Porter's Five Forces Framework

Abstract

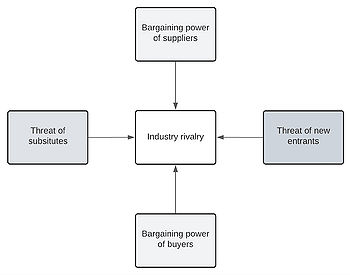

The competitive forces model, also known as Porter’s Five Forces framework, is a strategy tool used in industrial organization economics for analyzing the competition in the operating environment of a company. Porter’s Five Forces framework was published by Michael E. Porter of Harvard University in 1979 in Harvard Business Review.[1] Porter developed the model in response to the SWOT analysis - another tool for strategic decision-making - which was considered as rigor and ad hoc.[2] Porter's Five Forces framework consists of five fundamental powers that drive industry competition, namely: bargaining power of suppliers, bargaining power of buyers, threat of substitutes and complementary goods, threat of new entrants to the market, and internal market competition.[1] Three forces represent horizontal competition: threat of substitutes and complementary goods, threat of new entrants to the market, and internal market competition. Vertical competition is represented by the bargaining power of both suppliers and buyers.

The five competitive forces can be assessed to determine the profitability potential of markets and industries for a company. Analyzing Porter’s Five Forces can be of great value to companies for exploring and examining market entry opportunities with regards to expanding and evaluating project portfolios – for example, in the field of product and service development. By assessing the entry barriers of industries, managers can make strategic decisions with regards to current and future projects in the company portfolio.

This article is structured as follows: first, each of Porter’s Five Forces is explained in depth, after which the application of the forces in the context of project and portfolio management is described. Besides, limitations with regards to the competitive forces model are highlighted, and annotated bibliography for further reading is listed and briefly elaborated upon.

Contents |

Big idea

Porter’s Five Forces model is a strategic tool that can be used by strategists to determine the potential of an industry, by identifying threats and opportunities based on the evaluation of the five forces. The Five Forces model can be used alongside different types of strategic management tools such as the SWOT analysis (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, threats), balanced scorecard, OGSM (objectives, goals, strategies, measures) and the PESTEL analysis (political, economic, social, technological, environmental, legal factors), to create a complete overview of the opportunities and threats in industries or markets.

Porter’s Five Forces framework is important for managers that make strategic decisions, as it prevents a narrow view that is solely based on the core business, with regards to identifying competitive forces related to the industry.[1] Managers often only consider direct antagonists when focusing on gaining market share, such that they do not take into account that they are competing with buyers and suppliers, and that they are unaware of possible new entrants and substitute products entering the industry. Being aware of these dynamics and managing resulting risks is essential for reducing and handling the complexity of organizational initiatives.[3] Each of the forces can be analyzed and labelled as either a low, moderate or high threat to the industry in which a company operates. As a result, a clear overview of forces affecting the industry is established, on which can be acted strategically in order to exploit or explore opportunities, and defend against threats in the industry. For project and portfolio managers, this overview can help to make decisions with regards to the management of ongoing projects, and to identify a need for exploration or exploitation in the company portfolio to maintain a strong position in an industry. Program managers could use the framework to monitor external influences, which is key when considering the program’s continued alignment with the organization’s strategic goals and objectives.[4]

Threat of new entrants

Industries evolve by the entrance of new competitors in industries. Although companies are always seeking to gain market share by deploying new resources in new industries, they must first deal with market entry barriers. The threat of entry is determined by the entry barriers imposed by existing competitors in the industry. High and low entry barriers can respectively prevent or stimulate companies to enter new markets. According to Porter's publication on the five forces framework, barriers to entry are based on six major sources, namely: economies of scale, product differentiation, capital requirements, cost disadvantages independent of size, access to distribution channels, and government policy.[1] These conditions and resulting entry barriers are subject to change over time, and can also be affected by the strategic decision-making of large industry segments.[1]

- Economies of scale - Economies of scale affect entry barriers as aspirants are forced to join markets on a large scale, or must accept a major cost disadvantage which can be hard to overcome. Economies of scale also have an impact on the operations of companies, such as supply chain management and financing.[1]

- Product differentiation - Product differentiation refers to brand identification by customers, which results in customer loyalty. Entrants have to focus on winning customer loyalty from current brands in the market. Factors such as time of entry, customer service, advertising and differences in product features affect brand identification, which is often closely related to economies of scale.[1]

- Capital requirements - Capital requirements refers to the extent to which large investments are needed to enter a specific market or industry, thus limiting the number of potential – often smaller – entrants. Often, large starting capitals are needed to properly entry industries and take market share. Moreover, R&D and marketing costs are often unrecoverable in the short term after entry, meaning that they impose higher entry barriers.[1]

