Eisenhower Matrix

By Stefan Susic

Contents |

Abstract

The Eisenhower Matrix is a tool for organizing and prioritizing the severity of task’s Urgency and Importance. This method is named after Dwight D. Eisenhower, the 35th president of the United States, who was known for being a highly effective leader both in the military and in Government. In newer times, author of “7 habits of highly effective people”, Stephen Covey, has given his own interpretation of Eisenhower method, also known as the Time Management Matrix.

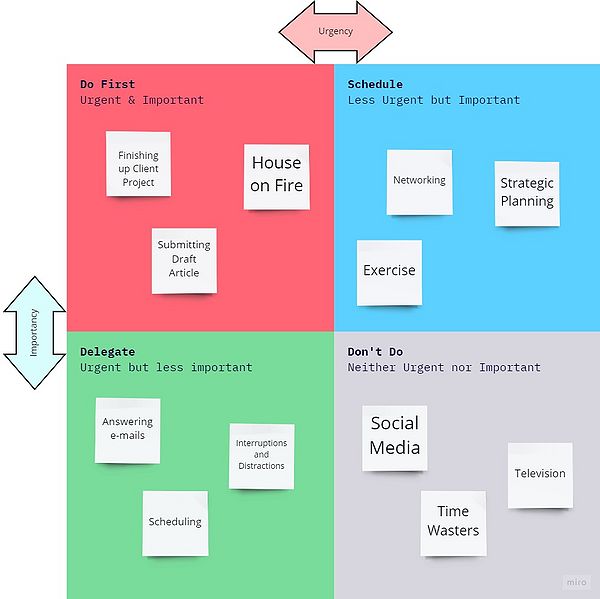

The Eisenhower Matrix is a 2-by-2 cell matrix, where the vertical axis represents Importance, and the horizontal axis represents urgency. The tool is used to prioritize tasks, thus aiding the user to plan short-, mid- and long-term decision through the order of executing the tasks. One of the main aims of using the Eisenhower Matrix, is to create a higher awareness and focus on tasks with a higher payoff, rather than those with a greater urgency. Thereby, this tool is optimal in the negation of the ‘Mere Urgency Effect’!

For Project Managers, this tool can provide assistance when it comes to time-management and prioritization. This can further help organizing and planning project. The Eisenhower Matrix can be of additional benefit, if the means of the prioritization can be communicated out to the project team. Furthermore, the tool can complement other Project Management methods, such as PRINCE2, due to similarities in their principles and aims. The Matrix however, requires for optimal implementation that the manager using the tool, is able to critically reflect on the tasks and project plan.

Mere Urgency Effect

When it comes to human psychology, there are certain cognitive biases that an individual experiences when faced with decision making. One of these biases is the ‘projection bias’, which encourages the undertaking of larger tasks due to a feeling of optimism, even though this feeling is neither perpetual nor long-lasting. Another one of these biases is the ‘restraint bias’, where there is an overestimation of the control that a person has over impulsive behaviors and an underestimation of the effect that distractions causes on productivity[1]. These cognitive biases contribute to the ‘Mere Urgency Effect’. When faced with upcoming objectives, the ‘Mere urgency Effect’ causes a change in perception with regards to the importance and urgency of the task. This shifts an individual’s ability to make decisions towards an emphasis on tasks that appear more urgent, even though they are less important or less fulfilling in regards to the progress of the overall project. [2]

Experiments

To investigate the Mere Urgency Effect, several experiments were conducted in 2018, by Meng Zhu, Yang Yang and Christopher Hsee. The purpose of these experiments was to find out how people chose to prioritize tasks of varying urgency and importance. [1] The first experiment was conducted with 124 college students, where participants were presented with two Tasks that they could choose from, namely Tasks A and B. The aim of both tasks was to write five product reviews within five minutes. However, the students would be randomly placed under two conditions for these task. The ‘Urgency’ condition offered 6 points per review for task A and indicated it expired in 10 minutes, while task B offered 10 points per review, and was set to expire in 24 hours. Furthermore, these students were told that for every 10 points they earned, they would receive a ‘Hershey’s Kiss’ [Chocolate]. The ‘Control’ condition, however, would establish that Tasks A and B only varied in points, but that both expired in 24 hours. Although, all tasks would automatically be finished after 5 minutes. [3]The outcome of the first experiment showed that under the ‘Urgency condition’, students were willing to give up the high payoff tasks, because the low payoff tasks were defined with a non-existent urgency. Under the ‘Control’ condition, this was significantly less prevalent. [3] The subsequent experiments that were conducted included 203 contract workers from Amazon Mechanical Turk. The aim of these experiment’s first part was similar to the previous experiment, in that it included a bonus depending on the chosen task and a given time restriction. The contract workers were given a fixed rate of $0.5 cents per task, with additionally either $0.12 or $0.16 cent bonuses, depending on the tasks. However, these experiments contained additional procedures, such as giving slight hints towards the payoffs of the tasks prior to the workers choosing the tasks, as well as actively informing the workers of the payoff differences, during the time they had to choose the tasks. The experiment concluded that giving attention to higher outcome tasks, through any means, had a mitigating effect on the ‘Mere Urgency Effect’. [3]

Accordingly, tools such as the Eisenhower Matrix can work as reminder to the tasks and problems that seem urgent. By effectively prioritizing the outcome and the time sensitivity of objectives, one can avoid the trap of spending time on urgent but unimportant tasks.

