The use of the A3 management process

Contents |

Abstract

This article will provide a general description theory and application of the A3 tool as a project manager. The tool is to be utilized by an assembled group of people [1] and is most commonly used for problem-solving by implementing the project management tool: PDCA (Plan-Do-Check-Act) management [1]. The tool is utilized by following a series of specific steps, such as describing the current condition, making a root cause analysis, deciding on countermeasures etc. and can be applied to almost any kind of problem across several industries [2]. The A3 tool was developed by Toyota in the 1960s [1] and its name derives from the A3 paper dimension, as this format was the largest faxable format, which enabled the Toyota employees to share their newly acquired knowledge[3].

In addition to the description of each step contained in the A3, this article provides a description of the mindset and way of thinking that one must approach each step with, and the A3 holistically. This is presented through seven elements that each address their own aspect of the mindset which, when combined, make up the entirety[2].

Although there are additional applications of the A3, this article focuses on the A3 as a tool for problem-solving. An example of another application for the A3 is e.g. for training and learning purposes with regards to root-cause analysis [1].

Lastly, the limitations of the A3 will be stated, by defining when, where and by whom the tool is not applicable. It is important to know that not every problem needs to be anchored and solved by the utilization of an A3 approach as this will take too much time[2].

The big idea of the A3

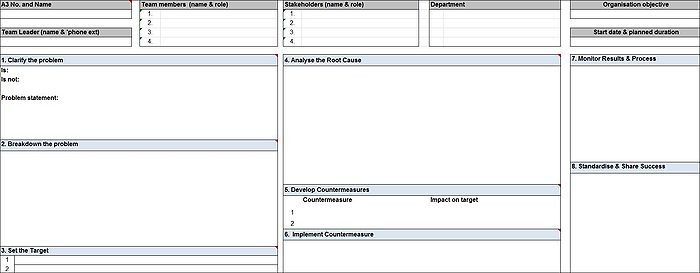

The A3 is a problem-solving tool that consists of, usually, 7 steps, which follow the PDCA cycle. Overall the steps can be divided into a "Plan" section, consisting of step 1-4, and a "Do-Check-Act" section, consisting of step 5-7 [2].

- Background

- Current condition

- Goal

- Root-cause analysis

- Countermeasures

- Effect confirmation

- Follow-up actions

The idea of the tool is to obtain a detailed understanding of both the problem to be solved and the setting (a machine, a process, an organization or a completely different setting) in which the problem exists. By obtaining a detailed understanding of how the setting functions, it inherently becomes easier to pinpoint what the problem is, where in the setting the problem is located, the potential cause(s) of the problem and finally how to solve the problem. When performing an A3 it is intended to get rid of the problem along with its cause for good, and not only implement solutions that will mitigate the problem leading to a re-appearance in the future.

A3's are data-driven, which means that no assumptions are to be made unless it is backed by data. However, the A3 format encourages short and precise formulations. A good way to accommodate this is by using a visual representation of data whenever it is possible. Using visual representation enables participants to quickly get an overview whenever the A3 is being re-visited.

It is important to mention that it is not advised to perform an A3 single-handedly as the idea of the tool is to include multiple points of view in order to grasp and understand the total overview of both the setting as well as the problem itself [2].

The following section will provide a description of each step contained in the A3 process.

1. Background

The purpose of the background section is to provide the participants with a sufficient amount of background data in relation to why the targeted problem is a problem, and why the project team needs to solve it. It is essential that the background of the problem is tied to a goal of the company [2], as one might find oneself wasting time trying to solve a problem, which might not be perceived as a problem from the company perspective.

When formulating the background of the problem, it is essential that one considers what kind of audience it is presented to. If the audience is characterized by people who are more detailed and technical, they might be more interested in the technical background data, where an audience consisting of people from management, might be more interested in what costs are tied to the problem [2].

2. Current condition

Setting up and presenting the current condition is one of the most important steps in the A3. The current condition functions as the baseline, and therefore decisions are often based on what the current condition is stating about the problem. It is therefore important to state the current condition objectively, precise and backed by data. As for the Background section, understanding the composition of the audience is key.

