Situational mapping

Created and edited by S154259 9 May 2023 (CEST)

Contents |

Abstract

Whenever a project, program or portfolio is conducted it is oftentimes with the intention of changing the status quo of the current situation. It is therefore not so irrelevant to know what the situation is and what impact the offered change (a so-called translation) in the status quo will have on the situation. Any given situation consists (for the most parts) of the same elements; human and non-human, material and symbolic/discursive elements as framed by those in it and the analyst [1] The "human" element is everything human related and can in relation to PPPM best be described as "stakeholders". Knowing stakeholders and their relation to the situation is important but to understand all elements of the situation is even more important. By knowing the other elements of the situation a project/program manager can mitigate even more risks and uncertainties that are dwelling in the complexity of their activities.

Situational mapping is an analytical tool and a prerequisite to another situational analysis tool Development Arena[2][1], when used can give a better understanding of the situation the project or program is trying to change. Situational mapping consists of three different maps; Messy map, Ordered map and Relation map. The maps can be worked with in a chronological order with the last being the relational map or all three maps can be worked with simultaniously, continuously reitereating the maps diving deeper into the analysis, if the time frame allows for greater abstraction. The nature of projects being that they have a set time frame may result in working with these maps somewhere in the middle of these two options. For programs and portfolios which doesn't have this set time fra, one could imagine that the maps would be reiterated upon throughout the entire lifespan of a program or portfolio.

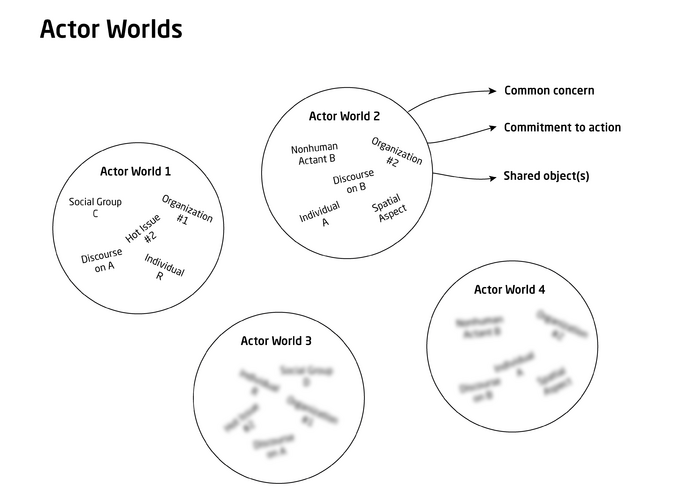

As one goes through the steps of analysing the situation with the three maps the important aspects becomes clearer and subsequently the different actors human or non human each with their unique relationship to eachother or maybe the same common concern, commitment to action or shared objects will form based on these three into Actor-worlds [3], which in this article is presented as a fourth additional map. Eventually they will start to populate the Development Arena[2].

Situational mapping can be seen as an advanced stakeholder analysis where not only the stakeholders are populating the arena but literally everything else that can have a sizeable impact on the project, program or portfolio is mapped and accounted for.

Introduction

Prior to delving into the methods of situational mapping, it is imperative to know and understand how the method came to be, as this establish the basis for the acknowledgement of the tool.

Situational mapping is a situational analysis (SA) tool developed by the American sociologist Adele E. Clarke as an extension of another socioligical analysis theory called "Grounded Theory" (GT). GT was developed by Barney Glaser and Anselm Strauss’ back in 1967, when they published "The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research"[4]. It is possible, that some may already know, that GT is a qualitative social research methodolgy that can be accomodated when trying to understand and analyse imperical data. The method uses the inductive reasoning framework, which seeks to formulate a theory based on the actual data rather than having a set of theories and models fit the data (deductive reasoning)[5]. Theory that blossoms from the collected data is more likely to be true and look like the real world, compared to theory that stems from experiences and speculations of how one believes things should be[5]. Adele E. Clarke was a student of the two and had therefore worked with GT for a long period of time before she in 2005 published the book: "Situational Analysis: Grounded theory after the Postmodern Turn"[1].