The Four Quadrants

The Eisenhower Matrix consists of four quadrants, with each of them signifying them importance of a given task.

Do First

The first quadrant, in the top left of the matrix, is called the “Do First” quadrant. The tasks assigned to this quadrant are characterized by both their Importance and their Time-sensitivity. These tasks typically have an upcoming deadline, as well as severe consequences if postponed. However, these tasks can also be surprises from an external source, requiring a crisis-level response. In this quadrant it is essential to get the tasks completed in a timely manner, before their urgency becomes more severe. Covey however, suggests that spending too much time in the first quadrant, due to its deadline driven nature, can cause increased stress and burn out. [4]

Schedule

The quadrant in the top right of the matrix is called the “Schedule” quadrant. Similarly, to the ‘Do First’ quadrant, these tasks are significant but are not time sensitive. The tasks in this quadrant are usually focused on growth and development, or ‘deep work’, and usually involve organizing, goal setting, strategic thinking and working on long-term projects. Allocating time in this quadrant benefits skill development and relationship building. Furthermore, by scheduling your tasks efficiently and spending more time in the second quadrant, the smaller number of foreseeable tasks end up in the first quadrant over time. [5]

Delegate

The third quadrant, in the bottom left-hand side, is the ‘Delegate’ quadrant. These tasks are typically those that signify and embody the ‘Mere urgency effect’, because they seem urgent, but don’t carry any importance or significant payoff for completion. If one is to spend too much time in this quadrant, the work becomes less meaningful as the focus is not on the matters that are important to the individual. [5] Identifying the tasks that can be delegated, either to services or co-workers, allows more energy and time to be spent on more important tasks in the upper quadrants. If tasks in this quadrant cannot be delegated, they should be executed after completing tasks in the first two quadrants. [4]

Don't Do

In the final quadrant remain the tasks that are neither urgent nor important. The tasks are often considered a waste of time and unproductive. Spending excessive time in this quadrant can cause too much effort being put into objectives that are considered distractions, and therefore shift the focus away from spending time in the upper two quadrants. Therefore, the time spent in the ‘Don’t Do’ quadrant should be eliminated as much as possible. It is noteworthy, however, that the tasks in this quadrant are not completely useless. Recent studies show certain benefits of having proper leisure time. Some examples are that of individuals engaging in self-mastery activities showing more motivation, while others that spent free-time watching television showed increased positivity when showing up to work the following day. [6]Even President Eisenhower was known for spending time off playing bridge and golf. [5]

Applications and Implementation

A tool such the Eisenhower Matrix can be well utilized within Project and Program Management, while also being applicable in a multitude of fields. Therefore, it is paramount to consider how the tool can be applied, how it can be implemented in the managerial field, along with how it has been applied elsewhere.

With the Eisenhower Matrix being a proposed ‘Self-Management’- tool, there is no explicit way of how to apply the Matrix. Whether it is being used for personal and individual goals or used in the context of planning large-scale projects for business, the Matrix will look different at every instance. Nonetheless, some self-assessment is required when working towards any objective, so as to identify which tasks to prioritize, which in turn will lead to achievement of the goal in mind. Consequently, the precursors to use the Eisenhower Matrix can be established as such:

- Establish Purpose: Regardless of the context in which the Eisenhower Matrix is put to use, an aim or ambition must be defined. By establishing the purpose of a project or personal goal, it becomes clear what the end results should look like, along with what this result should encompass. Moreover, it is likely that the efforts required to achieve the goal will become more apparent. This is something that can be conventionally identified as Covey’s 2nd habit, “Begin with the End in Mind”, which helps give a clear vision or direction of one’s purpose. [4]

- Identifying and Categorizing Tasks: Depending on the set goal, and depending on the context of use, the tasks that follow will always vary. The project manager trying to innovate something in their product range will have a different set of tasks than the university student trying to pass a course in management. While identifying the tasks at hand might be simple, the categorization of them is where the effects of the Eisenhower Matrix appear at first. The tool requires the differentiation between tasks that are urgent and those that are important, which is a distinguishing feature to the Matrix when compared to other tools. [1]Important tasks are constituted by their payoff contributing to long-term targets and objective, while urgent tasks are considered to require immediate attention or have a nearing deadline.

