The Five-Factor Model (OCEAN)

Contents |

Abstract

The Five-Factor Model (FFM), also called the OCEAN model or the Big Five personality traits, is a framework used in psychology as well as in personality tests in companies in order to establish ones personality according to a standardized framework. This tool was first proposed by Lewis Goldberg [1] in the early 1980’s and later developed between 1987-92 by Mr Costa and McCrae [2].

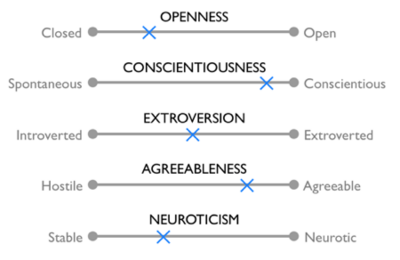

The objective of the five-factor model is to establish a psychological profile based on five character traits: Openness to experience, moral Conscience, Extroversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism [4]. For each of these five personality factors, the individual's score is calculated as follows: two opposing aspects of the predicted personality trait are placed in the form of a scale and a series of questions allows you to change to which of these two aspects and to what degree tends the personality of the candidate. For example, for the trait "Extraversion", the two aspects correlated with this trait are Enthusiasm on the one hand, and Assertiveness on the other. The test should determine towards which of these two aspects of a candidate's personality leans more [5].

The advantage of the five-factor model over other models commonly used in companies for profiling (eg MBTI, Enneagrams) [6][7] is that the diagnosis is individual and specific to each person. This allows for a personalized and unique profile for each person, instead of putting people in boxes.

The five factor model is especially useful in project management and team formation [8] because they make it possible to establish complementarities of profiles and to foresee the strengths and weaknesses (productivity, commitment, creativity) of an employee. Tests like the NEO-PI-R (Costa & McCrae, 1992) make it possible to establish the psychological profile of a person according to the OCEAN scheme [2].

Big Idea

Time of development

The need for the FFM came at a time where description of personality traits was becoming messy and non-understandable. The number of traits required to establish a personality could become overwhelming, and scientists as well as psychologists did not agree on the terms and their meaning, so that no proper framework could be popularized [9]. A simpler tool was therefore needed.

The first pioneering works began as soon as the late 1920’s, with the willingness for some researchers to use taxonomy to classify human personalities [9]. Taxonomy is the science of classification of things into separate boxes or categories [10]. This approach was triggered by the fact that the vocabulary was sufficient to describe, and furthermore self-describe one’s own traits.

Soon after, Raymond Catell started to shrink the thousands of terms used in the dictionary to describe personality to a few dozen [9][1]. His aim was to draw closer to a real and universal taxonomy for everyone to use.

In the early 1960’s, researchers such as Ernest Tupes and Raymond Christal or Warren Norman worked on refining the classification even more. Along with other researchers’ work on the matter, their findings led to Norman’s first categorization into five main personality traits which were at the time Extraversion (or Surgency), Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, Emotional stability versus Neurotism, and Culture [9].

However, their initial work was not popularized until the 1980’s. That is when Lewis Goldberg from the Oregon Research Institute took it upon himself to revamp the research and propose the first “Big 5” model [9]. The name big 5 was given to reflect on the inherent broadness of each one of those five traits.

Between 1987 and 1992, two researchers, Paul Costa Jr. and Robert Roger McCrae, developed the version of the model that we know of today, as well as one of the most popular test (NEO-PI-R) to assess ones personality according to the FFM framework [9][2].

Over the years, this theory has been developed and clarified in order for it to serve as a comprehensible template.

Change in development

The FFM was first developed in the 1960’s by two psychologists, Ernest Tupes and Raymond Christal, whose goal was to create a model capable of correlating someone’s personality with it’s academic achievement [9]. In that sense, the FFM was very much created in the fields of applied psychology and psychological trait theory. Now tests are conducted to assess personality traits in field way outside of psychology (management, job performance) [4].

Following Norman’s first classification (1967) [10], the last trait has been changed from Culture to Openness to experience. There has been a shift of focus from intellectual intelligence and brilliance to imagination and inner feelings [2].

Furthermore, the FFM bases its outcome one a set of adjectives (hundred to thousands of them) used by candidates to self-describe themselves. For each researcher that modeled the FFM, those adjectives could differ or imply different traits, so that the outcome of the tests would not exactly be the same from one version of the FFM to another.