- Cost disadvantages - Cost disadvantages independent of size refer to the extent to which companies have cost advantages unavailable to competitors, independent of the size and present economies of scale. These cost advantages can often be enforced through patenting. Other factors that lead to independent cost disadvantages are effects of the learning curve, access to raw materials, assets purchased at pre-inflation prices, government subsidies, or favorable locations.[1]

- Access to distribution channels - Access to distribution channels refers to the extent to which companies can secure distribution of its product or service. If there are few distribution channels, and if a company has tight arrangements with regards to distribution channels, it is hard for new entrants to get in between or costly to set up new channels.[1]

- Government policy - Government policy refers to the extent in which industries are regulated or controlled in the form of license requirements, industry standards and limitations with regards to acquiring raw materials.[1]

Threat of substitutes

Substitute products refer to similar products that can replace the core product of an industry. This results in the industry product being limited with regards to its pricing, quality and thus potential of the industry. If industries are not able to differentiate or improve the quality of its product to cover the effects of the emergence of substitute products, industry earnings and growth will suffer. In the case of more attractive substitute products that are better in terms of the trade-off between performance and price relative to the industry product, the profit potential of an industry is limited. In growing markets for specific products or services, substitute products can result in the diffusion of the profitability potential, as product prices are driven down to compete. Substitute products need to be considered strategically, especially when they are produced by industries profitably, or when they are subject to trends with regards to the performance-price trade-off.[1]

Bargaining power of customers

Bargaining power of buyers refers to the ability of buyers to force down prices, demand higher quality and let competitors in the industry compete, whilst driving down industry profitability. Several characteristics of the market situation and importance of its purchases relative to the business determine the bargaining power of buyers. Buyers can be either classified as consumer groups, industrial buyers, or commercial buyers.[1]

Buyer groups are powerful in the case of high fixed production costs, which means that suppliers in the industry are dependent on large volume sales. If products offered in the industry are standardized or undifferentiated, buyers can play companies to each other as there are multiple alternative suppliers. Buyer groups are especially price sensitive when the product they buy makes up a significant fraction of the costs of the product they sell. If this is not the case, buyers will be less sensitive to price levels. In the case of buyers selling products with low profit margins, buyer power is essential. On the other hand, if the product that buyers sell is highly profitable, buyer power is less essential as overall profitability remains high. Buyer power is also important when the industry project has no impact on the quality of the goods and services that the buyer is selling. If the quality of products and services are dependent on the quality of the product of its suppliers, buyers tend to be less price sensitive. With regards to the quality of products, buyer bargaining power can be affected by the extent to which the value of an industry product can pay for itself. In the case of a buyer choosing for an industry product that – based on its quality – pays for itself in the long run, buyers are price insensitive. On the contrary, if and industry product does not guarantee paying for itself, buyers tend to be more price sensitive. Buyers can also obtain high bargaining power when integrating backwards with relation to the production of the industry’s product. If companies are not able to produce a product themselves – and thus integrating backward – buyer power could be lower.[1] Overall, consumers are less price sensitive when buying undifferentiated products that are relatively expensive compared to their income, and where quality is not of great importance. For retailers, bargaining power can be strengthened by influencing consumer purchasing decisions, thus influencing the production of products by manufacturers.[1]

Bargaining power of suppliers

Suppliers can use bargaining power on companies in industries by altering prices and quality of goods and services they provide. In order to improve the profitability of their own goods and services, they are able to intensify competition among industry competitors due to the erosion of profitability of goods and services sold downstream. Several characteristics of the market situation and importance of its purchases relative to the business determine the bargaining power of suppliers.[1]

Supplier groups are especially powerful when dominated by a small number of companies that are more concentrated than the industry the supplier group is selling to. Switching costs are another major factor that determines the power of suppliers. Switching costs refer to the lock-in of companies with regards to their existing setup of supply chains in collaboration with suppliers. Supplier power increases and decreases, if switching costs are high and low respectively. Suppliers are also considered powerful in the case of them not being obliged to compete with other products for sale to the industry, and when integrating forward into the industry. If an industry is not one of the main customer segments of a supplier, the supplier will make use of its bargaining power. On the other hand, in the case of the industry being one of the more important customer segments a supplier is selling to, suppliers will try to defend their market share by supporting their buyers in the form of pricing, R&D and lobbying.[1]

Competitive rivalry

Companies operating in an industry want to obtain the best market position. By using price competition, product diversification and other tactics, they strive to obtain the largest market share in the industry. This phenomenon is also known as “jockeying for position”.[1] The intensity of the competition in an industry is key for determining the potential for entry.