In her book Adele E. Clarke put forwards three main situational maps; "Situational maps", "Social Worlds/arenas maps" and "Positional maps" (the lather being a strategy for plotting positions articulated and not articulated in discourses, which is not covered in this article). With these, Clarke articulates a different way of codifying the imperical data which instead becomes much more visual drawing parallels to another theoretical framework used in qualitative researh, namely Actor-network theory (ANT) [6]. Although, these two framework come very close to describing many of the same elements and mechanism in a social context, the difference lies in the nature of the focus and scope of the analysis. While SA seeks to develop a theory of the social context[1], ANT is more concerned with the broader view of the creation and maintenance of socio-technical networks[6]. In the context of project, program and portfolio management, it is relevant to set aside their differences, as these are mainly rooted in the study domain and not so much of the practicalities of the methodology.

In reality, it becomes even clearer to what extend the two line of thoughts cross paths with eachother, when Clarke mentions the notion of Social worlds/Arenas maps as the second "situational map". Evidently, the construction of Social worlds and Arenas maps is closely linked to the theories of Actor Worlds [3] and Development Arenas articulated in ANT, given the founding theories, being GT and ANT their spatial aspect respectively.

Even though, the theories originate from their seperate domain, it doen't make the method less useful for project, program and portfolio managers. In this article, it is argued that situational mapping can be used as a precursor for the development arena, which admittedly is where the real use lies. However, one can't just without preparation, thoughtlessly jump into the method of the development arena. In order to make the most out of it, one should go through the preliminary steps of situational mapping to reveal and fully understand the situation of which the project, program or portfolio engages.

In the following section, the methods of situational mapping is described.

Situational maps - a precursor for the Development Arena

As it is reasoned in the introduction, the SA framework of situational mapping can be used together with the Development Arena framework to gain a more comprehensive understanding of a complex social situation. Situational mapping provides the necessary starting point for analysing the situation, while the development arena only then can provide the broader framework for understanding the context of the elements in which that situation is taking place. Situational mapping consists of three different maps, these are the top three in the list below. The fourth on the list is not a map persay but instead a concept for which the two frameworks (Situational mappnig and development arena) are bridged together. The concept is called actor worlds or social worlds[1] (as Clarke frames it).

- Messy Map

- Ordered Map

- Relational Map

- Actor Worlds

In the next feew sections an explanation of the maps and how to use them is described.

