Ishikawa Diagram

By Tobias Stabrand

This article will describe the Ishikawa Diagram and provide guidance on the tool's application in project management and its usefulness within the fields of risk- and quality management in projects. The article is part of the course 42433 Advanced Engineering Project, Program, and Portfolio Management F2022 at the Technical University of Denmark (DTU).

Contents |

Abstract

Managing projects can be difficult, and projects will oftentimes run into problems no matter how well-planned they are. It is therefore of great importance to monitor projects throughout their lifetime, to identify risks and quality issues, as they can have a significant influence on the desired objective of the project. The Ishikawa Diagram is a tool that can help in identifying and analysing why a problem occurred, what happened, how it can be fixed as well as how to prevent it from happening again.[1] The tool can both be applied in the pre-project activities to identify potential risks associated with a new project, during the project process, and in the post-project activities for evaluation and improvements of future projects.[2]

The Ishikawa Diagram provides a structured approach to finding root causes to given problem´s and breaking down the contributing factors systematically into smaller elements. The systematic breakdown of the problem can make the greatest causes and effects more evident, and thus allow for an effective problem-solving process. The intention is to solve problems at their root rather than at a more superficial level, to prevent the problems from reoccurring.

The purpose of this article is to present the Ishikawa Diagram and its historical context and give hands-on guidance on how to apply the tool to manage risk- and quality problems in projects. Moreover, the article will discuss and explore the application of the Ishikawa Diagram in conjunction with other project management tools. Lastly, the article will present possible limitations of the tool.

The Big Idea: The Ishikawa Diagram

Professor Kaoru Ishikawa was an organisational theorist and was employed at the engineering faculty of the University of Tokyo. He was an expert in quality management and highly respected for his innovations, which includes the Ishikawa Diagram. Due to the diagram’s visual appearance, the tool is also known as the fishbone diagram, but it is also referred to as the cause-and-effect diagram. The methodology was introduced in the 1940s but first popularised in the 1960s.[3] Kaoru Ishikawa pioneered quality management processes at the Kawasaki shipyards, where he was employed and is today seen as one of the founding fathers of modern management.[4] Kaoru Ishikawa invented the tool for managing product quality issues and root cause investigation in the manufacturing industry. However, today the tool is applied to various problems and situations in several industries.

Project management is about coordinating activities to direct and control the project to achieve desired and agreed objectives.[2] Controlling projects are about comparing actual performance to planned performance as well as analysing these differences to be able to take proper corrective and preventive actions. A project should be completed, and objectives are reached within an identified number of constraints, such as: Budget, duration, risk level, governmental requirements, and quality standards.[2]

The Ishikawa Diagram can be used to identify risks and find the potential root causes of an expected problem in risk management.[5] Risk management revolves around increasing the possibility of achieving the project’s objective. This is a responsibility that all project members have and involves identifying, assessing, treating, controlling, and responding to risks.[2] If a risk is experienced or identified at any time during a projects’ life cycle it must be recorded. Thus, it can be assessed for probability and consequence and prioritised for further action.

Quality management in project management is also essential. Quality management focuses on increasing the likelihood that the outputs are aligned with the performance levels that are required to be met.[2] Quality in projects is important to ensure the project’s deliverables and hence quality control activities can focus on the corrective, detective, and preventive actions. For this purpose, the Ishikawa Diagram is good at tracking, identifying, and diagnosing why quality issues occur during project execution and finding effective root causes.[1] Furthermore, the tool is useful to take preventive actions.

The Ishikawa Diagram uses visual representation of the problem which makes it easier to absorb and understand data, and turn it into valuable information. The visualisation eases the identification and helps trace the undesirable effect back to its root cause.[5] Since the Ishikawa Diagram combines brainstorming and visualisation of the causes, it makes the tool very good at both identifying risks and ensuring quality in projects.

Application of The Ishikawa Diagram

The Project Team

To make use of the tool it is necessary and important to gather a team of relevant people since the value of the results are dependent on the team’s ability to identify the causes of the problem of concern. Relevant people are people with an in-depth understanding of the problem, great experience, people closest to where the problem is detected or expected to occur, and people with familiarity with similar problems.[6] The Ishikawa Diagram facilitates a process where the team members are encouraged to communicate and discuss the problem and the possibility of the various causes. Thus, this sets requirements for the project team that are put together as well as make demands for active participation by the team members. The team members should therefore be selected according to their ability to discuss and review the problem.[7]

It can, however, be difficult to choose the right team and the correct amount of people to be part of it. If a too small and less diverse team is gathered it will likely be easier for the group to find common ground, but it might result in an insufficient and non-in-depth Ishikawa Diagram where all causes and perspectives have not been assessed. Hence, the result and plan of action to prevent or solve the problem may be inadequate and the issue might show during the project anyway.

