The Agile Stage-Gate Model

Contents |

Abstract

The Agile-Stage-Gate model is a hybrid project management approach used in the development of physical products[1]. As the name may suggest, the model aims to merge two different, almost opposite models, the Agile frameworks and the Stage-Gate® (Stage-Gate® is a registered trademark of Stage-Gate Inc, www.stage-gate.com) to create a new flexible but structured solution[1]. Currently, gating systems are considered “too linear, too rigid, and too planned” (Edwards et al. 2020)[1]: generally, unable to keep up with the high degree of uncertainty that characterises modern projects. Agile methodologies (Scrum above all, but also other practices such as Design Thinking and Lean Startup) [2] can be embedded inside stages to deal with the contingencies of the project[1]. In practice, the Stage-Gate® continues to give the project a step-by-step path from ideation to the launch in the market, while Agile is applied as a tool in daily activities. According to the latest studies, the results from on-the-field experiences state that the Agile-Stage-Gate can improve the product development process in several ways, such as by making the design processes more flexible, achieving higher productivity, supporting better communication and collaboration in teams, and higher team morale [1]. Some studies also highlighted a higher success rate and a faster development process [1]. The model is applied by large companies such as Lego, Volvo [1] and Danfoss [3], and it has also yielded encouraging results in small-medium enterprises [1]. However, it poses new challenges to managers in allocating resources, building complete multidisciplinary teams [1], organizing meetings [1], and overcoming the skepticism of the management. Differently from previous articles on the same subject [4], this article not only aims to investigate the new hybrid approach's origins, nature, and functioning from its foundations, but it also will provide recommendations on when to use a specific hybrid model based on the latest scientific contributions. Furthermore, the article will report the most suitable metrics to evaluate Agile-Stage-Gate projects from a portfolio perspective. In conclusion, a brief reflection on the status quo of the developmental approaches against what the Agile-Stage Gate proposes, followed by the limitations of the model.

Why the Hybrid Model

Managing Innovation through the Stage-Gate®

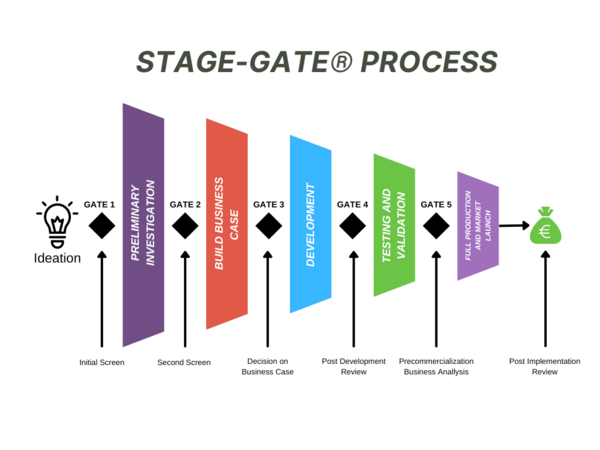

In the second half of the 20th century, gating systems for project management spread all over the world and became a standard in riding the lifecycle of innovation projects, especially in new product development. One of the most famous gating systems is the Stage-Gate® model, formulated by Cooper in 1983 [1], a strategic management tool that gives a rigid and plan-based structure to the "idea-to-launch"[5](Edgett, 2015) process, alternating decision-making stations called Gate to operative Stage. A Gate is a set of expected results that must be met by the project leader to access the next Stage. The “exit criteria” vary from one gate to another, or from one project to another, but generally, they should be a set of benchmarks for the project's strategic, marketing, and financial aspects [5]. Initially, these standards are mostly qualitative, while they gradually become more quantitative in the final stages[6]. The evaluation of the current state of the project against gate criteria needs to be assessed by an experienced manager, whose knowledge plays a key role in the decision-making process. Management oversees the greenlighting of the heavy spending decision through the path and helps the team meet the deadlines. Furthermore, management's commitment and support are fundamental in aligning the project's development with the organization's objectives [5]. The evaluation of the deliverables in a Gate results in a Go/Kill/Hold/Recycle decision [5]. If the deliverables satisfy the exit criteria, the project can move on to the next Stage, “a set of required or recommended best-practice activities needed to progress the project to the next gate or decision point” (Cooper, 2008) [7]. In each stage, cross-functional types of analysis are carried out concurrently by multidisciplinary teams of individuals from different areas of the company[6], using traditional project management tools such as “Gantt chart, milestones, and critical path” [3](Cooper, Sommer, 2018). Since every stage has incremental costs, the knowledge acquired thus mitigates the risk. Each stage offers a broader vision and a more analytical perspective to decision-makers, who can evaluate the project using objective data rather than relying on intuitions [6]. An example of a traditional Stage-Gate® model introduced by Cooper in his article "Stage-gate systems: A new tool for managing new products"(1990) is reported below [6]:

- Preliminary assessment: Users’ feedback about the concept is gathered through quick research to evaluate how the product would be perceived by the customers [6].

- Definition: Customers’ preferences are deeply analyzed in this stage. Thus, the team can identify the basic principles of the future product and draft the first approximate financial and technical prospectuses. Here, legal matters are also considered[6].

- Development: the design of the product is finally developed, and all operative needs and processes are clearly defined [6].

- Validation: once the product is prototyped and ready to be produced, the company must test it to evaluate its quality. The customer plays a crucial role in helping the development team to understand if the usability of the product is by what has been stated in the previous stages. After the first tests, more information is available and can be used to improve the product and the production process. Furthermore, considering the new data, the financial prospect of the entire project can be reassessed [6].

- Launch: The product is finally launched on the market, and production can start [6].

The Agile-Stage Gate: need for flexibility

At the management level, the two questions “Are we doing the right things?” and “Are we doing things right?” are more and more present and require the review of existing strategic and operative plans [3]. In Stage-Gate®, a detailed product proposal is well-defined before starting a project, and project-related costs are evaluated and approved upfront. [3]. Moreover, in the traditional method, the team follows a sequential path based on a predetermined schedule and project blueprint, and the customer is rarely involved in the process[9]. This approach clashes with the dynamics of the current environment, which asks companies to be flexible and adapt to the market’s changes[9]. The traditional model has been criticised in several respects. Having project details fixed too early may require rework or compromises in later stages, with negative effects on the time-to-market and the quality of the output. Moreover, excessive bureaucracy makes the model too rigid. In general, gating systems are "not adaptive enough and do not encourage experimentation"(Edwards et al. 2019)[1]. For this reason, the hybrid Agile-Stage Gate approach gained interest among scholars and practitioners as a possible alternative that blends benefits from both models, thus balancing “discipline and agility” [10] (Brandl et al. 2018). Agile project management is a project management approach that handles complexity by iterative work on the product, adapting its features to the emergent business needs in the process [11]. Even if most of the agile frameworks had been developed during the second half of the 20th century, the Agile philosophy was officially formulated by a group of developers only in 2001, with the publication of the Agile Manifesto [12]. As affirmed by Abbas et al. (2008) a method, to be considered agile, should be “Adaptive”, “Iterative and Incremental”, and “People Oriented”[13].

- Adaptive: ready to adjust the product, or the “method itself”(Abbas et al. 2008)[13], to what is needed after each iteration, based on technological advancements and feedback from previous iterations.[13]

- Iterative and Incremental: in a software environment, the features of the product are defined iteratively, and incrementally improved. At the end of each iteration, the customer is involved in the evaluation to gather his opinions and ideas during the process.[13]

- People Oriented: the Agile philosophy considers the method applied as a mere tool to support the team in delivering the best possible outcome. The role of people, both the team and the customer, is pivotal in agile philosophy. [13]

