Hersey and Blanchard's Situational Leadership

The general way of leading people can vary greatly between countries, cultures and industries, and has changed significantly over the last decades. The classic way of leading people was with a centralized decision-making in a top-to-bottom-approach, where management settled upon a direction, in which the people on the floor was commanded to follow. Today the general model of leading has been turned upside down, and now has the bottom-to-top approach, where employees can make decisions themselves, and are now recognized for their competences [1].

As a project manager, one of the key roles when facilitating a project, is to lead a given project team in the desired direction. This is done by utilizing and improving each team members core competences, whilst developing and supporting their weaker points, but this can be quite a challenge. Leadership is an art form, and there are about as many ways of leading people, as there are leaders. One way of doing it, is through an adaptive leadership style, where the style of leadership is dependent on the given situation at the given time. This form of leadership is called 'Situational Leadership' (SL), and proposes four different leadership styles, that each are appropriate at different stages of the team’s development:

- Directing

- Coaching

- Supporting

- Delegating

The stage of development in the team is very dynamic and will change over time. The style of leadership must therefore be adaptive to accommodate these changes [2].

Throughout this article, the history of the SL-framework, the framework itself, and its area of application will be explained in relation to the topic of project management. The statements will be substantiated with relevant examples, and there will furthermore be accounted for the limitations of the SL-framework.

Contents |

About Situational Leadership

When being in charge of a project as a project leader, the work is balanced out onto three main skillsets: 'Technical Project Management', 'Strategic and Business Management' and 'Leadership', as stated in the PMI Talent Triangle [3]. This article focuses on the leading-aspect of being a project leader, and this is done by both managing and leading a project team. The difference between these two words lies in their definitions, which respectively is by "Having executive control or authority"[4] over someone, and to "Show (someone or something) the way to a destination by going in front of or beside them"[5]. Thus, leading and managing are vastly different approaches to running a project, and how these two factors are balanced, defines the style of leadership that is applied. Which style to apply will be dependent on the situation you find yourself in at that moment of time, and will therefore change. You will therefore constantly need to adapt to these changes, and a way of deciding upon the most fitting style, will be determined using SL to assess both the given situation, but also the maturity of the project team members.

The framework of SL was founded in the 1960'es by two American psychologists named Paul Hersey and Kenneth Blanchard. They came up with the theory of SL, which at first was named the "Life cycle theory of leadership" while working on their book called “Management of Organizational Behavior”. This framework is up to this day applied globally with great success among its users, and builds upon common sense, and a belief that leadership is the opposite of one-style-fits-all.

On average, the general project has grown, and the same goes for the project teams, which raises the bar for the capabilities of the project leader, and creates a demand for communicating and leading many team members with different functions and from different departments. This problematic is well described by the following sentence: "When researcher talks to researcher, there is 100 percent understanding. When researcher talks to manufacturing, there is 50 percent understanding. When researcher talks to sales, there is zero percent understanding. But the project manager talks to all of them.” [6]. A project leader applying the situational leadership should therefore adapt to the given circumstances in a team, and manage, lead, guide and support the team members to achieve success in a project [7]. This will be elaborated in the following section.

Applications

To turn the theory of the SL into practice, one of the most important tools for the project leader is common sense. The reason for the framework to be a globally accepted way of leading people, is due to its simplicity and straight-forward approach to the subject. This framework is applicable when managing projects regardless of the scope, or the line of business, if there are project members to lead.

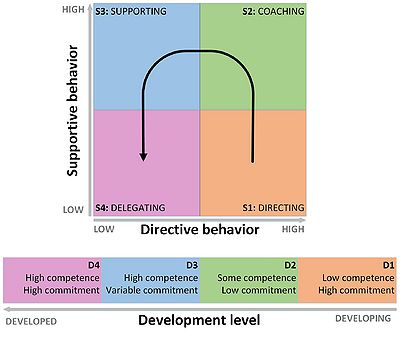

The two dimensions that the project leader is working with in regard to leading the project team members, is illustrated in the figure to the right, and requires an assessment of both the given situation of which the project is carried out in, and the team maturity of which is given by the members.