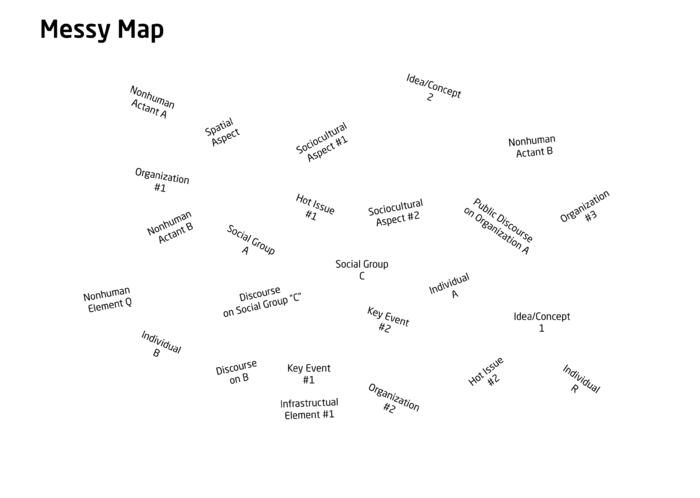

Situational Mapping Part 1: Messy Map

The messy map[1] is the first part of the situational mapping tool (see fig. 1). The principle with the messy map is to identify and also define different types of elements both human (individuals and groups) and non-human (objects, discourses, issues etc.). It feels much like a brainstorming activity, which is exactly what it is suppose to. It is also not the objective of the mapping to finish it but rather the process of the mapping itself, which is what makes up the analytical results. It is however important to keep this part of the analysis messy, as one may feel reluctant to order and structure the empirical data from the get go. if one were to order the data as it came into light, the usual suspects of elements could obstruct and impair the field of view of other elements or how the elements act. When engaging in the situational mapping, one could argue, that the first thing to overcome is the cribbling anxiety, that the chaos and mess the first map encourage one to do. It does make it easier, that the name of the map itself is 'messy map' and that chaos is preferable and it is the sheer premis of the map, that elements may vary in the level of abstraction[7].

With the messy map every conceivable thing related to the situation can be put down, but to make the tool even more applicable to new users, the list below should give some ideas to what these elements might be and what to look for in imperical data one has gathered about the situation.

- Who are the main human actors; - individually, social groups, organisations etc.

- What are the nonhuman actors; Technology, Weather, infrastructure, material things

- What are the discourses; discourses within social groups, organisation or even society

- What are the major issues; related to the situation

- What are the sociocultural or symbolic elements; religion, race, gender, sexuality etc.

- What are the spatial elements; geographical aspects, local, regional, national, global etc.

The list is not a 'check list' and what is relevant in one social context might not that relevant in another. The analytical method only sets the framework and should not dictate the content or outcome of the map, which could lead to a controlled production of empirical data, that would in advance fix the observations [7]. This would mean, that the elements that really matters to the current problematisation or 'concern' is completely overlooked. However, it is of course necessary to have some analytical boundary of the data collection, so that it in turn dosn't become an accumulation of facts, that can't be used for anything.

So when is the mapping done and good enough? The messy map can be iterated upon until it feels 'saturated'. From one map-iteration to another, different elements can become obsolete and others can become more important. The map becomes saturated when one has worked with the maps repeatedly, made adjustments and when... "it has been quite a while since you felt the need to make any major changes"[1].

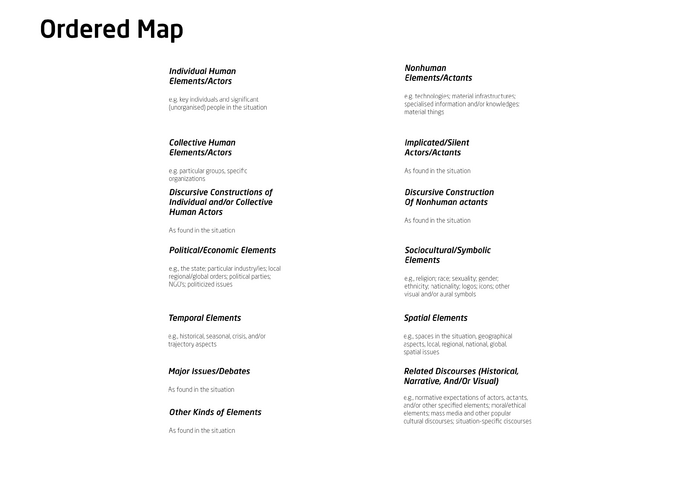

Situational Mapping Part 2: Ordered Map

As on becomes more and more in tune with the messy map and begins to see some overlying categories, one can begin the work of the ordered map. The ordered map (see fig. 2) is the second map in the analysis and is made using the data from the messy map. The intention with this map is to order the findings in the analysis as the "messy map" can be quite eerie to look at as it expands and become more complex. The way one structure and order the elements from the messy map is up to oneself but it might be a good starting point to order them into the categories seen in fig. 2[1]. As one gets acquainted with the methods and the tool, ordering the data into other categories more suited to the actual situation might become more useful. The maps are not static entities, despite there apperance, and can be changed whenever is needed. This map is just one other iterative step in the process, and although the map is based of the data from the messy map, it can also contribute to the expansion of the said messy map[7].

