Staging negotiation spaces in project management

Climate change is a big challenge in the 21st century and necessitates the efficiency that advanced engineering systems can provide. When developing such systems, it is important to understand the difference between those, who use systems and those who build them as they have different success criteria.[1] Trying to combine the system builders’ and the system users’ needs, many projects are of a collaborative nature. However facilitating processes is crucial for projects to be successfully completed regarding cost, timescale and performance.[1]

Project stakeholder management is as much about identifying and analyzing stakeholders and their impact on the project, as it is about developing appropriate management strategies for effectively engaging stakeholders in project decisions and execution.[2] Many projects cracked the code and use socio-technical methods in their involvement of stakeholders, but as projects are iterative processes, circulation and repetition with small changes should be found in the way we work in projects.

The purpose of this article is to introduce the framework staging negotiation spaces as a management strategy with a circular approach and emphasize how a strategic application of the framework can give direction to projects and provide a subtle method to gain valuable information used to engage stakeholders. With key aspects as staging, facilitation of negotiations, and re-framings, the framework touches upon an internal aspect of organizational planning and performance improvement as either a preparation or an outcome of stakeholder engagement, which makes the framework suitable for project human resource and communication management. Introducing the theatre metaphor, which the framework builds upon, it is clear how terms backstage and frontstage creates a circularity of knowledge and an opportunity for a project team to get a common perception of how to interpret and prepare meetings in the process of a project.[3]

Contents |

The big idea

As the word staging indicates, the framework staging negotiation spaces is based on a theatrical metaphor, where a director and the team associated are setting the scene for actors to perform a play. The play has lines, objects, and expressions that altogether become a manuscript. By the same means project managers can be seen as directors whose degree of freedom is strongly related to the production’s budget and positioning.[4] The project manager has to direct the team, which furthermore has to direct stakeholders who are invited onto the stage. The staging metaphor has been used in terms of participatory design, but the framework staging negotiation spaces seeks to expand the theatrical metaphor to include staging within a team of design engineers. The design engineers can also be considered as some of the system builders, however, in this article, they are referred to as the project team, which emphasizes the multidisciplinary team that advanced engineering system builders consist of.

Stage, negotiate and reframe

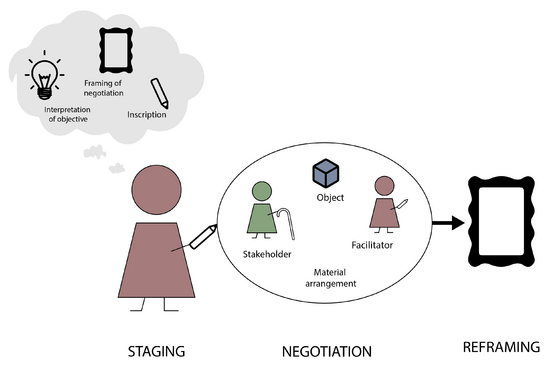

To outline the framework it is essential to introduce three interconnected aspects, namely staging, facilitation of negotiations, and re-framings. These aspects have their origin in science and technology studies (STS) and actor-network theory (ANT), which are both very established understandings in the vocabulary of a design engineer,[4] and yet the framework is doable in a project team.

1. Staging

When the project manager sets the scene, that person is expected to provide their team with a script in terms of an outlined plan or project, as well as they are expected to provide objects in terms of working structures or tools. The phrase staging fits the theatre metaphor, but should be taken with a grain of salt as stages through STS can be seen as a temporary and spatial space.[5] However the framework distinguishes between backstage where the project team interacts, and frontstage where the project team invites stakeholders to interact and co-create.[3] To engage stakeholders, the project team will beforehand discuss in which space the stakeholders are brought together and which objects should make them interact. Lastly, they plan the meeting to make sure that they cover all the desired subjects.

Hence staging is, as the metaphor indicates, about setting the scene either as a project manager or as a project team.

