Managing projects in a functional organization

Developed by Casper Claudinger

Abstract

Functional organizations, where the employees are grouped based on skills and job type, are useful to increase knowledge sharing within the groups. E.g. a functional group with programmers allows the programmers to help and learn from one another during working hours. This results in more specialized groups with self-increasing skills, though limiting the connection between people with different skill sets and complicating project management. Divisional/project-based organizations, where the employees instead are divided into groups based on location, product or market, have a broad variety of people with different skills in each group. This allows for better interactions among the different skill sets during working hours and easier project management but takes away the knowledge sharing with like-minded people. [1]

This article highlights the structural and hierarchical challenges that project managers must deal with when doing projects in functional organizations and how it compares to other organizational structures. Projects are generally complex and require people with various skills to be done. Thus, the divisional organization structure seems like the better fit for projects, as the need for inter-departmental communication is far less crucial and induces lateral processes. In a functional organization, all departments involved with the project have to be in close communication with one another in order to maintain a common direction for the project. The functional structure puts the legitimate power in the hands of the functional managers and introduces complex vertical communication processes. This is where challenges with project management in functional organizations start and where the project manager becomes important.

Contents |

Introduction and background

Managers deal with numerous different challenges and problems when supervising the employees and trying to set and achieve departmental goals while also complying with the goals and strategy of the organization. This applies to both functional managers and divisional managers. In this article, the focus is on the challenges that follow with doing projects in functional organizations. The well-renowned standard for project management, PRINCE2, states that "Projects often cross the normal functional divisions within an organization [...]". [2] This means that in a functional organization, projects may sometimes be purely functional projects and can be contained within a functional group and supervised by the functional manager. In this case, there is no room for a project manager. However, most projects will be cross-functional and will often span every department of the organization and perhaps even external workforce.

In order to discuss the role of the project manager in a functional organization, it is necessary to understand what a functional organization is. The next section introduces the general types of organizational structures along with the roles of the project manager in each structure.

Organizational structure

The term "organizational structure" covers the formal system of task and job reporting relationships between employees and how the organization's resources should be spent to obtain its goals. The structure is determined by managers, typically based on the four factors described by the contingency theory: organizational environment, strategy, technology, and human resources. This process is described by the term "organizational design" which includes job design (the division of the tasks required to run the organization into jobs) and design of the organizational structure (the reporting relationships). Overall, there are two distinct types of organizational structures; divisional and functional. However, large and complex organizations can create matrix structures which combine divisional and structural elements (see Figure 1). The final design is determined so that it maximizes the efficiency and effectiveness of the organization.[1] These three structure types are presented below.

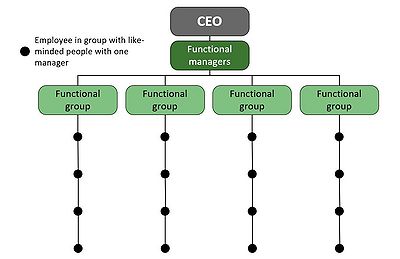

- Figure 1: Model displaying the structure of a functional organization. The models is created by the author of this article and is based on content from "Essentials of Contemporary Management" [1]

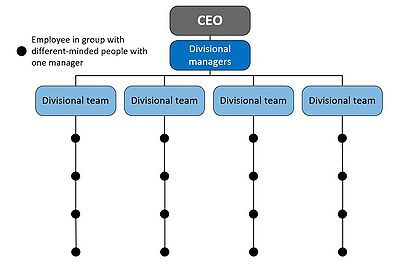

- Figure 2: Model displaying the structure of a divisional organization. The models is created by the author of this article and is based on content from "Essentials of Contemporary Management" [1]

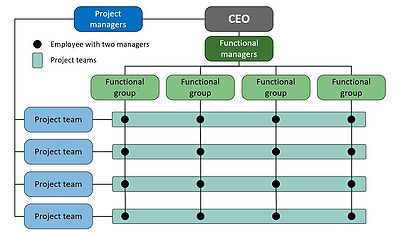

- Figure 3: Model displaying the matrix structure of a functional organization with cross-functional project teams. Each organization has to define a balance between managers to ensure a clear line of power. The model is created by the author of this article and is based on content from "Essentials of Contemporary Management"

Functional structure

Grouping the jobs in the organization based on skill requirements, so that employees with resembling skill sets work together, is the idea of the functional structure (see Figure 1). A functional organization is composed of all the departments that are required for the organization to deliver its products, being goods or services. This structure makes it easy for functional managers to evaluate the performance of the employees in their respective departments since all their employees can be evaluated on the same factors. Furthermore, each department can be more specialized due to knowledge-sharing among the employees.