Putting together a bigger and more diverse team can on the contrary shed light on and identify many more possible causes of the problem, which can be an advantage. However, obtaining common ground is crucial and this can be more difficult if the diverse group of people have a focus on their area of interest and the related causes. Thus, it can be difficult for the team to prioritise which of the causes are most likely and most unlikely to occur. This can lead to some causes being overrated while other causes being underrated, due to the diverse nature of the project team. Eventually, the problem might occur during the project anyway because the prioritisation of the causes was done incorrectly, and the plan of action can fall short.

It is recommended to point out a facilitator, who can help narrow down the scope and provide guidance during the process. It should be the project manager and the facilitator that points out the relevant participants. However, it is recommended to hold the participation of management individuals at a minimum, as their presence may inhibit the other team members from speaking up.[7] Active participation, information sharing, communication, and discussion of the problem in-depth are paramount to the result obtained using the tool. Thus, it is a fine balance that the facilitator and the project manager must manage, when putting together the team.

The Procedure

1. Identify the Problem

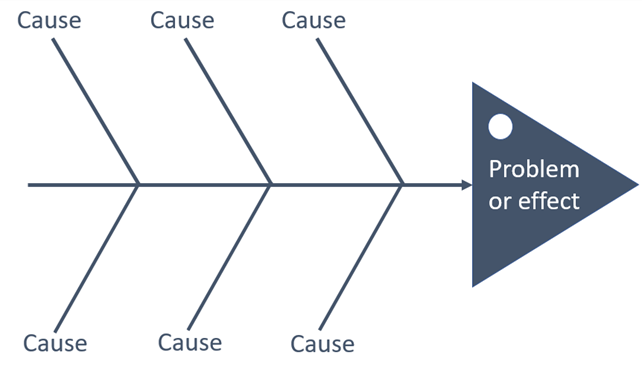

After having gathered the right project team to conduct the Ishikawa Diagram, as described in the previous section, the “head” of the diagram is drawn to the right side e.g., on a whiteboard, addressing the problem or effect that needs to be solved. The problem is written precise and concise to ensure common ground among the team members. Therefore, the problem must, first, be critically discussed to define it correctly to obtain common ground among the participants. Some draw an arrow rather than just a line pointing at the problem to imply that the causes that are to be found are the reasons for the problem, but it has no functional importance.[6]

2. Identify the Major Factors

Next, the team identifies 4-8 main causes to which they can group the sub-causes. The team can either come up with some main causes, that they find relevant to the problem if it is very specific, or they can make use of the 5 M’s, 4 S’s, or 8 P’s, depending on the type of problem. The 5 M’s, 4 S’s, or 8 P’s will be described in more detail later in the article. To allow sufficient space for each main cause and the related sub-causes the “bones” of the diagram should be placed at good distance, to ensure the space is not a limiting factor when performing the analysis.

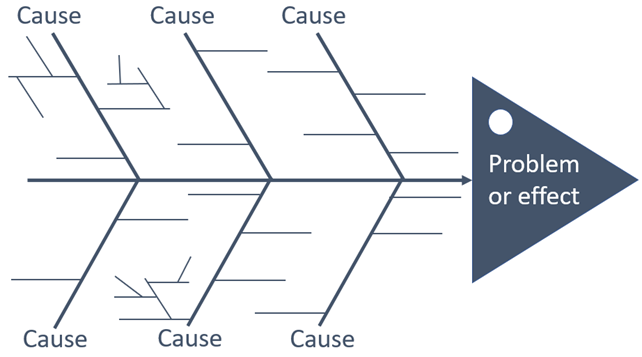

3. Identify Possible Causes

Now the brainstorming process can start. Each “bone” and its corresponding main cause is examined and every sub-cause that the project team can think of will be added as a sub-branch to the diagram. The facilitator can write the things that the team member shout out or the use of sticky notes can be utilised. Using sticky notes can enable more introverted people to participate actively as not all might find it comfortable to speak out loud.

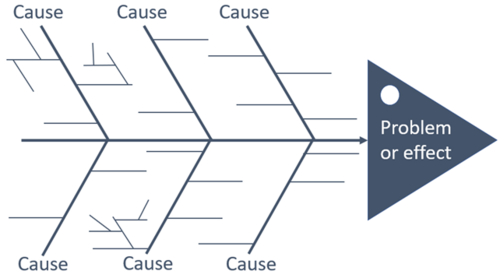

As the branches and sub-branches are being filled in the Ishikawa diagram, the team can start to explore the branches and sub-branches further using the five whys technique. The five whys are used to analyse more levels down, by asking “why” a problem happened up to five times until the root cause has been reached. The technique allows for solving the problems at the root rather than at an immediate more obvious level. It is, however, important to know when to stop asking “why” and not exaggerate the use of it, as it can be counterproductive to the process. [8][1]

