TFV-model

Developed by Somar Faraj Hassan

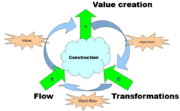

The TFV-Model is an important model in the Lean construction Theory. TFV stands for Transformation (operations), Flow (processes), and Value. The model represents the relationship between these three main components of the management of a construction project, and how they all contribute to its success. The emphasize is placed on creating value for the customer, eradicating non-value adding (waste) activities, and mainly controlling the processes (flow) in a project rather than the operations (transformations/activities) them self. It’s therefore suggested that a process manager should be assigned to any given construction project, and whom would have a vital role for its success.

Contents |

Lean Construction and the TFV theory

Lean Construction is inspired by the general lean production theory, and many of its key concepts are directly taken there from. The biggest difference between the two is, that the construction business works in temporary projects rather than in a continuous production. However Lean Construction tries to benefit from the lean production concepts and methods as much as possible and largely tries to look at construction projects as a form of production.

The TFV theory is the main concept in Lean Construction which connects the construction project to production ideas. A discussion of the wording behind “TFV” have occurred about whether or not it’s as appropriate for construction projects as it’s for the production industry. Lean Construction Denmark, the main contributor to the concept in Denmark, have argued that Operations are a more appropriate word than Transformation for the model, since it covers a larger group of activities including non-value adding ones, such as transport, awaiting, and inspections. The reasoning is that such activities should also be included in the wording since they are often paid for equally to the transformative (value-adding) activities. It’s also argued that the prioritized order for the three words should be Value, Flow, and Operations, hence the model should actually be called the VFO-model. However, they have not changed the known name of the model because of the international recognition of it. [1]

Value creation

Value creation, -the starting point of the TFV-model and the main objective of the concept, is reached through the flow and transformations. In order to create value for the customer it’s therefore important to understand his/hers needs which decides the baseline for what quality is and the prioritization of the project deliverables. Value Management is by itself a discipline where customer value is seen as a changing factor which the contractor is also able to influence. Operations and processes is always measured on to what degree they are creating value for the customer and whether or not they are doing it at all. It’s thereby not worth it to spend resources on non-value adding activities and processes unless they are absolutely necessary; which in that case they should at least be minimized as much as possible. [1]

In the lean theory non-value adding (wasteful) activities are placed in seven categories, which are:

- Overproduction

- Waiting

- Transport

- Over-Processing

- Inventory

- Motion

- Defects

All of these categories can be related to the construction industry and The Seven Wastes lean concept is therefore inevitable a practical tool in the lean construction process.

Flow

Flow and operations can be seen as two different dimensions of the production. The flow is what happens to the product throughout the production while the operations are what is executed by workers and machines. Optimization of the production should therefore be focused on the flow rather than the single operations; this is because the flow as a whole is what creates value for the customer rather than the single operations. The message basically is: Do the right things before you do things right. [1]

A central concept in regard to optimization of the production flow is the movement from push- to pull logistics. This concept can to some degree be extended to the construction industry. It basically means that a material or product should not be delivered unless it’s requested by the following operation in contrast to it being delivered whenever it’s ready, even though it might not be needed at that time or not needed in such quantities at all. One of this concepts most important benefits have been to eradicate pending inventories and instead getting materials delivered or processed only when needed and when the following process is ready to receive it. Another beneficial concept that have emerged after the pull concept is the ready-for-use packaging idea. Instead of having many separate orders delivered to the same operation, all deliverables needed for that single operation should as far as possible be delivered in one package ready to be implemented. Here it’s important that nothing else, related or unrelated, should be delivered to that operation if it’s not needed at that point of time in the flow. A good example is the Ikea furniture package, -it has all necessary parts to build the finished product and nothing else, neither is anything missing in it. However, if for example a set of doors needs to be delivered to a construction site, handles should be included in the package while delivery of locks might be delayed until the end of the project where they usually are installed. In this way the locks won’t be lying around for a long period of time where some of them or parts of them might become missing. Another thing is while e.g. 50 doors might be needed for the whole construction project, only the needed amount at a given time should be delivered, so a space requiring inventory won’t pile up.

Such concepts, and others as well, all contribute to the optimization of the flow and a better execution of the project. [1]

Operations (transformation)

From the operations perspective, activities can be divided into value- and non-value adding operations. Whereas value adding activities all together, is the processes that at each operation transforms the subject to a more valuable product until it ‘reaches’ its final form and is delivered to the customer. From a holistic TFV-perspective the value of each transformation should be increased, and the non-value adding operations should be eradicated or at least minimized as much as possible.