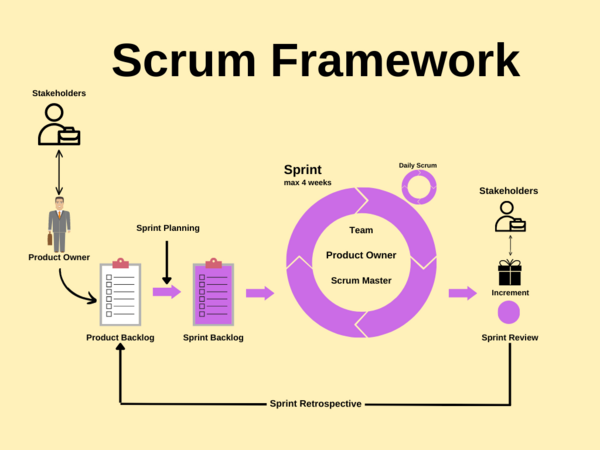

Generally, the Agile mindset is an “umbrella” that groups a wide number of frameworks, such as Kanban, Extreme Programming, Scrum, and others [14]. In the context of the Stage-Gate®, the Scrum framework seems to be the aptest to be fitted into the stages [15]. In a nutshell, Scrum is an agile project management methodology inspired by rugby that through time-boxed iterations(“Sprint”, usually lasts from 2 to 4 weeks) aims to create a certain improvement, called “Increment”, into the product in the development pipeline. At the end of each sprint, the outcomes are evaluated with relevant stakeholders in a review session (“Sprint review”). Stakeholder feedback helps the team to update the Product Backlog with new functionalities to be added in the next sprints. Then, the whole sprint is reviewed in a retrospective meeting (“Sprint Retrospective”), where the team discusses what worked well, and what did not, and identifies the key area of improvement for future iterations. [16][17]

The Scrum team consists of three main figures:

- The Scrum Master, the team leader who helps members apply Scrum methods and practices in daily activities. The Scrum Master works on the interface between the team and the organization.[16]

- Product Owner, who translates the stakeholder needs into achievable objectives, grouped in the Product Backlog. Moreover, The Product Owner is accountable for listing, prioritizing, and communicating the items in the Product Backlog to the team.[16]

- Developers, the professionals who actually “create” the Increment. The Developers plan the Sprint together and work to meet the quality criteria defined in the Definition of Done, thus realizing an Increment.[16]

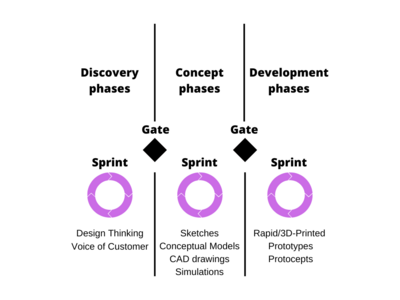

However, other Agile methodologies can be used to improve the existing product development roadmap, such as Lean Startup and Design Thinking [2]. According to Cooper and Sommer [15], in the first decade of 2000, some IT companies showed that the combination of the two models was possible. Firms in this field often aimed to develop a product that involved both software and hardware parts. The development of each of these two components was strongly connected to the other, and the processes were also linked to several different functions that had to be aligned to reach a common goal. These companies already applied their phase-gate and agile models to the development of new products. In this context, the traditional gating system fostered the communication inter-teams involved in the project and gave support to the project's sponsors. On the other hand, agile practices were applied to control and plan the daily project tasks, and keep track of the project advancements. The mix provided benefits and created new challenges, but generally, it proved that the coexistence of the two approaches was possible [15]. Nowadays, the hybrid model is relevant even for those companies that develop physical products. New technologies on the market allow teams to develop and test new ideas faster, reproducing working rhythms common in software development. In this context, the importance of agile arises even in the manufacturing world, and a new way of exploring new solutions is needed. (Cooper 2016) [18]. In practice, the Agile-Stage Gate model revolutionizes traditional project management in new product development. Gantt Charts, milestones, and critical path planning are replaced with agile practices and tools. [19] Inside each stage, the development process is divided into sprints, at the end of which the product should have gained an incremental improvement. [19] Differently from the traditional Stage-Gate®, a short-term planning approach drives the projects. [19] The merge of these two models gives the product development process a structured plan from a strategic side (Stage-Gate®) while providing enough degrees of freedom to adjust products and action plans along the way at the tactical and operational levels. [10] The product is developed through sequential iterations: at the end of each one, the team should aim to design a prototype ready to be presented to the client to gather useful feedback and plan the goal for the next iterations [19]. There is no common terminology to define the Agile-Stage Gate. Often, the “Agile-Stage Gate” label is used to refer to the Scrum-Stage Gate hybrid.