4. Analyse the Ishikawa Diagram

After having analysed the problem using the Ishikawa Diagram and potentially the five whys, the team should have been able to reach one or more root causes of the problem. Next, the team must evaluate, assess, and prioritise the causes found according to the causes expected impact. This can be done by asking two questions for each found cause, namely how likely is this cause to be the major source of the problem and how easily can it be fixed or controlled. A scale for evaluating each of the two questions is made up. The scale for the first question could be “Very likely”, “Somewhat likely”, and “Not likely”. While the scale for the second question could be “Very easy”, “Somewhat easy”, and “Not easy”. Rating each of the questions according to these scales, the project team should focus on the combinations “Very likely” and “Very easy”, “Very likely” and “Somewhat easy”, and “Very easy” and “Somewhat likely”. Hereby, the project team can more easily manage their resources and time and pick out and work on those causes with the highest probability.[6]

The Major Factors: 5 M’s, 4 S’s, and 8 P’s

As mentioned previously in the article the project team can either specify the main causes or make use of the 5 M’s, 4 S’s, or 8 P’s, depending on the problem of concern. The project team can naturally add or remove main causes to adjust it to the purpose, as the 5 Ms, 8 Ps, or 5 Ss only are considered as guidelines.

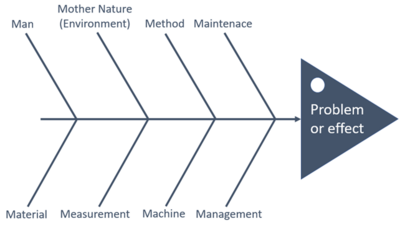

Oftentimes the 5 M’s, also known as 4 M’s and 1 E, Machine, Method, Material, Man, and Mother Nature (Environment), is used for evaluation of production and manufacturing processes. Sometimes additional main causes, “M’s”, are relevant to include in the Ishikawa Diagram, namely Measurement, Management, and Maintenance, and hence called the 8 M’s. The 5 M’s are the most commonly used framework for the Ishikawa Diagram.

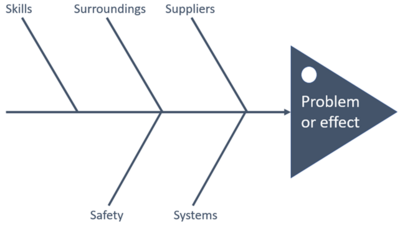

For problems related to services, the 4 Ss has been chosen as main causes. These are Suppliers, Skills, Systems, and Surroundings. Often a fifth S standing for Safety can be added as a main cause.

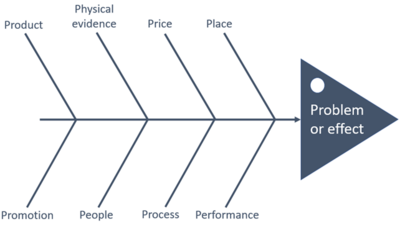

And finally, the 8 P’s are commonly used in product marketing and are used for identifying attributes for planning. The 8 P’s are Product, Price, Place, Promotion, People, Process, Physical evidence, and Performance.

The Ishikawa Diagram in Conjunction with Other Project Management Tools

Apart from using the Ishikawa Diagram in conjunction with the beforementioned seven basic tools of quality control used primarily for assuring product- and process quality and the five whys, the tool can also be applied in combination with for example failure mode and effect analysis (FMEA) and post-project reviews (PPR).

The FMEA tool is developed in the field of quality management. It has a systematic approach to try and foresee risks and failures that can happen in a system or project, and hereafter try to mitigate or avoid these risks by making contingency plans.[9] The tool is essentially a brainstorming exercise, where the potential causes of failure of the project or system are sought to be identified. There are typically five stages “Identify failure modes”, “Identify root causes”, “Identify failure effects”, “Prioritise” and “Develop contingency plans”. In more of the stages, the Ishikawa Diagram would be an extremely powerful tool to reach the root causes and thereby sustain quality and mitigate risk as well as help prioritise resources and time. The tool is very useful for planning projects and identifying risks and the obtained knowledge from using the tool can allow for a continuous improvement mechanism.[9]

Post project activities are performed to verify the outcomes and see if expected benefits were realised and thereby determine a project’s success.[2] The tool PPR is a tool for post-project evaluation and evaluate project results to improve future projects, methods, and practices.[10] It is essential to have a structured approach to conduct a PPR to be able to use the lessons learned in future projects to mitigate risks and improve quality. The Ishikawa Diagram can be used in conjunction with the PPR tool, to for example identify why the objective was not met or why the realised benefits were not as good as expected, and thereby promote a continuous learning and improvement mechanism by obtaining knowledge for future use.

