Theory of Constraint

*Disclaimer: The articles are created by DTU students. As part of the course, students are introduced to knowledge related to IP rights, plagiarism and copyright infringement. Additionally, the articles are a product of critical engagement of students with the literature review, and their aim is to contribute to the Project Management holistic field of science. If you discover any potential copyright infringement on the site, please inform thereof by sending an email to ophavsret@dtu.dk.

Developed by Jane Lynge

The underlying assumption of Theory of Constraint (TOC) developed by Eliyahu M. Goldratt is that the performance of a system constraint will determine the performance of the whole system or organization. A constraint is anything that limits or prevents higher system performance to reach its goal. The constraint is the weakest link in the chain. A Five Focusing Steps methodology can be used to identify and eliminate constraints in an organization and it can be a tool for continuously improvement in the same.

TOC is originally applied in manufacturing and scheduling where the speed of a constraint sets the pace of a process in a production line. However TOC has evolved from a production schedule method to a project management methodology that can be used to schedule resources in the execution of project. Critical Chain Project Management CCPM has a focus on how project managers deals with human behaviour. The technical aspects of CCPM are to focus on the critical areas by identifying the critical chain and to insert buffers at appropriate points in the project network.

The drawbacks of TOC and CCPM seems to be limited research in the field and the acceptance of the employee using this methodology.

Contents |

Overview

The methodology Theory of Constraint (TOC) was introduced by E. Goldratt in his book “The Goal” in 1984 (REF5), but the roots of TOC can be traced back to the development of the software Optimized Production Technology (OPT) in the late 1970s (REF6, page 648). In the middle of the 1980s Goldratt introduced TOC in project management, where he identified the constraint of a project to be within the scheduling of resources.

Assumptions

A main assumption in TOC is that the primary goal of a business is to “make more money now and in the future without violating certain necessary conditions”. (REF6, p 649) To obtain this goal according to TOC an organization can be measured and controlled by three measures: Throughput, operational expense and investment (originally called inventory).

Throughput, which is the most important measure according to Goldratt, measures the rate at which an organization generates money through sales. Investment is the money tied up in physical things like inventory, equipment, real estate etc.) Whereas operating expense is money spent to create output other than variable costs (capacity cost, taxes, utilities etc.)

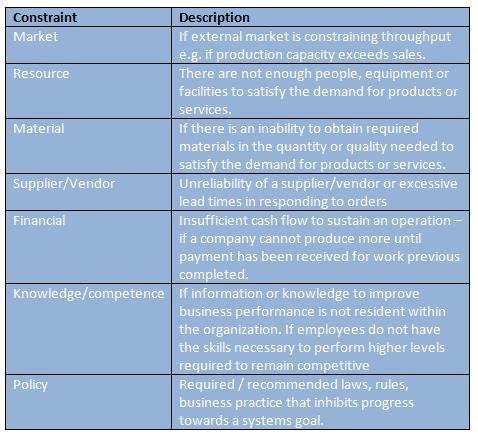

Another assumption in TOC states that every business has at least one constraint. A constraint (in manufacture often called a bottleneck) is anything that prevents an organization from making progress towards its goal of earning money. See a list of constraints in below table 1

Constraints are not always easy to identify. Often they can be non physical or difficult to measure. In many cases a policy is most likely behind a constraint from any of the other categories mentioned in table 1. For this reason TOC assigns a high importance to policy analysis. (REF3, p7) En example is a strategy of an organization to get closer to the customers in the local geographical markets. However if the distribution set up of the organization is not supporting roll out of this awareness strategy it could be identified as a constraint to obtain the strategy.

Two perspectives of TOC

TOC can be seen from two perspectives: the perspective of a business system and the perspective of an on going improvement process itself (REF6, p 649).

TOC as a Business System

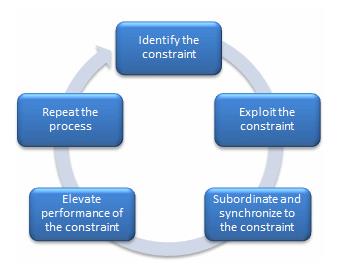

Seen from a business system viewpoint TOC emphasizes change process implemented in three levels: the mind-set of the organization, the measures that drives it and the methods employed within the organization (REF6, p. 649). From previous section we know that according to TOC in very process there is a constraint and that the total throughput can only be improved when the constraint is improved or eliminated. Accordingly, Goldratt introduced a “Five Focusing Steps” methodology to identify and eliminate constraints as well as being a tool for continuously improvement in the organization. See figure 1.

