Reflective practice

Written by Teis Johannesen

Contents |

Introduction

Reflective practice is the skill of being able to monitor and evaluate one’s own behaviour and practice critically as a learning experience. By distancing oneself towards one’s own performance an increased awareness of relevancy and scope is gained. This knowledge is important as real-life situations are often messy and uninterpretable at first glance, which makes the application of systematic approaches challenging. By being in constant conversation with the context, one’s past experiences and behaviour a deeper understanding can be achieved and theories become applicable. Therefore it’s a crucial competence to any professional dealing with high levels of complexity or uncertainty.

By utilizing reflective practice, one moves from otherwise inexplainable professional artistry to repeatable, developable rationale. This is achieved by utilizing a constant cycle of experimentation and reflection. While drawing upon the present and past situations solutions and decisions unique to the experienced context, can be created. Through this kind of active inquiry, the professional will then move tacit knowledge, otherwise indescribable, towards conscious thought processes.

Preface

While being an important skill for every position, like mentioned, it’s most critical in situations of high uncertainty. Traditionally developed and used in medical science and arts it's fundamentally applicable to any position where the context provides complexity beyond systematic approaches. The article will use the term designer in a broader sense, referring to a creator. This creation could be that of a system, a product, a medical procedure, a plan or simply knowledge or understanding.

This article will cover the fundamental theory of reflective practice and its terminology, its application, its history and its limitations. Recommended reads on further research on the subject will also be presented towards the end.

Theory

Reflective practice refers to the idea of conversating with the problem faced, its context, past experiences and oneself when designing. It’s based on the axiom that experiences alone do not necessarily lead to learning. That a deliberate reflective process is essential for continuous learning.

By utilizing reflective practice one effectively ensures the learning in Learning-by-doing, an educational theory popularized and expanded by the likes of John Dewey and Richard DuFour.

Within the theory of reflective practice lies terminology essential for understanding, application and communication. The most fundamental of which will be elaborated in the coming sections.

Professional artistry

Professional artistry is the display of immediate understanding and response from a professional when faced with a challenge in practice. What differs professional artistry from the usual systemic approach that we all perform every day, is its high level of autonomy. The use of professional artistry shown by professionals deeply invested in their field can sometimes be unconscious. A somewhat deeper integrated connection within the thought processes. Like riding a bicycle, the act may be explained in detail, but its execution requires very little conscious thinking. This artistry is enabled by what is often referred to as embodied or tacit knowledge[2].

Reflection-in/on-action

Like a conversation, any interaction with a complex system, like a person, is to some extent unpredictable. In the same sense, reflective practice aims to tackle high uncertainty situations with a constant shift between experimentation and investigation. But as with language, that which is communicated conveys more than its factuality. It conveys contextual information like rules, culture, history and expression. With the knowledge of this context, we are able to decipher and shape our next inquiry. Comparing what is observed with previous experiences or collectively accumulated knowledge taught through education, we are able to steer the direction of exploration. Through reflection either in the faced situation or after, the professional can abstract her findings, compare with her repertoire of knowledge and compose an answer to this unique problem. [4]

Worldmaking

The act of worldmaking is to create or frame a virtual world in which the context, problems and goals of a given situation live. It is to create an existence on relevance, to determine the scope of intervention. To be able to tackle high complexity, It is essential for any practitioner to distinguish subjects of high importance from those of irrelevance. There are multiple approaches to worldmaking, many of which are described in Nelson Goodman’s book ‘’Ways of Worldmaking’’.[6] But common for these worlds is that they should be a tool in which a future could be imagined. Like a doctor, determining that symptoms and an irregular sleep schedule support a likely hypothesis from which he can fabricate a treatment, while the mental state and eating habits of the patient provide no further insight. In teams, especially multidisciplinary ones, worldmaking becomes instrumental in aligning and communicating desired outcomes, interventions and approaches. It determines common terminology and draws upon the collective knowledge of its members.

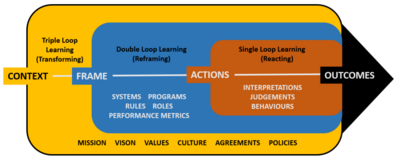

Single-, Double- and Triple-loop learning

While reflection is the main objective, not every kind of reflection have the same impact. This is why we separate our reflections into N-looped learnings. With single- and double-loop learnings being presented in the early ‘90s, by authors like Donald Schön and Chris Argyris, zero- and triple-loop learning was theorized later by various sources.[8]

- Zero-loop learnings regards itself to situations where the designer has no reflections or learnings in conjunction with an action. While being rare it's primarily seen within unconscious autonomous actions in everyday lives.