[1]

A vehicle manufacturing company with a functional structure would include a marketing department, a procurement department, a production department, and an engineering department etc. The performance of each department in this structure would be higher compared to the divisional structure because e.g. the engineers in the engineering department are able to share knowledge and discuss tasks more easily - thereby increasing the knowledge of every engineer. Another benefit is that tasks or projects which are completed within functional departments might often share common attributes and will be completed faster due to the increased collaboration among like-minded employees.

Divisional/project based structure

In larger organizations, which begin to produce a wider range of goods or services and deal with a larger variety of customers, functional managers might become so busy supervising their departments and keeping up with departmental goals, that they lose sight of the organizational goals and strategy. This reduces efficiency and effectiveness and this is where the divisional structure becomes useful (see Figure 2). Rather than having large functional units dealing with large numbers of different tasks, divisional departments can be implemented to split the number of tasks out to e.g. product specific departments.

[1]

Instead of having a marketing department that sells all types of products from the organization, there would be departments for each product type employing a limited number of marketing experts along with production-, engineering-, and procurement experts specialized in the product of their department. The product manager would then have a more manageable amount of tasks to supervise. Though, the cost of this structure is the lack of knowledge-sharing which results in departments with reduced skill performance.

However, it is a necessary structure to keep the departments aligned with the organizational strategy and to provide the highest possible level of efficiency and effectiveness.

As a side benefit, doing cross-functional projects in a divisional structure can be easier, since a project can be contained within a single department instead of being cross-departmental. An organization that is built entirely upon teams doing cross-functional projects rather than day-to-day operations can thus also be considered as a divisional organization.

Matrix structure

Somewhere in between the functional and divisional structures lies a loosely defined matrix structure as described by PMI.[3] The matrix structure is an arbitrary combination between the functional and the divisional structures and has its benefits and disadvantages. According to PMI, there is no "better" structure generally speaking, but some organizational forms have better chances for working than others. Which one it will be is also affected by the type of tasks the organization will be performing. A classic matrix structure is a functional organization with cross-functional projects and project managers (see Figure 3). The main concern with the matrix structure is, that each employee involved with a project will answer to two managers - the functional manager and the project manager.

Managing projects in functional organizations

Now that the functional structure is presented, this section deals with projects and how they exist in functional organizations and how they are managed. The PRINCE2 standard[2] presents clear definitions of projects and project managers which are briefly presented in this section. The PMI standard, PMBOK[3], provides an extensive overview of project management and the role of the project manager. Some basic principles and definitions are presented below and challenges regarding project management in functional organizations are discussed.

Projects in functional structures

According to the PRINCE2 standard, the definition of a project is:

- “A temporary organization that is created for the purpose of delivering

one or more business products according to an agreed business case”. [2]

- “A temporary organization that is created for the purpose of delivering

It is important to distinguish between the term 'organization' when used in this article and when used in the standard. When used in this article, the term refers to a permanent business-like organization such as a company. When used in the PRINCE2 standard, it refers to the temporary concept of a project. So, the standard’s definition of a project is a temporary team created to deliver business products according to a business plan. The key point here is 'product'. If a team in a functional organization is to deliver a product, it would require people from all the departments in the organization. Thus, all projects in functional organizations are cross-functional and involve most, if not all, departments of the organization and will require project managers. An organization, that can do a project and deliver a product within a single department, will by definition be a product divisional organization.

The standard describes six project performance aspects that need to be managed: scope, timescales, costs, quality, risks, and benefits.[2] Since projects are cross-functional and all departments of the functional organization are involved, it becomes quite crucial to every project that there is a plan and that things are managed. Thus, project managers are essential in functional organizations, especially because the structure complicates that specific job.

Project managers in functional organizations

The before mentioned standard for project management, PRINCE2, has defined the role of the project manager as follows:

- "The project manager is responsible for the day-to-day management of the project within the constraints set out by the project board.

