Social loafing and expectancy-value theory

Contents |

Abstract

The term social loafing refers to phenomenon of individuals not working or contributing to their full ability when working in a group [1]. This phenomenon can lead to a discrepancy between expected and actuals results of group work, since a team’s productivity does not match what would have been the combined individual effort. The phenomenon was first described in a summary by W. Moede in 1927 detailing rope-pulling experiments by French professor Max Ringelmann done in the late 1890s [2]. The term social loafing was later introduced to the phenomenon in 1979 by Bibb Latané et al.[3]. The term has since been widely used and subject to extensive research with over 100 studies examining the phenomenon, covering both laboratory experiments and field research[4]. This has led to many more advanced theories of social loafing.

Looking at the phenomenon from a project management angle, team effectiveness is a major part of any project involving multiple people of actors working together and social loafing is a robust phenomenon with the potential of lowering effectiveness. Thus, social loafing should be accounted for, when managing projects.

A theory that can help account for social loafing is called Expectancy-value theory. Expectancy-value theory provides a framework for assessing an individual’s effort motivation, based on three main factors: Expectancy, Instrumentality and Outcome value[1]. These models suggest that individuals are most likely to contribute to their full ability when their work is necessary for the project and when their efforts results in something they value highly. Put in relation to social loafing this suggests that work in groups or teams may have less obvious links between effort and outcome and/or a less obvious link between effort and rewards.

Big Idea

While not defined as such, doing projects almost always requires some degree of teamwork. Therefore, a project manager should be aware of the mechanisms and dynamics which takes place when multiple people work together. A well-documented mechanism that negatively affects the efficiency of group work is social loafing. Social loafing describes a phenomenon where the sum of individual efforts in a team task does not match the sum of individual potential. The phenomenon was first described by French professor Max Ringelmann, who wanted to study the correlation between individual efforts and sizes of groups which said individual was put in. Ringelmann tested this correlation by having test subjects pull a rope both individually and in groups. This experiment showed that the force exerted by the group did not match the summed force of each individual of the group, had they pulled the rope without being in a group [2]. Since Ringelmann, the effect has been demonstrated across numerous studies, most famously by Latané, Williams & Harkins who created similar experiments to the rope-pulling experiment except for subject having to clap or shout instead of pulling a rope. Not only did these experiments validate Ringelmann’s findings they also helped put the significance of the effect into perspective. The clapping and shouting experiments demonstrated how severely individual performances declined when put in a group. Latané, Williams & Harkins’ experiments showed that individual performances was reduced to 71% when in two-person groups, 51% when in groups of four and just 40% when in groups of eight[3].

Since the introduction of the term social loafing, several theories have been developed in order to describe the underlying causes of the phenomenon. An interesting example of this is expectancy-value theory which pertains to effort – both individual and in group tasks.

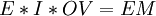

Expectancy-value theory offers a way of quantifying a person’s motivation towards a given task – thereby also indicating a likelihood of social loafing. Following expectancy-value theory this measure of motivation is named effort motivation (EM) and given by the multiplication of three factors: Expectancy (E), Instrumentality (I) and Outcome value (OV), as given in the formula below [5] [6]:

Expectancy, E refers to a perception of performance relying on effort, i.e., that a greater display of effort will lead to better performance and thereby results. This component ranges from 0 to 1 i.e., from no relation between effort and performance to full correlation between effort and performance.[1]

Instrumentality, I is defined as the perception of contingency between the outcome and performance. This means that instrumentality is based on an expectation of to what extent the quality of a performance will be reflected in the outcome of the performance. The instrumentality component also ranges from. 0 to 1 i.e., from performance having no effect on the outcome to performance and outcome being fully correlated.

Outcome Value, OV is simply how an individual values achieving the outcome of a performance, including the subtraction of potential costs. Essentially outcome value is perceived reward mines perceived cost. This component ranges from -1 to 1 i.e., from not rewarding and very costly to highly rewarding and not costly.[1]

Effort Motivation, EM is, in essence, the degree of effort which an individual is willing to exert in order to complete a specific task or goal. Based on the three intrinsic components, the effort motivation can range between -1 and 1. If the value is near 1, this means that an individual’s motivations for putting in effort is high, while a value near 0 or a negative value indicates low motivation.[1]

It is important to note, that the product of equation, the effort motivation, is based on an individual’s perception of the three dimensions expectancy, instrumentality, and outcome value, which might not at all be similar to factual values. If the model is not based on an individual’s perceived values, it may lead to some confusion, as a test subject may perform actions which seem deeply irrational based on the model but are completely rational to the subject.

