Strategic Misrepresentation

Abstract:

Strategic misinterpretation refers to the phenomenon where an individual or an organization deliberately misinterprets or miscommunicates the actions or intentions of others in a strategic manner to further their own interests. This concept has been studied in a variety of fields, including psychology, politics, and technical aspects. Strategic misinterpretation can be used to gain an advantage in negotiations, conflict resolution, and competitive situations, as it allows individuals to manipulate the perceptions and expectations of others. However, it can also lead to distrust, and negative consequences if not handled carefully. Consequently, organizations unconsciously enhance their risk exposure and devote resources to projects that do not produce the anticipated value. Understanding the dynamics of strategic misinterpretation and how to effectively manage it is essential for successful negotiation and interpersonal interactions. In this article, we examine the phenomenon of strategic misinterpretation and its impact on communication and management. 6 Flyvbjerg B (2021) [1]

Impact of strategic misinterpretation in management

The impact of strategic misinterpretation is most significant in early project development, where measures to curb bias and misrepresentation are weakest. When presenting projects for approval during the planning and budgeting process, it is common for individuals to intentionally underestimate costs and overestimate benefits. This practice is a deliberate strategy and differs from mere miscalculations or optimism bias. Those who adopt this strategy may view it as a necessary aspect of the negotiation process and argue that disclosing the true costs at the outset would hinder the approval of many valuable projects. This often leads to cost overruns and benefit shortfalls, these are a problem as they lead to an inefficient allocation of resources, non-democratic decisions, delays and instability in project planning, policy, implementation, and operations. Thus, extremely relevant for, project, program, and portfolio managers. This communication strategy should be handled and managed carefully regarding employees and other stakeholders. Flyvbjerg B (2022) [2]

Cost overruns

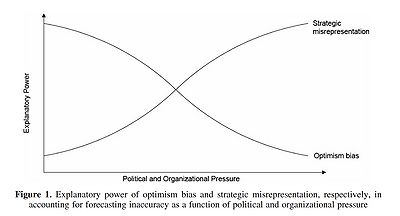

Inaccuracy in forecasts is a significant problem in management since they often lead to cost overruns. Despite claims of improved forecasting models and better data, forecasting accuracy has not improved, as highlighted by two papers in the Journal of the American Planning Association. Flyvbjerg, B., Skamris Holm, M. K. & Buhl, S. L. (2002) The inaccuracy in cost forecasts for transportation infrastructure projects was found to be on average 44.7% for rail, 33.8% for bridges and tunnels, and 20.4% for roads. Furthermore, the accuracy of rail and road traffic forecasts has not improved over a 30-year period. Various technical, psychological, and political-economic explanations for inaccuracy in forecasting have been tested, but psychological and political-economic explanations better account for inaccurate forecasts. Psychological explanations account for inaccuracy in terms of optimism bias, while political-economic explanations account for strategic misrepresentation in the decision-making process. Flyvbjerg B (2008) [3]

Strategic misinterpretation and lying

Strategic misinterpretation is closely related to lying, as both are forms of deception, but they differ in intent and execution. Strategic misinterpretation involves deliberately misrepresenting information to achieve a specific goal. In this case, the deceiver is aware that they are providing misleading information, but the intent is not necessarily to deceive or harm the other party. The deceived may also be aware that they are being deceived. Lying, on the other hand, involves deliberately providing false information, often with the intent to harm the other party. Flyvbjerg B (2021) [4]

Example of strategic misinterpretation with known data:

An example of strategic misinterpretation could occur in a political debate, where one side may strategically misinterpret a statistic by cherry-picking data, presenting misleading visual representations, using misleading terminology, or manipulating correlations to draw a conclusion that diverges significantly from the overall conclusion of the statistic. Both debating parties are likely aware that this is misleading, but the party engaging in strategic misinterpretation will often not admit to it to achieve their strategic objective.

In strategic misinterpretation the data on which the conclusion is based is not necessarily wrong, but rather, it is strategically misinterpreted. Lying, on the other hand, would involve presenting a conclusion based on incorrect data. However, in many managerial contexts, especially in early project proposals, factual data may not be conducted or available and therefore it’s difficult to lie about it. The decisions and communication would be based on assumptions based on the sometimes-limited amount of data available and here you would only be able to misinterpretation the situation and context. This could not be considered lying.

An example with unknown data:

The following passage illustrates a hypothetical scenario wherein unknown data is used to support a sales pitch. In this scenario, a salesperson presents an ambitious sales target of 100 innovative neon penguin cups for $100 each to a board of managers without any data to support the claims. The terminology used to describe the salesperson's behavior would be as follows:

Optimism bias: The salesperson genuinely believes they can sell the target quantity of 100 neon pinguin cups, but in reality, the number of cups may be way lower, say 50. This is a misinterpretation of the situation, but it is not strategic in any ways.