2. Facilitation of negotiations

As a project evolves different members of the project team have perceived events differently, just like stakeholders have different relations to a given problem. For the project to keep evolving the project team has to align their perceptions within the team, just like stakeholders have to comprehend each other’s concerns.[6] In the term of staging negotiation spaces, this is called negotiations and relates to the stakeholders' way of framing their concern. To make sure negotiations remain constructive the facilitator has a toolbox. What is in this toolbox depends on the facilitator’s background and therefore their ability to apply methods or objects to such stages.

Hence facilitation of negotiations comes down to providing team members or stakeholders with tools to get on common ground in their understanding of the subject.

3. Re-framings

Often the stage holding a negotiation creates an opportunity to re-frame the problem or a given situation. As the term indicates, re-framings are about having an explorative approach and thereby being open to learning from every negotiation. Are stakeholders brought together in a well-staged and facilitated negotiation, the project team will afterward know more about the desired subjects and possibly be able to rephrase the problem in terms of their interpretation.[4] It is also a possibility for them to rearrange the stage and facilitation of negotiations with the experience from the previous negotiation.

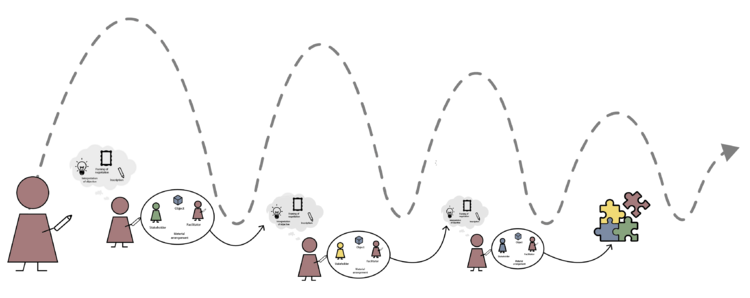

Hence re-framings focus on the iterative aspect of a project, where project teams or managers learn from their staging and facilitation of negotiations so that deliberate adjustments will lead the project in the right direction.

Configuration of spaces

By operating and bringing the three above-mentioned aspects together, negotiation spaces are configured. As shown in figure 1, a part of this configuration is inscription. Inscriptions are relevant because they make it possible for the project team to represent either theirs or a stakeholder's matter of concern in objects. Latour refers to inscriptions as: “all the types of transformations through which an entity becomes materialized into a sign, an archive, a document, a piece of paper, a trace” [7] This means, that the project team process information and somehow incorporate this knowledge in their creation of an object, which can basically be anything; a game, a document, a picture, a trace, and so on. By bringing inscribed objects to a negotiation the project team can influence the direction of the negotiation between stakeholders, and the framework staging negotiation spaces becomes a more strategic tool.

Akrich merely sees inscriptions as an area, where the social and the technical overlap.[8] This means, that these inscriptions are intentions that arise in social dynamics and then build into technical objects. Inscriptions may therefore be what caused a problem in the first case. Akrich describes the elementary mechanisms of adjustment as circumstances in which the inside and the outside of objects are not well matched. [8] This exactly refers to the need for collaboration between system builders and system users, as inscriptions are not always read the way they were intended. If the project team negotiates their different areas of knowledge to the case or interpretations from negotiations with stakeholders, then the activity is happening backstage and may be facilitated by the project manager. If the project team creates a space by bringing stakeholders and inscribed objects then the negotiation is happening frontstage. [3] Either way following the framework the project team interprets negotiations and thereby reframes a negotiation space or the direction of the project to evolve.

Hence the configuration of spaces is rooted in previous experience within the project, which is creating these loops and thereby underlines the iterative nature of the framework. Connecting all the re-framings a project undergoes and combining them with some proper visualization skills, staging negotiation spaces can even become a tool to visualize the process of a project. The visualization will bring out empirical findings, which altogether detail the problem to such degree that it is possible to solve.