The style of leadership is shown at the top of the figure to the right, and illustrates a 2x2 matrix giving an overview of the four different leadership styles. These leadership styles are as follows [8]:

- S1: Directing (originally 'telling'): This style of leadership is in the spirit of classic management, where the project leader decides on how the different tasks involved in a project should be carried out by the project team members. Here the decision-making authority is very centralized, which is why no input from the additional project team members is allowed, and the project tasks is therefore decided upon solely by the project leader. The leadership style is therefore high on directive behavior, but low on supportive behavior.

- S2: Coaching (originally 'selling'): This style of leadership is like the S1-style, but also invites the additional project members to participate in the decision-making process. This is typically being carried out in a project meeting where the project leader has set up a work agenda that is discussed, and helps utilize the different competences available among the project members. The leadership style is therefore high on directive, but low on supportive behavior. The leadership style is therefore high on both directive and supportive behavior.

- S3: Supporting (originally 'participating'): In this style of leadership, the decision-making authority is more decentralized, thus requiring a higher level of mutual trust between the leader and the members. Here the project members are making decisions upon the work tasks themselves under supervision from the project leader, and leaves much of the project planning responsibility up to the whole team, rather than the project leader alone. The leadership style is therefore low on directive behavior, but high on supportive behavior.

- S4: Delegating (originally 'telling'): In this style of leadership, the decision-making authority is completely decentralized by delegating the responsibility of directing their own work to the team members. This minimizes the involvement of the project leader, thus setting higher demands for the competences of the project members. The leadership style is therefore low on both directive and supportive behavior.

As is appears from the above-mentioned bullet points, both the S1 and S2 styles has a more result-oriented approach focusing on getting the job done, whereas S3 and S4 are leaning more towards personal development, and working independently. Furthermore, the further you move from S1 towards S4, the requirements for personal competences among the project members are higher, and it is therefore essential to pair the right style of leadership with the development of the team.

The team development (originally maturity) is a more intangible factor to grasp, and has several dimensions to it. In order to make the correct assumptions in regard to the development of the project team, an acquaintance of each member is required to a certain degree. The team development can be both an assessment on which competences the team possess, but even more the familiarity with the work tasks they need to undertake. Is this a team composed of newly qualified employees with little to no knowledge of the given tasks, or are these experienced members that may even have tried the whole ordeal before? Similar to the styles of leadership, the development of the team is broken down into four levels [10]:

- D1: In this level of development, the members of the project members lack both the experience, abilities or the confidence to take on the given tasks themselves. As mentioned before, this could typically be newly qualified employees, or inexperienced members of the project team. The members here will typically have a low level of competence, but a high level of commitment to the project.

- D2: In this level of development, the members of the project possess the experience and abilities to some extent, but lacks the confidence to take on the given tasks themselves. This could be the case with a project team composed of members with more field experience, but who may never have been involved in a similar project before. The members here will typically some of the competences required, but a low level of commitment to the project, due to lack in confidence.

- D3: Here, the project members possess the required competences in the sense of experience and abilities, and will be able to do the required tasks, but the commitment to the project is varying, and the need for support and encouragement from the project leader will continued be required to some extent.

- D4: Here the project members are completely qualified to the given tasks involved in the project, and has the drive themselves to see them through, and to make decisions on their own. The required project leader involvement will therefore be minimal, and is only present to set general project boundaries, and objectives, thus creating the setting for the execution of the project.

As shown in the SL-figure, these levels of team development determine which style of leadership should be applied to a given situation, thus making the form of leadership adaptive. It is important to keep in mind the assessments of the team development should be a constant iterative process, and is highly dependent on the given tasks that is bound to be undertaken by the team members, and the team leader should be ready to backtrack in the case of assessing the team development-wise either too high or low. At the same time, it is possible to have a composition of team members that are non-homogeneous in the sense of capabilities and needs in relation to a given task. The team leader might therefore need to use e.g. S1 on one half of the project team, and S3 on the other half [11].

