Stakeholder Engagement and Sustainability in Maritime Spatial Planning

Contents |

Abstract

Maritime Spatial Planning is a fundamental tool for delivering an ecosystem approach and for adding value to existing management measures for the marine environment. From marine and coastal areas to open-ocean regions, Marine Spatial Planning is being developed worldwide to promote sustainable ocean management and governance. In recent years, Marine Spatial Planning has globally widespread and has gained importance in the scientific and policy fields resulting in significant progress by governments [1].

The definition of sustainability was developed in response to stakeholder demands. One of the key mechanisms for engaging stakeholders is sustainability disclosure and how industries and companies approach this matter. Taking into consideration that Marine Spatial Planning plans need to be evaluated periodically, from outcomes to participation processes, and evaluation of these aspects is needed [2].

Therefore, the purpose of this article is to assess the identification and understanding of different stakeholders, their practices, expectations, and interests for economic and environmental resources in Marine Spatial Planning projects, and how the involvement of stakeholders is a key factor for a sustainable successful management regime in the marine environment and marine projects, programs and portfolio. Moreover, the article will focus on different types and stages of stakeholder participation in Marine Spatial Planning processes and the analysis of stakeholders for a sustainable way of stakeholder engagement.

Introduction

Since the decade of the 80s, significant progress has been made by governments in how to face MSP. Nowadays, it is under investigation and development in around 70 countries. These are six continents and four oceans. Despite its acceptance, spread use, development, and implementation of MSP it still faces theoretical and practical challenges

The main questions here are: What is Maritime Spatial Planning? What are its benefits? How is MSP structured?

What is Maritime Spatial Planning?

Maritime Spatial Planning is the process of analyzing and allocating the spatial and temporal distribution of human activities in marine areas to achieve ecological, economic, and social objectives that are usually specified through a political process [3]. In summary, MSP is a way to organize the use of the ocean space and the interactions between and the marine environment. Among these human uses, it is possible to find fisheries, aquaculture, shipping, tourism, renewable energy production, and marine mining. MSP is a continuous process that needs to be regularly funded and adapted to achieve the expected goal and one that requires the engagement of multiple actors and stakeholders at various governmental and societal levels [4] due to the nature of this planning process. The concept of MSP emerged in the context of marine conservation planning, dating back to the 1980s. Some suggest the marine conservation of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park in Australia. However, in the most recent years, there has been a change toward an increasing need to manage conflicting maritime uses [5].

Benefits of Maritime Spatial Planning

MSP focused mainly on the multi-use planning processes whose goal is to integrate and balance economic, social, and environmental objectives for all uses of the ocean. Managing conflicting maritime uses together with conflicts between these uses and marine ecosystems goods and services is exactly why MSP is most needed and a useful tool [6]. MSP is a future-oriented process that can offer many different ways to deal with conflicts and promote compatibilities. When properly developed, MSP can produce a variety of environmental, social, and economic benefits. By reducing use-environment conflicts, MSP promotes efficient use of marine resources and space, as well as the reduction of cumulative human impacts, contributing to preserving marine ecosystem services. Besides, MSP contributes to the allocation of space for marine conservation outcomes, such as marine protected areas. At the social level, MSP improves opportunities for public and stakeholder engagement in ocean use management and it allows for the identification of cultural heritage sites and their protection. At the economic level, the increase of the certainty for private sector investments as well as the transparency in and licensing procedures is seen as one of the main advantages. MSP also identifies compatible human uses within a marine management area and reduces conflicts between incompatible uses [7].

Structure of Maritime Spatial Planning Projects

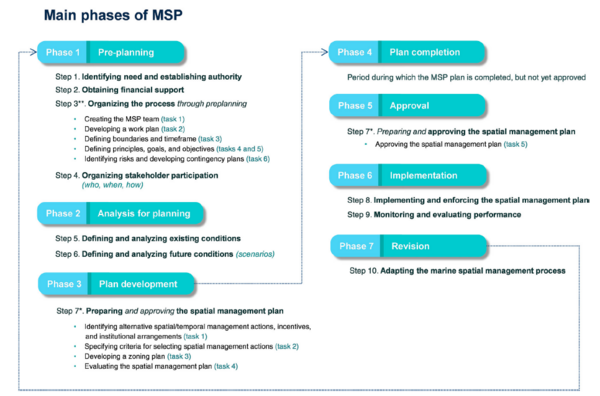

How does Maritime Spatial Planning project function? Different phases need to be fulfilled in an MSP project to ensure its effective development. These phases are:

Preplanning phase (Phase 1): apart from the definition of planning principles, planning goals, and SMART objectives for a particular marine management area, it also involves the identification of boundaries and the need for MSP. This first phase should also include the designation of an appropriate MSP authority responsible for leading the process, the identification of continuing financing mechanisms, the analysis of potential risks, and, the stakeholder engagement in the process [8]. An MSP team should also be assembled and a work plan developed on how to proceed.

Analysis for planning phase (phase 2): this phase carries out the definition and analysis of both present and future conditions such as ecological, oceanographic, or political. It starts with the collection and mapping of data on existing conditions and human activities and the following identification of corresponding conflicts and compatibilities.