Application

The Project Management Institute’s (PMI) guide to Project Management Body of Knowledge mentions the need for progressive elaboration that should be understood as a continuous detailing throughout a project, which only advocates for a circular framework such as staging negotiation spaces. By using this framework where interpretation is the foundation for reframing and furthermore staging and facilitation of negotiation spaces, the project managers and their teams have a language for the planning of meetings with different stakeholders. When considering project management based on the four key perspectives (purpose, people, complexity, and uncertainty), this language is a breeding ground for alignment of the people, who are managed in a project. Backstage discussion of different interpretations, creation of objects to interact with, and role distribution are namely all inherent activities in staging negotiation spaces.

PMI’s guide also mentions how a project team manages the work of the projects, which typically involves:[2]

- Competing demand for: scope, time cost, risk, and quality

- Stakeholders with differing needs and expectations

- Identified requirements

Staging negotiation spaces mostly touch upon the second point and the Project Management Institute’s guide actually mentions the handling of project stakeholders as being a difficult discipline, as: “Managing stakeholder expectations may be difficult because stakeholders often have very different objectives that may come into conflict.” [2] A project team must therefore be very aware of how to facilitate these frontstage activities, which also speaks in the favour of staging negotiation spaces.

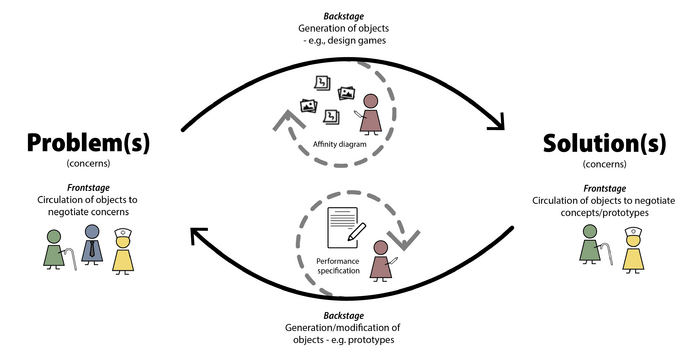

The performance of staging negotiation spaces

To outline the value of a circular framework in management a solution space is drawn upon. As figure 3 shows problems, also known as concerns, are identified by bringing objects for the stakeholders to interact with when negotiating. Afterward a project team structure and discuss their new empirical knowledge backstage by e.g. using an affinity diagram. Keeping this new knowledge in mind they generate objects containing possible solutions and start planning the frontstage activity. The frontstage is being reframed by bringing these newly generated objects and by inviting the most affected stakeholders to negotiate. The outcome of negotiations frontstage is a breeding ground for backstage activities as e.g. a performance specification and thereby modification of the objects containing possible solutions. Bringing the backstage work to the frontstage may cause some new concerns.

A concrete case is found in the book Staging Collaborative Design and Innovation: An Action-Oriented Participatory Approach, where a project team attempts to improve the quality of life for elderly residents with dementia.[3] A common matter of concern was discussed between students and nurses and the nursing home and the result was: "How can sensory simulation technologies be used to ease feelings of restlessness and frustration among elderly residents with dementia”.[3] Based on desk research the project team created an affinity diagram, which they within the team used to negotiate and thereby align perceptions of the field they had to work in. As another backstage activity, the project team developed a design game in which they inscribed meanings based on their knowledge of how to communicate with dementia with residents.[3] Frontstage they framed the negotiation as an opportunity for the residents to describe their experiences with technologies[3], but the design game failed to translate the resident’s concern and backstage the project team had to reflect on what went wrong. Using insights they added simple smiley faces for the residents to communicate with and furthermore facilitated the negotiation in a calm and known environment.[3] By these re-framings the project team eventually managed to engage important stakeholders and improve their team performance.