Limitations

The SL-framework puts the matter of leadership simply enough for most people to understand, and its application and method of using it is very well described. Though, one thing to bear in mind is that it all builds upon the assumption that you have a project leader that meets the requisites of being able to apply the framework in practice. What these requisites are can be hard to determine, since the required attributes in relation to qualities and personality traits are not described in the SL-framework itself. The project leader should have the attributes of being empowering, supporting and motivating as a leader towards the team members, but also learning and educating. Without these attributes, the style of leadership will be stuck in the S1-level, and applying the SL-framework will simply not be possible to carry out with the given project leader. Other important attributes with regards to making the project team-development assessment is to be communicative, and to have some skill and knowledge towards the area that the project is unfolding. Without these abilities, assessing the project team members is simply not possible, and it would not be possible to known if the members are confident or skilled enough to undertake the tasks described in the project plan [12].

Another important aspect to consider is to assess the boundaries of the project that is being carried out. Depending on the time available, given regulations in specific industries, or the financial situation of the project facilitators, all styles of leadership may not be applicable. Typically, the leadership style of S4 is what most project leaders strive towards, because of the autonomy among the project members are distributing out the workload and responsibility of the project. Though, this is only achievable when being resourceful in both time and financially. If times are more critical, deadlines are approaching, and the budget are being challenged, a more centralized way of leading the project may be preferred, thus leaning more towards the leadership style of S1.

No framework is perfect, and there are many ways of leading a project. If the method being used is taken with a grain of salt, and common sense is applied, most frameworks can be used with great success. The framework of SL being a globally accepted way of leading a project is no coincidence, and assuming that the project leader possesses the required attributes, and that the given project allows it, should utilizing SL definitely be considered.

Annotated bibliography

Project Management Institute (PMI) is a globally accepted encyclopedia for project management standards. Here, many articles and information related to Situational Leadership can be found among many other relevant articles.

Essentials of Project and Systems Engineering Management, 3rd Edition (2008) by Howard Eisner provides a great insight to what it means to be a project leader, and to applying situational leadership in practice.

The Human Touch: Personal Skills for Professional Success 2012 by James Cadle, Philippa Thomas, Debra Paul elaborated, and makes great points in general leadership competences for project leaders, and provides a good understanding of situational leadership as a framework.

Refrences

- ↑ Project Management: A guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK guide) 6th Edition (2017) by the Project Management Institute (PMI)

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pykuvuA-QFU seen on 2019.02.19 uploaded by EPM

- ↑ https://www.pmi.org/learning/training-development/talent-triangle visited 2019.02.19

- ↑ https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/managing seen on 2019.02.19 by Oxford Dictionaries

- ↑ https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/lead seen on 2019.02.19 by Oxford Dictionaries

- ↑ 'Project Management - Best Practices - Achieving Global Excellence (3rd Edition) (2006) by Harold Kerzner

- ↑ 'http://blanchard.dk/situationsbestemt-ledelse-II seen on 2019.02.19

- ↑ 'The Human Touch: Personal Skills for Professional Success (2012) by James Cadle, Philippa Thomas, Debra Paul page 70-71

- ↑ 'https://expertprogrammanagement.com/2018/11/situational-leadership-model/ seen on 2019.02.19

- ↑ 'The Human Touch: Personal Skills for Professional Success 2012 by James Cadle, Philippa Thomas, Debra Paul page 70-71

- ↑ 'Essentials of Project and Systems Engineering Management, 3rd Edition (2008) by Howard Eisner page 153-154

- ↑ 'Essentials of Project and Systems Engineering Management, 3rd Edition (2008) by Howard Eisner page 154-156