Usually, problems fail to be solved as a result of either not understanding the current condition sufficiently, or underestimating the importance of this specific section[2].

3. Goal

Defining a goal of the A3 means that it is established at what level of results the problem can be considered solved. Sometimes it is easy to establish the goal if the problem only exists as either solved or unsolved and then the obvious goal is to solve the problem fully. However, sometimes it can be a problem which can be partly solved, e.g. by reducing the frequency of occurrence, if it is a repeating problem. Here, it is important to decide when the results will be satisfactory. It is important to try and set up the goal as a measurable quantity, as this will make it easier to conclude whether your result is a success or not. Depending on the type of problem, several measurable quantities might be necessary to set up, as the result of achieving the scoped goal might have an undesired, negative impact on other factors. Therefore, it is important that your current condition is well-understood, so the entirety of the problem is grasped and the correct goals can be set up[2].

4. Root-cause analysis

The root-cause analysis is where the problem is finally taken on. As the name indicates, it aims to identify the root cause of the problem. The common mistake in a root-cause analysis is to solve the problem at a too high level, meaning that the underlying problem is not solved, and the problem will most likely re-appear in the future. A root-cause is the very thing causing the problem, and therefore a good rule-of-thumb is to ask yourself: "If I fix this (the plausible root-cause), is the problem likely to occur again?". A very popular tool for identifying the root cause is the 5 Why's (or the 5 times why)[2].

5 Why's

The 5 Why's is essentially a tool to help the applier in tracing down the source of the problem. This is done by stating the overall problem you want to solve, and continuously ask the question "why is this the case?". After having performed the first "why?" a new problem will occur as the source of the first problem, and the same question is then asked: "why is this the case?". Having done this five times, the initial problem is broken down into five levels, each going deeper than the previous, and the root cause may be identified. However, it is not always the case that the root cause is identified in the first attempt, and therefore the 5 Why's is often beneficial to repeat several times[4].

Another useful tool to identify the root cause is the Fishbone Diagram.

Fishbone diagram

The Fishbone Diagram (also known as the cause-and-effect diagram) is a tool that states the problem and seeks to identify potential causes to the problem, within separate categories. Typical examples of the categories could be Man, Machine, Material, Method, Process, Suppliers etc. Once the categories are established, the dedicated team performs a brainstorm on what might cause the problem, using the categories as a baseline. Once potential causes have been listed, the most likely ones are investigated and evaluated based on data gathered. Has the root-cause not been found the process starts anew while utilizing the learnings achieved by the unsuccessful investigation. Alternatively, The Fishbone diagram can advantageously be followed by a 5 why's analysis, as the Fishbone diagram is a broad tool, identifying multiple causes, while the 5 why's is great at providing a deeper understanding of a selected potential cause[4].

5. Countermeasures

Once the root-cause analysis has been performed and a root-cause has been identified, it is time to step 5 in the A3 tool: countermeasures. Countermeasures seek to eliminate the root cause of the problem. The countermeasures section on an A3 is usually presented by a list with the countermeasures which have been executed are posted. A countermeasure on the list should contain information on: "What is the cause of the problem?", "How has the countermeasure been investigated or implemented?", "Who is responsible?", "When was it implemented?" and lastly " What was the result, or what learnings were achieved?". Included in the list, it should also be clear in what order the countermeasures have been implemented[2].

6. Effect Confirmation

It is important to measure the impacts of the countermeasures, as this is an indicator of whether the countermeasures are working as intended and reducing the problem or if it is not working as intended and does not provide the intended effect. The Effect Confirmation is the section that makes sure of just that. Often, countermeasures are being implemented but the impact they cause are being neglected. To really confirm that the countermeasures have delivered a successful contribution to the problem, they must be verified by data. For this section, it is important that an effect confirmation plan is prepared, stating how the impacts of the countermeasures are to be measured and who the responsible persons are.