The goal is not to fill in the blanks, but to instead really examine the given situation thoroughly, and thus making the ordered Map is not an essentiel step to understand the situation and can in some cases be skipped completely and the analyst can move straight to the next map, being the relational map (see fig. 3)[1].

Another and often used approach is the continuos iterative approach where the ordered map serves as the prelimenary map to the "Actor Worlds" where the elements from the "messy map" is directly ordered into spaces of where they belong. This can be done in a project context, where the time frame is limiting the analytical processes.

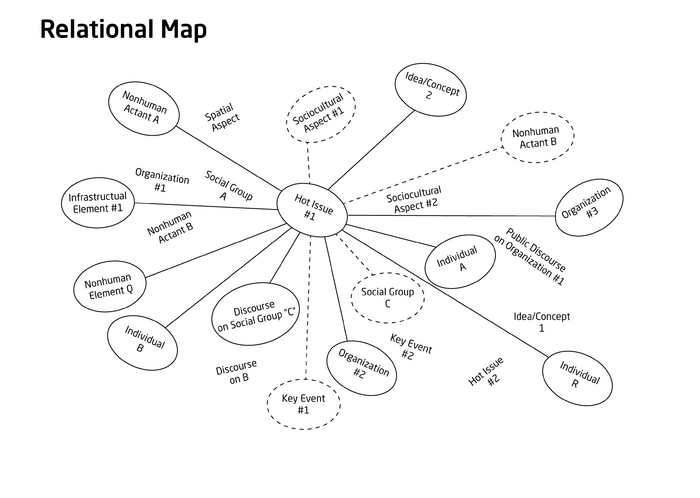

Situational Mapping Part 3: Relation Map

The relational map is the third map in the analysis (see fig. 3) and builds upon the previous situational maps, knowingly that these might change as well once the relational map has been worked with, hereby continuing the iterative process. The starting point of the relational map might be an ordered map, where actors and actants have been grouped together in prelimenary actor worlds or it might be the latest version of a messy map, if there is time to analyse each relationship between every element. This article will focus on the latter. To begin the analysis, the relation between each element on the messy map is described by drawing lines between them and state the "nature" of that line. The analyst does this systematically one element at a time to give each relation attention and reflection. One can use as many copies of the messy map as there are elements on it to then again make as many relational maps one sees fit to diagram through this analytical exercise. In reality, this part of the situational mapping is where the majority of the work is done, once it is constructed [1]. To suit the needs of the analyst the relational map can be done very informally and personalised. One might consider to use different style of lines, colours or even symbols (squares, triangles, bolts, hearts, stars etc.) to describe key relationships between one element and another.

The method itself seeks to clarify what relations are the most important in relation to the given situation, and thereby aid in the decision making of which relations to pursue (based on the empirical data). Typically this process will also contribute to new elements being added and others then removed as it was also explained in the section of the messy map. Again, there isn't a chronological order to the maps, but it is necassary for the explanation to present it this way.

The nature of the 'relational map' might seem tedious to the process, however they do give a systematic, coherent and potentially provoking way of embracing the astounding complexity, whict the situational mapping contains. Even though, this approach creates order and puts things in systems, chaos is inevitable. It is important keep acknowlodging the complexity of the situation always remember that the situation is ever changing.

Situational Mapping Part 4: Actor Worlds - "bridging Situational Mapping and Development Arenas"

To bridge the theory from Situational mapping and Development Arenas, the concept of actor worlds or social worlds as Adele E. Clarke frames it, becomes the underlying foundation for this, as it these that populate the development arena[8]. The two concepts are used interchangeably to describe the following; An actor-world is an analytical social construct, meaning that in reality they do not exist. They consists of actors, non-human actors and groups of actors such as organisations. The discourses, related to single actors or a group of actors, are what define the boundaries of these actor worlds. In theory, the actor worlds are constituted around a particular common concern, which in turn yields the momentum for actors and group of actors to form alliances with each other and objects, hereby having the same commitment to action and shared objects to hereby adress the common concern[8]. An actor world always consists of these three elements and it is what distinguish one actor world from another, however one actor world can unanimously share one or even two (but not all three!) of these elements with a different actor world. If they share all three, their is no arguement for why they couldn't be the same actor world.