Companies in industries all have their own unique identity and vision when it comes to their strategy. This naturally leads to competition, as each company strives towards becoming the dominant party when it comes to setting direction in industries, especially in slowly growing industries. If industries consist of many competitors that have comparable sizes and power, internal competition drastically increases. This also counts for the offered products; in the case of products and services being offered that are undifferentiated and are lacking switching costs, rivalry will increase. If companies can lock in buyers, rivalry will be lower as buyers are less likely to switch to a competitor. In the case of perishable products and products that involve high fixed costs, prices are often cut among competitors in the industry. Industry competition is especially high when exit barriers are present. Exit barriers, in the form of specialized assets and loyalty towards operating in a particular field of business, lock companies into competing in an industry that has become economically unattractive. As a result, excess capacity and price-cutting disturbs the supply-demand balance in industries. As industries mature, growth rates stabilize or decline, which results in lower profitability and shakeout.[1]

Application

Project and portfolio managers should assess Porter’s Five Forces, to ensure that a clear image is formed of the industry and underlying causes of competition. After the assessment, managers can translate the identified forces into strengths and weaknesses of their company relative to the forces present in the industry. Consequently, a strategic action plan could be established that focuses on three topics: positioning the company, influencing the balance and exploiting industry change.[1]

Positioning the company

By positioning the company such that the company’s strengths and weaknesses are taken into account when making strategic moves, a company can defend itself against threats present in the industry. On the other hand, companies can also use the forces to identify weaknesses in the industry, which they can adapt to reap the benefits of these weaknesses. Thus, by the identification and assessment of the five forces present in the industry, the company can position itself such that it can minimize the negative effects of its weaknesses and maximize the impact on the industry by deploying its resources efficiently. In the context of portfolio and project management, the projects could be selected or driven by these opportunities such that the company creates as much value as possible – both in the form of exploiting opportunities and defense against industry threats.[1]

Influencing the balance

Next to using the strengths and weaknesses of a company relative to the industry, a company can also choose to affect the underlying causes of the present industry forces. By not only dealing with the outcomes of the forces, but also with their root causes, companies can alter the industry balance with regards to the five forces. Project and portfolio managers should be aware that the projects that they are undertaking on a strategic level are thus not only dealing with the present threats, but are preferably also altering the force balance in the industry.[1]

Exploiting industry change

Over time, industries tend to change: growth rates do not remain stable, and product differentiation often declines as markets mature. Moreover, companies are integrating vertically in order to improve profitability. These trends should also be taken into account when formulating a strategy. It is critical to evaluate and anticipate industry changes, and to derive which impacts these changes could potentially have on the current forces present in the industry. Porter’s Five Forces framework can be used not only for the analysis of competition, but also for long-range planning in order to predict the eventual profitability of an industry. By examining each force, estimating its future magnitude and underlying cause, the profitability potential of an industry can be estimated. The potential of this industry is dependent on the ultimate power present in the industry; future entry barriers to entry, the industry position relative to potential future substitutes, future intensity of competition, and future bargaining power of buyers and suppliers.[1]

The framework can help to set up a diversification strategy, which is interesting for companies who are managing portfolios of potential new products or services. Moreover, based on the five forces, key characteristics of the industry can be determined in the form of economies of scale, brand identity, overhead costs, experience curves and capital costs required to compete. In other words, it provides a roadmap to determine the complex issue of determining the future value - or potential – of a business.[1]

Not only the five forces should be considered when formulating a strategy. As mentioned earlier, the analysis could be complemented by other tools for strategic analysis such as a SWOT analysis, balanced scorecard, OGSM and the PESTEL analysis. Moreover, different factors should be taken into account that are not considered as forces, but are key to the dynamics of forces within a competitive industry, such as: industry growth rate, technology and innovation, governmental forces, and complementary goods and services. Creating awareness of the complete environment, including technical, political, market and economic aspects, is key to to the success of projects.[5]

Limitations

Despite the usefulness of Porter’s framework to explore the potential value of industries and its entry barriers, it has some major limitations according to academics and strategists. Analyzing the real world and modeling it as a system whilst evaluating multidimensional aspects/criteria is key to mastering project management in engineering and management.[6] However, assumptions that have been made on which the model is based can be contested.[7] First of all, Porter’s Five Forces framework assumes that buyers, competitors and suppliers are separate forces that are not interacting or conspiring. This is of course not the case in real life, as these forces do interact, which could have major impact on industries. Secondly, it is assumed that structural advantage is the main source of value according to the framework – in the form of entry barriers. However, in strategic decisions, entry barriers are just a part of the value that is formed. Finally, it is assumed that participants are able to respond to all changes in the market timely, and that uncertainty is low. In practice, this is not the case in most industries, as flexibility is often demanded throughout the development of markets and industries. Moreover, it is hard to evaluate the potential of an industry, without properly taking into account the resources that a firm has relative to the industry. This so-called resource-based view could help to add a crucial dimension to the framework.[8] In other words, the model places too much weight on the macro-environment, and does not take into account all major factors that could influence industry potential.[9]

