Project Quality Management

Developed by Sveinn Isleifsson

Quality processes should be used on all types of projects. As part of the Project Triangle, project should be completed within time and cost, while maintaining high quality. It is important for the successful outcome of the project. Worldwide competition has also resulted in a stronger emphasis on quality. If quality requirements are not met, it could lead to negative impact to both the customer and the company building the product or providing the service. The approach used to ensure quality can differ a lot between projects. For example, when developing a software there are other procedures than when developing a drug. To ensure quality satisfaction for the customer some Quality Management processes must be implemented. The quality management system consist of quality planning, quality assurance, and quality control. In this article we will look at how quality is defined and what are the best practices for managing quality to satisfy the customer and to meet quality standards.

Contents |

What is quality?

There is no single definition of quality, depending on who is asked quality can mean different things. The ISO definition for quality is “The quality of an organisations’ products and services is determined by the ability to satisfy customers and the intended and unintended impact on relevant interested parties.” and “ The quality of products and services includes not only their intended function and performance, but also their perceived value and benefit to the customer”[1]. Quality can also mean[2]:

- Relative quality - the product or service compared to other products or services.

- Fitness for use - the product or service is able to be used.

- Fitness for purpose - the product or service will meet its intended purpose.

- Meets requirements - the product or service in relation to the customer’s requirements.

- Quality is inherent - quality cannot be tested in. The process must support designing in quality, not attempting to test it in at the end of the process.

The lack of definition on this term causes troubles for the project manager, if they cannot describe precisely what quality improvements they are aiming for, it will be difficult to implement quality improvement objectives.

| Manufacturing | Service | |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Product-based, a precise and measurable set of characteristics | Based on stakeholders’ expectations and perceptions |

| Attributes | Performance, conformance features, reliability, durability, serviceability, perceived quality and aesthetics | Access, communication, competence courtesy, credibility reliability responsiveness, security, tangibles, understanding/knowing the customer |

Dimensions of quality for manufactured products:

- Performance - The basic operating characteristics of the product.

- Features - The “extra” items added to the basic features.

- Reliability - The probability that a product will operate properly within an expected time frame.

- Conformance - The degree to which a product meets pre established standards.

- Durability - How long is the product life span.

- Serviceability - The ease/speed of getting repairs.

- Aesthetics - How a product looks, feels, sounds, smells, or tastes.

- Safety - Assurance that the customer will not suffer injury or harm from a product.

Dimensions of quality for service:

Quality in service is directly related to time and the interaction between employees and the customer. Evans and Lindsay identify the following dimension of service quality:[4]

- Time and timeliness - How long must a customer wait for service, and is it completed on time?

- Completeness - Is everything the customer asked for provided?

- Courtesy - How are customers treated by employees

- Consistency - Is the same level of service provided to each customer each time?

- Accessibility and convenience - How easy is it to obtain the service?

- Accuracy - Is the service performed right the first time?

- Responsiveness - How well does the company react to unusual situations, which can happen frequently in a service company?

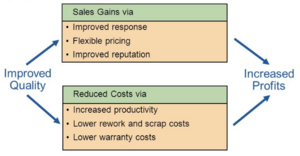

Why is quality important?

Achieving quality is a demanding task. It requires active participation from all levels within the organisation, understanding of the principles of quality, and engaging employees in the necessary activities to implement quality. Improving quality will benefit organisations increasing sales and reducing costs, both of which can increase profitability. Furthermore, improved quality allows costs to drop as the company increase productivity and lower rework, scrap and warranty costs[5]. When these things are done well, the project will more often than not, satisfy its customers and obtain a competitive advantage.

Other potential key benefits are[1]:

- Increased customer value

- Increased customer satisfaction

- Improved customer loyalty

- Enhanced repeat business

- Enhanced reputation of the organisation

- Expand customer base

- Increased revenue and market share

Customer Focus

The primary focus of quality management is the customer. Since the organisation depends on the customer, they should understand future needs as well as current ones. The reason is simple, customers who are happy and delighted are less likely to switch to a competitor, which eventually translates into profit [6]. There are different approaches and techniques to achieving business excellence, to name a few; Total Quality Control, Quality Management, TQM, Process Improvement, Six Sigma, Business Process Management (BPM), Lean, Baldrige. They all have some common elements that are the keys to success. The most important element of quality is the customer. Therefore, products and services must be designed to meet customer expectations and needs for quality and try to exceed their expectations where possible[6]. Organisations attain customer focus when all people in the organisation know what the customer requirements must be met to ensure all internal and external stakeholders are satisfied. All quality improvements should ultimately target improving the customer satisfaction. For this, the organisation can conduct surveys and feedback forums for gathering customer satisfaction and feedback information[7].