Should the results of your countermeasures not turn out as expected; perhaps the countermeasures did not affect the causes they were intended to affect, it is a good idea to initially discuss the reason for this with the established team. Consider going through the A3 from the beginning to the end, and evaluate if the followed steps make sense, or an alternative path might need to be considered. An A3 is an iterative process, and seldom are the specific steps only visited once upon completion[2].

7. Follow-up Actions

The seventh and last section of the A3 is reserved for reflection on the outcome and learnings. An example of a reflection could be if there are any other locations, processes or machines that the outcome of the A3 could also be exploited. Another possibility that is more closely related to the follow-up action headline would be to investigate some of the other potential causes for the problem, or even to dig deeper into the root cause itself. Often it is possible to reach deeper levels of a root-cause than the level one can actually do something about. It may be a supplier who is responsible for levels deeper than the one chosen to act on. Therefore, as a part of the follow-up actions, this may be essential to look further into, as it will probably also create value to the supplier[2].

Limitations of the A3 tool

Prior to utilizing the A3 tool, one must grasp the A3's limitations.

Even though the A3 is a very general and broad tool that can be utilized almost everywhere using the correct approach, there are limitations. Numerous companies have in their pursuit of success in problem-solving tried to implement the A3 into the company structure, but ended up short compared to the results achieved at Toyota. The probable reason for the failed implementations of the A3 is to be found in the mindset towards the approach of an A3. Companies failing to implement the A3 are often focusing on solutions that show immediate results. This often results in problems getting fixed on a short term basis and thereby continue to re-appear, instead of focusing and dealing with the actual root cause of the problem. Understanding and following the mindset and approach of an A3 is just a great success factor as the ability to follow and fill out each section. In conclusion, one must first familiarize themself with the A3 thinking, before rushing into the problem-solving process. As formulated by Durward K. Sobek II and Art Smalley, there are seven elements of A3 thinking one should reflect upon before they embark on the actual A3[2]:

Logical Thinking process

Being able to think and approach a problem logically is key when working with the A3. The ability to discern the difference between cause and effect is essential to make qualified decisions. The logical thinking process is embodied by the ability to investigate during the A3 using a mix of discipline and scientific methods. Furthermore, it is important to evaluate the potential causes for the initial problem, and investigate which of the problems weigh the most and will have the greatest potential of making a severe impact[2].

Objectivity

People are inherently subjective. As a result of this, the proper solution for a problem can be many different things, depending on who you ask and what their daily tasks are. Sometimes, the focus even fades from the problem itself and becomes a focus of who to blame for the problem. When working with an A3, the subjectivity of the persons involved must be discouraged by demanding facts and data to substantiate the claims. In this way, the suggestions backed by facts and data cannot be argued and affected by the participants' emotional tendencies, which create an alignment within the group of participants. With that said, it can still be important to provide creative and out-of-the-box suggestions, as this can lead to break-throughs in the problem-solving progress, however, it is important that the suggestions are subsequently backed by data[2].

Results and process

Using the A3 as a problem-solving tool, it is important to understand that the process to achieve a result, is just as important as the result itself. It can often be tempting to make assumptions on what the best solution to a problem is, and then directly implementing it. However, this approach often leads to rash decisions, as the understanding of the problem environment is not sufficient, which might lead to a low-quality solution. Taking the time to investigate the problem and follow the seven steps provided by the A3 will often lead to a mitigation of the root-cause, instead of short term problem solving as previously mentioned. In this section, it is also important to remind you of what was previously mentioned in the article: not every problem is suitable for an A3 analysis. Assessing which problems can benefit from an A3 and which cannot is also a highly valued skill[2].

Synthesis, distillation, and visualization

Be brief, be precise and be visual. Often, important information is hidden within pages of pages in a report but in an A3 it is encouraged to be a brief and precise as possible, while still delivering the essential information. A good way to do this is by using graphical presentation wherever possible and useful. The graphical presentation can e.g. be a picture, a process diagram, a graph or whatever fits the information that is to be presented. The graphical representation provides a quick and efficient overview of what is worth to display, and the A3 can thereby be quickly brought up to speed when returned to[2].