Examples of non-value adding activities could be transportation, awaiting, and inspections. Time and money used on such activities should be minimized, which can be done through other Lean methods and concepts. As explained earlier, optimization of single operations does not have the highest priority from a Lean perspective, instead it is given to optimization of the flow. However, the two are closely related, and an optimization of operations are often needed in order to optimize the flow. A production example is the optimization of the changeover times in a production line in order to create a better and more flexible flow of different products produced at the same machines and work stations. This will inevitably also require an optimization of the single operation which might not be a technical easy task. [1]

Implications of the TFV-model

An important implication of the TFV-model is that while value should be created through the flow and operations, optimization can also be achieved in between them, -that is the work-flow. A better work flow, among other things, means that the different operations are performed in pace with each other. It’s not sufficient that a certain operation works much faster than the following one, since the following operation will become a bottleneck for the flow. A work-flow where the sequential operations are in pace with each other is therefore needed. One way to optimize the planning of the project flow is through Location Based Scheduling. (Please see the link for more information on this method) In short it is to move from a classical Gant schedule, which simply arrange activities in their sequential order with only some flexibility which allows overlapping activities, to a schedule based on the work locations where activities are represented as one or more lines across the calendar. This allows much more flexibility in the planning and makes holes in the schedule obvious for locations that are not yet finished. [1] Please see the example on the right hand. [2]

Value Management

Value Management is shortly about managing and directing the project towards the value that is needed by the customer. It’s therefore also to understand and monitor the needs of the customer, and also to influence them. It’s important to understand that what the customer values might not be that clear, not even for him/her self, and that it will change over the duration of the project. The contractor is also not limited to only understand, observe and monitor those needs, but he/she is also able to influence them – and is always doing it, either intendedly or unintendedly. This understanding can be beneficial for both the customer and contractor, and doesn’t have to be used in an evil-intended manipulated way. Rather it can become the key to matching the expectations between the two parties and satisfy the customers’ needs much better. [1]

Value Management methods is also proposed in Lean Construction, and the value focused construction project have been divided in to two main stages; the value formulation and the value delivery.

The value formulation is about creating as much value as possible within the budget of the customer. In this process value is seen as a biased and dynamic entity, and the owner is seen as a complex ‘system’. The owner is therefore not expected to be objective, rational, or exhaustive in his/her value formulation and expressions. As mentioned earlier, he/she is neither seen as static, rather his/her perception of value is seen as changing over time and different learning phases. It’s therefore said that the owner is an emerging and complex phenomena. This stage takes place from the definition of the architectural procurement until the actual start of construction.

In the second stage, the value delivery, the value formulation is finished, and it’s now up to the contractor to deliver that value as effective as possible. Which takes us back to some of Lean Construction core principles about maximizing value and eradicating waste/non-value adding activities. The process which takes place at this stage is also called Value Engineering. [1]

The Process Manager

The key difference between the process manager and the traditional project manager is that the process manager won’t dig into the details of the different operations, rather he/she will focus on the flow of the project, and leave the responsibility of the execution of the operations to the employees and subcontractors themselves. This does not mean that the quality control should be compromised, rather it’s a different approach of controlling the operations, emphasizing on trust and target management. It’s thereby also a way of empowering employees and subcontractors, sharing the sense of responsibility more equally. The process manager needs to have the overview of the project and control the flow so it can run as smooth as possible. [1] A number of tools have been developed for that purpose. Some of the before mentioned tools specifically can be used to manage the flow, such as Location Based Scheduling and The Seven Wastes. Another central process managing tool in Lean Construction is the Last Planner System. Before we dig into the LPS, it’s important to note that the role of the process manager is largely seen as complementary to the traditional management positions, and have been implemented in numerous ways depending on the needs of the project management team; an example is given in the next section.

The Last Planner System, is a method that takes a different approach to plans, they should not be seen as orders, rather they should be seen as mutual agreements between equal parties. The reason is that an agreement binds both parties to be equally committed, whereas such commitment is normally not found in an order. This requires many targeted plans with only a few interconnected objectives at one plan to be formulated, in contrast to the normal universal time plan, which has multiple different objectives. In addition, the plan is not seen as truly reachable, with the reasoning that plans normally can’t be fully followed because of uncontrollable events, which will always occur, even when looking at a short term of time. A very detailed master schedule given by the owner is therefore seen as having only little value because of the low chance of being able to follow it into every detail and the unknown factors of time.

The Last Planner System is now divided into multiple types of plans, each one with its own purpose. These plans are: Phase schedule, list of obstacles, Look Ahead Plan, Weekly Work Plan, Percent Planned Completed (PPC). [1] For details on each type of plan please refer to this site: The Last Planner System in Construction Projects.

Examples of usage

In 2003 at the International Group for Lean Construction 11th. annual conference a paper called: ‘The experience and results from implementing Lean Construction in a large Danish contracting firm’, was published. The paper explores the experience of the Danish contracting firm, MT Højgaard, after one year (2001-2002) of actively implementing Lean Construction methods in 19 building projects in there housing division. The 19 project experiences summarized in the paper vary great in nature and size, and the joint experiences are therefore considered to be of a very general character.

The chosen Lean Construction tools to be implemented at the time in MT Højgaard were the following: Dynamic Planning, weekly evaluations, plan coordinating, Material Logistics, PlanLog (special designed software), and The Process Manager.

