Social Loafing

Contents |

Abstract

Social loafing is a psychology term that describes the phenomenon of individuals performing worse in group constellations than they are otherwise capable of, if they were working alone [1] It was first studied in the early 1900s by Max Ringelmann [2] and has since been the focal point of several empirical and theoretical studies [3] [4] [5] [6] [7]

The theories of what causes social loafing are plentiful, and includes: Social Impact Theory, Identification and evaluation potential, Diffusion of Responsibility, Dispensability of effort, The “Sucker” Effect / Aversion, Attribution, and Equity; Matching of effort and Submaximal Goal Setting [8]. Only the two first mentioned will be discussed here.

Social loafing has ramifications on group dynamic and can lead to a negative experience and in worst cases to a hostile group dynamic, in which each individual distrusts the other members of the group and refuses to put in the effort, they are otherwise capable of in a nourishing/inspirational environment. Apart from the group dynamic, social loafing also has a negative impact on the output and performance of the group work and can lead to a situation where the whole is less than the sum of all parts. This notion is from critical complexity theory, denoting how some properties found in the individual parts vanish when those parts are in a system [9].

As so much important work happens in group settings in today’s world, it is crucial for managers / other leaders to recognize the conditions that can lead to social loafing and to have strategies to prevent it from happening. Such strategies include the ability to individually measure each person’s contributions, making sure that the work is meaningful, and that each person feels like their contribution makes a difference. Furthermore, the group should feel cohesive, maximizing the incentives for each member to put in a good effort [10]. Social loafing is relevant to the management of projects, programs and portfolios, as they often involve people working in teams [11], and social loafing occurs in team settings. If there is no consideration taken of the possibility of social loafing, then the product of the work - and thus the result of the project or program, could be worse than planned and wished for. The words group and team will be used interchangeably in this article.

Brief historical overview

In 1913, Max Ringelmann conducted a study in which he wanted to determine, if there was a correlation between the effort individuals put forth and the size of the group, that individual was working with [2]. He had people pull a rope, both individually and in groups and found that the combined force used to pull the rope was less than what it should theoretically have been, given the forces that each individual was capable of asserting. This effect got the name social loafing, and similar studies were later conducted to further characterise the effect. One of these studies was conducted by Latané, Williams and Harkins (1979) [3], who points out, that Ringelmanns task of pulling a rope is maximising, unitary and additive and the task and equipment is cumbersome and in-efficient. They conducted a study in with participants were asked to clap and shout as loudly as possible. Choosing another maximising, unitary and additive task allowed the researchers to study the social loafing effect under similar conditions as in the Ringelmann study. The same experiment was done on eight separate occasions, each with 36 trials of clapping and 36 trials of shouting [3]. The study found, that while the combined noise made by the participants increased as the number of people in the group increased, it did not grow in proportion to the number of people. In fact, groups of two performed at 71% of the sum of their individual capacity, groups of four performed at 51% and groups of eight performed at only 40% [3]. These results are much in line with those of Ringelmann, further deepening the understanding of social loafing.

What causes social loafing?

Since social loafing was first studied, several theories have been applied to try and explain the effect. Some of these include: Social impact theory and Identification and evaluation potential. Other theories such as Diffusion of Responsibility and Dispensability of Effort will not be discussed here, although present in social loafing literature. As often seen with theories, they each have limitations and in reality, what contributes to social loafing on a case by case basis is likely a combination of multiple theories and phenomena.

Social impact theory

Social Impact Theory looks at the forces that play a role in an interaction between a "source" and a "target" [12]. In the situation where a manager is giving an order to an employee, the manager is the source and the employee is the target. If person A asks a favour of person B, person A is the source and person B is the target of that interaction. Social impact theory states that there are three driving forces that impact how the target (person B) will behave. Those three forces are:

- Strength - how important the source is to the target or how much authority the source has over the target.

- Immediacy - the distance in between the source and the target both in physical and temporal measures. In general, the larger the distance, the lower the impact. The more time that passes after an order has been given or a corrective action has been taken, the lower the impact will be.

