Participatory Design

By Henrik Svensson

Contents |

Abstract

Participatory Design is a design approach that heavily emphasizes involvement with key stakeholders, particularly end-users, during the development of products, services and systems. This article provides a high-level overview of Participatory Design from a project management perspective and details key concepts, methodologies and limitations of the field. The article also shows how utilizing a participatory design approach can lead to better project outcomes, including improving the development of more innovative solutions.

Background

In order to understand the core concepts of Participatory Design, it is useful to first look into the historical context in which it emerged. The origins of Participatory Design can be traced back to the early 1960s, where the Swedish trade union movement recognized a need to give workers the opportunity to have a greater influence on the design of their work environment. The first explicit attempts to utilize Participatory Design emerged in collaboration with the Norwegian Metal Workers Union in Scandinavia during the early 1970s[1]. The initial focus of Participatory Design was on the concerns and values of the labor union in the context of developing computer-based systems in socially democratic countries[1] [2]. This approach garnered international interest as the early research showed promising results, had a strong theoretical foundation, and provided practitioners with concrete tools and methods with which to facilitate participatory Design in projects. Over the coming decades, Participatory Design would evolve to include a wide range of different fields [2].

Big Idea

Participatory Design is a user-centered collaborative design approach that aims to involve all relevant stakeholders in the design process, enabling them to become co-creators of products and services[3]. Co-creation is a key aspect of Participatory Design, involving the creation of new knowledge and solutions through collaboration between designers and stakeholders[4]. This approach gives designers the ability to understand and empower users by giving them a voice in the design process, allowing them to contribute their knowledge and expertise to the development of products and services that meet their needs[5]. The pioneers of Participatory Design recognized that while many engineers tend to focus on the technical aspects of a system, central to the design process within any organization is their political nature[6]. The asymmetry of power in organizations often lead to a mismatch between the demands of management and the needs of the workers who end up using the system being designed. The principles of Participatory Design align with Jonathan Grudin's (an influential computer and principal design researcher) assertion that the design of technology should focus on the user and their needs, rather than being solely driven by technical considerations[7].

Application

According to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK) guide, one of the keys to ensuring project success is to "Establish and maintain appropriate communication and engagement with stakeholders" [8]. Participatory Design can be applied to project management by offering tools for involving stakeholders in the design and decision-making process, facilitating communication between stakeholders, and generating innovative solutions[9] [10]. This involvement can lead to more effective outcomes by ensuring that the needs and concerns of stakeholders are taken into account.[3] PD can also help to build trust and collaboration among stakeholders, leading to more positive relationships and better project outcomes. [11] Participatory Design has also been shown to be an effective method for exploring the market to match products/services with demand [12].

In order to reap the potential rewards of utilizing Participatory Design in projects, one must first understand the Participatory Design process.

Participatory Design Process

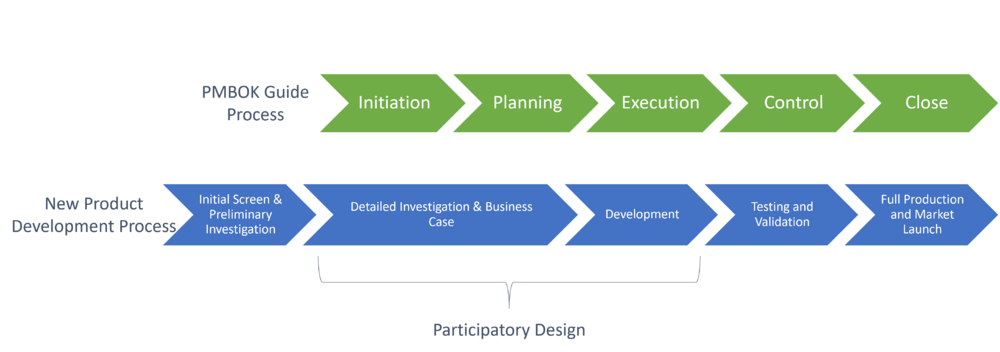

To use Participatory Design effectively in project management, it is important to follow a structured process that involves key stakeholders at all stages of the design process. This can be challenging since Participatory Design is still very much a field in flux, and there is no standardized process in place. However, when looking through how Participatory Design projects have been conducted so far, the fundamental stages of the process become clear. This process typically involves several stages, the core of which are described below and shown in figure 1: [5]

1. Initial Exploration of Work

This stage involves system designers meeting the end-users to begin to better understand their ways of working (or needs as a consumer). The focus of this initial exploration tends to be on workflow, technology, procedures, team dynamics, and other relevant elements of the work environment.