The first step of Goldratts methodology is to IDENTIFY the current constraint. The constraint is the single part of the process that limits the rate at which the goal is achieved.

In the next step EXPLOIT quick improvements of the throughput of the constraint are carried out by using existing resources. Processes are improved or otherwise supported to optimize capacity without using major expenses. Also it is important in this step to make the organization aware of the constraint and its effect on the performance of the organization.

In the step SUBORDINATE all the non-constraint activities in the process are reviewed. This is to make sure that the non-constraints are aligned with or paced to the speed or capacity of the identified constraint. In other words the non-constraints should avoid doing unneeded work.

In the ELEVATE step further actions are to be taken, if the constraint still exists. The aim is to eliminate the constraint from being a constraint, and actions are continued at this step until the constraint has been "broken". In this step some investments or reorganization might be considered necessary in order to eliminate the constraint.

Once the constraint is broken the organization move to step five REPEAT which means that it is time to repeat the continuous cycle of improvement. The performance of the system is re-evaluated by searching for and addressing a new constraint.

Drum-Buffer-Rope

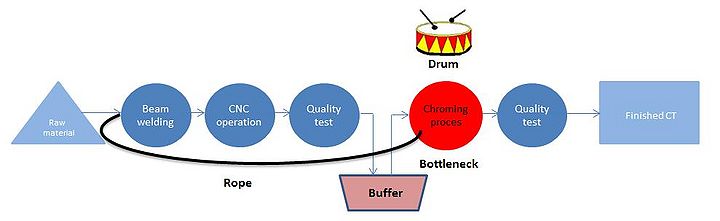

Goldratt introduced different tools to describe and analyse the process and to develop a constraint schedule to manage buffer inventory in an organization. One of the most known is “Drum-Buffer-Rope” (DBR), which is a method of synchronizing a production to the constraint while minimizing inventory and work-in-process. Figure 2 illustrates an example of DBR.

In above example we have a production of CT (chilling tubes). In the production of these CT tubes the constraint (bottleneck) is identified to be the chroming process. To protect the constraint a buffer is created around the CT tubes. The buffer in this example is to secure that a certain level of CT tubes is ready to be chromed. All other operations are subordinated to secure that the buffer is never idle. The drum is the constraint (chroming process) and the speed at which the constraint runs. The drum sets the beat or the pace of the process which determines the number of finished CT tubes and - in the end - determines the throughput.

The rope is a signal generated by the constraint (the chroming process) indicating that some CT tubes have been consumed (made ready for chroming) and this triggers the start for new CT tubes to be processed in the process flow lying ahead of the constraint.

TOC as an On-going Improvement Process

If you look at TOC from the perspective of an on-going improvement process TOC suggest that an organization must answer three fundamental questions concerning change in order to accelerate its improvement process:

- What needs to be changed? How to identify the weakest link (the constraint) in the organization?

- What should it be changed to? How can the organization be strengthened by developing good and practical solutions around the constraint?

- What actions will cause the change? How should the organization implement the solutions?

Goldratt and his team developed a whole set of techniques known as the Thinking Process to address these questions - below two examples:

a. The Strategic Current Reality Tree Technique which identifies the root causes behind the mismatch between where the organization is today and where it wants to be at the end of the planning horizon (desired stage).

b. Evaporating Clouds is used to put focus on the root causes of the gaps identified under a. This technique can root out and resolve the conflicts behind the root cause as well as the resistance towards change in the organization.

Applications

The Five Focusing Steps methodology have mainly been applied to manufacturing and supply chain solutions as also illustrated in previous examples. But especially the Thinking Process tools have also led to TOC applications being used in the field of marketing and sales for example to identify product mix solutions.

TOC in Project Management

In 1997 Goldratt extended the production application of TOC to projects. He identified the constraint of a project to be “the sequence of dependent events that prevents a project from completing in a shorter interval” (REF7). According to Goldratt resource and activity dependencies determine the critical chain in a project. This is because the scheduling of resource and activity has a big impact on project cost and scope.

- If schedule increases with fixed deliverable scope - the cost will usually increase.

- If scope increases with fixed cost (or resources) - the schedule tends to increase.

Because the resource constraint is identified to be a significant project constraint, the TOC method for project planning considers this. The critical chain therefore includes the resource dependencies of the overall longest path/constraint of a project. It may be, however, that the critical path/constraint change if for example other paths experience delay.