When examining the expectancy-value theory’s implications on group work, it becomes evident why the theory has been used as a framework for understanding and explaining causes of social loafing. Of course, all three dimensions of the expectancy-value theory can be applied on individual work, however, it is evident that group work greatly affect the three dimensions of the equation. When working in a team, expectancy is likely to drop because of efforts being pooled which makes the overall performance rely less on each individuals’ efforts. Instrumentality is also likely to drop due to the relationship between individual performances and a group reward. If members of a team are rewarded equally, there is likely one or more members whose reward do not match their perception of their own effort. Lastly, it is highly unlikely that all members of a team value the outcome of their work equally. This difference in perceived outcome value may lead to team some members being less inclined to putting in effort than others, even should the previous two factors be equal.

Application

When managing people, which is a given in project, program and portfolio management, one should try to maximize the effectiveness and efficiency of individuals by understanding differences in motivation among project team members [7]. One way to do this is to combat social loafing, which greatly decreases efficiency of individuals working in teams. This can be done, by understanding motivating people. The expectancy-value theory gives and excellent starting point for a project-, program- or portfolio-manager to manage individual motivations. Given that the theory framework suggests that effort motivation is given by multiplying expectancy, instrumentality, and outcome value, naturally, effort motivation will be low if any of the three factors are low.

Expectancy

When dealing with the expectancy dimension, two factors are important to have in mind when managing teams. The first is value(or dispensability) of team members individual efforts and the second is team members perception of their likelihood of success or high performance.

In 1982, Harkins and Petty published an article containing several studies investigating the effect the dispensability of an individual’s performance had on social loafing. In one experiment, subjects were given the impression, that their efforts where crucial to a good performance, due to the high difficulty of the task given. The experiment showed that subjects given a more difficult task exerted greater effort than those given an easier task. More surprisingly, perhaps, subjects with a more difficult task exerted greater effort even when their contribution could be identified. Another experiment Harkins and Petty changed the dispensability of individual efforts by manipulating a subjects perception of the uniqueness of the task they were given. On top of this, they also compared the subject’s efforts when of the impression that the task was either anonymous or clearly identifiable. Here, results showed that participants exceeded greatest efforts when the task was unique and their work identifiable and the least effort when tasks anonymous and non-unique[8].

Studies have also highlighted that the belief that high collective performance is based on individual performance plays a role. In 1983 Kerr and Bruun conducted a series of experiments of were participants would be paired up to complete tasks. The experiments showed that highly skilled participants worked harder on tasks where their own effort lead to personal rewards than tasks where both members efforts were pooled. For lower skilled participants the results were the opposite. Put simply, when participants perceived their efforts as crucial to the team performance, they exuded greater efforts[9].

Summing up these three findings, to ensure high expectancy, a team manager should try to make sure that individual tasks are to the greatest degree possible; challenging, unique, identifiable and important to overall team performance.Lastly, it is worth noting that studies have shown that if the likelihood of a good overall team performance is low, all three factors loose importance and the overall expectancy drops due to individuals not being willing to work hard if chances of success are remote[10].

Instrumentality

Investigating the effects of instrumentality, a managers main concern should be to ensure that incentives for individual efforts exist, and that the value of these incentives are greater than the cost of individual efforts.

In 1999 Shepperd and Taylor conducted an experiment to test the effects of either high or low probabilities of efforts being either rewarded and/or evaluated. They did so by having participants working in groups on tasks with either a high chance of a reward (high instrumentality) or a low chance of a reward (low instrumentality). Simultaneously they also investigated the effect of participants performances being individually evaluated regardless of their chance of reward. They found that individuals working on tasks with high instrumentality performed equally good, individual evaluation or not. Individuals working on tasks with low instrumentality but with individual evaluation performed equal to the teams with high instrumentality. Teams with low instrumentality and no evaluation performed worst, indicating social loafing[10].

Summed up, team members will perform better and work higher, if they perceive the probability of a reward upon a good team performance is high. Opposite, if team members think that there is a low likelihood of a reward for a good group performance, their efforts will lessen.

Outcome Value

The mechanisms which a team manager should be aware of, when investigating outcome value can be summed into three categories: Incentives for individual performance, Incentives for group performance and lowering of contribution (effort) costs.

Incentives for individual performance

Incentives for individual performance fall into two categories: external and internal incentives. External incentives are perhaps the most commonly recognized, being tangible things such as bonuses, raises or other types of rewards. However, it should be noted that incentives also work the other way around as team members can be sanctioned or terminated. Further, external incentives should not be considered limited to tangible rewards. Intangible rewards such as social rewards in the form of approval for example, or the avoidance of social sanctions also play a role in individuals’ perception of outcome value[5]. However, in order for individual performances to be rewarded, said performance must be evaluated in some way. In connection to this, multiple studies have shown that if members of a team are under the impression that they are, or atleast can be, evaluated individually, they perform better[11] [12].