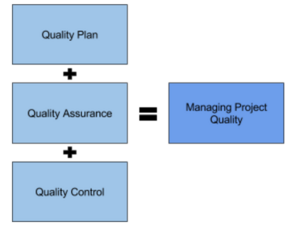

Managing project quality

The Quality Management processes implement the quality management system through the procedures and processes of quality planning, quality assurance, and quality control. This is a continuous process, improvement activities using quality techniques and tools throughout the project life cycle. If the requirements for the product of the project are consistent with real or perceived needs of the customer, then the customer is likely to be satisfied[2].

The quality plan defines the quality standards the project must meet, and how you will manage the compliance of deliverables. This requires agreeing with project sponsor and other stakeholders regarding objectives and standards to be achieved. In this step, tools are established and necessary resources are determined to achieve quality standards.

Project quality assurance activities are an important aspect of building in quality rather than trying to test in quality at the end of the development life cycle. Quality assurance focus point is on continuous improvements of the process, reducing waste, allowing processes to operate at increased levels of efficiency[2]. During the quality assurance phase the project manager must ensure that objectives and standards to be achieved are communicated, understood and accepted by all appropriate stakeholders[1].

Performing quality control is where the monitoring and controlling of the project is required, to ensure the project adhere to relevant quality standards. This process should be used during the whole project life cycle to analyse unsatisfactory performance and find preventive actions. There are several methods for managing quality control using tools such as[8]:

- A cause and effect diagram: Identifies possible causes for an effect or a problem and sorts ideas into useful categories.

- Control Charts: Graphs used to study how a process changes over time. This approach is used when monitoring and tracking repetitive activities such as: cost, variances and volumes.

- Pareto Charts: Used when there are many problems or causes, to focus on which factors are the most significant.

- Inspections: Examines the project’s artifacts to determine conformance to standards and validate defect repairs.

There can be some confusion regarding quality assurance and quality control. The difference between those two is that quality assurance is part of the executing process and is concerned with making sure that objectives are followed. This process focus on continuous process improvement, which is an iterative means for improving the quality of all processes[9].

Continuous improvements

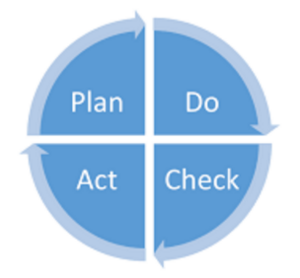

The Deming Wheel is a four-stage process for continuous quality improvement. It is also known as Plan-Do-Check-Act cycle (PDCA), and is a four-step management method used for continuous quality improvement of processes and products. This method complements with Deming’s 14 points and are the foundation for today's quality management systems employeed by many successful organisations[6].

Implementation/Application

Coordinating continuous improvement projects with a PDCA cycle involves these four steps:

- Plan

- Understanding the existing situation and study the process, identify the problem, collect data, set goal necessary to deliver results, and develop the plan for improvement. When analysing the current state, techniques such as 5 Whys or Ishikawa diagram can be used to help identifying the root cause.

- Do

- Implement the plan on a test basis and implement the solution, measure improvement.

- Check

- Assess the plan, measure and confirm the results with comparison of previous phase and expected targets, in order to identify adjustments. Ask question such as; is it working? are goals achieved? Look for deviation from the plan in implementation and also look for the appropriateness and completeness of the plan to enable the execution. Collect data.

- Act

- Institutionalise improvement, document the solution and standardize. If the results were not successful, observe and learn what can be done better and adjust before starting the cycle again.

The PDCA cycle is a continuous feedback loop to analyze, measure, and identify sources of variations from customer requirements and take corrective action. The steps are designed to be used as a dynamic model, and completion of one turn of the cycle flows into the beginning of a new cycle again. Usually, it needs to go through multiple iterations of phases (PDC-PDC-PDCA) within the same cycle, before the desired results can be accomplished[10].

The model is both widely applicable and its simplicity is something that makes it so relevant. It is particularly useful as a focal point for continuous improvements, as it can be implemented in all types of projects. The PDCA method emphasizes on documentation and standardization for achieved improvements and enhance the learning process for teams or individuals.