2. Discovery

Next, the design team and users work together to produce insight about the prioritization and organization of work in order to envision an ideal future workplace or system. Usually, this stage of the process is done in-person, as many of the Participatory Design practices rely on sharing the same physical space with the two parties.

3. Prototyping

Here the participants utilize an iterative approach to create a model of the system in the ideal future state.

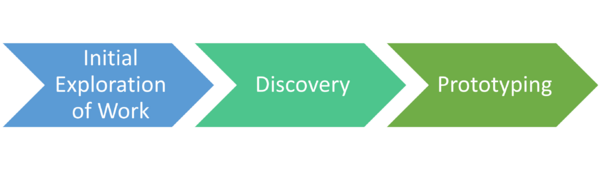

In the Context of Project Management

The PMBOK guide outlines two categories of project processes: project management processes, and product-oriented processes[13]. While the focus of the guide is on project management processes, they argue that "...product-oriented processes ... should not be ignored by the project manager and project team. Project management processes and product-oriented processes overlap and interact throughout the life of a project." Since project management integrates integrates both processes, project managers need to have an understanding of both[13]. In 2016, the Project Management Institute (PMI) released a white paper exploring the connection between these processes and how traditional project management can be applied to product development [14]. Figure 2 shows the mapping of the traditional project management process to the product development process [14] and an indication of where participatory design fits into these processes.

While Participatory Design is generally applied to product-oriented processes, there is interesting work to be done about finding more ways for how to it could be used to address project management processes.

Participatory Design Techniques, Methods, and Practices

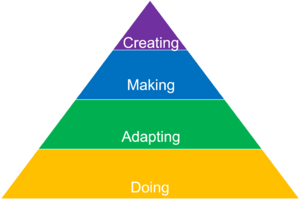

When applying Participatory Design to project management, it is important to recognize the role and experience of various stakeholders in the design process. For example, not all beneficiaries of a project outcome are able to play a co-creative role in its design. It largely depends on the interest, expertise, and creativity of the stakeholder. When it comes to co-designing with users, it's important to engage those with high levels of creativity when it comes to design. Creating is defined by an inspired motivation to express creatively. Making is more about one's ability and skill. With adapting, one tries to integrate something make it their own. The doing level reflects the desire to just get the thing done. Generally speaking, the higher level of creativity, the more the user will be able to contribute positively to the project outcome[4].

Participatory Design involves a range of methods to support collaboration between designers and stakeholders[3]. When considering which methods to utilize, a project manager should take into account the context in which the tools are used:

Probes, Toolkits, & Prototypes

Probes, Toolkits, and Prototypes are described in detail in Sanders and Strappers (2014) similarly titled article[4]. They are a related set of methods to facilitate user and other stakeholder engagement in the design process.

Probes are designed to explore the context of use and generate new insights into user needs and behaviors. They can be anything that elicits a response from the stakeholder. The purpose is to inspire the system designer based upon the reaction created by the probe. Probes can take various forms including empty postcards, diaries, workbooks, or games. They are generally completed individually and sent back to the designers who created them. Probes are typically used in the early stages of the design process [4].

Toolkits are sets of tools and resources that are designed to support collaboration between designers and stakeholders by creating artifacts of a future state. They are designed specifically for each project and give the user or other stakeholder the tools to codesign with physical components. Toolkits are usually constructed in 2D or 3D using components such as blocks, wires, words, or pictures. This process is usually more guided than the probing process and is situated slightly further down the design timeline[4].

Prototypes are physical or digital models of a design that are used to test and refine ideas. They generally are used in later stages of design after designers have reached a deeper understanding of the relevant stakeholder requirements. They can be made from basic resources such as clay and wood, or be created in the digital space. A valuable aspect of this approach is that stakeholders can quickly create a working version of their ideas to share with other stakeholders who then can provide input. This helps in exploring how feasible the design to see if it should be pursued further[4].

Inspiration Card Workshops

Halskov and Dalsgård (2006) developed a Participatory Design method, known as inspiration card workshops, that can help generate ideas and facilitate communication between designers and stakeholders[10]. In these workshops, participants are presented with a series of cards that contain prompts or images related to the design problem. Participants use these cards to generate ideas and discuss potential solutions.