Having worked with the situational mapping before turning to actor worlds and the development arena results in a more truthful depiction of the social context. Through the iterative proces of mapping out the discourses and relations between actors, these actor worlds almost defines themselves. Once they are defined, they can now populate the development arena.

Situational mapping as a PPPM tool

The soul purpose for why this article has a part on this wiki site, is because it is reasoned and argued for that the tool of situational mapping can serve as a critical tool for project, program and portfolio managers. This section will disccuss the applicability for managers and why it could potentially leverage their management of either of these.

Application

Overall, situational mapping is a tool that can be used by managers to get a complete overview and understanding of the situation and although it can be used seperately from the development arena, the application of situational mapping is even better when used together as it is on the development arena where actions from the manager along with the other actors and actor worlds (stakeholders) become visible through translations, negotiations and displacements on the arena. it is therefore reasoned, that it is the collectiveness of both these tools that make the application so great.

For project managers situational mapping can help them understand the social context and its elements in which the project is taking place and to identify potential stakeholders and their interests. This can in turn be used to make informed decision-making and project plans. The managers can also identify potential risks and opportunities to then develop strategies for adressing them. Furthermore, by gaining insight into the attitudes, beliefs and values of key stakeholders, project managers can better manage communication, negotiate support and build partnerships with stakeholders to ensure project success. Most importantly the situational mapping can help project managers to evaluate on the progress of the project and its impact of the entire social context/development arena (has the translation of the project resulted in the wanted displacement on the arena?). It is important to remeber, that even though a project might have ended, the social context of where it has taken place never ends and never does the development arena either. Wich leads to the next type of management domain, program management.

For program managers situational mapping can help them in much the same way as the project manager, but because the method is so context specific the tool can also be used to zoom out from the project context level to a program level context moving a step further out in the meso-level (ref), hereby gaining a more hollistic view of the context the program is operating. Programs are defined under the ISO 21500 as "a group of related projects managed in a coordinated way to obtain benefits and control not available from managing them individually" [9]. Argueably, there is a need for a hollistic framework to monitor activities on the program level and the development arena with help from situational mapping can provide that. The tools can be valuable for program managers in developing strategies for achieving the benefits of the program in an environmental, social and cultural sensitive way.

For portfolio managers situational mapping can be a cornerstone for managing projects on a portfolio level. It can help them to prioritise projects based on their potential impact on the context, to then focus their investments on projects that the the greatest potential to not only leverage the benefits of the portfolio but also to create positive social change, if that isn't already a part of the vision or mision statement of the portfolio. It can also help portfolio managers to understand the dynamics that may affect the implementation and success of their portfolio of projects and programs. Moreover, portfolio managers can apply the same approach as stated above in 'project management' to ensure success of every activity in the portfolio.

The nature of projects, programs and portfolio allows the tool to be worked with in different ways. For a project manager it might be most suited to use the method in a chronological manner, going through each maps with little to no changes of the previous map, that would subsequently end up changing the following map. For program and portfolio managers the tool can be used more as intended because of the inherently longer lifespan of programs and portfolios, resulting in an even better understanding context these operates in[9].

Discussion

Although situational mapping can be a useful tool for project, program and portfolio managers, there of course some limitations to consider.

Limitations in application

- Time and resource-intensive: Situational mapping can be a time and resource-intensive tool for managers to use, because it often requires a significant investment in data collection and the anlysis thereof. This could impose a challenge for many project managers, as they are often under a tight timeline and budget.

- Insufficient generalisability: What is found in the analysis of Situational mapping is often specific to certain context, meaning that it may not be generalisable to other contexts. In truth, this can limit the practicality of the tool for project, program and portfolio managers, as they perhaps work across a variety of projects and contexts.