The project manager's prime responsibility is to ensure that the project produces the required products in accordance with the time,

cost, quality, scope, benefits and risk performance goals." [2]

- "The project manager is responsible for the day-to-day management of the project within the constraints set out by the project board.

As explained in the structure section, functional organizations have grouped the workers based on skill sets. In these organizations, the functional managers are given almost total legitimate power of the workers and resources in their departments. The project manager typically has very little, if any, legitimate power towards the workers and has to coordinate with the functional managers. The role of the project manager typically diminishes to the role of a project coordinator since the actual employee line management falls into the hands of the functional managers. Even so, the 'prime responsibility' of the project manager is intact - that is, providing the project deliverables in accordance with the performance goals, and there is still plenty of work to do besides managing the employees.

According to the PMI standard, the definition of project management is "the application of knowledge, skills, tools, and techniques to project activities to meet project requirements. Project management is accomplished through the appropriate application and integration of the project management processes identified for the project". [4] The standard states that there are 10 areas of knowledge, which are an extension of the six project performance aspects, that a project manager must deal with in every project.[5] These knowledge areas are listed in Table 1.

| Knowledge areas | Description |

|---|---|

| Integration | Identifying, defining, unifying and coordinating the processes of the Project Management Process Groups (which are presented in the next subsection). |

| Scope | Making sure that the project includes all the required work, and no excessive work, to complete the project successfully. |

| Schedule | Planning and controlling the timing of the tasks in the project and ensuring that the project is completed in time. |

| Cost | Planning, estimating, budgeting, financing, funding, managing, and controlling the costs of the project so it can be completed on budget. |

| Quality | Planning, managing, and controlling the project and product quality to ensure that the project deliverables meet the stakeholders' expectations. |

| Resource | Identify, acquire, and manage the resources needed to complete the project successfully. |

| Communications | Planning, collection, creation, distribution, storage, retrieval, management, control, monitoring, and ultimate disposition of project information. |

| Risk | Planning, identification, analysis, response planning, response, implementation, and monitoring risk on a project. |

| Procurement | Purchasing/acquiring products, services, or results needed from outside the project. |

| Stakeholder | Identifying people, groups, or organizations that could impact or be impacted by the project, analyzing expectations, developing management strategies for engaging the stakeholders in project decisions and execution. |

With 10 areas to focus on, that each involves planning and/or managing and controlling, the project manager has quite a lot to see to. To make sure things go smoothly as planned, it would be better if the project manager had as much control and legitimate power of the workers as possible in order to delegate the work as needed through quick lateral communication processes. However, the functional structure complicates this since the project manager has to delegate the work to the functional managers who in return will decide how the work is done in their departments. Thus, the functional structure introduces slower vertical communication processes to projects.

Project management in functional organizations

Challenges with management

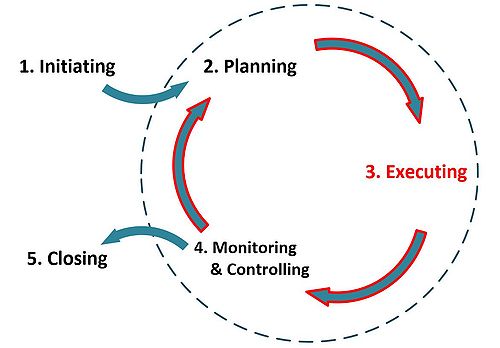

The PMI standard also describes five essential process groups of project management which project managers use to drive projects through their life-cycles: [4]

| Process Groups | Description |

|---|---|

| Initiating | This process group involves defining the project and obtaining authorization to start it by creating a project charter. This is done by creating the initial scope, identifying stakeholders, assigning a project manager and committing initial resources. Since authorization to the project and its scope has to be granted in this first process, an organizational benefit is that only projects which are aligned with the organization's strategic objectives will be allowed to exist. Also, the project can be aligned with the stakeholders' expectations and demands from the very beginning. |

| Planning | When the project is authorized, the details of the project have to be defined. This is a process group that initially involves a heavy workload for the manager. A project management plan has to be created, involving numerous planning processes such as project integration-, scope-, schedule-, cost-, quality-, resource-, communications-, procurement-, risk-, and stakeholder management. Once the project is started, increasing knowledge, risks or opportunities might change the circumstances of parts of the project. Thus, the manager might need to perform progressive elaboration as the project progresses. |