The Tool

The OCEAN Tool stands for Openness to experience, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism which are the five personality traits of the model. To each one of those traits are associated two separate, but correlated aspects. The personality of a candidates will be determined by scaling its aptitudes between those two aspects, for each one of the traits. The aspects are labeled as follows: Intellect and Openness for Openness to Experience; Industriousness and Orderliness for Conscientiousness; Enthusiasm and Assertiveness for Extraversion; Compassion and Politeness for Agreeableness; Volatility and Withdrawal for Neuroticism.

In order to be more explicit, here is what those traits entail and imply [4] [5] :

- Openness to Experience. Openness to Experience includes active imagination, aesthetic sensitivity, attentiveness to inner feelings, a preference for variety, intellectual curiosity and independence of judgement. People scoring low on Openness (Intellect aspect) tend to be conventional in behaviour and conservative in outlook. They prefer the familiar to the novel, and their emotional responses are somewhat muted. People scoring high on Openness to Experience (Openness aspect) tend to be unconventional, willing to question authority and prepared to entertain new ethical, social and political ideas. Open individuals are curious about both inner and outer worlds, and their lives are experientially richer. They are willing to entertain novel ideas and unconventional values, and they experience both positive and negative emotions more keenly than do closed individuals. Studies have shown that scoring high or low on Openness to Experience can both be a good thing, depending on the given task. People who do not exhibit a clear predisposition to a single factor in each dimension above are considered adaptable, moderate and reasonable, yet they can also be perceived as unprincipled, inscrutable and calculating.

- Conscientiousness. Conscientiousness refers to self-control and the active process of planning, organizing and carrying out tasks. A conscientious person is purposeful, strong-willed and determined. Conscientiousness is manifested in achievement orientation (hardworking and persistent), dependability (responsible and careful) and orderliness (planful and organized). On the negative side, high conscientiousness may lead to annoying fastidiousness, compulsive neatness or workaholic behavior. High scorers (Orderliness aspect) are therefore well organized, hardworking and efficient. Low scorers (Industriousness aspect) might be messy, are not bothered by incompleteness and lack of accuracy, and are often distracted. Low scorers may not necessarily lack moral principles, but they are less exacting in applying them.

- Extraversion. Extraversion includes such traits as sociability, assertiveness, activity and talkativeness. Extraverts are energetic and optimistic. Introverts are reserved rather than unfriendly, independent rather than followers, even-paced rather than sluggish. Extraversion is characterized by positive feelings and experiences and is therefore seen as a positive effect. As a consequence, people scoring high (Enthusiasm aspect) are sociable, lively, seem confident, cheerful, and enjoy social interactions. People with low scores (Assertiveness aspect) are more reserved, calm, and less dependent on social life. However, in the Big Five system, extraversion is defined as an outward-looking activity. Extraversion does not describe, for example, how genuinely a person cares about others. It only takes into account the general level of outward-looking activity. Introverted people are not asocial, but simply need less stimulation and prefer to spend more time alone.

- Agreeableness. People who score high (Compassion aspect) are tolerant, gentle, kind, forgiving, pleasant, selfless, and helpful. Since it is very important for them to get along well with others, they have flexible opinions and prefer not to judge others. People with low agreeableness (Politeness aspect) are skeptical, stubborn, quarrelsome, self-interested, and blunt. People with low agreeableness also tend to defend their opinions, and to criticize others. People with high agreeableness are therefore usually appreciated more than people with low agreeableness. However, agreeableness is not always useful in situations that require making difficult or objective decisions. Studies have shown that a low degree of agreeableness can have many benefits for leaders and advocates.

- Neuroticism. Neuroticism is a dimension of normal personality indicating the general tendency to experience negative effects such as fear, sadness, embarrassment, anger, guilt and disgust. High scorers (Neurotic/Volatility aspect) may be at risk of some kinds of psychiatric problems. A high Neuroticism score indicates that a person is prone to having irrational ideas, being less able to control impulses, and coping poorly with stress. A low Neuroticism score (Stable/Withdrawal aspect) is indicative of Emotional Stability. These people are usually calm, even-tempered, relaxed and able to face stressful situations without becoming upset. A low score in neuroticism therefore seems to be an enviable situation. That is why some people rather use the term Emotional Stability instead of Neuroticism for this trait instead, as a high score would look like positive thing. However, candidates who score low to Neuroticism may also prove to be too reckless and too prone to underestimate the potential threats to their environment.

Multiple tests to asses ones personality using the FFM exist [9]:

- NEO-PI-R (the most used)

- International Personality Item Pool (IPIP)

- Self-descriptive sentence questionnaires

- Five Item Personality Inventory (FIPI), which is a very abbreviated rating form of the Big Five personality traits

What all this test have in common is the fact they base their grades on self-evaluation. This means that the candidate will describe what he or she thinks about him- or herself by answering a set of predetermined questions.

