Overcoming the Planning Paradox

Contents |

Abstract

This article will explore productive approaches to dealing with the Planning Paradox.

"No plan of operations extends with any certainty beyond the first encounter with the main enemy forces.

Only the layman believes that in the course of a campaign he sees the consistent implementation of an

original thought that has been considered in advance in every detail and retained to the end."

~Field Marshal Moltke the Elder [1]

The point of departure for this analysis will be a civilian reading of military theory[2], grounded in the appreciation that war is an endeavor with dynamic and unforgiving external constraints where leadership complacency is punished severely.

The following is based on the premise that civilian organizations can learn from experienced military leaders accustomed to navigating volatile situations.[3]

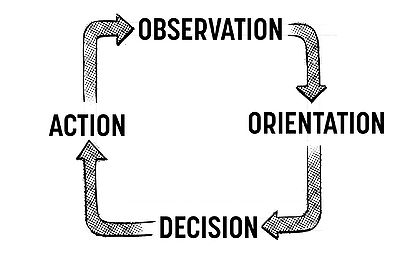

The abstraction level for the analysis in a peaceful context is to seek inspiration in more wicked problems, on how to embrace uncertainty and adapt to surprises in a structured way that touches on all four course dimensions.[4] On multiple scales, a popular strategy appears to be reducing organizational complexity by means of flattening leadership structures where swift action is required.[5] This principle is also deployed where every member of a team has the competencies to dynamically transfer leadership based on who has the most situational awareness. The intent of this is to shorten the collective decision cycle or OODA loop[2] in a dynamic situation, to avoid bottle-necking decision making in a single individual who might be denied sufficient situational awareness to make a productive decision. Here a short summary of factors for cohesion will be provided as well.

In a project scale perspective, the wide array of Agile Frameworks[6] have a common aim: Shorten development cycles to face reality in the form of stakeholder feedback on MVP’s. The intent of this strategy is to reality check assumptions and self-correct away from sunk-cost behavior with minimum investment. Here, dysfunctional implementations of Scrum[7] will be explored as a warning against unreflected framework deployment.

Finally, on the Portfolio level this article will also explore the risks of Path Dependence[8] with respect to situational agility. The case studies for this exploration will focus on hesitancies to exploit technological salients[9] that big organizations otherwise appeared to be poised to dominate[10]. This analysis will respect the good intentions of the leadership, attempting to contextualize their hesitations with the organizational complexity they had to work with as well as the corporate cultures they had to navigate. These examples will be picked up with a conclusion on the relative merits and limitations of the tools explored, followed by a recommendations to continually adapt leadership strategies and framework deployment to the situation at hand and keep organizational structure ready for changes as the situation permits.

Decision Making Lessons from a Fighter Pilot

John Richard Boyd was a United States Airforce (USAF) fighter pilot who, after his combat deployment in Korea, got his nickname "forty seconds" from a standing bet he made as an instructor in the USAF Fighter Weapons School(FWS). The bet was that he, within forty seconds, could defeat an opponent from a position of disadvantage in Air Combat Maneuvering (ACM). After instructing he went on to contribute to the development of the F-15 Eagle, as well as laying the strategic foundations for the USAF Lightweight Fighter programme with his Energy-Maneuverability theory of aerial combat. His true legacy is one of tactical and strategical thinking. He was very critical of rigid structure of command and other symptoms of inflexibility. An example of this is found in his "Patterns of Conflict" presentation that compares Napoleon Bonaparte's early and late tactics, scolding the late Emperor for his top-down approach to tactics. His critique was that Napoleons rigid flow of orders was a tactical waste of sound strategy, and that the lack of afforded initiative to the lower parts of the organization was a key factor in his defeat.

A key concept underpinning Boyd's strategic and tactical teachings is his decision cycle, better known as the OODA loop developed for aerial combat decision making. It is an abbreviation for Observation, Orientation, Decision and Action: First, information is gathered about the situation. Second, the actor must rely on experience to orientate themselves in the situation. Third, a decision must be made before finally acting. This cycle repeats continuously, and Boyd's central point with the decision cycle was that if two adversaries with equal capabilities with respects to skill and resources meet in conflict: Then the pilot who closes the OODA loop the fastest wins. Note that action itself is within the loop as a point of order that needs to be completed before gathering more information.

- Observation: Raw information about the situation is collected.

- Orientation: The information is parsed through experience, with subjective analysis of what might happen.

- Decision: A review of possible courses of action ending in selection.

- Action: Decision enactment.

Considering the concept of Path Dependency - and by extension the sunk cost fallacy - through Boyd's decision cycle the error becomes glaring: The OODA-loop is not closed and re-initiated, but the actor remains in the last phase - stuck on action without further review of the situation. The situational awareness is not maintained and the action becomes blind and predictable to adversarial response.