Strategic misinterpretation: The salesperson deliberately misinterprets the situation to align with their interests. For instance, they may believe that they can only sell 50 neon penguin cups, but they are aware that the board will only approve the project if the sales target reaches 100 units. Consequently, they strategically misinterpret the situation to make their proposal appear more appealing, but in reality, no one knows how many cups will be sold.

Lying: In this scenario, the salesperson may be aware of the board's preference for penguins, but the salesperson themselves prefers lions. Thus, they may present their proposal as neon penguin cups to appeal to the board's interests, when in reality, they are neon lion cups.

Causes of Strategic Misinterpretation

Technical explanations

Technical explanations for cost overruns and benefit shortfalls, such as imperfect forecasting, inadequate data, and lack of experience, have been commonly used. However, a large-sample study suggests that these explanations do not fit the data well. The distribution of errors in forecasts is biased, and improvements in data and methods have not led to increased accuracy. The issue is not the causes of forecasting errors, but rather the consistent underestimation of costs and overestimation of benefits. Technical explanations must account for why cost and benefits risks are consistently ignored throughout the project's development and implementation. Flyvbjerg B (2021)[5]

Psychological explanation

Psychological explanations for cost overruns and benefit shortfalls, based on the planning fallacy and optimism bias, have been developed by various researchers. The planning fallacy refers to decision-making based on delusional optimism, leading to overestimated benefits and underestimated costs. Optimism bias, a cognitive bias resulting in errors in the way the mind processes information, is thought to be a cause of the planning fallacy. While psychological explanations fit the data, they face limitations in explaining the persistence of forecasting inaccuracies over time, which suggests that optimism bias is not the only or primary cause of cost underestimation and benefit overestimation in major projects. Flyvbjerg B (2021)[6]

Political-economic

Political-economic explanations suggest that planners and promoters intentionally overestimate the benefits and underestimate the costs of projects to increase the chances of their project receiving funding. This results in the pursuit of ventures that are unlikely to deliver the promised benefits or come in on budget or time. This strategic misrepresentation can be attributed to political and organizational pressures, being in competition for scarce funds, or jockeying for position. Although this type of behavior is rational, it constitutes lying. Such misrepresentation can be moderated by measures of accountability. This explanation accounts well for the systematic underestimation of costs and overestimation of benefits found in data. However, it is difficult to determine whether estimates of costs and benefits are intentionally biased. Interviews with public officials, planners, and consultants involved in large UK transportation infrastructure projects suggest that political pressure to secure funding for projects creates an incentive structure that makes it rational for project promoters to emphasize benefits and de-emphasize costs and risks. Specialized private consultancy companies are often engaged to help develop project proposals. Consultants often justify projects rather than critically scrutinizing them, as their incentive is to make a profit. The project development process easily degenerates into a justification process, without counter-incentives, where the project concept is given an increasingly positive presentation through various stages of approval. Flyvbjerg B (2021)[7]

Strategies for Preventing Strategic Misinterpretation

To prevent strategic misinterpretation, organizations can consider implementing the following strategies:

• Clear Communication: To ensure that the strategy is fully understood by all stakeholders within the organization, it is crucial to maintain clear and consistent communication. This can be achieved by scheduling regular meetings, presentations, and memos, and by utilizing concise and easily comprehensible language. [8]

• Employee Engagement: Engaging employees in the strategy development process is essential to ensure that they have a thorough understanding of the strategy's goals and objectives. To foster engagement, organizations can organize workshops, focus groups, and other engagement activities to encourage employees to share their feedback and suggestions. [9]

• Training and Development: Organizations can offer training and development opportunities to employees to equip them with the necessary skills and knowledge to implement the strategy effectively. This may involve training on new technologies, processes, and procedures to ensure that employees are proficient and can confidently execute their tasks.[10]

• Performance Management: Aligning individual goals and objectives with the organization's strategy can be accomplished through performance management systems. This can aid in ensuring that employees are working towards the same objectives as the organization, while minimizing micromanagement and maximizing employee motivation. [11]

• Feedback Mechanisms: To ensure that the strategy is interpreted correctly and implemented efficiently, organizations can set up feedback mechanisms. This may include regular performance reviews, surveys, and other feedback channels to evaluate the strategy's effectiveness and identify areas for improvement. By employing these strategies, organizations can prevent strategic misinterpretation and achieve their goals and objectives more effectively. Recent development. Krawczyk (2023)[12]

Using reference class forecasting to estimate cost overruns

Reference class forecasting is a systematic approach used to gain an objective viewpoint on planned actions. The process involves three key steps: (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979b, p. 326).

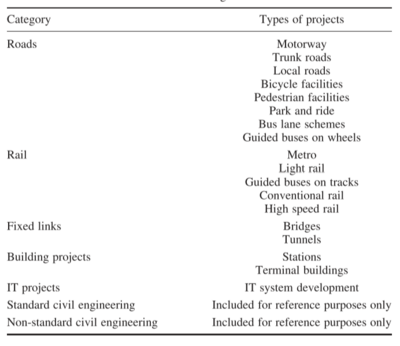

(1) Identify a relevant reference, this could bed a similar project that is broad enough to be statistically meaningful but narrow enough to be truly comparable with the specific project. However, this might not always be possible to find in a managerial context, suitable projects can be found in Table 1

(2) Establish a probability distribution for the selected reference class based on credible, empirical data for a sufficient number of projects.