- Number - the number of sources impacting the target

The relevance of social impact theory as an explanation for social loafing is seen, when the three forces are looked at from the other way around. A single source will have more of an impact if there is only one target compared to when there are multiple targets. A boss telling one employee to do something, will have a higher succes rate than if a boss asks a room full of employees for the same thing. This is called the divisional effect and stated with the terminology of the theory, the strength of the source is divided by the targets, which is also used to explain the Bystander Effect [12] . Thus, if a group of people is the target of social forces from the outside of the group, they will be less affected than an individual being the target of those same forces. In that situation, social loafing might occur.

Social impact theory have been critiqued for being situational, as it does not take into account the differences in human beings. Some people may be more or less inclined to follow the rules and respect the authority of the source in the interaction and some may be more or less inclined to take on responsibility as a product of who they are or how they were raised.

Klehe and Anderson (2007) [13] conducted a study in which they found, that none of the three personality variables conscientiousness, agreeableness and openness to experience had a significant impact on the degree to which the participants of the study were inclined to loaf. They did find, however, that people that were more conscientious were more motivated, which is normally a characteristic linked to higher involvement and participation.

Identification and evaluation potential

A fact commonly used to explain why social loafing occurs, is that generally, group members find it demotivating, when their individual performance is not measured and evaluated. It is therefore less motivating for each person to perform well, and the consequences of doing a lesser job is a lot less severe, than if the evaluation could be linked directly to that person. This notion is linked to the Evaluation Apprehension Model, that states that the expectation of being evaluated can make people behave differently. When the number of people in a group increases, it becomes more difficult to distinguish the work done by each individual and thus, anonymity increases as the group size increases [8].

In a situation where many individuals each contribute to a common goal and there is no way to identify and evaluate the work done by each person, the personal accountability for each individual is low and they are less motivated to perform well. This theory builds upon the human need to feel seen and appreciated, and has been explained in that people feel Deindividuation, causing them to loose their self-awareness in groups.

The evaluation potential not only partly explains social loafing, but also the closely related effect of Social Facilitation. Social facilitation explains the phenomenon of individuals performing better or worse in the presence of others, depending on the difficulty/complexity of the task and the level of preparation, they've done beforehand [14].

What can you do to mitigate?

Social loafing has negative consequences for individuals, social institutions and societies [3]. It results in a reduction in human efficiency which in turn causes a suboptimal result of the work done by groups. A lot of important work happens via projects all around the world at every level of society, and projects are usually done in teams [11]. Therefore social loafing must be eradicated as much as possible to obtain an efficient society. It is crucial for leaders and those responsible for group work such as Project Managers to recognise the conditions under which social loafing is likely to occur and take preventive action. However, preventive action is not sufficient if the manager has a one-sided approach and they only focus on conditions related to a single factor such as feedback, group size or goal settings. Gil (2004) [8] divides the factors that can aid in reducing social loafing into task, group and organisation related factors to allow for a systematic approach in the preventive action. An extract of Gil's recommendations is explored in the following sections.

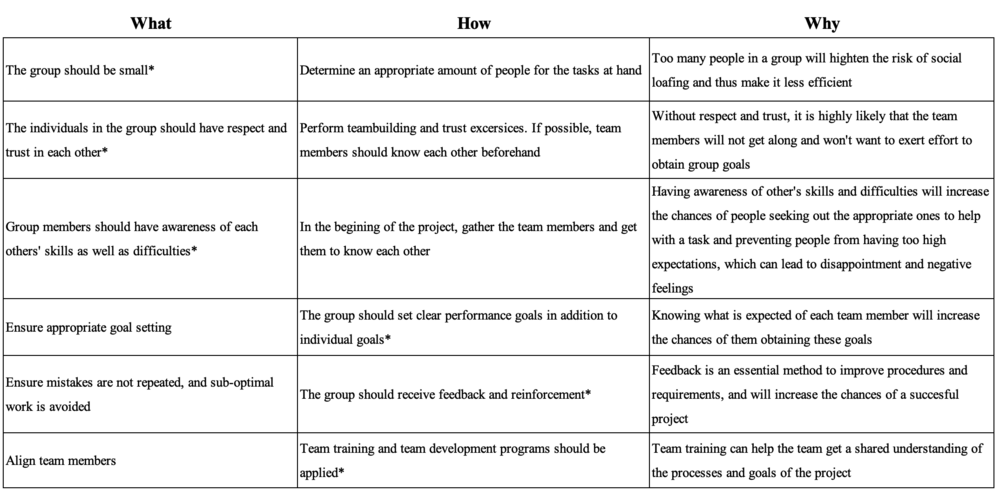

The first set of factors are those linked to the organisation. They are seen in Table 1.