| Executing | When the planning processes have delivered a project management plan, the actual work on the project deliverables starts. For the project manager, this involves continuously coordinating resources, managing stakeholders and employees, and integrating and performing the project activities as stated in the project management plan to ensure that the project will fulfill its requirements. |

| Monitoring and Controlling | This process group consists of project tracking-, viewing-, and regulating processes. It is necessary to identify areas of the project in which changes to the plan are required, and then to react and initiate relevant regulations or corrections. This is called progressive elaboration and is done by collecting performance data during the project and reporting it in form of performance measures. It is important to compare the performance measures to the planned performance from the project management plan, and dealing with possible variances by doing appropriate corrective actions. The purpose is to make sure that the project progresses and performs as planned from start to end. |

| Closing | The last process group only contains one process that closes the project appropriately. This is to make sure that all phases and all process groups are finished and to formally sign off the project. An evaluation of the project is typically done to find and learn from any positive and negative aspects that might be useful for future projects. |

Combining the 10 knowledge areas with the five process groups produces a matrix with the basic project management tasks that project managers perform according to PMI.[5] This matrix is shown in Table 3, where the red column marks the process group and tasks which are most impacted by the functional structure. The Executing Process Group involves the line management of the employees which the project manager does not have the legitimate power to do, as discussed above. Looking at Table 3, it becomes very clear exactly how much work the project manager still has to tend to in the functional structure. All knowledge areas require extensive planning, almost all areas require controlling, and then there is the management of the functional managers on top of that.

| Process Groups | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initiating | Planning | Executing | Monitoring and controlling | Closing | ||

| Knowledge Areas | Integration | Develop project charter. | Develop project management plan. | Direct and manage project work. | Monitor and control project work. Perform integrated change control. | |

| Scope | Plan scope management. Collect requirements. Define scope. Create WBS. | Validate and control scope. | ||||

| Schedule | Plan schedule management. Define, sequence and estimate activities. Develop schedule. | Control schedule. | ||||

| Cost | Plan cost management. Estimate costs. Determine budget. | Control costs. | ||||

| Quality | Plan quality management. | Perform quality assurance. | Control quality. | |||

| Resource | Plan resource management. | Acquire, develop and manage project team. | ||||

| Communications | Plan communications. | Manage communications. | Control communications. | |||

| Risk | Identify and analyse risks. Plan risk response. | Control risks. | ||||

| Procurement | Plan procurement management. | Conduct procurements. | Control procurements. | Close procurements. | ||

| Stakeholder | Identify stakeholders. | Plan stakeholder management. | Manage stakeholder engagement. | Control stakeholder engagement. | ||

The Planning, Executing and Controlling processes are ongoing through a project and are mutually dependent. Thus, if one process group gets impaired it will have consequences for the other process groups as well. The project manager must have close communication with all the functional managers to get regular updates on the Executing and Monitoring processes. This information is required for the Controlling process which evaluates the planned performance against the actual performance within the functional groups. Then the project manager can plan changes or alterations to the project plan as needed, and finally, these changes have to be communicated back to the functional managers and implemented correctly before the cycle starts again (see Figure 4). For large and complex projects, which require intensive management, the importance/impact and the amount of these interactions between the managers are significantly increased. The complex multi-step vertical communication processes might then become sources of project delays.

Limitations of functional- and matrix organizations

From an ideal point of view, the functional structure provides the best performing departments. When doing cross-functional projects, however, challenges appear in the functional structure. In most projects, the project manager is deeply involved with all of the process groups, but in pure functional organizations the functional managers, who have more legitimate power, are responsible for the execution and monitoring processes by managing their employees. Here, the project manager's task is to coordinate between the functional groups and to make agreements with the functional managers so the project progresses. The project manager is still mainly responsible for the initiation, planning, controlling and closing processes, but he/she cannot manage and monitor the workers. Thus, a portion of the project management is out of the project manager's hands, and communication and cooperation with the functional managers become crucial.

The structure can also have negative impacts on the employees. This way of doing projects is linked with a risk regarding the workers involved with the project. If they are not working alongside other people assigned to the project, but are working from their respective departments, they might lose focus or sight of scope on the project. Furthermore, the functional managers might be caught up with their own department, and tend not to prioritize resources on the project which will potentially cause delays in the project.