- Single-loop learnings is the act of self-correction. A prompt or concern leads to the correction of a previous action. This is where the practitioner or organisation ask themselves Are we doing things right?.

- Double-loop learnings is dealing with self-awareness. By questioning things like goals, procedures and underlying causes we ask ourselves Are we doing the right things?.

- Triple-loop learnings is where we question the underlying mechanics. On what basis do we evaluate, what is the ultimate goal and how do we fundamentally develop ourselves? We ask ourselves the question How do we decide what is right?

As an example a doctor might go through reflections at these levels of learning, after an unsuccessful operation, like so:

- What did I do wrong?

- Was an operation the right treatment?

- Was I looking at the wrong symptoms when deciding this treatment?

Examples of application

While the fundamental mechanisms of reflective practice are independent of the context in which it is being used, its application might be very different depending on the domain. Here the two common roles of a designer(creator) and a project manager will be utilized to provide examples of differences. Each theme of examples will elevate the loop of learning achieved.

Feedback

If feedback and critique, whether it’s explicit or not, are not being acknowledged a practitioner might find it hard to reach desired performance and can find themselves in a standstill of improvement. While reflections on feedback might spark looped learning on multiple levels, examples of single-loop could be: A designer gets increasing feedback that his designed artefact is not being used the intended way. A manager on the other hand observes that his department, responsible for implementation, struggles while those with development does not.

To accommodate the feedback, the designer could ask himself: Can my users help me design the intended use? and the manager: Should my implementation-specialist be part of development departments?. With the practitioners questioning previous choices and how they can be changed to suit new development, they engage in a Single-loop learning.

Bias

The consequences of an unknown bias can take many forms. Like a designer missing key characteristics in the target group, as he is not a part of it. Or a manager of product development, with his technical background, neglecting marketing resulting in poor public awareness.

Instead, the creator could’ve asked himself Can I relate my target audience to myself? and the manager Is my knowledge making me favour a specific department?. By doing so they spark a reflection on their position, therefore participating in a Double-loop learning.

Approach

By not being critical of our approaches we can often find ourselves repeating mistakes unaware of their origin. As a creator, this could be observed as stagnation in innovation, as the performance indicator reaches its limit, but the situation still is considered unsuccessful. A manager might encounter a situation wherein a new department, team members unexpectedly can’t cooperate even though a previously successful organisational structure is used.

The questions the practitioners could ask themselves is then, respectively: Is the performance indicator (still) representative of success? and Is the proven organisational structure able to be transferred between departments?. By reflecting upon their goal-setting and their understanding of successful practices they engage in Triple-loop learning.

History

While the term ‘’reflective practice’’ is relatively new, it is built upon theories and ideas dating long before the ’70-’80s, when it was popularized. Donald Schön refers to Meno, a Socratic dialogue between Plato and Socrates, that touches upon the mysteries associated with searching for something one does not know what is.[1][9] Similarly it’s argued that the ability to develop logic through inquiry of the unknown, is an inherent part of being human. What has allowed us to develop beyond other species is the competence to imagine future scenarios of change. It has allowed us to prepare for winters, establish social structures and develop systems of inventions. Furthermore, it is argued that our inquiry will always be based on logic determined and stated by the people before us as it is deeply integrated into our cultural upbringing. [4]

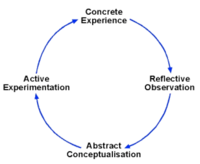

The idea of cycled experiential learning, like that presented by D. A. Kolb and R. E. Fry, and later expanded upon by G. Gibbs, gives the theory of obtaining knowledge through reflection a systematic approach.[3] [10] By presenting stages of experimentation, observation, reflection and application its users were now able to accurately and systematically describe their thought-process in situations of exploration.

As reflective practice refers to an epistemology, most research and literature is based around the education of practitioners and their organisations. Most notably is Donald Scöns studies documented in his trilogy of books regarding the ‘’reflective practitioner’’.[11][1][12] In this book series he tackles the implications of educating practitioners to tackle complex real-life practices. This is done in direct response to the systematic and sterile theories and approaches, while being based on science, falls short of the complexity of situations met in a professional context. In the series, Schön draws parallels to the traditional methodology of teaching art like architecture and musical performance.

Being in constant conversation with the context becomes the centrepiece in the model and approach of Hunter-gathering[13][14] developed and expanded through the early-mid 2010s. These theories expand the landscape of reflective practice by contributing with models portraying an exploration of the unknown as being an iterative rapid development process. Through probing the current understanding and using its outcome to form decisions of the next move, the traditional idea of developing towards a predetermined goal is abandoned. Instead, the designer(s) focus on their understanding of success.