- Subjectivity: Situational mapping is a qualitive analysis tool relying on the perspective and experiences of individuals. As such it is a subject to bias, and may therefore not provide a completely objective view of the situation.

- Overwhelming amount of data: The amount of data generated of situational mapping can be overwhelming, making it dificult for project, program and portfolio managers to priorities and act upon the most important and relevant findings.

All of these limitations can however be accounted for and can also just be seen as pitfalls when engaging in the method, as it is with other analytical tools.

The tools relation to the four core pratices or perspectives of PPPM: "Purpose, People, Complexity and Ucertainty"

Situational mapping can be used by project, program and portfolio managers in adressing the four core practices of project management by providing an increased insight in the social context of each of their domain. And although it can be used as a seperate tool, the relation to four perspectives, shall in this case also be understood as it's contribution to the Development Arena, for which the relation to PPPM is inherently more clear. The contribution of situational mapping to each of these perspectives is desribed here:

Purpose: For the purpose perspective, Situational mapping provide key information about a range of different aspects and elements related to the situation. Some of these relates to the controversies or hot issues as they are described in the theory or maybe former important translations resulting in large displacements of some of the actors or actor worlds. Typically the PPPM wish to change or maybe even keep the sitation as is, which effectively will have an impact on the situation and it's actor worlds. By knowing these elements and insights of the social context, the chance of defining the right purpose and developing the correct understanding of what needs to be achieved has become increasingly more clear.

People: For the people perspective, Situational mapping can help identify important information about key stakeholders and stakeholders not initially accounted for, for which the tool shows its true strength and purpose. By conciosly analysing discourses, historical events, controversies and translations related to these actors, the PPPM can enhance its understanding of their different perspective and experiences. This will help the PPPM to manage its stakeholders both internally and externally out side of its organisation building better relationships and unnderstanding their needs and engagement to the project, program or portfolio.

Complexity: For the complexity perspective, Situational mapping can relieve managers in understanding the different aspects of the situation, whether that will be social, cultural, historical, technological, politcal etc, which in turn will have an effect of the success and outcome of the project, program or portfolio. Subsequently, better strategies for dealing with the complexity can be developed even before they either become a threat, that needs to be dealt with.

Uncertainty: For the uncertainty perspective, Situational mapping can be a vital organ when dealing with uncertainties. The reason being, that the increased understanding of the project, program or portfolio context, that the tool provide, helps managers to identify the uncertainties, so that they can in a timely manner manage them and adapt to any changing circumstances.

Concluding remarks

This article has introduced the reader to the methods of situational mapping, a situational analysis framework for understanding complex sociol contexts, developed by the american sociologist Adele E. Clark as an extension of Grounded theory. It also depicts the concept as a tool that, when used in practice in a project, program or portfolio related context, can act as the precursive analysis tool the development arena. The tool however, was not developed for the intention of the management of these, but instead was thought as a reasearch framework in the domain of social science. In the years after the method has been adopted by a wide range of other disciplines [10], who have used the framework to expand their own field of work, why this has also now become a method for engineers to understand the sociotechnical aspects, when driving innovation forward [7].

Situational mapping is a comprehensive tool for understanding complex social contexts and its elements such as different discourses, actors and non-human actors. It takes it's starting point in the vast imperical data sought from various heteregenous sources, which are gathered continously through out the process of mapping the situation. These sources can be but are not limited to interviews, historical documents, meetings, legal documents etc [10].

The method aims to clearify the vast complexity of a given project, program og portfolio context, so managers can act accordingly, develop the strategic processes for their activities and monitor the success of these. The development arena [2] should be the final outcome of the situational mapping and it is therefore adviced for anyone who strive for using the full potential of the tool to get acquainted with this. The reason being, that it is here the full picture, of the actions of oneself and other stakeholders, becomes evidently more clear [2].