TOC applied for Project Management is named Critical Chain Project Management (CCPM) methodology and the Five Focusing Steps methodology is adapted to CCPM. For CCPM first step IDENTIFY focus on identifying which constraint/critical path in the project that limits the speed of the project deliverable and hereby the achievement of the goal.

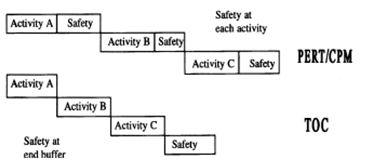

In the EXPLOIT step a "low-risk" activity duration of the project is estimated. Here the estimators have to understand the critical chain methodology so that the solicited estimated "average" times assume that everything will go after the plan. This also requires that the participants devote 100% of their time to the project. As illustrated in figure 3 below the critical chain use reduced activity duration estimates compared to PERT-CPM. In other words it means that the critical chain constitutes the constraint that determines the earliest date that a project can finish. Monitoring the progress along this critical chain is crucial, because it will reflect the progress of the entire project.

The SUBORDINATE step look at the non-critical chain paths. CCPM uses “late start” for all non-critical project activities. This makes sense because feeding buffers will protect the critical chain from delays occurring in non-critical chain activities. You can say that feeding buffers protect against variability to protect the overall project form late completion of the feeding paths.

Also a project buffer is established in the end of the final activity to protects against variability and uncertainty that might impact the critical chain. CCPM project plans provide data for the start of activity chains only as well as data at the end of the project buffer. This is to enable the project team to focus on completion of the project as soon as possible.

In the ELEVATE step of CPPM ...... Elevate Activity Performance by Eliminating Multitasking Eliminating “fragtional head counts” is a primary consideration in planning a critical chain project. REPEAT Project managers in CCPM update the buffers as often as needed by continously asking each of the performing activities how many days they estimat to the completion of their activity. As long as the resources are working on the activities with the CCPM activity performance paradigm it is positiv regardless of the actual duration

Advantages and Limitations of TOC

Advantages of TOC

- TOC has been compared with established operational management tools in more studies. For example as capacity scheduling in a production line TOC is an easy way to identify how many items can be produced within a certain period of time. TOC can ensure an even and efficient pace in a production taking an identified constraint into consideration.

- As an improvement methodology TOC produces positive effects on flow time of a product or service through a system. TOC used in improvement processes requires limited intimate knowledge of data analysis. Only a few people in an organization need to understand the elements of the system in order to implement this method. This means that a TOC effort in this context can be localized with minimum involvement from the workforce in e.g. a manufacturing company. (REF8, p 76). As a consequence of this you could argue that especially organizations with hierarchical structure and centralized knowledge would value the TOC approach.

- Think Process tools e.g. the reality trees are examined to be particular useful to address non-physical constraints such as wrong policies or inconsistent performance measures according to a study by Chaudhari and Mukhopadhyay where interactions among the supply chain members of a service industry was analysed. (REF6, p 654). This means that the thinking process tools are very useful to systematically cover whole process from identifying and connecting various undesirable effects using effect-cause diagramming principles to diagnose what in a system needs to be changed. And also these tools can verbalize inherent conflicts and come up with ideas which can be used to resolve core problems without crating new undesirable effects (REF6).

- The Five Focusing Steps as well as the Thinking Process presents a variety of tools to approach different problems in an organization or in a project. For example to solve a relative simple product mix problem the TOC tools combined in different ways can provide a flexible and synergic approach to identify different solutions and solve a specific problem.(REF6, page 652 and 653).

- TOC applied for Project Management CCPM is differentiated from traditional project management approaches like PERT and CPM, because CCPM recognizes and accounts for human behaviours to ensure on time completions of project activities. CCPM seeks to avoid student syndrome of waiting until last minute to begin work on a task. Also it deals with the problem of multitasking - when more project participants are assigned to more tasks and switch back and forth causing delays.

- CCPM removes protective time in the resource schedule of a project which means that the participants time buffer or "protective pad" is removed from every activity of the project. This reduces the accumulated protection buffer of the entire chain. In stead CCPM inserts buffers (critical resources) in key locations in the chain. CCPM focus on the longest sequence in a project and considers both dependent, sequential activity links and resource links. Whereas The Critical Path used in a PERT/CPM approach only reflects the sequential linking of dependent tasks. (REF3, p19).

Limitations of TOC

- A major obstacles to TOC (as well as Lean and Six Sigma)as an improvement methodology is that the TOC methodology address management theories as a secondary issue. TOC does not address the general theory of management or the policies of an organization (REF8). Change processes challenge existing ways of doing things in an organization, and policies and organizational values might have to be revised. TOC does not take into account that earning money is not always the only purpose of an organization.