Limitations

There are many advantages and benefits affiliated with using PDCA cycle as a method to achieve continuous improvements. Despite these benefits there are also limitations that should be taken into consideration. Deming was cautious over the use of the ‘PDCA’ terminology and warned it referred to an explicitly different process, referring to a quality control circle for dealing with faults within a system, rather than the PDCA process, which was intended for iterative learning and improvement of a product or a process[11]. The difference between “Do” and “Act” can be confusing as they have the same meaning in English. The correct word for “Act” is actually “improve” [12]. Another limitation of the method is that it does not deal with the human side. Continuous improvement requires continuous change, so the people have to keep pace to changed practices and adjust to new procedures. A problem with the way the “plan“ phase is performed, is that companies go very quick into the root-cause discussion, and consequently quickly come up with solutions. Despite that speed is positive, it often means that they do not analyze the problem properly and the solutions therefore may be “quick fixes” rather than more permanent good solutions. Frequently, only one alternative is really examined, and a real evaluation of alternatives does therefore not take place [10].

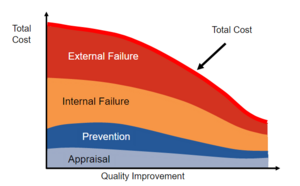

Cost of quality

Cost of quality is a concept that is often overlooked when planning the quality effort in a project. The term is used to reflect the total price of all efforts to achieve quality in a product or service. Key project decisions that impact the cost of quality come from either striving for “zero” defects—how much it will cost the project to achieve this high level of quality, versus achieving “good enough” quality—which may result in costly product recall or warranty claims[13].

The cost of achieving good quality

- Prevention costs

- These are planned costs an organisation incurs to ensure that errors are not made at any stage during the delivery process of that product or service to a customer. The delivery process may include design, development, production, and shipping. Examples of prevention costs include quality planning cost, quality administration staff costs, process control costs, market research costs, field testing costs, and preventive maintenance costs.

- Appraisal costs

- These include the costs of verifying, checking, or evaluating a product or service during the delivery process. Examples of appraisal costs include receiving or incoming inspection costs, internal production audit costs, test and inspection costs, instrument maintenance costs, process measurement and control costs, supplier evaluation costs, and audit report costs.

The cost of poor quality

The cost of poor quality is the difference between what it actually costs to produce a product or deliver a service and what is would cost if there were no defects[6]. These cost incurs because the product or service did not meet the requirements and had to be fixed or replaced, or the service had to be repeated. Failure costs can be further subdivided into two groups: internal and external failures[14].

- Internal failures

- Internal failures include all costs resulting from the failure found before the product or service reaches the customer. Example of internal failure includes, scrap and rework costs, downgrading costs, repair costs, and corrective action costs from nonconforming product or service.

- External failure

- External failure occur when the customer finds the failure. External failure costs do not include any of the customer´s personal costs. Examples of these failure costs include warranty claim costs, customer complaint costs, product liability costs, recall costs, shipping costs, and customer follow-up costs.

The costs of preventing mistakes are always much less than the costs of inspection and correction. The impact of quality investments on profits cannot always be directly assessed because it usually is long-term. Many other variables (price, distribution, competition, effectiveness, image and publicity) influence profits, and simply spending on quality does not automatically lead to profits because the strategy and functionality of the investment are also important[13].

Conclusion

Planning quality activities will ensure a high degree of project and product success, which will lead to a high return on investment for the effort invested in the project. Continuous improvement efforts are cross-functional in nature, so as long as a project has defined objectives and deliverables, there should be a project quality plan to measure the delivery and process quality. Quality improvements require active participation and approval from management. A total commitment to quality is necessary throughout an organisation to successfully improve and manage project quality. Employees must be active participants in the quality improvement process and must feel a responsibility for quality.

Annotated Bibliography

For further reading related to quality management:

Books:

Tague, Nancy R (2005), “The quality toolbox”, ASQ Quality Press, Milwaukee USA. ISBN 978-0-87389-639-9

- The Quality Toolbox is a comprehensive reference to quality methods and techniques. This book is considered one of the classics, and is recommended for anyone interested in Quality Management. There are tools included for generating and organising ideas, evaluating ideas, analysing processes, determining root causes, planning, and basic data-handling and statistics. This edition liberally uses icons with each tool description to reinforce for the reader what kind of tool it is and where it is used within the improvement process[15].

