in late 2007 was a key document for everyone on the programme. It formed the basis of our change control. It captured the scope of work that we had to deliver, the cost of that work, the timing of that work, and all the associated risks, assumptions, and exclusions. Everyone from the chief executive down referred to the ‘yellow book’. It was the key document on everyone’s desk.” [9] Furthermore, the strategic plan included in the "yellow book" contributed to the reduction of the budget. [9] This was materialized among others through the following process:

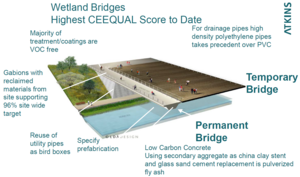

After careful planning, individual projects were selected that were specified as "not useful" for the future and were converted into temporary structures (mostly venues, bridges). Consequently, all the operational and maintenance costs for their use after the conduction of the Games were reduced. As an example, the Wetland bridges, shown in Figure 8

- Project and Programme Monitoring Process:

As described before, the whole construction programme was constituted out of many individual projects (scale of a venue). In their effort to have control over each and every individual project, ODA together with CLM followed the Work Breakdown Structure (WBS) [4]. According to this method, every complex system of the programme was analyzed into specific projects. The Tier 1 contractors of each project had to provide very detailed information on progress, budget position, future programme etc. on a monthly basis [6]. The Delivery Partner was responsible to review the monthly results together with the contractors and create an overall programme review, which was then discussed between the senior managers, involving the ODA and CLM. In general, the contractors were subject to a very rigorous audit, which sometimes led to complaints that the whole process was more a bureaucratic than a management process [6].

- Problem Resolution Process

When a problem was tracked down either from the Tier one contractors, or from CLM, the process of seeking solutions was initiated, typically between CLM and the corresponding Tier one contractor. ODA put a lot of effort on the "best solution" process, even if it required sometimes more time to be identified [6]. The appropriate example to enlighten this philosophy is the Velodrome construction. Engineers noticed that the initial incumbent steel roof design which was proposed as a solution for a self-supporting roof was too heavy. After informing the ODA through the Tier one contractor and CLM, ODA provided time for an evaluation of different possibilities, that way contributing to the innovative solution of a tensioned cable. Moreover, through the change of the contract type from target price with pain/gain to fixed price (will be explained later), ODA managed to take over the risk of overcoming the budget and replaced the possible loss of safety or security of the contractor.[6]

- Change Management Process

- Integration Management Process

In such a complex project like the Olympic Games in London, integration was more than essential in every different part of the life cycle of the program, from the planning and design until the operational handover [5]. Even if there where several aspects and parameters of integration, there were two key elements defining the management process followed, the issue identification and issue resolution [4]. Especially at the program level, important techniques were required to deal with cross-project interfaces and avoid the bow-wave effect of delay. The interdependencies of adjacent projects were monitored from CLM through the "Design Interface Schedule" system, which could define and predict the impact of one change in the design of one element (for example venue) on other parts of the programme [5]. Moreover, CLM appointed an Integration team to manage the hand-over of project domains to the various contractors [9]. The Logistics planning process was also carefully thought, even if not adequately sufficient, from CLM, as they created a Logistics team to transport people and deliver materials. This was a smart idea to avoid on-site conflicts and between contractors due to the urgent need for space. Laing O'Rourke took advantage of its experience on the Heathrow Terminal 5 project.

Enabling factors

Moreover, crucial enabling factors created the conditions for the success drivers to work efficiently. These factors are concluded in the following points:

- Use of well-resourced Delivery Partner

- Supportive contractual arrangements (The Athletes’ Village example)

- Supportive culture

Last but not least, supporting factors like the Olympics effect, namely the prestige of the Olympic games which was a driving motivating force for the whole supply chain and stakeholder group, or the full funding due to the fact that the project was mostly publicly funded, contributed in a respectful percentage on the positive outcome of the construction programme. Moreover, initiatives like the design of some venues for temporary use, so that they could then be transported in other places in the UK were considered as fully efficient in bringing into reality the vision of the future of the Games.