According to Cooper and Sommers [3], the results for early adopters are encouraging. Chamberlain, a company operating in the field of home devices, applied the Agile-Stage-Gate to better coordinate the development of hardware and software components. They broke down each stage into different three-week sprints. The company achieved impressive results in terms of productivity and reduction of cycle time. Danfoss implemented sprints in the design and validation phases, with a 30% reduction of time-to-market. GE implemented a hybrid model in the development of aero-engines. The company used Lean Startup practices in two of its three-stage gating system (respectively Seed and Launch of Seed-Launch-Grow). They managed to halve the time required to test an engine. Honeywell, after the implementation of a tailored hybrid model, experienced positive effects on the internal culture and carried out successful pilot projects.[3]

Hybrid Models in practice

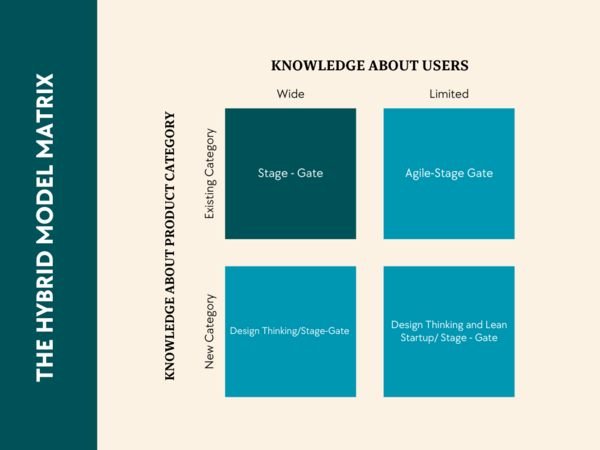

Traditional or Hybrid Model? The Hybrid Model Matrix

Cooper and Sommer, in their article “From Experience: The Agile-Stage-Gate Hybrid Model: A Promising New Approach and a New Research Opportunity” (2016), asked the question of “when to use Agile-Stage-Gate?” [15]. They suggested that the Agile Stage-Gate could be applied for radical and incremental product development[15]. Generally, the Agile-Stage-Gate seemed to work better in contexts with “high uncertainty and a great need for experimentation and failing fast”(Cooper, Sommer, 2016)[15]. However, answering the initial question may still be difficult. A study by Cocchi et al. (2021) [2] introduced a tool for project managers, the Hybrid Model Matrix, that aimed to make easier the decision-making process to choose the right model for the right project. The matrix has been defined as a result of a case study carried out on a firm in the food industry. This company applied hybrid models combining a six-phase Stage-Gate (Ideation, Concept, Business case, Development, Testing, and Launch) with different Agile methodologies, such as Scrum, Lean Start-up, and Design Thinking practices.[2]

Although the company applied the most recent techniques, it lacked a structured framework that could facilitate the decision on the appropriate methodology to be employed for a given project. The choice of the model depended on the management’s on-the-field knowledge and their ability to evaluate resources in conjunction with the project's financial return. [2]. The matrix states two important factors to be considered before the start of the process:

- Knowledge about Users (KAU): this could be “wide” or “limited” and it refers to the point of view of the customers. “Wide” means that the company is aware of costumer’s tastes and preferences. The target is clear. On the contrary, when the KAU is “limited” it indicates a knowledge gap in understanding the customer’s need. [2]

- Knowledge about Product Category (KAPG): this indicator includes a broad range of elements that define how is deep the knowledge of a company for a specific product. This involves the strategic relationship with stakeholders and market positioning. A product category can already exist or can be new. [2]

The Matrix consists of four quadrants, and each one suggests a possible project management model.

- Low Knowledge about Users/ High Category Knowledge

- Low Knowledge about Users/Low Category Knowledge

- High Knowledge about Users and Category

- High Knowledge about users and Low category knowledge

The matrix proposes a possible approach to the challenges that may arise in each quadrant. The traditional plan-based model (the Stage-Gate® only) is the perfect solution when the company has all the needed knowledge before the development process. [2] Generally, hybrid models are applied when some pieces of information are missing [2]. When the company has limited knowledge of customers’ habits, but the product concept is clear, a possible solution might be using a hybrid model. [2] Design Thinking techniques are implemented in the "Ideation" phase to empathize with the client and learn about his habits deeper than what a simple phase-gate model allows [2]. When the company wants to explore new markets, and a whole new product has to be developed, Design Thinking is used in the "Ideation" and the "Concept" phase, while Lean Startup gathers information about the unknown market in the "Business Case". [2] Finally, when the knowledge about the user is high but the company wants to develop a product that couldn’t be associated with existing categories, the Agile-Stage-Gate model is chosen, with agile (Scrum) elements in the "Development" and "Testing". [2] Iterations are useful to try different solutions and their impact on production or sales, like packaging or pricing.[2]