Any given problem or set of problems might develop into a threat, even without adversarial and malicious intent. For example he discovery of a "unknown-unknown" after a project has been scoped and initiated presents a similar management challenge. Continual usage of the Boyd Cycle is a deceptively simple framework for dealing with a developing situation. The OODA-loop is intended to be applied at all levels, from the operational, through the tactical and up to the strategic level. Abstracted to a civilian context and in summary: The OODA-loop must develop as fast as, or quicker than, the problem being dealt with.[2]

Organizational Structure - Perils and Opportunities

What is strategy? A mental tapestry of changing intentions for harmonizing and focusing our efforts as a basis for realizing some aim or purpose in an unfolding and often unforeseen world of many bewildering events and many contending interests. ~John Boyd

Boyd's approach to overcoming bewilderment was on one hand to be adaptable enough to become the unforseen factor for the adversary, on the other hand to organize for that adaptability and to be oriented toward acting on relevant contingencies. This readiness to adapt operational action to realize tactical and strategic objectives is central. Rigidity in action in a changing environment risks misalignment of the effort with the objective.

Management must question core rigidities and foster dynamic capabilities to increase capacity for change in the face of disruption.[11]

NASA & USN

After the Columbia space shuttle disaster and the following Senate hearings, where the testimony of Admiral Rickover prompted a collaboration between NASA and USN. Rickover managed the Naval Nuclear Reactor (NR) programme, successfully deploying principles that allowed for safe operation of reactors. This lead to a collaboration known NASA/Navy Benchmarking Exchange, where practices in the NR programme were examined by the NASA to learn how the USN systematically mitigated the risks of running and maintaining high risk technology without accidents.

Among the learnings was that NR had embedded safety processes within the organization, such that a quality or safety office was functionally unnecessary. The organization is relatively flat with easy access to the director, and the organization promotes voicing diverse and differing opinions. Here it was noted that when no differing opinions are present, managers were responsible for critical examination of the issue that actively encouraged such opinions. Recruitment and training of highly qualified professionals is relied upon, to keep them personally accountable and responsible for operational safety. The institution had embedded a closed loop learning process based on technical requirements that feed into the foundation of future design specifications.

These findings led to opportunities for NASA to consider alternative organizational and management approaches for future programmes, as well as approaches for safety critical decision making. Selected USN submarine approaches to safety procedures and fora for free and critical discussion of critical safety issues.

The practices and organization of USN was directly addressing the objective of safe operation, not relegating this as a seperate activity or oversight entity, but embedding risk analysis into the fabric of operations.[5]

Kodak

Kodak was a very large film company, highly technology focused and specialized in chemically producing photographs. When the technological salient began closing to provide the opportunity to make digital photography, Kodak did not seize their brand opportunity to stay "picture company" number one. The company considered themselves tied to their technology of choice, and the emergent technology became the competitor. Kodak had the finest production facilities for producing film, and that production capability became their center of identity and probably the reason why they acted like the the new technology was an adversarial force. To their credit, they did not possess the electronics capabilities of other Japanese brands like Toshiba. [10]

Kodak did invest intensively in digital photography, but was unable to capitalize on the investment due to core rigidities in the organization. The culture of the organization and a middle management specialized in driving deprecated technology, did not leave the company with enough dynamic capabilities to shift from chemical to digital technology. The culture of the organization was polite, bureaucratic and risk-averse. A culture deeply embedded after more than a century of success in the film business. A change in objective and massive funding from the upper management was not enough to refactor the company as quickly and drastically as the market demanded. The required shift from being a film company to becoming a picture company to stay competitive on the market, required them to all but shelf their entire portfolio and discontinuously realign project and program capabilities to a completely different technology. They were unable to close the decision loop fast enough throughout the organizational layers, nor aligning on what the necessary consequences of the situation at hand were. [12]

Inflexible Agility

The concept of an agile framework can be argued to be a misnomer, in the sense that the terse principles of the agile manifesto[13] is the outline of a philosophy that rebels against the characteristics of doctrinal frameworks.

- Individuals and interactions over processes and tools

- Working software over comprehensive documentation

- Customer collaboration over contract negotiation

- Responding to change over following a plan

The first point that team dynamics are valued higher than the processes and tools leveraged to achieve the objective. The official Scrum website warns against “Mechanical” Scrum, being described as simply going through the motions, ticking the boxes, and performing the ritual as set out by the Scrum guide.[14] Practitioners are encouraged to shift their focus beyond the cycle, pointing to a set of values as well as the agile manifesto to orient the framework toward outcomes. Adherence to the certified cycle remains a recipe to keep development “agile”. Zooming out to the larger, Scaled Agile framework (SAFe), also bearing a certificate to implement agile processes in larger organizations promise a structural, process-based recipe for agility, incorporating a palette of tools and processes. [15]

The certifications imply that there is a correct way to be agile, within a given structure that suggests that following the recipe will result in agility. The danger with these approaches that critics such as Jeff Gothelf and Allen Holub point to, is that dogmatic adherence to these processes and tool implementations is missing the point of agility entirely. The focus of these frameworks pivot back to predictable delivery over flexibility in planning and course correction. A predetermined set of features becomes the focus over the objective of delivering customer success.