Two criticisms were then addressed against this rating system. First, for some of those surveys, the number of questions was not sufficient to properly determine the real personality of a candidate. Then, since those surveys rely on self-evaluation, some experts fear that the people undergoing those tests might distort their answers in order to paint a better picture of themselves. This idea is all the more likely if the test is part of the recruiting process, or if it plays a role in the acquisition of a job/role [13].

In order to deal with this latter issue, researchers have advocated for relative-scored Big Five measures, were the respondent is offered multiple answers, none of which being better or worse than the others . That way, the tests would be less prone to artificially good answers, that would paint the candidate in a brighter light than he actually is.

Purpose

As presented in some of the parts above, the FFM can prove to be a really handy tool for companies when it comes to creating efficient teams, with matching profiles. By determining the five personality traits of a respondent, criteria such as job performance, social interaction but also employability can be foreseen. For example :

- Openness to experience. Research have found that Openness to experience at work is related to consulting, training and adapting to change. However low scorers on Openness tend to be more successful employees, since they do not question every query so often [4] .

- Conscientiousness. This is the trait that has the biggest correlation with job performance. Some studies go even as far as stating that there is a correlation of 0,80 between reliability (part of the Conscientiousness trait) and job performance [5]. According to Sackett and Wannek (1996), those results can be attributed to conceptual relationship between integrity (at work) and Conscientiousness [9].

- Extraversion. Research have found that Extraversion scoring high on Extraversion is a good indicator for jobs such as salesmen and managers, where interactions are regular [4].

- Agreeableness. It is a significant indicator of job performance. Since an agreeable person will be altruistic and sympathetic to others, he or she will most likely thrive and make others thrive in occupations where teamwork or customer service are important. However, it can go the other way around too. An agreeable person will try to make everyone happy but will struggle making tough decisions or taking a controversial stand, even if it is necessary [4].

- Neuroticism. Neuroticism as a major correlation with job performance and is the second most important trait regarding employability (after Conscientiousness). Research have shown that Emotional Stability (the opposite of Neuroticism) is very sought out trait, because Neuroticism is inversely related to job performance [4].

The FFM is best thought of as a series of interconnected scales. Everyone will sit somewhere on each scale, but tests that use the OCEAN framework aim to determine the degree to which an individual shows the traits covered by each of the domains.

Many organizations use employee scores to determine cultural fit, in addition to building teams that have similar or complimentary personality traits. Some even take this a step further by providing staff with a summary of their results and advice on how best to communicate with employees with different personality types.

Outside of HR departments, marketers are the most frequent users of the OCEAN framework. Often combined with demographic or other targeting factors, the model is used to help understand audiences and what will likely appeal to them based on the commonalities within their personality profiles. Much has been written about subsets of personality types that marketers can target, in addition to strategies for doing so.

Application

There are mainly two ways in which the FFM can be used.

The first way in which the FFM can and has be used is establishing a link of predictability between personality and upcoming job performance. For decades now, researchers have been trying to assert the irrefutable correlation between some traits of the FFM and job performance indicators [9]. Different studies have shown a direct correlation between :

- Overall job performance and conscientiousness, emotional stability (inverse of neurotism), and extraversion [5]..

- Task performance and conscientiousness, emotional stability, and extraversion [5].

- Contextual performance and conscientiousness, emotional stability (inverse of neurotism), and agreeableness [5]..

It must be mentioned that only several studies have been used to write this articles and that slightly different outcomes could be found in other ones. However, some consensus such as the strong correlation between conscientiousness and all kinds of job performance indicators is something found in most statistical studies.

Another way in which the FFM can prove very useful is at personal level. For one’s job selection, knowing one’s strengths and weaknesses can lead up to better choosing of a career path. Meta jobs search engine have already put in place such tactics and big 5 traits tests in order to guide applicants toward job that will better suit their needs and personalities [14]. For instance, those who score high in :

- Openness to Experience: they can become tour guide or pilots, since those jobs require high incentive to discover new things and gather knowledge.

- Conscientiousness: they can become accountants or sales managers, since those jobs require a good attention to details and precision.

- Extroversion: they can become event planners or personal trainers, since those are jobs where activeness and teamwork are required skills.

- Agreeableness : Some example of jobs would be elementary school teachers or human resources specialist, since those are jobs were one must show a great deal of compassion and sympathy for others.

- Neuroticism : in this case, jobs that you shouldn’t consider are social worker or psychiatric nurse, that require a lot of emotional stability.