(3) Comparing the specific project with the reference class distribution to determine the most probable outcome for the specific project.

Recent developments

Improvements in project development practices have emerged in recent times, after decades of mismanagement. The conventional belief that deception is a justifiable means of initiating projects is now being challenged. This shift is partly due to the fact that large-scale projects can destabilize the finances of entire regions or countries, as evidenced by the 2004 Olympics in Athens and the Hong Kong international airport (Flyvbjerg, 2008)[13] . Private investors, who put their own funds at risk, are gaining a voice in project development, and are hiring their own advisors to independently evaluate forecasts and risks. Democratic governance is also becoming stronger globally, and efforts to curb financial waste and promote good governance are increasing. Measures to limit misinformation about large infrastructure projects have been taken by governments in the UK, the Netherlands, Boston, Switzerland, and Denmark. The key weapons in the fight against deception and waste are accountability and critical questioning. The culture of misinformation in major project development has deep roots, but reform-minded groups can support and work with forces that promote change. The cost of wrong forecasts and decisions should fall on those making them, and institutional checks and balances should be employed. While this culture change is difficult to achieve, it is important for saving taxpayers from waste and protecting democracy, the rule of law, and environmental assets. (Flyvbjerg, 2008) [14]

Other types of behavioral biases in project management:

1 Optimism bias is the tendency to be overly optimistic about planned actions, leading to overestimation of positive events and underestimation of negative ones.

2 Planning fallacy is the tendency to underestimate the time, resources, and costs required to complete a project, while overestimating the expected outcomes. This bias can lead to missed deadlines, cost overruns, and subpar results.

3 Uniqueness bias The tendency to perceive a project as being more unique than it actually is.

4 Overconfidence bias refers to the tendency for individuals to have too much confidence in their own answers or abilities when answering questions. This bias can lead to poor decision-making, as individuals may overlook important information or fail to consider alternative viewpoints.

5 Hindsight bias, is the tendency to see past mistakes and events as more predictable than they actually were. This bias can lead to a false sense of security and a failure to learn from past experiences.

6 Availability bias is the tendency to overestimate the likelihood of events that are more easily retrievable or available in memory. This bias can lead to a failure to consider less salient but more relevant information, resulting in poor decision-making.

7 Base-rate fallacy refers to the tendency to focus on specific information related to a particular case or small sample, while ignoring more general base-rate information. This bias can lead to faulty conclusions and poor decision-making.

8 Anchoring is the tendency to rely too heavily on the first piece of information acquired when making decisions, often leading to errors in judgment. This bias can lead to overconfidence and a failure to consider alternative viewpoints.

9 Escalation also known as the sunk-cost fallacy, is the tendency to justify increased investment in a decision based on the cumulative prior investment, even in the face of new evidence suggesting the decision may be wrong. This bias can lead to a failure to cut losses and a persistence in pursuing a failing course of action.

10 Illusion of control is a false belief that individuals have more control over outcomes, decisions, and actions of external actors than they actually do. This bias can lead to overconfidence, a failure to consider alternative viewpoints, and poor decision-making.

It’s worth mentioning that other types of behavioral biases exist such as conservatism bias, normalcy bias, recency bias, probability neglect, the ostrich effect, and more. These 10 biases may be considered the most influential regarding management. Flyvbjerg B (2021) [15]

Refrences:

Muta, S. A. (2014). "The Art of Deception in International Relations."

Flyvbjerg, B., Skamris Holm, M. K. & Buhl, S. L. (2002) Underestimating costs in public works projects: Error or lie?, Journal of the American Planning Association, 68(3), Summer, pp. 279–295.

A. (2013, December 21). "Strategic Misrepresentation – Why Do Projects Fail?" [16]

Donnenwerth, C. B. (2007). "Communication and Deception." American Planning Association. (1991). "AICP Code of Ethics and Professional Conduct." Adopted October 1978, amended October 1991. [17]

Flyvbjerg, B. (1996). "The Dark Side of Planning: Rationality and Realrationalität." Flyvbjerg, B. (2005). "Design by Deception: The Politics of Megaproject Approval."

Harvard Design Magazine, 22(Spring/Summer), 50-59.

Flyvbjerg, B. (2008). "Curbing Optimism Bias and Strategic Misrepresentation in Planning: Reference Class Forecasting in Practice." [18]

Flyvbjerg, B. (2021). "Top-Ten Behavioral Biases in Project Management: An Overview." [19]

Flyvbjerg, B. (2022, February 12). "Strategic Misrepresentation: The Blind Spot in Behavioral Economics." Medium. [20]

Greg Krawczyk. LinkedIn, 7. March, 2023. " How to mitigate strategic misrepresentation and unlock data, a project management focus. " by [21]