What these factors have in common is that they set the project team up for succes by mainly focussing on increasing and keeping motivation for the team members. It is possible to involve the Project Manager in some of theses factors, whereas others may be imposed on her/him from the customers, the steering group, external project owners, the government etc.

A factor to highlight here, is the setting of appropriate goals. The link between optimal goal setting and motivation/performance was first researched by Locke, who came up with Locke's Goal Setting Theory of Motivation [15] . According to the theory, motivating goals have to have five characteristics: clarity, challenge, commitment, feedback and task complexity. Using SMART goals can help with the first characteristic, clarity. To make sure the goals are an appropriate amount of challenging, scenario planning can help foresee potential scenarios that can be used as a starting point for determining the range of the goal setting. When commitment or enthusiasm for the goals are diminished, members of the group will feel less motivated to assert effort into reaching the goals and thus, the performance will decrease.

The next set of factors to consider are the ones related to the group and they are seen in Table 2. This is where the Project Manager has a higher degree of influence. The overarching goal of this set of factors is to maximise the chances of succesful team work, which again will increase the chances of a succesful project.

One factor to highlight from this set of factors is the importance of having feedback processes in place and planned regularly. Not only should the project team receive feedback, they should also provide it to the Project Manager. This will allow the team members to raise concerns about any conditions that may cause them to perform suboptimal or that they are not happy with, for one reason or the other.

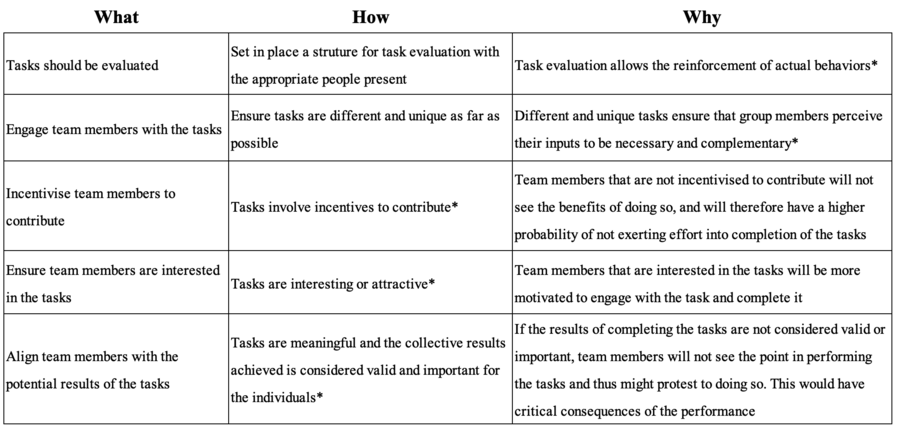

The last category of factors to keep in mind when designing the project in order to minimise the risk of social loafing, according to Gil (2004), are the ones related to the tasks. They are seen in Table 3. Here, the Project Manager will normally have a high degree of influence, as the individual tasks on a lower level tends to not be decided from a higher authority in the organisation. Therefore, there is more room for the Project Manager to design the tasks as she/he sees fitting.

The main focus of this set of factors is to ensure the team members are engaged with the tasks. Proper engagement will increase the chances of a succesful project, which in the end is the goal of trying to minimise social loafing.

A concrete tool presented by Locke [15] is to use visualisations to paint a picture of what the "to be" state would look like, if the goals are achieved. This is a way of creating incentives for the project team to reach the goal, as it will be clear for them, what they can obtain, if the tasks are completed in a satisfying way. A structured approach for setting appropriate goals is found in the book No more muddling through by Züst and Troxler [16] (p. 75).

Some of these factors might seem obvious, such as the second-to-last of the organisational factors, "Provide the necessary resources and support actions" and indeed, some of them may seem generic. However, obtaining all these factors and keeping them in mind when designing projects, might just be what causes social loafing to not be present, which will inevitably provide improved results of the project.