Internal incentives are perhaps not as commonly thought of as external incentives, but also play their part in an individual’s perception of outcome value. A study by Szymanski and Harkins in 1987 highlight that the opportunity to self-evaluate increased participants performance. This suggests that one way of providing internal individual incentive is to provide team members with the possibility to evaluate themselves. Another, perhaps more obvious, internal individual incentive is simply to work on intrinsically interesting tasks. Generally, people will work harder on tasks which satisfies the conditions of seeming meaningful or leading to a personally relevant outcome[13].

Incentives for group performance

Incentives for good group performance can be key for a team leader, as incentivizing on an individual level can be difficult in teamwork where the outcome is based on the sum of efforts. Like for individual performance, incentives for group performance can be divided into two categories: internal and external incentives.

Studies have shown that external incentives for a group performance such as monetary credit will increase the performance of team members. When no incentive for good group performance is offered, individual team members will exude less effort than if an incentive for a good group performance is present[14].

Internal incentives for group performance occurs when team members feel a strong connection to their team and/or their team members. This can make individuals take pride in their work or give a heightened sense of duty, both positively adding to individual motivation. This effect was shown in a study in 1997 where participants were put in a speed-typing competition in teams. Here, participants who believed that they were in a team with their friends typed significantly faster than those convinced they were in a team with strangers[15]. This effect is important to note as a team leader, as it helps confirm the fact that teambuilding is not just beneficial to individuals comfort, but also to motivation and performance.

Minimizing cost of contributions

Since the outcome value also represents the subtracted contribution costs, it is obvious that a lowering of contribution costs heightens the outcome value and thereby the effort motivation. Of course, contribution costs can be material and tangible but for working in groups, in many cases, it is a psychological cost. Essentially, if an individual feels that they are exuding great effort and that team members are “free-riding” of their effort, they might lower their own effort[15]. Three methods that can help a team leader reduce these psychological costs are:

1. Divide and conquer. This method is perhaps the most obvious and simple. If the task of a team is divided into smaller tasks and delegated to individuals, there is no longer an opportunity for loafing.

2. Convince team members that efforts are equal. Another way of lowering psychological cost is to convince individuals that all team members are working with equal effort. By doing so, the individual members potential fear of pulling the load is reduced. In fact, studies show, that individual efforts heighten, when told that other team members are exuding a similar effort, in order to not end up free-riding others[12] .

3. Punish loafers. The third method of lowering contribution cost is simply to evaluate individual performances and make sure that necessary steps are taken if a team member is not performing as intended. Although, it may not be necessary to actually evaluate and punish loafers, in many cases team members knowledge of such a procedure could be enough for performance to stay high.

Lastly, one should remember that increasing outcome value is a balance between incentivizing performance and minimizing costs of contribution. Therefore, a team leader should always carefully assess whether it is best to increase incentives or lower costs based on the team and the project.

Limitations

While both the phenomenon social loafing and the expectancy-value theory are well-documented, no framework has been developed rigid enough for project managers to use it as a tool on its own in a plug-and-play manner at least. As demonstrated in the “application” section the expectancy-value theory does provide a guideline for factors and element which play a role in the motivation individuals working in teams. However, it acts as a mere guideline or checklist more than a method.

Points can also be raised about the accuracy of the theory. Namely, the theory does not account for individual personal og cultural differences. Weiner has found that certain personality traits also greatly affect individual predispositions. Weiner states that an individual’s “need for achievement” has the potential bias the weighting of factors affecting motivations. Individuals high in achievement needs has a tendency to value both effort and ability highly in success, while mainly attributing failure to low effort. Individuals low in achievement effort, on the other hand, does not attribute success to either effort or ability, but instead to external factors such as luck. In failure, individuals low in achievement needs tends to view low ability as the factor with the biggest influence[16]. These findings have however, been combated in later studies. In 1998 Charbonnier, et al. found that personality traits do not affect does not affect an individuals proneness to social loafing. In fact, quite the opposite is true. [17]

A simple model for a complex matter

From a more mathematical theoretical standpoint, some researchers argue that the definition of instrumentality as a probability, based on the factor ranging from -1 to 0, is faulty, and that is should be considered as a correlative value, thus ranging from -1 to 1. [5] Besides this dispute, it is worth considering the accuracy of the model. Expectancy-value theory gives the impression that all three dimensions are equally important as they range from -1 to +1, however this probably rarely the case, and to get a precise indication of effort motivation, one would need to compare the weight of each dimension rigorously. But even then, what does the product of the equation mean? There is really no good answer, and so the relevance of the equation stems more from its categorization of elements and their relationship than it does from its product.

