Group Development - The Tuckman Model

Developed by Céline Engelbrecht Galea-Larsen

Abstract

There are various models on group development. This article is suitable for project managers and group members, who wish to gain insight on Bruce Tuckman’s model on group development - a popular model amongst project managers. This article points out that the Tuckman model originally consisted of four stages through which a group pass on the way to becoming a high-performing group. In fact, Tuckman’s model is also known by the names of the four stages – the ‘forming, storming, norming and performing’ model. However, after revisiting the model, Tuckman, together with Mary Ann Conover Jensen, added the ‘adjourning’ stage. These five stages are described in more detail in the section called ‘The Stages of Group Development’. Consequently, in the section ‘Application – A practical approach’, this article provides a practical scenario on how a project manager can apply Tuckman’s model. This article reminds the reader that the Tuckman model does not necessarily have to be followed according to these predetermined five stages but given it is in principle, a theoretical approach, it should be applied according to the specific needs of the group. The latter recommendation is further justified by describing the shortcomings of the Tuckman model in the ‘Limitations’ section. As the Tuckman model is about five decades old, this article also discusses whether the model is still relevant in the age, where working from home is the new norm, practically shifting project management to a virtual setting.

Contents |

Relevance to the management of projects

Research suggests that “what a group is able to achieve, depends in part on its stage of development”[1](p. 376). One of the most popular models used in project management to guide such group development is Bruce Tuckman's five stages of group development. It is important to note that the Tuckman model initially consisted of four stages. However when the model was revisited, a fifth stage was added. It is advised that project managers approach Tuckman's group development model in a flexible manner, according to the different needs and requirements of the groups at their different stages[1](p. 377).

- The strength of the team is each individual member. The strength of each member is the team.

In a fast-changing and competitive economy, project managers and employees alike must perform at higher and higher levels[1](p. 20). Achieving high performance is critical. However, effective or high-performing teams do not just happen. It requires hard work, collaboration, trust and commitment. In addition, an important ingredient in establishing high-performing groups or teams is effective leadership[1](p. 376). A project manager generally assumes this role in a group, because s/he would have the skill-set to motivate, direct and lead the group to achieve the project’s outcomes[2](p. 56). Additionally, the project managers strive to find ways to help groups function more effectively with awareness and compassion for each other to ultimately improve the group’s performance[1](p. 377).

The Stages of Group Development

The Tuckman model

In his article, ‘Developmental Sequence in Small Groups’ from 1965, Bruce Tuckman introduced the phrase ‘forming, storming, norming and performing’ to describe how groups are developed [3]. These four stages of group development were based on Tuckman’s literature review[3]. Tuckman, analysed 50 articles where group development was the main focus. The articles examined included three types of groups: Groups therapy, training groups, and laboratory groups [3]. In his research, Tuckman explains how as the group progresses through the four stages, it changes from being a collection of random individuals to a high performing group - i.e. a group that effectively works together to fulfil its full potential[4]. The four stages presented by Tuckman are illustrated in Figure 1.

- Forming

- At this first stage, group members start to get acquainted with one another and try to get an understanding of the group’s intended purpose and what they would be expected to do to reach the group’s common goals[1] (p. 376). Because of the level of uncertainty, the forming stage is also “characterized by the emergence of leadership”[3], where group members rely on the project manager “to define the directions the group will pursue” [3].

- Storming

- The storming stage is an important stage to pass through. “The lack of unity is an outstanding feature”[3] and it can make or break the group’s development. As the members start to feel confident in expressing themselves within the group, an inter group conflict starts to emerge due to the different personalities and working styles[5]. The project manager must ensure that the conflict does not get out of hand [1](p. 376). Group members must use their varying opinions to the group’s advantage to achieve the group’s tasks and goals[4].

- Norming

- In the norming stage, the group becomes “a cohesive unit and develop[s] a sense of being as a group”[3]. In fact, Tuckman further stated that “task conflicts are avoided to insure harmony” in the group[3]. In other words, the group is able to resolve their differences, appreciate each other’s strengths and share a stronger determination to achieve the group’s goals[4].

- Performing

- In the performing stage, the group develops “a positive interdependence”[3] and a sense of autonomy. This means that if a problem arises, the group members do not specifically have to be instructed by the project manager on what to do but they are able to adapt in the roles and take the appropriate decisions themselves in order to overcome the problem constructively. Hence, there are more functional roles within the group[5] and “group energy is channeled into the task” at hand[3].

Adding of a fifth stage

In 1977, Tuckman and Mary Ann Conover Jensen, who at that time was a PhD student with a background in counselling psychology, carried out a follow-up study - “Stages of small-group development revisited”[6] - in order to find out if anyone had empirically tested the model, modified the model or invented a new model regarding group development in the years since the article came out it 1965[6]. The investigation ended up identifying a fifth stage - adjourning.