- When used as improvement process with low work force involvement, you could argue that TOC has some drawbacks. If an employee is only briefly informed and not involved in the TOC process he/she might feel less motivated (engaged). Work force involvement according to Dave Nave is vital for successful implementation of TOC (REF8, p. 76).

- Gupta (REF6, page 658)in his article about Constraint Management concludes that TOC has a potential to be established as a useful production management theory as it is widely applicable across the production function, however the theory of TOC has not been empirically developed and tested which is required to be accepted as a general theory.

- Even though the concept of CCPM with buffers whether project, feeding or resource can easily be added to existing project management approaches the critical aspect in CCPM is that its success depends on the project participants acceptance of the CCPM premises (e.g. the cut in activity times) as well as the project managements understanding of the psychology of the project team.

Annotated Bibliography

REF1

Bicheno, John, et (2009), The Lean Toolbox – The Essential Guide to Lean Transformation, Fourth Edition, Judge Business School, University of Cambridge, PICSIE Books, UK

This book gives the reader an overview of lean concepts and techniques and places the TOC contributions of Goldratt into the framework of improvement programs. The TOC methodology is presented showing the synergy between TOC and Lean.

REF2

Boyd, Lynn, et al (2004), Constraint Management – What is the theory?, University of Louisville, USA, International Journal of Operations & Production Management, Vol. 24 No. 4, 2004, pp350-371

The purpose of the article by Boyd et al is to propose a throughput orientation, discuss a model for throughput orientation as well as suggesting hypotheses that might be empirically tested to establish TOC and CM as a theory not only recognized by practitioners, but also by theorists and researchers. This article supports the idea that more research within the CM/TOC area is needed if they are to be recognized as theories

REF3

Dettmer William (2000), Constraint Management, Quality America. Inc. 2000, Chapter from updated 2000 edition of The CQM Guide written by Pyzdek, Thomas originally published in 1996.

This paper describes and illustrates the key element of TOC, its development and another valuable asset of the TOC toolbox called critical chain. Critical chains constitutes the application to onetime projects of the same principles that DBR applies to repetitive production. CCPM is presented in this paper as well.

REF4

Figure 2 is inspired by the Drum-Buffer-Robe illustration in below mentioned homepage. The product (CT tubes) is taken from report made by Jane Lynge about S&OP Planning of Chilling Tubes as SPX Flow Technology. http://www.marris-consulting.com/en/Using-Theory-Of-Constraints-to-boost-Lean-programs-158.html?aMotsCles=a%3A1%3A%7Bs%3A0%3A%22%22%3Ba%3A1%3A%7Bi%3A0%3Bs%3A3%3A%22TOC%22%3B%7D%7D

REF5

Goldratt, Eliyahu M, et al.(2014), The Goal – A Process of Ongoing Improvement, The North Rivel Press Publishing Corporation, Fourth Revision Edition.

In 1986 the first version of “The Goal” was published. The book was written in a fast-paced thriller style about a plant manager working hard to improve performance in his factory. The book, set up as a popular novel, explains in a practical way how the plant manager saves his factory by learning about and implementing TOC principles. This is that historical foundation for TOC.

REF6

Gupta, M (2003), Constraint management – recent advances and practices, International Journal of Production Research, 2003 Vol. 41 no. 4 pp 647-659.

This article is about Constraint Management and system thinking because an organization succeeds or fails as a complete system. The TOC principles and concepts in recent years have been extended into a CM application also supporting TOC within project, program and portfolio management.

REF7

Leach, Larry P. (1999), Critical Chain Project Management Improves Project Performance, Quality Systems, 1577 Del Mar Circle, Idaho USA

This article describes the theory and practice of TOC use in project management also called Critical Chain Project Management (CCPM).CPPM differs from critical path method by including resource dependencies and improving the project plan by inserting buffers at the end of the activity chains. The article also adapts the Five Forcing Steps from TOC info project management.

REF8

Nave, Dave, (2002), How to Compare Six Sigma, Lean and the Theory of Constraints – a framework for choosing what’s best for your organization, Quality Progress, March 2002.

This article is about selecting the best improvement methodology in an organization and the author discuss the basics of the improvement methodologies Six Sigma, Lean and TOC; the concepts and effects as well as the similarities and differences. This is relevant for this TOC paper in the sense that organizations thrive to improve their business system also in their execution of projects, programs and portfolios.