Limitations

While reflective practice is an instrumental tool for life-long learning, it is not without its limitations. An uncritical utilization of the approach does not naturally lead to an advancement in practice or the development of better solutions. Generally, reflective practice lends itself to the capabilities of the designer. This requires either the professional to be well-informed about the domain in which he presents himself, self-critical towards his own prejudice or portray only small derivations from his observations.

When the designer lack knowledge about the context he’s presented with, he must invent his own understanding of its mechanics. In this situation, he has very little existing knowledge to draw upon. This has the potential to present different challenges for the designer. Without an understanding, he has no point of reference, whether it’s used to compare and evaluate or in planning what to focus on. He also doesn’t draw upon the accumulated knowledge generated among like-minded professionals. Tested theories, approaches and standards are potentially left behind. While a lacking pre-understanding isn’t purely negative, as it incites innovation, it can have great consequences in fields of high technicality, like medicine or construction.

Without a self-critical approach to one’s reflections, reflective practice might lead to self-indulging and strengthening of biases. Without self-doubt, the approach can lead to a less communicative process of rationalizing existing behaviour or practice. Similarly, without being critical of context the professional might herself to what can be immediately changed and disregarding the system or culture that lead up to this point.[15] In extension, without an awareness of one's capabilities of this introspective judgement, we might falsely come to the conclusion that we are void of bias. By overestimating the basis on which we judge ourselves, by comparing ourselves to known experiences of bias, we often neglect that the limitations of the experiences are biases in their very nature. Lastly, we tend to deny bias as we perceive our own intentions to be, for example, right, objective or altruistic.[16]

Lastly, compared to systematic applications of science it is time consuming. It incites introspective reflection that, if used self-critically, questions one’s own approaches. In time-sensitive situations like that often met by a fireman or doctor, this might have crucial consequences. This is why a systematic and rigorous application of tested theory is still taught in many fields. By leaning on years of dedicated research, the professional can tackle common situations with low uncertainty, with little reliance on the designers own capabilities[15]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Schön, D., 1987. Educating the reflective practitioner: Toward a new design for teaching and learning in the professions. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass A Wiley Imprint.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Schrijver, L., 2021. The Tacit Dimension: Architecture Knowledge and Scientific Research. Leuven: Leuven University Press.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Kolb, D. and Fry, R., 1975. Toward an Applied Theory of Experiential Learning. In: C. Cooper, ed., Theories of Group Processes. Ann Arbor: Wiley. (1975)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Dewey, J., 1938. Logic, The Theory of Inquiry. New York: Henry Holt and Company.

- ↑ Kaufman, S., Elliot, M. and Schmueli, D., 2003. Frames, Framing and Reframing. Beyond Intractability,.

- ↑ Goodman, N., 1978. Ways of worldmaking. Indianapolis,: Hackett Pub. Co.

- ↑ TOOL | Single, Double and Triple Loop Learning, Tamarack Institute

- ↑ Argyris, C., 1977. Double loop learning in organizations. Harvard Business Review,.

- ↑ Lacey, A., 1960. Protagoras and Meno, Plato. Trans. W. K. C. Guthrie. (The Penguin Classics, 1956. Pp. 157. Price 2S. 6d.). Philosophy, 35(135).

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Gibbs, G., 1988. Learning by Doing, A Guide to Teaching and Learning Methods. Oxford: Wheatley.

- ↑ Schön, D., 1983. The Reflective Practioner: How Professionals think in action. New York: Ashgate Publishing.

- ↑ Schön, D., 1991. The Reflective turn: Case studies in and on educational practice. New York: Teachers College Press.

- ↑ Steinert, M. and Leifer, L., 2012. 'Finding One's Way': Re-Discovering a Hunter-Gatherer Model based on Wayfaring. International Journal of Engineering Education, 28(2).

- ↑ Leikanger, K., Balters, S. and Steinert, M., 2016. Introducing the Wayfaring Approach for the Development of Human Experiments in Interaction Design and Engineering Design Science. In: International Design Conference.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Finlay, Linda (2008). Reflecting on ‘Reflective practice’. Practice-based Professional Learning Paper 52, The Open University.

- ↑ Pronin, E. and Kugler, M., 2007. Valuing thoughts, ignoring behavior: The introspection illusion as a source of the bias blind spot. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 43(4).

Reads

Frame Innovation: Create New Thinking by Design, K. Dorst. (2015) This book by Kees Dorst provides further insights into the methodology of frame creation in design practices. It deals itself with the theory both in a solo- and team context.

The role of reflection in single and double loop learning, J. Greenwood. (1998) This article, written by Professor of Nursing Jennifer Greenwood, provides a deeper explanation of the research within looped learning. It creates an overview of the complementary development and differences across authors.