- Adjourning

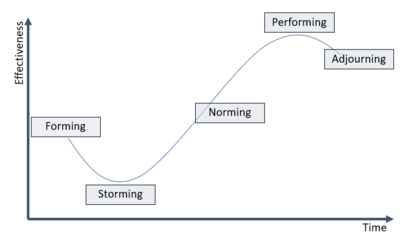

- The adjourning stage is based on the approach that the development follows a life cycle model view[6], where the group’s goals have been accomplished and the focus is on completing the final tasks and documenting the efforts and results. In other words, this is the break-up of the group, where group members are reassigned[4]. The group development progress and the level of effectiveness of the group within each stage is visualised in Figure 2.

Application - A practical approach

Even though the Tuckman model was developed 56 years ago, it is well-known and widely used today. However, it is important to note that the Tuckman model is a theoretical approach, not a strict tool to implement by project managers. It is considered to be a helpful source to understand not only the possible stages within different groups but it supports the project managers to take practical steps in developing a high-performing group at these identified stages[7]. This means that the Tuckman model does not have to necessarily be strictly applied but can be applied loosely according to the specific need of the group.

In order to depict how the Tuckman model can be applied by a project manager, let us take a scenario where Tom has been asked to lead a major project (adapted from [8]). He has been assigned five individuals within his department to help him. Tom has a tight deadline to complete the project. Therefore, he must try to be an effective project manager so that together, they would be able to effectively complete the project in time. Tom is familiar with Tuckman’s model of group development. In every stage, we will see how Tom is able to manage the group.

- Forming

- Tom is aware that this initial stage is represented by “a period of orientation and information”[3]. Consequently, he calls for a kick-off meeting for the project. Before the meeting, Tom ensures that he is well-prepared to answer any questions that the other group members might ask, for example, regarding their roles and the goals they need to achieve. Tom decides to start the meeting by having a tour de table, where every group member (including himself) was able to introduce themselves. After the ice-breaking session, Tom provides information about the project they have been assigned, keeping it as simple as possible and focusing on the objectives they have both as a team and as individuals. As the meeting continues, Tom can see that the group members are more at ease and trusting of his leadership.

- Having ticked all the right boxes in this initial stage, the group is able to move onto the storming stage.

- Storming

- Tom knows that the storming stage is a crucial phase of group development to manage. Although he is content to see that the group members are more vocal about their opinions and ideas during the meetings, Tom begins to notice that disagreements and disputes begin to break out in the group. Anne and Peter have had previous experience in project management, and Peter can see that they are trying to establish themselves in the group and undermine his leadership. Additionally, he also sees that Sophie is not as engaged. Sophie has recently joined the company so Tom thinks that she is feeling insecure to share her opinions with the rest of the team, who seem to be more experienced than her.

- Tom remains positive. He decides to create a governance process to ensure that unresolved disputes are not left unchecked but dealt in a professional and non-judgemental way. Tom also reminds the group’s objectives and responsibilities, and establishes short-term milestones to focus their attention on the tasks at hand. At this crucial stage, he also organises meetings with the individual members of the group so that they can share any concerns and opinions[9].

- By exerting his influence and providing direction, Tom reasserts his leadership and the group is brought back on track.

- Norming

- The group is working well and is fully committed to achieving the project’s goals. Tom can see that the group is not solely dependent on him. He continues to encourage the members of the group to support each other, to ask feedback from one another and to share their knowledge with each other.

- Performing

- The group has been performing very well and in fact, Tom is also able to step back and focus on other projects and tasks, whilst he delegates the remaining tasks respectively among the group’s members. The group has become high-performing and autonomous and does not require full supervision of the group’s tasks. During a social gathering, Tom thanks all the group members and expressed that the project’s achievements would not have been possible without them. As the most experienced members of the team, Peter and Anne expressed to Tom that they really enjoyed working on the project and it was the most fun they have had in a while on a project.

- The project is set to finish on schedule.

- Adjourning

- The project has been completed on time and all the relevant documentation has been filed. Tom’s boss is very happy with the results. Feeling positive about what the group has achieved, Tom invites the group members to a celebratory dinner to recognize the group’s achievements. Tom and the group members have already been assigned to other projects in the company but they do hope that they get to work together again.

Limitations

Even though the Tuckman group development model is still the most popular model describing group development theory, it is not without its critics.