Annotated bibliography

It is suggested to read the following litterature below to gain an even better understanding of the theory and its use in practice.

- Clarke, A. (2005). Doing Situational Maps and Analysis - Situational Analysis: Grounded Theory after the Postmodern Turn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [3]

This paper outlines the situational analysis method of situational mapping, and how it is use the context of social science. Clarke frames three different kinds of maps, which can be used to understand the social context of a given situation.

- Clarke, A., Washburn, R. & Friese, C (2022). Situational analysis in practice : mapping relationalities across disciplines [4]

This paper is an extension of the work previously done by Clarke especially. Here the three women dives into the cross disciplinary aspects of the situational mapping developed by Clarke.

- Jørgensen, U. & Sørensen, O. (1999) Arenas of Development - A Space populated by Actor-Worlds, Artefacts and Surprises [5]

This paper outlines the theory of development arenas and actor-worlds. They argue for having a discussion that bridges the theory of ANT and development arena with the more common theory and practices of managers.

- Anne Katrine B. Harders (2015): Situationsanalyse. Chapter in: Stædige infrastrukturer og genstridige praksisser: Et praksisteoretisk studie af byudviklingsprojekter mellem vision og realitet. Department of Planning, University of Aalborg [6]

This is a PhD report by Anne Katrine B. Harders of Aalborg University. In this she uses the framework of Adele E. Clarke to analyse the situation of city development. The method is used here in a project related context.

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 Adele E. Clarke (2005): Doing Situational Maps and Analysis. Chapter in "Situational Analysis: Grounded Theory after the Postmodern Turn", Thousands Oak Sage: page 83-144, https://doi.org/10.1525/si.2003.26.4.553

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Jørgensen, U. & Sørensen, O. (1999): Arenas of Development - A Space populated by Actor-Worlds, Artefacts and Surprises https://doi.org/10.1080/095373299107438

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Michel Callon (1986) The Sociology of an Actor-Network: The Case of the Electric Vehicle. Chapter in Michel Callon, John Law & Arie Rip (eds.) ' Mapping the dynamics of science and technology ', London: Houndmills, p. 19-34. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-07408-2_2

- ↑ Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967): The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. New York, NY: Aldine De Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203793206

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Merete W. Boolsen. (2015): Grounded Theory. Kap 12 i Brinkmann & Tanggaard (red.) ' Kvalitative metoder - en grundbog '. København: Hans Reitzels Forlag. 2. udg. p. 241-271 Book: https://hansreitzel.dk/soeg/kvalitative-analyser-bog-15605-9788741259833

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Torben Elgaard Jensen (2005): Aktør-netværksteori - Latours Callons og Laws materielle semiotik. Chapter in A. Esmark., C.B. Laustsen og N. Å. Andersen (red.) Socialkonstruktivistiske Analysestrategier. Roskilde Universitetsforlag: Samfundslitteratur, p. 185-210. https://samples.pubhub.dk/9788778674401.pdf

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Anne Katrine B. Harders (2015): Situationsanalyse. Chapter in: Stædige infrastrukturer og genstridige praksisser: Et praksisteoretisk studie af byudviklingsprojekter mellem vision og realitet. Department of Planning, University of Aalborg, p. 88-93 Report: https://vbn.aau.dk/en/publications/st%C3%A6dige-infrastrukturer-og-genstridige-praksisser-et-praksisteore

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Clarke, A. & Star, S. (2008): The social worlds framework: a theory-methods package . - The New Handbook of Science and Technology Studies third edition, chapter 5, Book: https://www.dhi.ac.uk/san/waysofbeing/data/data-crone-wyatt-2007b.pdf

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Project, programme and portfolio management – Context and concepts : DS/ISO 21500:2021 https://sd.ds.dk/Viewer/Standard?ProjectNr=M351701&Status=60.60&VariantID=&Page=0

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Clarke, A., Washburn, R. & Friese, C (2022). Situational analysis in practice : mapping relationalities across disciplines https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003035923