Lastly there is a good chance that using the expectancy-value theory will results in head scratches and the posed question “when is enough enough?” To which, again, there is no straight answer. Essentially there is no simple way of making sure or even reaching a point where all dimensions of the model are fulfilled. This is especially evident in team work, where the model applies for each individual and contains values based on their personal perception. Therefore, an argument can be made that the actual application of the mathematical equation would be to misunderstand its use. Instead, it should be used as a guideline which highlight the relations between several complex factors leading to effort motivation.

Annotated Bibliography

- "Many hands make light the work: The causes and consequences of social loafing", Latané, B., Williams, K., & Harkins, S. , 1979, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37(6), 822–832.

- The article introduces the term social loafing, and has been used as a key article and starting point for countless studies examining the effect since its release. The article both presents the phenomenon thoroughly, but also seeks to describe several underlying factors, which could explain the phenomenon.

- "Social loafing and expectancy-value theory" Shepperd, J.A. , 2001, Multiple Perspectives on the Effects of Evaluation of Performance: Toward an Integration, 1-24.

- Shepperd briefly introduces the terms social loafing and expectancy-value theory, explaining how expectancy-value theory can be used as a theoretical basis to understand social loafing and its causes. Shepperd then proceeds to explain the three factors expectancy, instrumentality and outcome value in depth, also addressing how potential problems affecting each factor can be mitigated.

- '"Work and Motivation" Vroom, V.H. , 1964, New York: Wiley

- A true landmark when published. In this book Victor Vroom compiles hundreds of studies on individual workplace behavior. Central to this article and expectancy-value theory are chapters 7 & 8, which deals with the role of motivation in job performance. Although old, this book brought forth an incredible amount of knowledge and has acted as a foundation for the field motivation ever since.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 [Social loafing and expectancy-value theory] Shepperd, J.A. , 2001, Multiple Perspectives on the Effects of Evaluation of Performance: Toward an Integration

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 [“Recherches sur les moteurs animés: Travail de l’homme” [Research on animate sources of power: The work of man]] Ringelmann, M., 1913, Annales de l’Institut National Agronomique, 2nd series, vol 12, pages 1-40

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 [Many hands make light the work: The causes and consequences of social loafing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37(6), 822–832] Latané, B., Williams, K., & Harkins, S. , 1979,

- ↑ [Social Loafing (and Facilitation)] Karau, S. J. , 2012,

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 [Work and Motivation]Vroom, V.H. , 1964, New York: Wiley

- ↑ [Social Loafing: A Meta-Analytic Review and Theoretical Integration Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 65, No. 4, 681-706] Karau, S., Williams, K. , 1993.'

- ↑ [The Standard for Project Management] ,Project Management Institute, Inc., 2021., A Guide To the Project Management Body of Knowledge (Pmbok® Guide) – Seventh Edition.'

- ↑ [Effects of task difficulty and task uniqueness on social loafing] ,Harkins, S. G., & Petty, R. E., 1982., Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 43, 1214-1229.

- ↑ [Dispensability of member effort and group motivation losses: Free-rider effects.] ,Kerr, N. L., & Bruun, S. E., 1983., Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44, 78-94.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 [Social loafing and expectancy-value theory.] ,Shepperd, J. A., & Taylor, K. M., 1999., Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 25, 1147-1158.

- ↑ [Ringelmann revisited: Alternative explanations for the social loafing effect.] ,Kerr, N. L., & Bruun, S. E. , 1981, Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 7, 224-231.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 [The role of evaluation in eliminating social loafing.] ,Harkins, S. G., & Jackson, J. , 1985, Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 2, 457-465.

- ↑ [Social loafing and self-evaluation with a social standard.] ,Szymanski, K., & Harkins, S. G. , 1987, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53, 891-897.

- ↑ [Social loafing: The role of task attractiveness.] ,Zaccaro, S. J. , 1984, Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 10, 99-106

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 [The effects of group cohesiveness on social loafing and social compensation.] ,Karau, S. J., & Williams, K. D. , 1997, Group Dynamics: Theory. Research. and Practice, 1, 156- 168.

- ↑ [An Attributional Interpretation of Expectancy-Value Theory.] Weiner, B. , 1974., Cognitive Views of Human Motivation., 51-69.'

- ↑ [Social loafing and self-beliefs: People's collective effort depends on the extent to which they distinguish themselves as better than others] Charbonnier, E., Huguet, P., Brauer, M., & Monteil, J.-M., 1998., Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 329–340