Area of application in project management

Regarding project human resource management, PMI states: “identifying, documenting, and assigning project roles, responsibilities, and reporting relationships” as organizational planning and the outputs from here as role and responsibility assignments.[2] This qualifies backstage activities in terms of staging negotiation spaces as organizational planning and a link in human resource management processes. Human resource management also contains team development, where inputs as external feedback and tools as team-building activities bring resonance to staging negotiation spaces. External feedback can namely be seen as stakeholders’ response and engagement to frontstage activities, which is up to the project team to interpret and afterward reframe. This interpretation can with a bit of patronage be seen as a team-building activity, where the teams’ performance is improved by revisiting the project team members’ individual experience of a given frontstage activity.[2]

But it is not only the area of human resource management, where the framework staging negotiation spaces is relevant. Project communication management provides the critical link among people, ideas, and information that are necessary for success.[2] This area contains a lot of tools for a project team to consider backstage but is closely connected staging negotiation spaces in terms of information distribution and especially regarding unexpected requests for information. Staging negotiation spaces is well suited for this as the iterative nature of the framework is based on communication, thus the framework elaborates on the information distribution methods as inscriptions are introduced. By adding inscriptions many layers are also added to the communication, which is in combination with iterations what makes this framework stand out. It places high demands on the project team and their creative competencies, but also provides them with a subtle method to gain valuable information.

Limitations

Of course, staging negotiation spaces is not the perfect framework for every project. Some projects address well-defined problems, where the information is sufficient and clients are clear about their requirements, and some address ill-defined problems, where sense-making is done during the project.[10] Staging negotiation spaces has a resonance for the latter approach, where uncertainty has to be operationalized and the project undergoes multiple iterations.

Also, downsides such as time used for planning and alignment are aspects of using this framework, which can cause delays in projects, but sometimes also improve the outcome. It is a balance when enough planning and reframing are done. The framework will especially delay a project or lose its value if the project team is not familiar with how to involve stakeholders properly as it to some extent requires knowledge on how to involve stakeholders. Even if design engineers are a part of a project team, it is not given, that e.g. inscriptions are read the intended way, as Akrich points out.[8] Even though it is not possible always to hedge one’s bets, an advantage is to work in multidisciplinary teams, because it in most cases is a necessity to develop sustainable solutions in the complex world, we are facing.

Depending on the project team's competencies, the framework is durable to the desired extent although it has full eligibility when backstage and frontstage are applied. In this way, interpretation becomes more intentional and re-framing more strategically, which is the breeding ground for team performance improvement. This is also the point, where the framework can be applied to a portfolio level as a portfolio contains several projects, which can benefit from each other. Key learnings in one project are more visible with the staging negotiation framework and are therefore more likely to apply to another similar project. This is also consolidated by the categorization of staging negotiation spaces as organizational planning, as one of the tools and techniques for organizational planning is templates: “Using the role and responsibility definitions or reporting relationships of a similar project can help expedite the process of organizational planning.” [2]

With these words staging negotiation spaces is definitely a substantial framework in regard of projects. Hence it is recommended to apply the framework in combination with a management tool taking a time aspect into account due to the limited time frame of projects.

Conclusion

Taking an overall view, staging negotiation spaces in project management is about setting the scene, providing objects to get a common understanding of a subject, and iterating with small adjustments. By adding inscriptions the framework is expanded with a strategic dimension and by furthermore seeing spaces as backstage and frontstage a layer of reflection and potential for improvement is applied. By distinguishing between frontstage and backstage, it becomes very clear, that the project team is expected to do some activities to adapt the project to empirical knowledge and data. In this way, users and stakeholders are reflected in solutions, which reinforce sustainable solutions, as the 21st century needs.

A big part of the staging negotiation spaces framework being suitable for project management is the circular approach, which is in accordance with the progressive elaboration needed in every project. Within project management, the framework is valuable in regard to human resource management and project communication management, as the framework mainly involves managing people. This claim comes with some constraints regarding time cost and team composition. It is therefore recommended to combine the framework with a management tool taking time into account and furthermore to work in multidisciplinary teams. If the above is managed, the framework can via its re-framings even become a tool to visualize key findings and how the project has evolves through these (figure 2).

Annotated bibliography

First and foremost it is suggested to read the literature, which seeks to exploit the potential within the theatrical metaphor and expand it to include more than just participatory design. In this sense, the two latter articles are recommended. It is then suggested to dive deeper into different ways of facilitating interaction in a world, which is becoming more and more interactive.