This can be resolved by breaking away from the functional structure by giving the project manager more legitimate power. The functional manager might convince himself that the tasks within his department are of higher priority than the project, while the project manager has it the other way around. This can put stress on the employees since they would not know who to answer to, which might reduce their overall performance and job satisfaction. Also, their focus would be split in two directions which further reduces their performance. When breaking away from the functional structure, every employee is already used to respond to their functional manager and is possibly occupied with certain departmental tasks that the functional manager has planned. When the employee is assigned part-time to a project with a project manager, the employee now responds to two managers.

According to the PRINCE2 standard, a lacking hierarchy among the managers, or if the managers cannot come to an agreement regarding the division of the employee's working hours, can be a source of conflict within organizations.[6] This often results with the project manager having to answer to the functional manager, and that affects the complexity of project communication management as discussed earlier.

Sometimes, organizations can temporarily put legitimate power in the hands of the project manager by partly or entirely designating people from the functional groups temporarily to the project, removing them from their respective departments and bringing them together. They are then to answer to the project manager only, for the duration of the project, and their focus is restored. This also puts the executing and monitoring processes back in the hands of the project manager. However, organizations with shorter projects will tend to move the employees around a lot, which can cause frustration and cause the employees to lose their feeling of affiliation toward any part of the organization. Organizations with longer projects will obtain greater benefits from this solution, as long as the employees agree to join the projects.

If, on the other hand, the project managers are given more legitimate power than the functional managers, the organization has transformed into a divisional project structure with cross-divisional functional groups or with no functional groups at all. As mentioned at the beginning of the article, this removes the knowledge-sharing among like-minded employees, since they will spend most or all of their working hours with a diverse project team. The high-end performance of the organization will then drop, but the project manager gets full control of the project. Thus, the benefit is that projects can be managed more easily with lateral communication processes, but organizations which address the market with top-of-the-art products or services might find that this structure has a negative impact on their competitive strength.

Each organization, the top management has to determine a clear strategy for prioritizing legitimate power between functional tasks and projects. This can vary from department to department and between projects with respect to program and portfolio management. Thus, organizations who want to perform consistently well have to stay flexible with respect to the managerial hierarchy by having a dynamic balance of power and authority between the managers - regardless of the chosen organizational structure.

Annotated bibliography

The Essentials of Contemporary Management, Chapter 7 (Sixth Edition) (J. M. G. Gareth R. Jones)

This chapter describes the process of which managers choose organizational structures and what these structures are. It describes benefits and disadvantages to the common structure types and why managers need to solve related issues to successfully provide project deliverables.

Managing Successful Projects with PRINCE2, Chapter 2 (TSO)

This chapter contains the definitions of projects and project management in the PRINCE2 standard and describes the role of the project manager in general.

The matrix organization (PMI)

This online site describes the matrix organization structure according to the PMI standard, and the types of hierarchical challenges that arise in this structure class.

Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide) (6th Edition) - Part I (PMI)

This part of the book deals with the role of the project manager and the ten knowledge areas required of the project manager, including various tools, inputs, and outputs regarding those areas.

Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide) (6th Edition) - Part II (PMI)

This part of the book deals with the actual project management, introducing the five process groups of project management that the project manager uses to drive projects. It presents the underlying processes within each group and provides some tools to do them.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 J. M. G. Gareth R. Jones, Essentials of Contemporary Management, Sixth edit. New York, NY 10121: McGraw-Hill Education, 2015, Chapter 7.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Managing Successful Projects with PRINCE2. London (London): TSO, 2017, Chapter 2.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Stuckenbruck, L. C. (1979). The matrix organization. Project Management Quarterly, 10(3), 21–33.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Project Management Institute, Inc.. (2017). Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide) (6th Edition) - Part II. The Standard for Project Management. Project Management Institute, Inc. (PMI). Retrieved from https://app.knovel.com/hotlink/pdf/id:kt011DXPR1/guide-project-management/part-ii-standard-project

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Project Management Institute, Inc.. (2017). Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide) (6th Edition) - Part I. Project Management Institute, Inc. (PMI). Retrieved from https://app.knovel.com/hotlink/pdf/id:kt011DXQ02/guide-project-management/guide-proj-project-management-36

- ↑ Managing Successful Projects with PRINCE2. London (London): TSO, 2017, Chapter 7.