Overall, the Matrix provides some benefits. It is a powerful decision-making tool that fosters an objective evaluation of the developmental approach in each project stage. In this way, managers can reach an agreement on the methodology, avoiding later plan changes. [2] Moreover, the internal point of view of the matrix protects the company from uncertain financial estimations or inaccurate technological evaluations, supports managers in choosing what product to develop, and fosters innovation in the portfolio. [2] Finally, the matrix gives HR managers a broad overview of what kind of techniques will be applied to the NPD, thus supporting them in the resource selection process. [2] Those companies that cannot hire specialists in those areas could rely on “ad hoc consultancy”. [2]

Managing Agile-Stage Gate Projects: a portfolio perspective

The Agile-Stage Gate can be analysed on two different levels: the operational level, in which sprints are performed, and the strategic level, where the traditional stage-gate structure is kept to provide an adequate level of control on the project life-cycle.[12] Nevertheless, the two levels are not disconnected, but the adaptive, iterative approaches on the operational level impact how a project is evaluated at portfolio level. According to Cooper and Sommer [9], there are two common problems in new-product portfolio management: an overloaded pipeline, due to the incapacity of killing not-so-valuable projects, and the “lack of data integrity”(Cooper, Sommer, 2020)[9], which may also affect the go/kill decision-making process.[9] Consequently, the lack of reliable data in the “front-end homework” leads to poor evaluations in terms of the market’s needs, pricing, and final customers.[9] From this perspective, the Agile-Stage Gate keeps the existing structure and activities of the Stage. The difference from the previous model is the iterative and flexible approach to the development process, which through iterations allows increasingly reliable cost and market data to be collected, thus fostering a continuous evaluation/validation of the project.[9] Moreover, it encourages the engagement of management, because customer feedback can be reported to the senior management immediately, who can effectively evaluate the project in time and perform a go/kill decision before the project becomes too mature to be stopped. [9] However, integrating agile may bring out new challenges, because traditional project management methods for project prioritization can become senseless by the evolving nature of an agile project. [9] Cooper and Sommer, in their article "New-Product Portfolio Management with Agile"(2020)[9], suggest a set of metrics suitable to evaluate agile projects from an Agile-Stage-Gate portfolio perspective.

The Burndown Chart

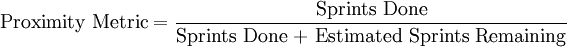

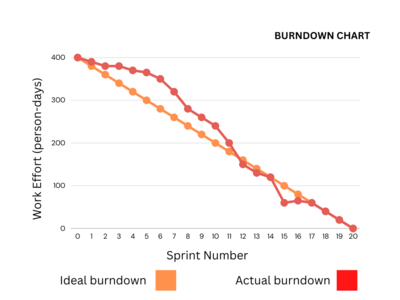

The Burndown chart is an agile tool to track team progress. Usually, the chart is applied to a single sprint, but in the ASG it can be used to track the whole stage. At the beginning of each stage, the tasks to be done in the stage are grouped in a project backlog. Moreover, the total number of sprints needed before moving to the next stage is approximated. The final result is a “dynamic”(Cooper, 2020)[9] Burndown chart, where sprints needed and tasks in the backlog change during the process. The team's progress can be evaluated by looking at the number of remaining sprints, or by calculating the Proximity Metric:[9]

The Productivity index

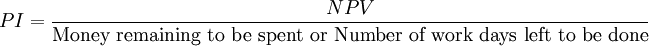

The Productivity Index (PI) seems to be suitable for agile projects. It highlights how much value is produced by the work done, and it is calculated over time. The PI is calculated as

An increasing PI Curve is a signal of a successful project. The PI also gives useful insights about overall productivity, thus fostering effective project prioritisation.[9]

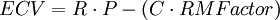

Expected Commercial Value (ECV)

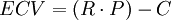

Among the existing tools, the ECV seems particularly suitable for agile projects, because it “provides a realistic financial model for handling incremental or stepwise investment in a new-product project, in the form of a decision tree approach that evaluates the investment a step at a time” (Cooper, Sommer, 2020)[9]. In ECV, it is possible to face two alternatives: one sprint and N sprints. In the first case,