Limitations

Despite the tools’ many advantages, it does, however, also have limitations. The usefulness and value obtained using the tool are completely reliant on the project team evaluating the problem or effect using the Ishikawa Diagram. The importance of gathering the right project team can therefore not be emphasised enough.

Since the Ishikawa Diagram is a visual tool, the more sub-causes that the project team identifies during the brainstorming session, the more visually cluttered the diagram will be. Moreover, all causes look equally important in the diagram at first sight as there is no method for illustrating the causes prioritising during the brainstorming. Thus, it becomes increasingly difficult to find and investigate the relevant root causes as the number of causes increases. Also, the more cluttered the diagram becomes, the harder it will be for the project team to identify interrelationships between the causes. Also, important causes can be overlooked if they are not recognised by any project member.

The identification- and prioritisation stage of the Ishikawa diagram is characterised by subjective opinions and not necessarily justified by the evidence. Hence, the root cause being solved may not be the actual reason for the problem. Lastly, it should be mentioned that the Ishikawa Diagram is a tool for identifying and analysing root causes of a given problem, but the tool does not provide any guidance on how to respond to the causes identified nor help in making contingency plans. Thus, it is highly recommended to use the tool in combination with other tools that can provide this type of support.

Annotated Bibliography

International Organization for Standardization. (2020). Project, programme and portfolio management – Guidance on project management (DS/ISO 21502:2020) Provides the international standards for project management and guidance on how to achieve and live up to the various standards in project management including quality management and risk management.

Project Management Institute. (2019). Standard for Risk Management in Portfolios, Programs, and Projects. Project Management Institute provides the Project Management Institutes standards for risk management in Portfolios, Programs, and Projects. The book is very informative and give guidance regarding the fundamentals, application, and principles of risk management.

Aldridge, E. (2022). Root Cause Analysis Steps PMP Exam Guide. Projectmanagementacademy.net gives an easy and thorough introduction to root cause analysis including benefits. Moreover, it provides a stepwise guide to conduct an Ishikawa Diagram and connects the five whys tool to the Ishikawa Diagram.

Wong, K. C., et al. (2016). Ishikawa Diagram. Quality Improvement in Behavioral Health (1st ed. pp. 119-132). Springer International Publishing. This chapter of the books ties the Ishikawa Diagram to various other project management tools including the failure mode and effect analysis tool for greater benefits.

Project Management Institute. (2021). A guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK guide) (7th ed.). Project Management Institute. This book provides an overall description of project management and all the elements that it involves which among these include risk- and quality management.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Aldridge, E. (2022). Root Cause Analysis Steps PMP Exam Guide. Projectmanagementacademy.net. https://projectmanagementacademy.net/resources/blog/root-cause-analysis-steps-pmp-exam-guide/. Accessed 20 Feb. 2022.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 International Organization for Standardization. (2020). Project, programme and portfolio management – Guidance on project management (DS/ISO 21502:2020). https://sd.ds.dk/Viewer?ProjectNr=M351700&Status=60.60.

- ↑ Wong, K. C., et al. (2016). Ishikawa Diagram. Quality Improvement in Behavioral Health (1st ed. pp. 119-132). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-26209-3_9.

- ↑ Liliana, L. (2016). A New Model of Ishikawa Diagram for Quality Assessment. Iop Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering — 2016, Volume 161, Issue 1, pp. 012099. Institute of Physics Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/161/1/012099.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Project Management Institute. (2021). A guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK guide) (7th ed.). Project Management Institute. https://app-knovel-com.proxy.findit.cvt.dk/kn/resources/kpSPMAGPMP/toc?kpromoter=federation.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 LBS Partners (2022). HOW TO MAKE AND USE A FISHBONE DIAGRAM TEMPLATE. Lbspartners.ie. https://www.lbspartners.ie/insights/how-to-make-and-use-a-fishbone-diagram/. Accessed 20 Feb. 2022.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 CMS.gov. (2022). Guidance for Performing Root Cause Analysis (RCA) with Performance Improvement Projects (PIPs). CMS.gov. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/provider-enrollment-and-certification/qapi/downloads/guidanceforrca.pdf. Accessed 20 Feb. 2022.

- ↑ City Process Management. (2008). Cause and Effect Analysis using the Ishikawa Fishbone & 5 Whys. cityprocessmanagement.com. http://www.cityprocessmanagement.com/Downloads/CPM_5Ys.pdf.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Tidd, J. and Bessant, J.(2014). Failure mode effect analysis (FMEA). Innovation Portal. http://www.innovation-portal.info/wp-content/uploads/FMEA.pdf

- ↑ Von Zedtwitz, M. (2002). Organizational learning through post-projects reviews in R&D. International Institute for Management Development. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1467-9310.00258/full