Implication - The real "London model"

The ODA and all the involved parties set the bar high when London won the bid to host the Olympic Games of 2012. They did not only envision successful conduction of the Games, but they also decided to incorporate elements that required more careful planning and design processes. When dealing with the Games, one thing may be concluded. The construction programme, as well as the stage of the Games were successful and simultaneously created new dimensions related to the legacy of the Olympic Games.

ODA came up with the decision of appointing a delivery partner after considering different options. Initially, they were about to select a large prime contractor for programme management and multiple contractors for project management. However, after taking the complexity of the construction programme into deeper consideration and combining it with the prime and secondary objectives they set, they decided that they needed an experienced system integrator [5]. CLM was selected as a consortium bringing together firms with a track record in successful delivery of large and complex programmes and projects [5]. CH2M Hill had a track record as a programme manager and systems integrator, Laing O’Rourke had strong capabilities in construction delivery, whereas Mace was famous for its expertise in project management [5]. ODA served as a “single governmental interface” with planning authority, without the need for various and time consuming negotiations. Nonetheless, they would not be able to work efficiently if it was not for their delivery partner, as they were a small quantity [10]. CLM worked as a consultant for the ODA with an amended NEC3 Professional Services Contract [5]. ODA was the programme manager looking “upwards” (had to deliver the project to LOCOG), whereas CLM was looking “downwards” to the Tier One contractors,simultaneously playing the role of the programme manager in relation to ODA, but also of the project manager in collaboration with Tier one contractors. Their efficient and continuous collaboration is among the most critical keys of success. Moreover, the Tier One contractors were appointed with an NEC3 C (target price/gain) or A (fixed price) contract [6], which is known for sharing the risk and opportunity between client and contractor. Furthermore, NEC is combined with many aspects of co-operative working including:[11]

- Focusing the whole team on delivery

- Equal sharing of risk

- Managing risk rather than transferring it

- Continuously assessing cost, time and quality

Besides that, intelligent procurement was a process implemented by ODA and CLM, as contractors were obliged to explain how they will implement and comply with wider policy objectives in their day-to-day activities [7]. All these relations between client and concerning parties, which were carefully chosen from ODA, following the British Standards for Programme Management [12], created the background for collaborative and efficient integration, leading to the outcome that was analysed before. Additionally, the idea of designing and constructing temporary venues and bridges created new circumstances for the future of the Olympic Games. Countries staging the next Olympic Games are able not only to create temporary structures that reduce cost and also save space, but also take advantage and reuse structures that were constructed in previous Olympic Games. Last but not least, the UK industry was able to evolve through the pressure that ODA put to them to create innovative solutions in every aspect of the design phase. This resulted in the creation of a copyright of the British expertise.

However, as it may be predicted, there were also some crucial problems that were not solved in the most efficient way. A few of these are mentioned here:

- The logistics problem: There was a big challenge of sharing space and ODA’s decision to have contractors simultaneously working on infrastructure and building projects hampered things even more. This led to programme contingency spending.[9] Jason Millet, Head of Venues and Infrastructure at CLM claimed:

“Integration, across the park, is something that we could have done better, but we made a damn good job of what we did, trying to build all that infrastructure with the venues simultaneously. More often than not, you would build the infrastructure first.” [9]

- The delivery of the athlete’s village was hit by the financial crisis and it was maybe the biggest challenge for ODA during the construction programme. Contingency money was also spent for the village [10].

- The tight relationship that ODA tried to create with the Tier one contractors through the CLM and the obligatory monthly data analysis raised their concern about the governance tactics [6].