,

,

were

- R = financial outcome expected from the project (usually presented as the current worth of the earnings expected to be received in the future)

- P = probability of success

- C= cost of undertaking the project

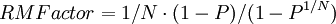

Starting from the assumption that each iteration requires the same amount of money to be invested, at N iteration the ECV is

where the RMFactor is

The probability of success can be estimated with the Delphi Method, with the help of some experts in that field. The ECV yields several advantages, such as taking into account the ambiguous nature of agile projects, the “incremental nature of investment decision” (Cooper, 2020), and the dynamic value of success probability. It can also be used in project prioritisation with the PI.[9]

Strategic Buckets: dynamic budgeting for dynamic portfolios

A more frequent evaluation of projects against portfolio requirements increases the number of projects that come in and out of the portfolio during the year. Therefore, budgeting activities should also follow the dynamic nature of agile. In the Strategic Buckets systems there are four key phases:

- projects are categorized based on certain criteria, decided by senior management.

- In each bucket, projects are ordered based on their priority, usually defined by using the PI

- Finally, resources are allocated in each bucket from the top-priority project.

- Projects that are at the bottom of the list should be killed or paused, waiting for resources from other projects. Inside a bucket, a portfolio manager can allocate resources from one project to another based on gate decisions, priority lists, and resource constraints.[9]

Critical Reflections on Status Quo and ASG Limitations

The Agile-Stage Gate is a broad concept, that touches various aspects of project management. Firstly, from a project perspective, implementing Agile within each stage, or in some of them, modifies the overall developmental approach of the project. The PMBOK® defines a developmental approach as “the means used to create and evolve the product, service, or result during the project life cycle”(PMI, 2021)[20]. The traditional approach to product development is predictive and plan-driven, and it aims to mitigate uncertainty through a deep front-end analysis. [20]. The method is particularly effective when project requirements are clear at the beginning of the project, so “scope, schedule, cost, resource needs, and risks” (PMI, 2021)[20] can be considered non-variable during the project life cycle [20]. This is also confirmed by the study by Cocchi et al.(2021)[2], where the traditional Stage-Gate® was applied in a relatively stable environment. For some projects, this approach might not be optimal, because project features can evolve and even change radically during the project, therefore strictly adhering to initial evaluations may lead a project to fail [3].In this context, according to the PMBOK®, the most suitable approach for those projects when “requirements are subject to a high level of uncertainty and volatility and are likely to change”(PMI, 2021) [20], is the adaptive one [20]. Thanks to iterations, the outcome can advance incrementally, driven by evolving requests. The Agile-Stage-Gate may also utilise a hybrid approach, described as a mix of predictive and adaptive approaches [20]. Adopting a hybrid developmental approach is suggested when it is possible to break down the deliverables into different modules, when different teams can work on different deliverables, or generally in uncertain situations where project requirements are not clear and may be necessary to evaluate different alternatives.[20]. When a product is created with an adaptive approach and implemented with a predictive one, overall it can be considered a hybrid approach [20]. This specific condition could be associated with those models where Agile is used in only some (and not all) stages, as happens in the study of Cocchi et al.(2021) [2]. Despite its advantages, the Agile-Stage-Gate model also has some drawbacks too. According to Salvato et al.(2020) [21], the study revealed that one of the possible negative consequences of the model was the increasing cost of the project. The author suggested that it could be related to three key factors:

- The merge of Agile and Stage-Gate® was not completely implemented, resulting in two-faced structures where the gating system and Agile worked together without harmony. In practice, the management continued to use the same old model without understanding the agile practices of the team, thus creating terminology obstacles at gate meetings and not completely recognizing the team’s needs. To have a smoother hybridisation process, more resources were involved [21]

- Frequent demonstrations with physical prototypes involved resources for weeks, with a negative impact on project costs. Prototyping methods, such as 3-D printing, digital modeling, and virtual prototyping, can be used to accelerate the prototype definition. [21]

- In the traditional gating model, resources can be shared among different projects. On the contrary, agile projects required a dedicated team, keeping the “off-peak time” not optimally used. In some cases, especially in “longer duration physical product activities”(Salvato et al. 2020), continuous sprints resulted in a high workload for team members, with detrimental consequences on their well-being. [21]