Limitations

However widespread this tool is today, limitations and criticism to its use still remain, especially in the job performance field. Since the research bases its findings on statistics and mostly draws conclusions thanks to statistical technics, the sample size and socio-economical context researchers use play a key role in the outcome of the experiments. For example a study conducted in a pharmaceutical company [4] showed no real correlation between personality assessment and job performance at first. Other studies mainly focus on one socio-economic type [5], or one gender, which will always tend to tweak the results. One can therefore wonder to which extent the result presented are universal.

Moreover, since the tests are mostly based on self-description, it is not always easy for anybody to have clear picture of there personality. Either willingly or not, people tend to draw a brighter or dimer picture of their character than it really is. This is particularly true in the case of job allocations, where people can know which questions trigger which outcomes, and thus get a better result regarding the job they are applying for.

Annotated Bibliography

- Rothman, S., & Coetzer, E.R. (2003). The Big Five Personality Dimensions and Job Performance. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 2003, 29 (1), 68-74.

This article is particularly relevant to understand what the big 5 traits are and what descriptions of one's personality they entail. Moreover, in this article is presented a real case study. This helps anyone understand how this tool and its analysis can be related to job performance predictions. More precisely, we are presented with the process of using statistics and statistical studies to deliver these outcomes.

- John, O.P., & Srivastava, S. (1999). The Big Five Trait Taxomnomy: History, Measurement, Theoritical Perspectives. University of California at Berkley, Department of Psychology.

These writing are a very complete descriptions of how the Five Factor Model became what it is today. It recounts every steps of its developments from the early stages in the 1920’s to the actual form it has today. It also introduces us to all the researchers that played a role, small or big, in the expansion and acceptation of this tool.

- Lado, M., & Alonso, P. (2017). The Five-Factor model and job performance in low complexity jobs: A quantitative synthesis. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 33 (2017) 175–182.

This article presents multiples studies trying to relate the outcomes of the FFM with job performance. This article is particularly interesting because it shows how the socio-economic environment influences the outcome of the studies. As a result, one can understand that there is no universal connection between the big 5 model and job performance, but rather correlations depending on the working environment and the backgrounds of individuals.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Goldberg, L. R. (1981). 'Language and individual differences: The search for universals in personality lexicons.' In Wheeler (Ed.), Review of Personality and social psychology, Vol. 1, 141-165. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 McCrae R.R., Costa P.T. (January 1987). 'Validation of the five-factor model of personality across instruments and observers.' "Journal of Personality and Social Psychology." 52 (1): 81–90. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.52.1.81. PMID 3820081

- ↑ PEATS-Redaktion (2018). ’Big Five - die Persönlichkeit in fünf Dimensionen’.(https://peats.de/article/big-five-die-personlichkeit-in-funf-dimensionen)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 Rothman, S., & Coetzer, E.R. (2003). 'The Big Five Personality Dimensions and Job Performance.' "SA Journal of Industrial Psychology", 2003, 29 (1), 68-74.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 Lado, M., & Alonso, P. (2017). 'The Five-Factor model and job performance in low complexity jobs: A quantitative synthesis.' "Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology" 33 (2017) 175–182.

- ↑ Myers, Briggs I., McCaulley M.H., Quenk N., Hammer A. (1998). 'MBTI Handbook: A Guide to the development and use of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator' "Consulting Psychologists Press, 3rd edition."

- ↑ Palmer H. (1991). 'The Enneagram: Understanding Yourself and Others in Your Life.' HarperSanFrancisco

- ↑ AXELOS (2017), 'Managing Successful Projects with PRINCE2, 6th Edition'. Published by TSO (The Stationery Office)

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 9.8 9.9 John, O.P., & Srivastava, S. (1999). 'The Big Five Trait Taxomnomy: History, Measurement, Theoritical Perspectives'. University of California at Berkley, Department of Psychology.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Norman, W. T. (1963).' Toward an adequate taxonomy of personality attributes: Replicated factor structure in peer nomination personality ratings.' "Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology", 66, 574-583.

- ↑ Lim, A. (2020, June 15). ’The big five personality traits’.Simply Psychology. (https://www.simplypsychology.org/big-five-personality.html)

- ↑ Is Be Wonders (2019). ’The Big 5 Personality Test’.isbewonders.com. (https://www.isbewonders.com/the-big-5-personality-test/)

- ↑ Block J (2010).'The Five-Factor framing of personality and beyond: Some ruminations'. Psychological Inquiry. 21: 2–25.

- ↑ Indeed (2020). 'Big Five Personality Traits: Finding the Right Jobs for You'. ([1])