Next to the limitations that are based on the underlying assumptions of the model, another problem arises. Porter’s Five Forces model includes five forces, which can be questioned, as it could be the case that more forces exist in the context of industry competition. Several academics and strategists have insisted on adding a sixth force. Suggestions for a sixth forces to include are complementors[10] – based on the idea of game theory – and a governmental force that also includes pressure groups. Porter has rejected all these additions, as they should be considered as “factors” that affect the Five Forces Model.[11]

A final criticism is that the framework does not provide any solutions or directions for the identified industry potential. The model could have been more useful if clear directions were given on how to deal with identified threats in the industry.[9]

Annotated bibliography

Porter, M.E. (1979). How Competitive Forces Shape Strategy. Harvard Business Review 57(2), 137–145.[1]

This publication is the original version of the publication of Porter’s Five Forces my Michael E. Porter in Harvard Business Review in 1979. This reading can be accessed for more details on each of the forces and the establishment and application of the framework to strategic decision-making. In the article, Porter first discusses how the framework was established in the context of strategy formulation. Next, each of the five forces: threat of new entrants, bargaining power of suppliers, bargaining power of buyers, internal rivalry among industry competitors, and threat of substitution are discussed in detail. Finally, directions for the application of the framework are given.

Grundy, T. (2006). Rethinking and reinventing Michael Porter's five forces model. Strategic Change. 15(5), 213–229.[9]

This publication is all about rethinking and reinventing the Five Forces Model of Michael Porter. This reading can be accessed for more details about limitations of Porter’s Five Forces framework: it provides insights with regards to mapping competitive forces; understanding dynamics; prioritizing forces; macro analysis of sub-drivers of the forces and exploring key interdependencies. The interdependencies that are explored provides insights in how the forces can affect eachother. The article provides clear examples and illustrations of underlying micro forces that could affect each of the five forces in the framework. Macro-level forces resulting from the five forces are also highlighted and elaborated upon.

Coyne, K.P. & Subramaniam, S. (1996). Bringing Discipline to Strategy. McKinsey Quarterly 33(4), 14–25.[7]

This publication is all about restructuring strategy analysis tools, of which plenty exist. One of the analysis tools that is analyzed is the Five Forces Model of Michael Porter. The reasons for why strategy frameworks are often not suitable for all strategic decisions is elaborated upon, as each strategic decision is complex and unique. The article highlights that traditional strategy makes three assumptions: industries consist of unrelated forces, structural advantage is the only source of value, and that uncertainty is considered low, such that predictions can be made with regards to other participants’ behavior. A new and broader approach to strategy is formulated in this article, which involves additional bases for competitive advantage, alternative forms of industry structure, and taking into account varying levels of uncertainty. Moreover, implications of a new framework for strategy development are considered, and it is highlighted how the strategic posture of a firm, sources of competitive advantage, business concepts and value delivery systems affect the overall strategic direction of a company.

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 1.22 1.23 1.24 1.25 Porter, M.E. (1979). How Competitive Forces Shape Strategy. Harvard Business Review 57(2), 137–145.

- ↑ Porter, M.E, Argyres, N., & McGahan, A. M. (2002). An Interview with Michael Porter. The Academy of Management Executive (1993-2005), 16(2), 43–52. https://doi.org/10.5465/ame.2002.7173495

- ↑ Project Management Institute (2019). The Standard for Risk Management in Portfolios, Programs, and Projects.

- ↑ Project Management Institute (2017). The Standard for Program Management (4th ed.).

- ↑ Project Management Institute, Inc. (2021). A guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (Pmbok guide) and the standard for Project Management.

- ↑ Züst Rainer, & Troxler, P. (2006). No more muddling through mastering complex projects in engineering and management. Springer.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Coyne, K.P. & Subramaniam, S. (1996). Bringing Discipline to Strategy. McKinsey Quarterly 33(4), 14–25.

- ↑ Wernerfelt, B. (1984). A Resource-based View of the Firm. Strategic Management Journal, 5(2), 171–180. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250050207

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Grundy, T. (2006). Rethinking and reinventing Michael Porter's five forces model. Strategic Change. 15(5), 213–229. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsc.764

- ↑ Brandenburger, A. M. & Nalebuff, B.J. (1995). The Right Game: Use Game Theory to Shape Strategy. Harvard Business Review, 73(4), 57–71.

- ↑ Porter, M.E. (2008). The Five Competitive Forces that Shape Strategy. Harvard Business Review, 88(1), 78–93.