“SAFe gives the illusion of “adopting agile” while allowing familiar management processes to remain intact. In a world of rapid continuous change, evolving consumer consumption patterns, geopolitical instability and exponential technological advancements this way of working is unsustainable.”

- Jeff Gothelf

If these practices are taken up without critical reflection, tools and processes risk becoming impediments to the effectiveness of the deliveries in the pursuit of efficient development. Balancing these two concepts is at the core of Lean, Toyotas industrial structuring that is poised toward servant leadership and cutting out any activity that does not bring value to the end user. The concept of servant leadership is a salient point here, the practice of continuously adapting tools and processes to the trusted, professional practitioners delivering the value.

Conclusion - Contextual Framework Implementation

The Boyd Cycle is a framework for understanding and responding effectively to rapidly changing and uncertain situations. These principles can be applied to question whether competencies have become core rigidities and to foster dynamic capabilities that enhance an organization's capacity for change in the face of disruption.

- Observe: When questioning whether competencies have become core rigidities, it is crucial to assess whether the existing competencies and strengths of an organization are still relevant and effective in the current context. This involves monitoring market trends, customer preferences, emerging technologies, and competitive landscape to identify potential disruptions and changes that might render existing competencies obsolete.

- Orient: Organizations should evaluate whether their current competencies align with the emerging trends and future demands. They need to question whether their existing competencies have limited their ability to adapt to new challenges.

- Decide: Based on the analysis and interpretation of information, organizations must make informed decisions regarding the necessary changes to their competencies. This could involve identifying new competencies required to respond to disruptions or reevaluating existing ones to make them more flexible and adaptable. Decisions should be made swiftly, as delay could lead to missed opportunities or increased vulnerability to disruption.

- Act: Organizations should take proactive steps to develop and acquire the required competencies, which might involve investing in training programs, hiring new talent, forming partnerships, or exploring new technologies. The aim is to develop dynamic capabilities that enhance the organization's ability to respond quickly and effectively to disruptive changes in the environment.

By applying Boyd's principles, organizations can challenge the notion that competencies have become core rigidities. While competencies may have contributed to an organization's success in the past, they can also limit its ability to adapt and innovate in the face of disruption. Dynamic capabilities, on the other hand, enable organizations to continuously learn, evolve, and adjust their competencies to meet changing market demands.

In summary, by using Boyd's principles of adaptive decision-making, organizations can question the role of competencies as core rigidities and actively foster dynamic capabilities to increase their capacity for change.

References

- ↑ H. G. Moltke, Moltkes militärische Werke (E. S. Mittler, 1900) - Digitized by the University of Virginia, 2009

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 F. Osinga, Science, Strategy and War: The Strategic Theory of John Boyd (Eburon Academic Publishers 2005)

- ↑ [http://commdocs.house.gov/committees/science/hsy90160.000/hsy90160_0.htm] Hearing on the Organizational Challenges in NASA in the wake of the Columbia Disaster: Testimony of Adm. Rickover

- ↑ [https://www.doing-projects.org/perspectives] Doing Projects: Perspectives

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 ['https://www.nasa.gov%2Fpdf%2F45608main_NNBE_Progress_Report2_7-15-03.pdf'] NASA/Navy Benchmarking Exchange (NNBE) Vol.II (NNBE 2003)

- ↑ ['http://wiki.doing-projects.org/index.php/Agile_Project_Management']Agile Project Management

- ↑ ['https://ronjeffries.com/articles/016-09ff/defense/']Ron Jeffries, Dark Scrum (Blog Post 2016)

- ↑ ['https://www.britannica.com/topic/path-dependence']Britannica: Path Dependence Definition

- ↑ ['https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/social-sciences/actor-network-theory']Science-Direct Overview: Actor Network Theory

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Prenatt et al.How underdeveloped decision making and poor leadership choices led Kodak into bankrupcy (2015)

- ↑ Christensen, C. M., & Overdorf, M. (2000). Meeting the Challenge of Disruptive Change. Research Technology Management, 43(4), 63–63.

- ↑ Lucas, H. C., & Goh, J. M. (2009). Disruptive technology: How Kodak missed the digital photography revolution. Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 18(1), 46–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsis.2009.01.002

- ↑ Manifesto for Agile Software Development. (n.d.). https://agilemanifesto.org/

- ↑ What is professional scrum?. Scrum.org. (n.d.). https://www.scrum.org/what-professional-scrum

- ↑ Scaled Agile, inc. scaledadgileframework.com (n.d.). https://scaledagileframework.com/