- Quadrants and Prioritizing: Once the tasks are categorized into Important or Urgent, it is easier to delimit them into the Matrix. Naturally, some critical thinking is required to determine which tasks are more Important than others, and which urgencies can be postponed or delegated. Thus, even in the creation of the Matrix, it is important to mitigate the ‘Mere Urgency Effect’, to avoid long-term goals seem urgent, or having less important but urgent tasks being forgotten. This can be done by further prioritizing every task within the quadrants, consequently determining whether the highest or lowest prioritized tasks within a quadrant belong to a different one. Additionally, setting a limit on the number of tasks that can be put under a quadrant, can aid in the process of prioritizing. [7]

- Revision: As Covey suggests with his 3rd habit, ‘Put First Things First’, after the tasks have been set and prioritized within the quadrants, they should be revised. [4]This is important for any use of the Matrix. If certain tasks have been either wrongly prioritized or misplaced into the wrong quadrant, the matrix and general approach should be evaluated and changed to fit the direction of one’s objectives. Optimally, there should be an effort towards staying as much as possible in the second quadrant. The tasks in the second quadrant contribute to the objective in general, or in other words, have a high payoff. The quadrant is optimal for long-term planning and maintaining an overview of the project at hand. Moreover, keeping in line with these tasks eliminates them from being postponed and eventually becoming urgent. As such the first quadrant is kept free for pure emergencies. [8]

- Taking Action: Finally, while not being part of the Eisenhower Matrix, one of the most important factors for successfully executing the use of a decision matrix, is acting. Without acting on the tasks, prioritization and planning become obsolete. Whether this involves the so called “Eat the Frog” or “Pareto” principles to get going, the most important thing is that there is a contribution towards the goal. This is the principal habit of Covey, to be proactive! It states: “You are the creator, you are in Charge” [4]

The Eisenhower Matrix in Project Management

Managerial roles, regardless of respective fields and industries, will to some extent be given the responsibility to understand and handle quantifiable resources within their business. Whether these be financial, logistical, or material resources, they are generally considered core benchmarks that determine status and progress in any project or program. Managers will, however, undoubtably face challenges with intangible assets such as personnel and intellectual resources. The success of project outcomes, and by extension program or portfolio outcomes, can be attributed to how effectively management has handled the people-related aspects.

The PMBOK Guide for Project Management asserts the several performance domains that specify a project’s areas of focus. A considerable proportion of these areas are linked to the leadership that encompasses the project. One of the leadership skills that are outlined as a necessity for project managers is that of self-management, as this involves critical reflection and the avoidance of acting on impulses. [9]The Eisenhower Matrix, inherently being a tool for self-management, commonly fixates on these elements. The use of the matrix by leaders of workgroups assists the individual in time keeping, prioritization, and organizing throughout the project. Conversely, a manager’s self-management can drastically improve the direction of the projects and will accordingly reflect onto the team. [9]

Suppose a project manager is able to consistently prioritize the tasks that span throughout the project. The scope of important and urgent tasks surrounding stakeholders, processes and deliveries can then be planned out accordingly. More importantly, if these plans can be communicated to the project team, it promotes a shared understanding of the direction that management has decided upon, resulting in open communication and transparency, which might help break the biases of the management. As such, the matrix not only supports the acting manager, but the full team. The matrix assists in the project becoming a combined effort to tackle Important tasks, while also encouraging personal growth and autonomy through delegation. While urgent tasks or external dependencies can distract the team from more important matters, dealing with them through a team effort can alleviate this negative effect.

These are all aspects which contribute to high-performing teams within project management, according to the standard for project management. [9]Thus using an Eisenhower Matrix in Project Management and pairing it with other important skills, such as communication, can create a foundation for maintaining vision and focus for the project at hand.

The potential and possibilities of the Eisenhower Matrix are quite clear. Utilizing the tool for time management and prioritization, for further organizing and planning, seems to be an ideal asset that could live up to the standards of Project Management. Besides this, it is possible to draw parallels between the use of the Eisenhower Matrix and other certified methods, such as the ‘Projects in controlled Environments’ or PRINCE2 for short. The PRINCE2 guidelines assert under their theme no. 9 for planning, that it is crucial to identify the activities and dependencies, to expand the picture of needed workload. [10]

tThus there are some similarities between the processes of the PRINCE2 method, compared to the processes of creating a time management process.

What’s more, is that the PRINCE2 method also underlines the need for scheduling, as planning activities or tasks are not enough alone. This is a point that both the matrix, as well as Stephen Covey, promote by emphasizing that one should optimally stay within the second quadrant, namely the ‘Schedule’ quadrant.