It’s the last ‘method’, the use of Process Manager, which is of great interest for this wiki article. As mentioned before the usage of a Process Manager in any building project is a good method to ensure the implementation of the TFV concept. In MT Højgaard the process manager was introduced as a process ‘coach’ without any formal responsibilities concerning legal or economic issues. Rather his/her role was to facilitate the bottom up planning on site by ensuring a good collaboration between the project management and the subcontractors, as well as between the subcontractors them self by assisting the team work in between them. While the other Lean Construction methods and tools were not all introduced and implemented into all of the 19 building projects, the process manager was used at all building sites because of essential role for a lean construction management.

MT Højgaard compares the results of the projects exploring Lean Construction tools with other similar traditional managed projects through benchmarking. Because of MT Højgaards lack of focus on the client using the different tools, only a small increase in customer satisfaction was registered. Though it is interesting to notice that the overall set of projects only has one perfect score for customer satisfaction, and that this project was a successfully conducted Lean Construction project.

The data, though inadequate, suggests that Lean Construction projects in average performs better in regard to net profits.

To measure the difference in profits of subcontractors, MT Højgaard compared the profits of their internal carpentry division in regard to LC and non-LC projects. Lean Construction projects turned out to generate an approximately 10% better profit in average.

Interestingly in general rates of illness and accidents for workers were greatly improved for the Lean Construction projects.

At last only a very small difference in project management cost were detected, which overall implies that the benefits of implementing Lean Construction have been much greater than the costs. [3]

Criticism

Lean Construction and some important aspects of the TFV-model have been criticized by critics concerned with human resource management (HRM) issues. It’s said that the methodology uses a highly instrumental view of workers, pushing the limits of effectiveness with concepts as The Seven Wastes, promoting more value-adding activities at less time and annihilation of non-value adding activities. Besides the health and perseverance concerns the criticism indicates, it has also been pointed out that this kind of exploitation of workers might deter young and creative minds from the business. That is in a time were fewer young men and women shows interest in the construction business as craftsmen. [4]

Annotated Bibliography

Foreningen Lean Construction–DK (2012). Håndbog i Trimmet Byggeri, version 2.1.

This Lean Construction book, or rather handbook, by the main Danish Lean Construction organization for businesses, is basically an overall guide and introduction of everything you need to know about Lean Construction to get started. It provides a good introduction to LC and its Danish context, and builds up the conceptual fundament for LC methods and tools. It’s the main source for this article because of its exhaustive treatment of the subject, and is highly recommended for newcomers.

Andersson, N., & Christensen, K. (2007). Practical Implications of Location-Based Scheduling. In CME25: Construction Management and Economics: past, present and future. Taylor and Francis Group.

This article looks into the practical implications of Location Based Scheduling and gives a short overview of the method. It’s practical oriented and it’s based on three practical site management cases, where it searches to explorer the benefits and limits of the tool. In this wiki article it has mostly been used as an example of improving site planning through LBS-sheduling.

Thomassen, M.A., Sander, D., Barnes, K.A., Nielsen, A. (2003). The experience and results from implementing Lean Construction in a large Danish contracting firm. Presented at the IGLC-11 conference 2003.

This article outlines the, at the time, given results from the implementation of Lean Construction methods and tools in 19 different construction projects in MT Højgaards building division. That is around 40% of the division with about 1 year of experience. MT Højgaard implemented various methods and tools in the different projects, but did not use all of the tools or the same tools in all of the projects. However, the process manager was used in all cases. The conclusion of the report is clear, in some areas of comparison Lean Construction methods were beneficial and further analysis is encouraged. In this wiki article the example has been used in the ‘Examples of usage’ section, please refer to it for more details.

Green, S.D., (2002). The Human Resource Management Implications of Lean Construction: Critical Perspectives and Conceptual Chasms. Department of Construction Management & Engineering, The University of Reading.

This article is a critical review of Lean Construction methods from a Human Resource Management perspective. It criticises the instrumental view of workers in Lean Construction and how it negatively affects them and the influx to the industry as well. The criticism is primarily pointed at the lack of consideration for the craftsmen work environment during the discussions on value-adding effectiveness. For more information see the ‘Criticism’ section.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 " Foreningen Lean Construction–DK (2012). Håndbog i Trimmet Byggeri, version 2.1."

- ↑ " Andersson, N., & Christensen, K. (2007). Practical Implications of Location-Based Scheduling. In CME25: Construction Management and Economics: past, present and future. Taylor and Francis Group."

- ↑ " Thomassen, M.A., Sander, D., Barnes, K.A., Nielsen, A. (2003). The experience and results from implementing Lean Construction in a large Danish contracting firm. Presented at the IGLC-11 conference 2003."

- ↑ " Green, S.D., (2002). The Human Resource Management Implications of Lean Construction: Critical Perspectives and Conceptual Chasms. Department of Construction Management & Engineering, The University of Reading."