Inspiration cards are typically used in the early-middle stages of the design phase and are more useful before engaging in prototyping. They are split up into two categories, domain and technology cards. In preparation for an inspiration card workshop, researchers and designers conduct studies regarding the context of the project to create domain cards. In parallel, they also look into how different technology could be applied in the design to create technology cards. During the workshop, the cards are presented and then participants work together to create posters that capture design ideas using the inspiration cards. Halskov and Dalsgård note that this works best for groups of 4-6.[10]

Findings from this research showed how the outcome depended heavily on the participants and how the workshop was set up. The best results occurred when participants were familiar with each other and the creative process, and had relevant insight or expertise in the domain in which the project occurred. Overall, "The Inspiration Cards have clearly stimulated an innovative and productive process, and we have observed that the design concepts developed generally find a suitable balance between being innovative, and realistic in terms of implementation." [10]

Proxies

The use of proxies in Participatory Design are useful when, for one reason or another, a key stakeholder (usually an end-user) is unable to contribute in codesign. Users such as young children or people with disabilities may be unable to participate in the design process, but if their needs are relevant to the project it's important to ensure their perspective is somehow included. Proxies deliver on this necessity by leveraging the expertise of individuals who have expert understanding of the target group. For example, in the development of a device intended to aid those with aphasia (a language disorder that makes communication difficult) Participatory Design researchers worked with people who were deeply knowledgeable about the disorder and who were actively working with patients suffering from it[15]. These individuals were speech therapists who had a deep understanding of the needs of someone with aphasia and were therefore invaluable in the design process of the product designed to help these individuals.

Future Workshops

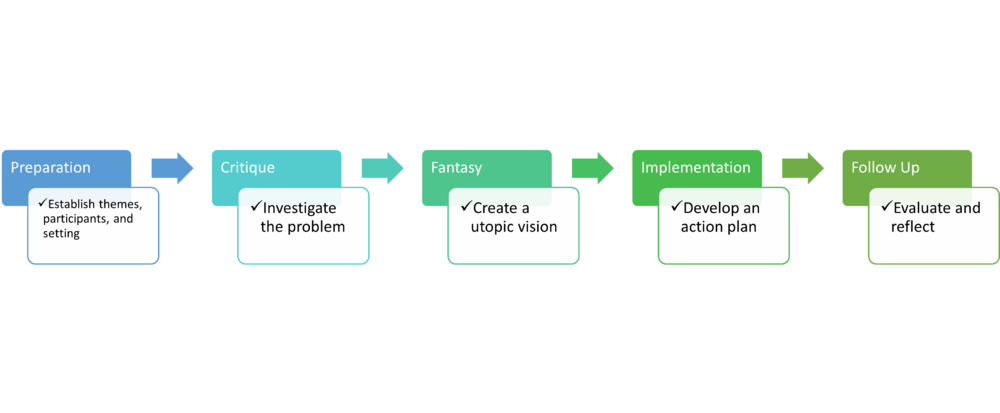

Future workshops are a well-known Participatory Design method that was originally used as a tool to help politically oppressed groups define a desired future state and find ways to move toward that goal[16]. Future workshops are broken down into 5 distinct phase (shown in Figure 4) and explored in the following section[17].

1. Preparation

Facilitators and organizers discuss the key stakeholders who should participate in the workshop, themes, and setting. According to Vidal, "This is a crucial phase because many problems that arise during the workshop are usually due to bad planning, poor organization and/or unsuitable physical environment."

2. Critique

During this phase, brainstorming is typically utilized to generate to deeply investigate the area of the problem. Then ideas are grouped into a structure related to the main themes.

3. Fantasy

Then participants are encouraged to imagine the best-case scenario when it comes to an ideal future state. An important characteristic of this phase is the removal of critique completely. Participants should feel free to explore ideas without being judged for their imaginal engagement. This phase develops synergy within the group and allows for consensus to be reached on ideas for moving forward.

4. Implementation

Here the critical eye is again a useful tool for evaluating the feasibility of proposed solutions and finding practical ways to move forward. The achievable ideas can be distilled down through further discussion and research into the related areas. The main output of this phase is the action plan which details the steps to reach the desired end state.

5. Follow Up

Finally, a final report is formulated containing all of the relevant information of the process and the action plan. This phase should also include an evaluation of the process itself so facilitators can further improve the methodology for conducting the workshops.