Limitations

While it is intuitively important to reduce social loafing and the consequences hereof, it is not easy to measure the exact effect social loafing can have in a complex setting. When this phenomena is studied, the same task is done over and over to obtain numbers and measures of the effect as exemplified by the work of Ringelmann and Latané amongst many others. In a normal, real world setting, taks and projects are not repeated simply to identify if social loafing is happening to not. Therefore, there will always be some ambiguity when relating a phenomena such as social loafing to a real world project and thus, it is not possible to state whether the risk of social loafing is present in every imaginable task. Some tasks or settings may not provoke any social loafing at all due to the nature of the tasks or the people who's doing them. As a matter of fact, several studies have looked at social loafing across different groups of people to try and characterise social loafing as either an innate human characteristic or dependent on gender, culture or surroundings and thus not omnipotent [10] [5] [4] [6] .

Gender

Karau and Williams (1993) [10] hypothesised that women in general are more orientated to maintenance of human relations and group coordination, where men are in general more orientated at achieving tasks. This would mean that women would engage less with social loafing, as they would see the group work as more important than men. In 1999, Naoki Kugihara replicated Max Ringelmanns rope pulling study put separated the participants into males and females. Both groups consisted of 18 participants, who was split into groups of 9. The participants had to pull the rope as hard as they could and the study consisted of 12 tasks for each participant, where 2 were individual tasks and 10 were group tasks. In the group tasks, the participants were told that only the collective power was gauged and not the individual contributions. The study found, that the women tended to loaf less than the men and that the mens effort suddenly declined, when the situation changed from an individual performance to a group setting [5].

The takeaway from the study for project managers is that perhaps, it is more pertinent to have awareness of the risks of social loafing if the project team only consists of men. But really, not enough research has gone into this aspect of social loafing to make gender a deciding factor for project managers. In fact, research has shown that diverse teams produce better results [17], [18]. In conclusion, while one study points to men loafing more than women, it should not be the reason for including or excluding people based off their gender. This is of course ill practice, and treating people different because of their gender in a professional setting should not be condoned.

Culture

Many important cultural differences exist across the world, and it may be that social loafing is more likely to occur in the Western societies, where individuality is central and there is an emphasis on self-sufficiency and the pursuit of individual goals. This would mean that social loafing would be less pertinent in cultures that are more collectivistic and where individual goals have a higher likelihood of being subordinate to group goals and achievements.

This hypothesis was tested by Gabrenya, Latane and Wang (1983) [4]. The study replicated the clapping study of Latané, Williams and Harkins (1979) in school children in Taiwan. Contrary to the expectation, the children showed signs of social loafing comparable to the results found in the American studies.

Another study conducted by Earley (1989) [6] researched the implications of the opposing cultural values of individualism and collectivism on an organisational level with regards to social loafing. Earley hypothesised that social loafing should not exist in a collective society. The study was conducted in U.S.A (a highly individualistic culture) and The Peoples Republic of China (a highly collectivistic culture). 48 American and 48 Chinese managerial trainees were asked to participate on a voluntary basis in a study assessing the influence of task settings on performance. The tasks included writing memos, prioritising client interviews and filling out requisition forms and performance was based on how many tasks, each person completed in a 60 minute period. Multiple conditions were set up to enact high/low shared responsibility and high/low accountability [6]. The study found that highly individualistic people performed poorest under the conditions of high shared responsibility and low accountability, whereas highly collectivistic people did not show this trend, and performed best under conditions of high shared responsibility. This however, was seen regardless of the countries from which the individuals came. Thus, collectivistic Americans did not loaf and individualistic Chinese did loaf and led the study to conclude that one's tendency to social loaf has more to do with personality traits and less to do with cultural values [6].

Precedence in Project, Program and Portfolio literature

While social loafing does not apper by name in the standards of project, program and portfolio management, the prevention methods are certainly considered in different contexts. In the PRINCE 2 standard [19] (p. 332), the quality criteria of a work package have similarities to the factors discussed in the section on Prevention and Reduction. These similarities include that standards are agreed upon before any work is done and that channels for raising issues are in place. Therefore, social loafing is in a way considered in the standards, without the standards focussing on the effect. This article seeks to deepen the literature on project, program and portfolio management, by further elaborating and shining light on the importance of planning projects with minimum risk of social loafing.