Juran, J. M., and Joseph A. Feo (2010), “Juran's quality handbook: the complete guide to performance excellence”, McGraw Hill, New York USA. ISBN 978-0-07162-973-7

- Juran is one of the greatest contributors in quality management. He developed the quality trilogy, quality planning, quality improvement and quality control[16]. This book provides comprehensive coverage of quality management: fundamentals of managing for quality, the managerial role in attaining quality, implementing and deploying quality, the managerial tools, the statistical tools, the roadmap to attain quality leadership[17].

Deming, W E. (2013), “The essential Deming : leadership principles from the father of quality”, McGraw-Hill, New York USA. ISBN 978-0-07179-022-2

- The book is a wealth of articles, papers, lectures, and notes on a wide range of topics, but the focus is on Deming’s main message: quality and operations are all about systems, not individual performance, the system has to be designed so that the worker can perform well[18].

Web-pages:

ASP.org, American Society for Quality web page

- It is a quality community with individuals and organisations worldwide. There you can find useful; publications, books, magazines and research papers.

Reference

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 ISO9000, 2015, Quality management systems - Fundamentals and vocabulary. International Organization for Standardization.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Paul Dinsmore (2011). The AMA handbook of project management’’. 3th edition, 123-139. New York. ISBN 978-0-8144-1542-9.

- ↑ Harvey Maylor (2010). Project management. 4th edition, 200-215. Harlow, England NY. ISBN 9780273704324.

- ↑ J.R. Evans and W.M Lindsay (1995). The management and control of quality. 3th edition, South-Western College Pub. ISBN 78-0-314-06215-4.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Jay Heizer (2014). Operations management : sustainability and supply chain management’’. 11th edition, 241-270. Essex. ISBN 0273787071.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Roberta Russell (2011). Operations management : creating value along the supply chain’’. 7th edition, 61-99. Hoboken, N.J. Chichester. ISBN 9780470646236.

- ↑ Total Quality Management (TQM)”. [online] tutorialspoint.com. Available at: https://www.tutorialspoint.com/management_concepts/total_quality_management.htm [Accessed 16 Sep. 2016].

- ↑ Schulmeyer, G. Gordon & McManus, James I. (1996). Handbook of software quality assurance’’. 2th edition. Boston. ISBN 978-1-59693-186-2.

- ↑ Paul Newton (2015). ‘’Project Management Processes’’. ISBN 978-1-62620-959-6.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Lodgaard E., Aasland K. (2011). An examination of the application of Plan-Do-Check-Act cycle in product development’. Norwegian University of Science and Technology.

- ↑ Moen R, Norman C. (2010). Circling back: clearing up the myths about the Deming cycle and seeing how it keeps evolving’. Qual Progress.

- ↑ N Nayab (2013). Exploring the Disadvantages of PDCA Methodologies. [online] brighthubpm.com. Available at: http://www.brighthubpm.com/methods-strategies/75929-exploring-the-disadvantages-of-pdca-methodologies/[Accessed 15 Sep. 2016].

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Valarie, Zeithaml, Berry & Parasuraman (1996). The Behavioral Consequences of Service Quality’’. The Journal of Marketing, 60(2), 31-46

- ↑ Timothy Kloppenborg (2002). Managing project quality’’. Vienna, Va. ISBN 978-1567261417.

- ↑ American society for quality (n.d.). The Quality Toolbox, Second Edition. [online] asp.org. Available at: http://asq.org/quality-press/display-item/?item=H1224 [Accessed 20 Sep. 2016].

- ↑ Anderson, Chris (n.d.). Who Are the Top Quality Gurus?. [online] bizmanualz.com. Available at: https://www.bizmanualz.com/improve-quality/who-are-the-top-quality-gurus.html [Accessed 18 Sep. 2016].

- ↑ American society for quality (n.d.). Juran's Quality Handbook, Sixth Edition. [online] asp.org. Available at: http://asq.org/quality-press/display-item/?item=P1397&utm_source=blog&utm_medium=link&utm_campaign=communications_blog_1397 [Accessed 20 Sep. 2016].

- ↑ American society for quality (2015). Top 8 Books Every Quality Professional Should Read. [online] asp.org. Available at: http://asq.org/blog/2015/01/top-8-books-every-quality-professional-should-read/ [Accessed 18 Sep. 2016].