Ethnographic Studies

Ethnographic study involves observing stakeholders in their normal environment doing their daily work in order to develop systems that facilitate the activities of these stakeholders. This allows designers to gain insight into the context of use and identify any pain points or areas of difficulty. The designer first seeks to understand the user's point of view and ways of working before offering solutions. Some of the key aspects of ethnographic study are: focusing on the relationship between parts, withholding judgements about efficacy (using descriptive instead of prescriptive language), and looking through the lens of the participant. Common specific methods within this area are observation, interviewing and video analysis[18].

Cognitive Task Analysis

Cognitive task analysis is a Participatory Design practice that involves breaking down complex tasks into smaller steps to understand how people approach them. This involves working with stakeholders to identify the steps involved in a task, the decision points, and the strategies people use to accomplish the task. This helps designers understand how people approach a task and identify opportunities for improvement.

Analogous Inspiration

Analogous inspiration involves looking to other domains or industries for inspiration and ideas. This can involve looking at successful products, services, or experiences in other fields and adapting them to the current design challenge. Analogous inspiration can help designers think outside the box and generate innovative ideas.

These Participatory Design practices are commonly used by designers and are typically combined with other design methods and techniques to create a holistic design approach that is centered on the needs and experiences of stakeholders.

Limitations

Some common concerns regarding the field of Participatory Design[2] :

Lack of Clarity

There can be confusion around the terms used in Participatory Design, as the field has evolved over time and different terms have been used to describe similar concepts. This can lead to a lack of clarity and a misunderstanding of the field. There is a need for greater standardization of the language and terminology used in Participatory Design to reduce confusion and promote a shared understanding[2].

Sustainability

While Participatory Design can be an effective way to involve stakeholders in the design process, it may face challenges in maintaining the long-term sustainability of the solutions it produces [19]. The involvement of stakeholders in the design process can be time-consuming and may require significant resources. Additionally, stakeholders may have conflicting interests or priorities, which can make it difficult to arrive at a consensus on the design solution.

Issues with Scaling

Participatory Design can be challenging to scale, particularly when anonymity is required, or when computer systems are involved [2]. Maintaining anonymity can be difficult when working with small groups of stakeholders, and computer systems can make it difficult to establish trust and rapport. It is important to carefully consider the design approach when scaling Participatory Design efforts.

Context

Designing for specific user groups, such as those who are deaf, can present unique challenges in Participatory Design [20]. These challenges include finding appropriate ways to involve stakeholders who may have limited communication skills or who may not be able to participate directly in the design process. While proxies are a tool address this issue, getting information second-hand is not necessarily the ideal solution and can incur extra cost.

Certain Participatory Design methods, such as inspiration card workshops, may not be appropriate for all design projects and contexts [10]. These workshops may not be effective if the participants are not familiar with the design problem or if there is a lack of trust between the stakeholders and the designers. In addition, some participants may dominate the discussion, which can limit the input of other stakeholders.

Uncertain Future Development

As with many fields, the future development of Participatory Design is uncertain[2]. It is unclear how the field will evolve and whether it will continue to be embraced by designers and stakeholders. There is a need for ongoing research and development to ensure that Participatory Design remains relevant and effective.

Conclusion

Despite these challenges, Participatory Design has the potential to produce more innovative and effective solutions by involving relevant stakeholders in the design process[10]. Participatory Design offers a wide range of tools to facilitate stakeholder engagement and can be applied across many domains, including project management. By utilizing Participatory Design, project managers and designers can gain a better understanding of stakeholder needs, which can lead to better project outcomes.

Annotated Bibliography

Ehn, P. (2012). Participatory Design. In J. Simonsen & R. Robertson (Eds.), Routledge International Handbook of Participatory Design (pp. 1-12). New York, NY: Routledge. This handbook provides a comprehensive overview of Participatory Design, including entries from many of the field's leading researchers.

Sanders, E. B.-N., and Stappers, P. J. (2008). Co-creation and the new landscapes of design. CoDesign, 4(1), 5-18. In this article, Sanders and Stappers explore the concept of co-creation in design, arguing that it is a key aspect of Participatory Design. They discuss the benefits and challenges of co-creation and provide examples of its application in practice.

Sanders, E. B.-N., and Stappers, P. J. (2014). Probes, toolkits and prototypes: Three approaches to making in codesigning. CoDesign, 10(1), 5-14. In this article, Sanders and Stappers discuss the use of probes, toolkits, and prototypes as tools for co-designing. They argue that these tools can help to engage stakeholders in the design process and facilitate collaboration and creativity.