Annotated Bibliography

Robert G. Cooper, Stage-gate systems: A new tool for managing new products, Business Horizons, Volume 33, Issue 3, 1990, Pages 44-54, ISSN 0007-6813, https://doi.org/10.1016/0007-6813(90)90040-I

In this article, Robert G. Cooper explains in detail its Stage-Gate system, a plan-based approach to manage product innovation and deliver more and better products on the market. After a first introduction to the importance of product innovation, the article discusses why a gating system is necessary for product development, outlining its strongest points. Moreover, the article provides an example of the ideal 5-gate-5-stages Stage-Gate model, describing carefully the activities in each stage, the decision-making process, and the exit criteria at each gate. Overall, this article gives a broad overview of the Stage-Gate system.

K. Schwaber and J. Sutherland, "The Scrum Guide The Definitive Guide to Scrum: The Rules of the Game", Scrum.org, 2020.

Schwaber and Sutherland, in their Guide, describe completely the Scrum framework, a rugby-inspired project management model. Firstly developed in software development, its strengths have caught the attention of practitioners from outside the IT world, and today the approach is one of the most famous Agile methods for managing complex product development. in this Guide, all the key aspects of Scrum are presented: the underlying theory, its values, the key roles involve, Scrum events, and artifacts. In Agile-Stage-Gate, most of the implemented practices have their roots in Scrum, therefore the Scrum guide is a must-have when implementing the hybrid project management methodology.

Robert G. Cooper (2016) "Agile–Stage-Gate Hybrids", Research-Technology Management, 59:1, 21-29, DOI: 10.1080/08956308.2016.1117317

In this article, Cooper provides a general explanation of what a Hybrid Agile-Stage-Gate model is. The two models, the gating system and the Agile philosophy (especially in the context of the Scrum framework) are initially compared one against the other. Then, the author describes how to merge these two management models in the manufacturing world. Nevertheless, Scrum and Stage-Gate cannot be merged in their off-the-shelf version: some changes are needed to make the practices perfectly fit the context. Therefore, after describing the advantages of the hybrid mode, the author gives some recommendations on how to adapt the "Definition of Done" to different stages. Generally, the article is a good entry-level guide to better understand how the Agile-Stage-Gate may work in practice.

Nicolò Cocchi, Clio Dosi & Matteo Vignoli (2021) "The Hybrid Model Matrix Enhancing Stage-Gate with Design Thinking, Lean Startup, and Agile", Research-Technology Management, 64:5, 18-30, DOI: 10.1080/08956308.2021.1942645

The article contributes to the discussion about the hybrid model by providing a tool, the Hybrid Model Matrix, to help practitioners in choosing the right model for a given project. The Matrix is built upon two main factors, the knowledge the company has about the users and the knowledge about the product category( in other words, if the product can be associated with existing categories or not). Based on these two factors, each quadrant of the Matrix suggests the fittest project management model. The article is also a good opportunity to expand the concept of Agile hybrid models as a broader concept, as it shows how other Agile-related methodologies, such as Design Thinking and Lean Startup, can be applied to product development.

Robert G. Cooper & Anita Friis Sommer (2020) New-Product Portfolio Management with Agile, Research-Technology Management, 63:1, 29-38, DOI: 10.1080/08956308.2020.1686291

Managing new projects in an Agile-Stage-Gate environment requires to re-design the way managers evaluate and keep track of the initiatives. In the context of new product development of physical products, the article by Cooper and Sommer offers innovative guidelines to manage agile projects. In the first part, the authors introduce the common problems of new product portfolios and explain how agile practices may provide benefits to the process. Then, they discuss the emerging challenges of agile projects, providing some useful metrics to support a better and more dynamic evaluation.