One of the prioritization tools that the PRINCE2 method presents is the Moscow prioritization technique. The Moscow technique is also split into 4 categories, namely ‘Must Have’, ‘Should Have’, ‘Could Have’, and ‘Wont Have’, and bears a striking resemblance to the Eisenhower Matrix with the criteria for the categories. [10]It could be argued that the Moscow method is more of an approach towards features or product criteria, instead of tasks that need to be executed. Although, a counter argument could be made that these two go hand in hand.

Nevertheless, opposing the two concepts of the Eisenhower Matrix and the PRINCE2 certification is a false dichotomy. Instead, they should rather be seen as complimenting frameworks for achieving effective and efficient planning and scheduling, when managing projects.

| MoSCoW | Eisenhower Matrix |

|---|---|

| Must Have: Acceptance Criteria or Quality which is essential and critical. Business justification not viable without. |

Do First: Tasks which are categorized as both important and urgent. Objectives must be acted on and are vital to long-term goals |

| Should Have: Acceptance Criteria or Quality that is important but not critical. Absence weakens business justification. |

Schedule: Tasks which are categorized as important but not urgent. Objectives do not have a deadline, but are vital to long-term goals |

| Could Have: Acceptance Criteria or Quality that is useful, but not critical. Absence doesn't weaken business justification. |

Delegate: Tasks which are categorized as urgent but not important. Objectives must be acted on, but don't contribute to long-term goals. |

| Won't Have: Acceptance Criteria or Quality considered, but will not be delivered. No impact on business justification. |

Don't Do: Tasks which are categorized as neither important nor urgent. Objectives must not be acted on, and do not contribute to long-term goals |

Limitations

In common with any framework or tool, the Eisenhower method is no failsafe solution to achieve perfect time-management, nor is the answer to the intricacies that Project Managers may face. As previously mentioned, the Eisenhower Matrix requires certain levels of assessment and critical thinking, being a self-management tool. Thus, depending on the emotional intellect and skill that a project manager possesses, the outcome of the Eisenhower Matrix will vary greatly. One vital aspect of this holds true, when taking into account the full scope of the experiments conducted with regards to the ‘Mere Urgency effect’. Apart from the positive effects of reminding subjects on the payoff of tasks, thereby attenuating the ‘Mere Urgency effect’, part of the experiments identified conditions detrimental to the subjects’ perception of urgency. This part of the experiments demonstrated that people who perceived themselves as busy were more susceptible to the ‘Mere Urgency Effect’. [3]For this reason alone, it can be stated that some of the limitations of using tools such as the Eisenhower Matrix, lie solely within the individual managers’ capabilities of breaking out of own biases and perceptions.

Other limitations to the matrix have been outlined in an article from the ‘Diagrammatic Representation and Inference’ conference in 2020. The article states that the Eisenhower Matrix, and thereby Covey’s reinterpretation, are misleading, as they only provide four types of priorities. It argues the tool misses a crucial aspect, which they dubbed as ‘fit’. The ‘fit’ is essentially a designation of whether the user or manager is needed for the task. As a result, they proposed a variation of the matrix, called the ‘Sung Diagram’ which incorporated ‘fit’. [11]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 The Decision Lab. The Eisenhower Matrix. https://thedecisionlab.com/reference-guide/management/the-eisenhower-matrix. Last Accessed: 2023-05-09

- ↑ Kennedy et. al., 2021. ‘’The Illusion of Urgency’’. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education. Massachusetts, USA

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Zhu et. al. 2018. ‘’The Mere Urgency Effect’’. Journal of Consumer Research. Oxford University Press

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Covey, S.R. 1990. ‘’The 7 habits of highly effective people’’. New York, USA. Free Press

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Todoist. The Eisenhower Matrix https://todoist.com/productivity-methods/eisenhower-matrix#the-mere-urgency-effect-aka-why-were-bad-at-prioritization Last Accessed: 2023-05-09

- ↑ Ouyang et. al. 2019. ‘Enjoy Your Evening, Be Proactive Tomorrow: How Off-Job Experiences Shape Daily Proactivity’’. Journal of Applied Psychology. American Psychological Association

- ↑ Asana. The Eisenhower Matrix: How to prioritize your to-do list, https://asana.com/resources/eisenhower-matrix Last Accessed: 2023-05-09

- ↑ Product Plan. Eisenhower Matrix, https://www.productplan.com/glossary/eisenhower-matrix/ Last Accessed: 2023-05-09

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Project Management Institute, Inc.. 2021. ‘’Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge’’ (PMBOK® Guide) (7th Edition). Project Management Institute, Inc. (PMI).

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Axelos Limited. 2017. ‘’Managing Successful Projects with PRINCE2’’. TSO.

- ↑ Batterud et. al. 2020. ‘’The Sung Diagram: Revitalizing the Eisenhower Matrix’’. Diagrammatic Representation and Inference. Tallinn, Estonia