In the conclusion, when mentioning the term “London model”, it is not about magic ingredients or other recipes. It is about the integration of a mega-project (programme) with additional requirements. It is not about innovative solutions (even if there were many of them in the engineering part), but about innovative planning process and innovative application of the existing techniques. ODA and CLM were two capable and intelligent clients that managed to take advantage of every single stakeholder responsible for each individual project after breaking down this complex mega-system.

Annotaded bibliography

Learning Leagacy, http://learninglegacy.independent.gov.uk/index.php, Olympic Delivery Authority

The Learning Legacy is a list of documents, created by the Olympic Delivery Authority that was responsible for the delivery of the Olympic Games 2012, divided into 10 themes:

- Archaeology

- Design and Engineering innovation

- Equality and inclusion

- Health and safety

- Masterplanning and town planning

- Procurement

- Project and Programme management

- Sustainability

- Systems and technology

- Transport

Each of these individual themes contains four document types, research papers, case studies, micro reports and champion products, that combine the philosophy and strategy of ODA directed to different fields. By reading some of these papers/documents, people that are interested are able on the one hand to be informed about various initiatives and innovative steps that ODA took to complete the construction programme successfully. On the other hand, they may be influenced by ideas or terms so that they search more in specific.

Graham M. Winch, Second Edition, 2010, "Managing construction projects", Wiley-Blackwell

Managing construction projects by Winch is a book that explains both in detailed and simple way different terms and processes related to construction management. Especially through pages 227-241, the reader is able to be informed about the wicked (complex) problems and how to confront with them. Apart from these pages, the whole book may be used as reference material for managerial terms (related to construction) that explain and define the various processes followed in the case of the Olympics.

Rod Sowden, Martin Wolf, Garry Ingram, Tanner James, 2011 Edition, "Managing successful programmes", Best Management Practice

Managing successful programmes is a collection of the management standards used by the British government in relation to programme management cases. It is a guide that includes key principles, governance themes and a set of interrelated processes to facilitate the delivery of programmes. Furthermore, it explains how these principles will be effectively embedded to gain measurable benefits. In relation to the Olympic Games, as ODA and consequently CLM followed this guide in many aspects of their programme management techniques, it would be helpful to try and analyse their general philosophy through this collection.

Andrew Davies, Ian Mackenzie, October 2013, "Project complexity and systems integration:Constructing the London 2012 Olympics and Paralympics Games", International Journal of Project Management

This article provides a theoretical background related to complex systems and their integration, using the Olympic Games in London 2012 as a case study reference. Through this article, the reader is able to get some stimuli to look further for the theoretical part of the complex systems. However, even in this article, through the comparison between theory and application, many conclusions can be drawn and many ODA and CLM techniques may be further analysed.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 London 2012 Infrastructure Design,Sustainability and Innovation,Inspiring an Industry and a Nation, February 2013, Professor Dorte Rich Jørgensen

- ↑ London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games The Legacy: Sustainable Procurement for Construction Projects, 2013

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Lasting Legacy, August 2012, Sean Davies

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Programme Management, Learning Legacy, April 2012, Kenna Kintrea

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 Project complexity and systems integration: Constructing the London 2012 Olympics and Paralympics Games, International Journal of Project Management — 2014, Volume 32, Issue 5, pp. 773-790, Mackenzie Ian, Davies Andrew

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 Lessons learned from the London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games construction programme, Learning Legacy, October 2011, Ian Mackenzie

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 [Governance as legacy: project management, the Olympic Games and the creation of a London model, International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development, 2013 Vol. 5, No. 2, 172–173, Mike Raco]

- ↑ [Managing Construction Projects, Graham M. Winch, Second Edition, 2010, p.227-241]

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 Delivering London 2012: Managing the Construction of Olympic Park, October 2012, Daniel Zayas

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Project management: Lessons can be learned from successful delivery, August 2012, Vanessa Kortekaas

- ↑ London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games The Legacy: Sustainable Procurement for Construction Projects, July 2013

- ↑ [Managing successful programmes, 2011, TSO Biackwell and other Accredited Agents]