Annotated Bibliography

Gil, F. (2004), Social Loafing. This article, published in the Encyclopaedia of Applied Psychology provides a comprehensible overview of social loafing and in particular the theoretical explanations of social loafing. Most importantly, it groups the reduction factors into task, group and organizational related, which helps managers structure the prevention and reduction strategy accordingly to the level of analysis. The article furthermore provides a thorough list of additional reading materials. The author is employed at the Department of Social Psychology at the Complutense University of Madrid and has contributed with 80 publications with subjects such as leadership, team learning, virtual project teams and organisations etc.

Latané, Williams and Harkins (1979), Many hands make light the work: The causes and consequences of social loafing

This research paper provides insightful results in - and is one of the first studies of - social loafing. The paper has become a cornerstone in the literature on the topic of social loafing, with many other authors referring to it.

The paper contains a brief analysis and references to the original Max Ringelmann study, and extends the findings hereof in an interesting and easy to understand manner.

Christopher Earley, P. (1989), Social Loafing and Collectivism: A Comparison of the United States and the People's Republic of China

This research paper is a fascinating study in the nature of social loafing, and elevates the literature on social loafing to the highest levels of society. The researcher juxtaposes two vastly different cultures with the objective of mapping social loafing and linking the effect to human and cultural values in an organisational setting. The study concludes that there is a moderating role of collectivistic beliefs on social loafing but those beliefs are not necessarily limited to collectivistic societies and in contrast, that individuals in collectivistic societies may have more individualistic traits than generally assumed.

References

Citation

- ↑ Karau, S.J. (2012). Social loafing (and facilitation). Encyclopedia of Human Behavior. Second edition. pp 486

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Ringelmann, M. (1913) “Recherches sur les moteurs animés: Travail de l’homme” [Research on animate sources of power: The work of man], Annales de l’Institut National Agronomique, 2nd series, vol 12, pages 1-40

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Latané, B., Williams, K., Harkins, S. (1979). “Many hands make light the work: The causes and consequences of social loafing”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 37 (6): 822–832

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Gabrenya, Jr., Latané, B., Wang, Y. (1983). "Social loafing in cross-cultural Perspective". Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 14 (3): 368–384.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Kugihara (1999). "Gender and Social Loafing in Japan". The Journal of Social Psychology. 139 (4): 516–526

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Christopher Earley, P. (1989). "Social Loafing and Collectivism: A Comparison of the United States and the People's Republic of China". Administrative Science Quarterly. 34 (4): 565–581

- ↑ Aggarwal, P. & O'Brien, C. (2008). Social antecedents and effect on student satisfaction, Journal of Marketing Education, 30(3), 25-264

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 Gil, F (2004). “Social Loafing”, Encyclopedia of applied psychology, vol 3: 411-419

- ↑ Morin, E. (1977). “La Methode: La Nature de la Nature” [The Method: The Nature of Nature], 112-114

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Karau, S. J. & Williams, K. D. (1993). Social loafing: A meta-analytic review and theoretical integration, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65 (4), 681–706

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 DS/ISO 21500:2021. Project, programme and portfolio management – Context and concepts

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Social Impact Theory. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YRxQ-mZ6uFA. Accessed: 14.02.2020

- ↑ Klehe, U-C & Anderson, N (2007). The moderating influence of personality and culture on social loafing in typical versus maximal performance situations. International Journal of Selection and Assessment 15:2 pp. 250-262

- ↑ Social Facilitation Vs. Social loafing, PsychoGenie. https://psychologenie.com/social-facilitation-vs-social-loafing. Accessed 17.02.2022

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Locke's Goal Setting Theory of Motivation. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vtX_Ueh0j-E. Accessed on 14.02.2020

- ↑ Züst,R and Troxler, P (2006). No more muddling through, Mastering Complex Projects in Engineering and Management

- ↑ Stackowiak, R. (2018). Why Diversity Matters. Remaining Relevant in Your Tech Career. pp. 41-52

- ↑ Andrejczuk, E, Bistaffa, F, Blum et. al. (2019) Synergistic team composition: A computational approach to foster diversity in teams. Knowledge-based Systems. 182. pp. 104799

- ↑ Managing Successful Projects with PRINCE 2 (2017)