- Brown, N. C. (2020). Design performance and designer preference in an interactive, data-driven conceptual building design scenario. Design Studies. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/340667497_Design_performance_and_designer_preference_in_an_interactive_data-driven_conceptual_building_design_scenario

This article presents a study, where modeling and prediction of performance are being used in live, fast and interactive feedback. This modeling enables the performer to inscribe preferences while accessing performance feedback.

- Pedersen, S. (2020). Staging negotiation spaces: A co-design framework. Design Studies , pp. 58-81. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0142694X20300193

This article is based on the metaphorical notion of staging. To elaborate the applicability of the framework staging negotiation spaces the article analyses the use of stages, negotiations, and re-framings during a co-design process in a large international electronics company.

- Pedersen, S., & Brodersen, S. (2020). Circulating objects between frontstage and backstage: collectively identifying concerns and framing solution spaces. In C. Clausen, V. Dominique, S. Pedersen, & J. Dorland, Staging Collaborative Design and Innovation: An Action-Oriented Participatory Approach (pp. 72-85). Edward Elgar Publishing. https://www.e-elgar.com/shop/gbp/staging-collaborative-design-and-innovation-9781839103421.html

This is a chapter in the book Staging Collaborative Design and Innovation - An Action-Oriented Participatory Approach written by Christian Clausen. The chapter elaborates on the backstage and frontstage activities when investigating a problem. The chapter uses a nice case study to exemplify the framework and circulation of objects.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Elliott et al. (2007). Creating systems that work. London: The Royal Academy of Engineering. https://www.raeng.org.uk/publications/reports/rae-systems-report

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Project Management Institute, Inc. (2000). A guide to the project management body of knowledge (PMBOK Guide). Newtown Square, Pennsylvania, USA: Project Management Institute, Inc. https://caricom.org/wp-content/uploads/PMI_Project_Management_Body_of_Knowledge_Guide.pdf

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 Pedersen, S., & Brodersen, S. (2020). Circulating objects between frontstage and backstage: collectively identifying concerns and framing solution spaces. In C. Clausen, V. Dominique, S. Pedersen, & J. Dorland, Staging Collaborative Design and Innovation: An Action-Oriented Participatory Approach (pp. 72-85). Edward Elgar Publishing. https://www.e-elgar.com/shop/gbp/staging-collaborative-design-and-innovation-9781839103421.html

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Pedersen, S. (2020). Staging negotiation spaces: A co-design framework. Design Studies , pp. 58-81. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0142694X20300193

- ↑ Clausen, C., & Gunn, W. (2016, october 4). From the Social Shaping of Technology to the Staging of Temporary Spaces of Innovation − A Case of Participatory Innovation. Science & Technology Studies , pp. 73-94. https://sciencetechnologystudies.journal.fi/article/view/55358

- ↑ Grönvall, E., Malmborg, L., & Messeter, J. (2016, August 15). Negotiation of values as driver in community-based PD. PDC '16: Proceedings of the 14th Participatory Design Conference: Full papers - Volume 1 , pp. 41-50. https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/2940299.2940308

- ↑ Latour, B. (1999). Pandora's hope: Essays on the reality of science studies (Second printing, 2000 ed.). Harvard University Press. https://monoskop.org/images/c/c1/Latour_Bruno_Pandoras_Hope_Essays_on_the_Reality_of_Science_Studies.pdf

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Akrich, M. (1992). The De-Scription of Technical Objects. In W. E. Bijker, & J. Law, Shaping Technology/Building Society (pp. 205-224). Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press. https://pedropeixotoferreira.files.wordpress.com/2014/03/akrich-the-de-scription-of-technical-objects.pdf

- ↑ Pedersen, S. (2016, august 1). ResearchGate GmbH. Retrieved february 15, 2022 from Navigating prototyping spaces: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/311650075_Navigating_Prototyping_Spaces.

- ↑ Züst, R., & Troxler, P. (2006). No More Muddling Through; Mastering Complex Projects in Engineering and Management. Dordrecht: Springer. https://findit.dtu.dk/en/catalog/2305335675