Alignment

Alignment when working on an A3 refers to the alignment of the people affected by the decisions and outcomes of the A3. In other words, the stakeholders. It is important that alignment is sought out, as people are more likely to come together in collaboration to help solve the problem and creating a change, instead of working against the change. As alignment and consensus from all parties involved are a rare occurrence, it is important that the rationale for not realizing the affected party's vision is presented and explained[2].

Coherence within and consistency across

Keeping coherence within the A3 and consistency across the organization is key to achieve an effective problem-solving process. It should always be aimed to be coherent when working on the A3, meaning that the focus is kept on the goal. Sometimes, solutions are proposed which might not speak into the overall company goal or an implementation plan of a decided solution leaves out critical aspects of the solution itself. The order of the steps in the A3 try to enforce the coherence, however, it is the participants' responsibility of making sure this is also what is really happening. The consistency across refers to across the organization. Making sure the overall approach of an A3 is similar no matter what department or organization level you might find it in, ensures that the knowledge sharing and participation of an A3 can be utilised by any employee at any level in the organization[2].

System viewpoint

The system viewpoint means that the participant of the A3 is able to see the bigger picture of the potential implementations to be made. A positive effect in one department can be a negative effect in another department. Therefore, being able to see the problem from multiple perspectives and to evaluate these is paramount. At the end of the day, the final solution should benefit the company in its entirety and not only the department facing the problem. Assessing the actions or implementations based on the scale of the impact along with the affected parties is therefore essential[2].

Having these seven elements evaluated and reflected upon, it can be argued that you are well on your way to participating in or writing your own A3.

Application of the A3 tool

The beauty of the A3 is that everyone with the right approach and alignment on the seven elements of A3 thinking can participate or write an A3. Another reason for the section describing when it cannot be used being displayed first is that it is easier to list when the A3 cannot be used instead of when it can be used. However, the A3 is not a magic tool that will do the work for you. A poorly executed A3 is not much worth, as it is the thinking provided and learnings gained throughout the A3 that creates the value[5]. Another important perspective is perhaps not so much when an A3 can be used, but perhaps more when an A3 should be used. An A3 can provide great value when it comes to problems that are complex and need investigation in order to identify the root cause and potential solutions but may bureaucratize problem-solving when it comes to smaller, less complex problems. Therefore, as previously mentioned, assessing whether an A3 is necessary is important, as the tool only can provide value when applied under the right circumstances, such as a complex problem, involving multiple areas of investigation [6] [2].

Annotated Bibliography

- D.K. Sobek, Art Smalley (2008), "Understanding A3 thinking", Productivity press

- Provides the foundation of the idea of the A3 itself. An author of this book has been with Toyota for many years as an employee, which offers great insight into the thoughts and approach towards the A3 from the creators themselves.

- Rodrick A. Munro, Govindarajan Ramu, Daniel J. Zrymiak (2015), "The Certified Six Sigma Green Belt Handbook", 2nd Edition, ASQ Quality Press

- Offers a great and detailed description of the root cause analysis process which is a big part of the A3 and its utilization, along with other project management tools related to lean management.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 William C. Schwagerman III, Jeffrey M. Ulmer (2013), "The A3 Lean Management and Leadership thought process", The Journal of Technology Management

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 2.18 2.19 2.20 2.21 D.K. Sobek, Art Smalley (2008), "Understanding A3 thinking", Productivity press

- ↑ Stijn Slootmans (2018), "Project Management and PDSA-Based projects", Springer International Publishing

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Rodrick A. Munro, Govindarajan Ramu, Daniel J. Zrymiak (2015), "The Certified Six Sigma Green Belt Handbook", 2nd Edition, ASQ Quality Press

- ↑ Christoph Roser, "The A3 Report – Part 3: Limitations and Common Mistakes", The A3 Report – Part 3: Limitations and Common Mistakes, last visited: 2021-02-28

- ↑ Michael Ballé (2017), "WHEN SHOULD WE DO AN A3 OR USE A DIFFERENT PROBLEM-SOLVING TOOL?", WHEN SHOULD WE DO AN A3 OR USE A DIFFERENT PROBLEM-SOLVING TOOL?, last visited: 2021-02-28