The first significant limitation of the model is that it “cannot be considered truly representative of small-group development processes”[3]. In fact, the therapy-group setting was the most dominant amongst the group-settings that Tuckman analysed[3]. Cassidy (2007) conducted a study to find out whether Tuckman’s description of group development is applicable to other contexts outside of the therapy-group setting[10]. Cassidy’s findings indicated that although Tuckman’s five stages of group development were able to be applied in the sample of group models she studies, the difference was that conflict did not only appear in the storming stage. In this regard, she considers that the focus should not be to look at conflict as a stage but rather to explore the concerns that drive the conflict[10]. This shift in focus would “integrate the seemingly diverse models found in practitioner literature”[10].

The Tuckman model was also criticised as being idealised and lacking face validity[11]. Rickards and Moger’s empirical observations reveal that specific teams are more complex than in Tuckman’s simplified model[12]. In fact, another limitation considered by several authors is that the Tuckman model assumes that the groups progress linearly (Agazarian & Gantt, 2003; Connors & Caple, 2005; Miller, 2003; Tubbs, 2004)[13]. Furthermore, Rickards and Moger ask two questions, which the Tuckman model failed to address: “what mechanisms are at play when a team fails to achieve expected performance?” and “what mechanisms lead to outstanding performance?”[11]. In other words, under Tuckman’s model, a group can never effectively achieve their goals, if it is unable to progress from the norming to the performing stage.

Researchers, such as Gersick (1989)[14], have also called the Tuckman model into question in its inability to “address mechanisms for change over a group’s lifespan”[5], including the time it would take for a group to move from one stage to the next[13]. Additionally, Tubbs (2004) suggests that the Tuckman model should be more circular in nature to allow the group to learn from their mistakes and improve as a whole[13].

Is the model still relevant?

In the age of ‘social distance’, organisations across every sector have shifted their operations to an online setting. Managers have unexpectedly (and in certain cases, without preparation) have had to lead their teams virtually for the first time. The question then arises as to whether the Tuckman and Jensen model (1977)[6] is still applicable to the development of an online group.

Whilst Tuckman’s five stages of team development is generally applied to form new groups, it can also be applied to already formed groups that experience change[15]. What may be different today is whereas in the past, we would have waited on our manager to tell us how to get our job done, we tend to work according to the agile movement approach, where once we understand the objective, we tend to self-organise around tasks without the need of waiting on the manager[15].

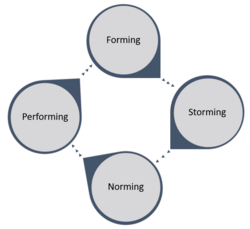

As indicated in the limitations section, the Tuckman model is a linear one. When we work remotely, we may encounter challenges: technological issues (e.g. choosing the appropriate platform or tool to have online meetings with your team); building relationships at a slower pace due to a lack of face-to-face communication; learning curve to adapt to the new ways of working and/or to use the online platforms. In this regard, the Tuckman model could be further adapted to be more cyclical[15]. Most often than not, the group needs to adapt their way of working and collaborating with each other (e.g. a new person joins the group or the group receives another strategic direction to consider in their project). Therefore, even when these unexpected circumstances may push back the group down a stage or prolong the group in a particular stage[16], it does not mean they fail but rather that the group would have to adapt to get back on track to becoming a high-performance group. A representation of the more circular approach to the Tuckman model can be seen in Figure 3. The adjourning model has been excluded from the figure, given the fact that at this stage, the objectives would have been achieved.

Patience, persistence, communication and presence are required to lead virtual teams. To complement these leadership traits, models like the Tuckman group development model can be adapted to allow managers and leaders to build upon existing skills to create a highly successful virtual team[16].

The application of the Tuckman model has not only shown the importance of leadership in a group setting, but also the importance of delegation when the group is working well and high-performing (at the norming and performing stages). This is also what makes management more effective, that is leaders that are not just focused on how well they perform, but in developing a group of people (a team) that successfully delivers results[8]).

Annotated bibliography

The following list provides additional resources for further reading on the Tuckman Model and group development:

- Adams, S. L., & Anantatmula, V. (2010). Social and behavioral influences on team process. Project Management Journal, 41(4), 89-98.

- - This article was published in the Project Management Journal. It presents a self developed model in order to describe the individual group members' influence on their group development. The self-developed model is based on various models of group development, the principle one being the Tuckman model. Furthermore, it provides useful recommendations to manage the group at each of its presented stages, which could also be useful to implement by project managers.

- Rickards, T., & Moger, S. (2000). Creative leadership processes in project team development: an alternative to Tuckman's stage model. British journal of Management, 11(4), 273-283.