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 EDWARDS, Kasper, et al. Evaluating the agile-stage-gate hybrid model: Experiences from three SME manufacturing firms. International Journal of Innovation and Technology Management, 2019, 16.08: 1950048.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 2.18 2.19 2.20 Nicolò Cocchi, Clio Dosi & Matteo Vignoli (2021) The Hybrid Model MatrixEnhancing Stage-Gate with Design Thinking, Lean Startup, and Agile, Research-Technology Management, 64:5, 18-30, DOI: 10.1080/08956308.2021.1942645

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 Robert G. Cooper & Anita Friis Sommer (2018) Agile–Stage-Gate for Manufacturers, Research-Technology Management, 61:2, 17-26, DOI: 10.1080/08956308.2018.1421380

- ↑ http://wiki.doing-projects.org/index.php/A_hybrid_consisting_of_Agile_and_Stage_Gate

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 S. J. Edgett, “Idea‐to‐Launch (Stage ‐ Gate) Model : An Overview,” Stage-Gate Int., pp. 1–5, 2015

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 6.8 Robert G. Cooper, Stage-gate systems: A new tool for managing new products, Business Horizons, Volume 33, Issue 3, 1990, Pages 44-54, ISSN 0007-6813, https://doi.org/10.1016/0007-6813(90)90040-I. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/000768139090040I)

- ↑ Cooper, Robert. (2008). Perspective: The Stage‐Gate® Idea‐to‐Launch Process—Update, What's New, and NexGen Systems*. Journal of Product Innovation Management. 25. 213 - 232. 10.1111/j.1540-5885.2008.00296.x.

- ↑ Cooper, Robert G., and Elko J. Kleinschmidt. "Stage-gate process for new product success." Innovation Management U 3 (2001): 2001.

- ↑ 9.00 9.01 9.02 9.03 9.04 9.05 9.06 9.07 9.08 9.09 9.10 9.11 9.12 9.13 9.14 9.15 9.16 Robert G. Cooper & Anita Friis Sommer (2020) New-Product Portfolio Management with Agile, Research-Technology Management, 63:1, 29-38, DOI: 10.1080/08956308.2020.1686291

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Felix J. Brandl, Moritz Kagerer, Gunther Reinhart, A Hybrid Innovation Management Framework for Manufacturing – Enablers for more Agility in Plants, Procedia CIRP, Volume 72,2018, Pages 1154-1159, ISSN 2212-8271, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procir.2018.04.022.

- ↑ White, K. R. J. (2008). Agile project management: a mandate for the changing business environment. Paper presented at PMI® Global Congress 2008—North America, Denver, CO. Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 ZASA, Federico P.; PATRUCCO, Andrea; PELLIZZONI, Elena. Managing the hybrid organization: How can agile and traditional project management coexist?. Research-Technology Management, 2020, 64.1: 54-63.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 Abbas, N., Gravell, A.M., Wills, G.B. (2008). Historical Roots of Agile Methods: Where Did “Agile Thinking” Come From?. In: Abrahamsson, P., Baskerville, R., Conboy, K., Fitzgerald, B., Morgan, L., Wang, X. (eds) Agile Processes in Software Engineering and Extreme Programming. XP 2008. Lecture Notes in Business Information Processing, vol 9. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-68255-4_10

- ↑ Laoyan, Sarah(2022) "What is Agile methodology? (A beginner’s guide)" 2022, https://asana.com/it/resources/agile-methodology

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.5 Cooper, R. G., & Sommer, A. F. (2016). The Agile–Stage-Gate Hybrid Model: A Promising New Approach and a New Research Opportunity. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 33(5), 513-526. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12314

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 K. Schwaber and J. Sutherland, "The Scrum Guide The Definitive Guide to Scrum: The Rules of the Game", Scrum.org, 2020.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Endres et al. 2022, "Sustainability meets agile: Using Scrum to develop frugal innovations", https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.130871

- ↑ Robert G. Cooper (2016) Agile–Stage-Gate Hybrids, Research-Technology Management, 59:1, 21-29, DOI: 10.1080/08956308.2016.1117317

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 REIFF, Janine; SCHLEGEL, Dennis. Hybrid project management–a systematic literature review. International journal of information systems and project management, 2022, 10.2: 45-63.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 20.5 20.6 20.7 20.8 Project Management Institute, Inc. (PMI). (2021). A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK ® Guide) – 7th Edition and The Standard for Project Management. Project Management Institute, Inc. (PMI). Retrieved from https://app.knovel.com/hotlink/pdf/id:kt012LZED4/guide-project-management/table-of-contents

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 Salvato, John J., and Andre O. Laplume. "Agile stage‐gate management (ASGM) for physical products." R&d Management 50.5 (2020): 631-647