Project Management Institute (PMI). A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge : PMBOK Guide. 5th ed., Project Management Institute, 2013. The PMBOK guide is one of the key resources of project management best practices and provides a framework for its implementation.

Liam Bannon, Jeffrey Bardzell, and Susanne Bødker. (2018). Reimagining Participatory Design. interactions 26, 1 (January - February 2019), 26–32. This article provides an overview of Participatory Design and discusses its history, current challenges, and uncertain future.

Halskov, K., and Dalsgaard, P. (2006). Inspiration card workshops. Proceedings of the 6th Participatory Design Conference, Trento, Italy. In this article, the authors describe the use of inspiration card workshops in Participatory Design. They discuss the benefits and limitations of this method and provide examples of its use in practice.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Ehn, P. (2012). Participatory Design. In J. Simonsen & R. Robertson (Eds.), Routledge International Handbook of Participatory Design (pp. 1-12). New York, NY: Routledge.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Liam Bannon, Jeffrey Bardzell, and Susanne Bødker. (2018). Reimagining Participatory Design. interactions 26, 1 (January - February 2019), 26–32. https://doi-org.proxy.findit.cvt.dk/10.1145/3292015

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Sanders, E. B.-N., and Stappers, P. J. (2014). Probes, toolkits and prototypes: Three approaches to making in codesigning. CoDesign, 10(1), 5-14.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 Sanders, E. B.-N., and Stappers, P. J. (2008). Co-creation and the new landscapes of design. CoDesign, 4(1), 5-18.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Spinuzzi, C. (2005). The methodology of Participatory Design. Technical Communication, 52(2), 163-174.

- ↑ Bødker, K., Grønbæk, K., and Kyng, M. (1993). Cooperative design: Techniques and experiences from the Scandinavian scene.

- ↑ Grudin, J. (1990). The computer reaches out: The historical continuity of human-computer interaction. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction, 7(1), 59-68.

- ↑ Project Management Institute. A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge : PMBOK Guide. 5th ed., Project Management Institute, 2013.

- ↑ Muller, M. J., & Kuhn, S. (1993). Participatory Design. Communications of the ACM, 36(4), 24-28.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 Kim Halskov and Peter Dalsgård. 2006. Inspiration card workshops. In Proceedings of the 6th conference on Designing Interactive systems (DIS '06). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 2–11. https://doi.org/10.1145/1142405.1142409

- ↑ Clement, Andrew & Van den Besselaar, Peter. (1993). A Retrospective Look at PD Projects. Commun. ACM. 36. 29-37. 10.1145/153571.163264.

- ↑ Yamauchi, Y. (2012). Participatory Design. In: Ishida, T. (eds) Field Informatics. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi-org.proxy.findit.cvt.dk/10.1007/978-3-642-29006-0_8

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Project Management Institute. A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge : PMBOK Guide. 5th ed., Project Management Institute, 2013.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Jetter, Antonie, et al. THE PRACTICE of PROJECT MANAGEMENT in PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT: INSIGHTS from the LITERATURE and CASES in HIGH-TECH the Practice of Project Management in Product Development: Insights from the Literature and Cases in High-Tech 2. PMI, 2016, www.pmi.org/-/media/pmi/documents/public/pdf/research/practice-project-management-product-development.pdf?v=e2fa08df-bfcf-4347-b144-df2babbaf90e

- ↑ Boyd-Graber, Jordan & Nikolova, Sonya & Moffatt, Karyn & Kin, Kenrick & Lee, Joshua & Mackey, Lester & Klawe, Maria. (2006). Participatory Design with proxies: Developing a desktop-PDA system to support people with aphasia. Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems - Proceedings. 1. 151-160. 10.1145/1124772.1124797.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Jungk, R. & Müllert, N. (1987): Future Workshops: How to create desirable futures. London: Institute for Social Inventions.

- ↑ Vidal, René. (2006). "Chapter 6: The Future Workshop" Creative and Participative Problem Solving - The Art and the Science.

- ↑ Schuler, D., & Namioka, A. (Eds.). (1993). Participatory Design: Principles and Practices (1st ed.). CRC Press. https://doi.org/10.1201/9780203744338

- ↑ Karasti, H., and Baker, K. (2004). Infrastructuring for the long-term: Ecological considerations in collaborative design. Proceedings of the 2004 Participatory Design Conference, Toronto, Canada.

- ↑ Clement, A. (1994). Designing interactive systems with persons who are deaf. Interactions, 1(2), 57-63.