- - This article brings another element to group development, that is creative leadership. The authors do base their research on the Tuckman model, in that they acknowledge the five stages of group development. However, they propose that some of the stages should be merged and more focus should be put on "breaking the barriers" between each stage, rather than jumping from one stage to another. They also argue that there is an additional stage after the "performance" stage, which they call the "outperforming" stage. In addition, they argue that a project team performance can only be enhanced by creative leadership. To this effect, they propose seven factors that is affected by creative leadership, which in turn helps a group reach the "outperforming" stage.

- Williams, J. (2002). Team development for high-tech project managers. Artech house.

- - This book focuses around team dynamics and project management. It provides the reader with the fundamentals of theory and practical guidelines to build a successful performing team. In this regard, the reader can expect to gain knowledge on, inter alia, team development, how to motivate teams, conflict resolutions and empowering others.

- Blaskovich, J. L. (2008). Exploring the effect of distance: An experimental investigation of virtual collaboration, social loafing, and group decisions. Journal of Information Systems, 22(1), 27-46.

- - This article takes a quantitative experimental approach in order to analyze the difference between face-to-face groups and virtual groups, with regards to individual effort and group performance. One of their conclusions was that virtual groups were more disposed to loafing behavior. Furthermore, they suggest ways of optimizing virtual group performance.

Reference

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Jones, G. R., & George, J. M. (2017). ‘’Essentials of contemporary management.’’ New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education.

- ↑ Project Management Institute, Inc.. (2017). Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide) (6th Edition). Project Management Institute, Inc. (PMI). Retrieved from https://app.knovel.com/hotlink/toc/id:kpGPMBKP02/guide-project-management/guide-project-management.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 Tuckman, B. W. (1965). Developmental sequence in small groups.Psychological Bulletin, 63(6), 384-399. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0022100

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Bruton, J., & Bruton, L. (n.d.). ‘’Five Stages of Team Development - Principles of Management’’. Lumen learning. Licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/. Retrieved 17 February 2021, from https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-principlesmanagement/chapter/reading-the-five-stages-of-team-development/.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Bonebright, D. A. (2010). 40 years of storming: a historical review of Tuckman's model of small group development.’’Human Resource Development International’’, 13(1), 111-120. https://doi.org/10.1080/13678861003589099

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Tuckman, B. W., & Jensen, M. A. C. (1977). Stages of Small-Group Development Revisited. ‘’Group & Organization Studies’’, 2(4)', 419–427. https://doi.org/10.1177/105960117700200404

- ↑ Clarity leadership. (n.d.). ‘’The Tuckman Model of Team Formation’’. Clarity leadership. Retrieved 17 February 2021, from https://www.clarityleadership.co.uk/blog/tuckman-model-team-formation.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Heflin, J. (n.d.). ‘’Putting It Together: Groups, Teams, and Teamwork’. Lumen learning. Licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/. Retrieved 17 February 2021, from https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-principlesmanagement/chapter/putting-it-together-groups-teams-and-teamwork/.

- ↑ Priestley, D. (2015). ‘’Forming, Storming, Norming and Performing: The Stages of Team Formation’’. Venture Team Building. Retrieved 20 February 2021, from https://ventureteambuilding.co.uk/forming-storming-norming-performing/#.YDFWE3ko9EZ.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Cassidy, K. (2007). Tuckman revisited: Proposing a new model of group development for practitioners. ‘’Journal of Experiential Education’’, 29(3)', 413–417. https://doi.org/10.1177/105960117700200404

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Rickards, T., & Moger, S. (2000). Creative leadership processes in project team development: an alternative to Tuckman's stage model. ‘’British journal of Management’’, 11(4)', 273–283

- ↑ Berlin, J. M., Carlström, E. D., & Sandberg, H. S. (2012). Models of teamwork: ideal or not? A critical study of theoretical team models. ‘’Team Performance Management: An International Journal’’, 18(5/6)', 328-340. https://doi.org/10.1108/13527591211251096

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Hurt, A. C., & Trombley, S. M. (2007). The Punctuated-Tuckman: Towards a New Group Development Model. ’’Online Submission’’

- ↑ Gersick, C. J. (1988). Time and transition in work teams: Toward a new model of group development. ‘’Academy of Management journal’’, 31(1), 9-41.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 Sedmak, J. (2020). ‘’Stages of Team Development During Times of Change’’. SME Strategy Management Consulting. Retrieved 20 February 2021, from https://www.smestrategy.net/blog/stages-of-team-development-during-times-of-change.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Hayes, k. (2017). ‘’Adapting Tuckman’s Model for Global Virtual Teams’’’. Insync Training. Retrieved 20 February 2021, from https://www.smestrategy.net/blog/stages-of-team-development-during-times-of-change.