Stakeholder Analysis

Contents |

Introduction

According to the ISO 21500 standard [1] a stakeholder is defined as:

Person, group or organization that has interests in, or can affect, be affected by, or perceive itself to be affected by, any aspect of the project.

Many other versions of this definition can be found in the literature but in general containing the same content. It is important to distinguish between shareholder and stakeholder, and understand that stakeholder analysis includes analysis of the shareholders but also takes all other stakeholders into consideration.

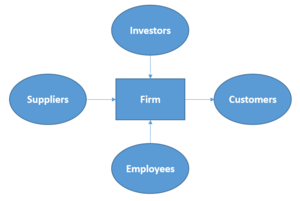

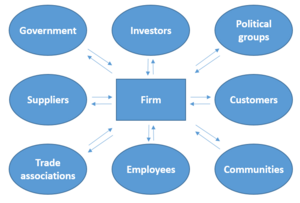

Figure 1 shows a classic input/output model with suppliers, investors and employees that provide an input so the firm can generate an output to the customers. Figure 2 shows stakeholder model where the firm are interacting with several stakeholders. The transformation from Figure 1 to Figure 2 illustrates the difference of a shareholder and stakeholder approach.

Management of a projects, programs or portfolios happens to be complex and require an extensive overview of several aspects and constraints. But in order to act appropriate and create sustainability the management often has to consider these aspects and constraints not only from their own point of view but also from a number of other stakeholders views.

It is important for the management to know who their stakeholders are and there characteristics in relation to the project, program or portfolio. This might be their influence, impact, interest, attitude etc.

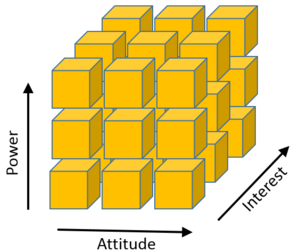

In stakeholder analysis all stakeholders first have to be identified and relevant information gathered. The stakeholders are then mapped based on relevant parameters. Some of the most typical parameters when mapping are power, interest and influence, which is often visualised in a 2D diagram. The map gives an overview of the stakeholders and can be foundation for planning how to deal with stakeholders.

Background

In 1932 Dodd started one of the first arguments that a company should not only focus on shareholders but also consider the entire spectra of stakeholders when managing a company[2]. However Dodd did not use the term stakeholder since this was not developed within this field of study yet. The term stakeholder arose in the first half of the 1960´s. Among others Freeman (1984)[3] are crediting an internal memorandum from Stanford Research Institute in 1963 for being the first to apply the term Stakeholder in this field of the literature. In 1995 Donaldson and Preston [4] described their view on stakeholder theory as the existence of three types:

- Instrumental stakeholder theory argues that companies/organisations that take stakeholders into consideration will benefit from doing so.

- Descriptive stakeholder theory is just stating that the company/organisation have stakeholders and that there they should analyse not only the shareholders but all stakeholders.

- Normative stakeholder theory evaluates why a company/organisation should take their stakeholders into consideration.

Baker and Nofsinger (2012)[5] use Coca-Cola for examplifing the three types of stakeholder theory:

- An instrumental stakeholder theorist might say: Coca-Cola should manage its water policies so as to minimize the negative impact of reputation effects on firm value.

- A descriptive stakeholder theorist might say: Coca-Cola´s water policies are an important defining characteristic of the firm.

- A normative stakeholder theorist might say: Coca-Cola has a duty to protect the environment, so it should pay more attention to its water policies.

All three theories are used in stakeholder analysis depending on need and interest. Different companies/organisation will use different approaches.

Among others Egels-Zanden and Sandberg (2010)[6] neglected instrumental and descriptive stakeholder theory.

- Dodd (1932)

- Friedman (1962)

- Stanford Institute, SRI (1963)

- Hirschman (1970)

- Friedman (1970)

- Freeman (1984)

- Milgorm and Roberts (1992)

- Donaldson and Preston (1995)

- Freeman (1998)

- Mercier (1999)

- Jensen (2002)

Process

In the literature several description of stakeholder analysis processes can be found and most large companies/organisations will have their own definition of the process. They generally follow this structure:

- A: Identify stakeholders

- B: Analyse stakeholders

- C: Engage stakeholders

Cleland (1994)[8] states a typical process:

- 1: Identify stakeholders

- 2: Gather information on stakeholders

- 3: Identify stakeholders priorities

- 4: Determine stakeholders strengths and weaknesses

- 5: Identify stakeholder support

- 6: Predict stakeholder behaviour

- 7: Prepare stakeholder management strategy

The identification of stakeholders could be done by brain storming. Typical stakeholders are:

- Employees

- Shareholders

- Media

- Suppliers

- Government

- Customers

- Community

- Managers

- Directors

- Competitors

- Sponsors

- Consumers

The list will typical also include a handful of more specific stakeholders depending on situation. The stakeholders can also be identified in a more detailed manner - fx. by different departments within the company/organisation if they fx. have different interest.

It will often make sense to identify which stakeholders are key stakeholders. The definition of a key stakeholder vary depending on type of project, programme or portfolio. Key stakeholders might by identified when mapping the stakeholders as described below.

When gathering information it is important to act neutral and not mix the collecting of information with the analysis it self.

Identifying the stakeholders priorities is the first step of the more in depth analysis. Priorities will often include cost, schedule and quality. As a tool for this phase of the analysis a stakeholder table and map are often created. A stakeholder table can typically contain:

- Stakeholder name.

- Category - fx. internal, authorities or end users.

- Relation

- Role

- Priorities

- Benefits

- Dis-benefits

- Engagement plan

The table will then act as an overview of the analysis. The mapping of stakeholders will be discussed in the section below.

Mapping stakeholders

- Why mapping stakeholders?

Types of maps

- Power/Interest diagram

- Interest/Influence diagram

- 3D mapping

- Stakeholder Circle

Challenges and uncertainty

Other methods

Methods/tools to use together with the stakeholder analysis

Further reading

Dodd Jr., E. Merrick. 1932. “For Whom Are Corporate Managers Trustees?”. Harvard Law Review 45 (7): 1145. doi:10.2307/1331697.

References

- ↑ ISO21500. 2012. Guidance on Project Management. International Organization for Standardization.

- ↑ Dodd Jr., E. Merrick. 1932. “For Whom Are Corporate Managers Trustees?”. Harvard Law Review 45 (7): 1145.

- ↑ Freeman, R,E. 1984. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach. Boston, MA: Pitman.

- ↑ Donaldson, T., and LE Preston. 1995. “The stakeholder theory of the corporation - Concepts, evidence and implications”. Academy of management review 20 (1): 65-91.

- ↑ Baker, H. Kent., and John R. Nofsinger. 2012. Socially Responsible Finance and Investing : Financial Institutions, Corporations, Investors, and Activists. Wiley.

- ↑ Egels-Zanden, Niklas, and Joakim Sandberg. 2010. “Distinctions In Descriptive and Instrumental Stakeholder Theory: a Challenge For Empirical Research”. BUSINESS ETHICS-A EUROPEAN REVIEW 19 (1): 35-49.

- ↑ Zhang, Yanru. 2011. “The Analysis of Shareholder Theory and Stakeholder Theory”. Proceedings - 2011 4th International Conference On Business Intelligence and Financial Engineering, Bife 2011, Proc. - Int. Conf. Bus. Intell. Financ. Eng., Bife: 90-92.

- ↑ Cleland, David. 1994. Project Management: Strategic Design and Implementation. McGraw-Hill Inc.

- ↑ Template:Cite book