Management plan development phase (phase 3). In this phase, management actions are identified to lead to the desired spatial vision for the use of the ocean, and an ocean zoning scheme is developed to support the implementation of these actions [9]. In this phase of MSP, performance criteria, or indicators, should be defined to evaluate the management actions.

The last phases of the process include the management plan completion phase (phase 4), approval of the management plan (phase 5), implementation of the management plan (phase 6) this phase ensures the success of the process and is responsible for entities to ensure compliance with plan’s requirements together with the enforcement of the plan. Finally, the MSP development is finished with the revision of the management plan (phase 7) where results from monitoring and evaluation are used to adapt the elements of the planning process resulting in adaptations and proposals for objectives, strategies, or goals for the following planning process [10].

Stakeholder Engagement in Maritime Spatial Planning

Covering a great number of factors and areas, the development of MSP projects can result in challenges, some of them being more noticeable or widespread. These challenges need to be properly covered so MSP can contribute to sustainable use of the oceans. This article will focus on stakeholder engagement and environmental sustainability considerations given the widespread use of this tool in project management and more specifically in the planning phases since stakeholders are involved in the "purpose" perspective of project management. For a more detailed view on project management structures and perspectives, please refer to Annotated Bibliography.

Stakeholder Engagement

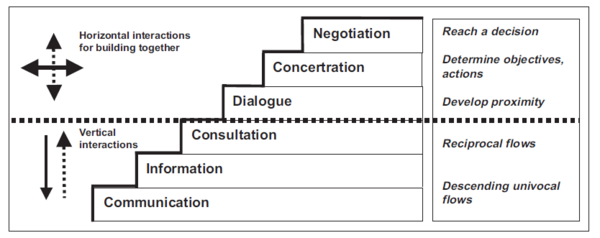

The proper engagement of stakeholders in MSP is fundamental to its adoption and embracement. Accurately reflecting the existing complexity of socio-spatial relationships in a planning area, along with understanding stakeholder practices, expectations, and current and future interests is fundamental to have a balance in economic, social, and environmental objectives in MSP, and to reduce conflicts among ocean users [11]. Factors as poor communication, lack of transparency, the perception that decision-making contributes to the exclusion or nonengagement of stakeholders in MSP as a result of responsible entities not engaging stakeholders at the earliest opportunity, meaning, at the beginning of the whole planning process, promoting the engagement of these stakeholders only at the late stages of development of maritime spatial plans when the proposals and inputs are way less effective. Additionally, most of the time, engagement is limited to public communication, resulting in a lack of more dynamic and proactive approaches such as facilitation and negotiation, where the decision-making process is shared among stakeholders and governments, and usually tend to result in more innovative and lasting solutions [12]. These matters concern the importance of MSP as well as its social equity and legitimacy.

Stakeholder Engagement Process

Once seen these aspects and how stakeholder management in MSP can be a major challenge in its development, an overview of the whole process is given in this section, to clarify the importance of engaging stakeholders to achieve ecological, economic, and social objectives.

Stakeholder participation and involvement are integral to the success of MSP. Increased stakeholder participation and involvement in the resource management decision-making process have acceptance worldwide. There are important reasons why it is important to consider involving stakeholders. Stakeholders generally have a better understanding of the ecosystem, its management, and human influence. Also, an analysis of compatibility/conflicts of objectives is provided through the identification and solution of areas of conflict, resulting in an improvement of interaction. The involvement of stakeholders provides an opportunity to integrate ideas, new options, and solutions and ensure the availability of resources to achieve the objectives. Finally, this can also apport stability in a complex environment and have a sustainable way to move toward ecosystem-based management [13].

Stakeholder Participation

Inside MSP there are different types of potential stakeholders as well as different levels of participation. Stakeholder participation and involvement encourages ownership of the plan and can result in trust among the stakeholders. Here a summarization of the key stages where the public and stakeholders should be encouraged to engage and be involved in the MSP process [14].

• Planning phase: Stakeholders need to be involved in setting priorities, objectives, and purpose of the MSP plan(s). The MSP management team can assist in setting priorities and identifying objectives through stakeholder meetings and group discussions. The main objective is to identify, group, and rank problems, needs, and opportunities in order of priority. This is done through criteria ranking and the result should be made available to the stakeholders for verification.

• Evaluation plan phase: Stakeholders need to be engaged in the evaluation and choice of MSP plan options and the consequences of different approaches on areas of their interest. In developing the plan, tools and methods for participation can be used. Stakeholders have to be clear about the goal and objectives to focus on strategies. The more participatory the process is, the greater the stakeholder acceptance and evaluation of the MSP plan.

• The implementation phase: Stakeholder involvement in applications of MSP and management measures.

• The post-implementation phase: Stakeholder involvement in overall effectiveness evaluation in achieving goals and objectives of MSP plan. An evaluation is undertaken after the implementation of the plan focusing on the analysis of results and stating the achievement of objectives and the impact. The post-evaluation effort should involve all stakeholders to discuss plan results and objectives for the next phase.

For better effectiveness, the stakeholders involved in the process must reflect the complexity in the process. A method that allows this is the use of stakeholder analysis and mapping. In addition to this, need to be empowered to enable a full engagement in the process since participation and empowerment take both time and resources.

Stakeholder Definition

There are uncountable potential stakeholders interested in MSP plans. Among others, these include commercial fishing, recreational fishing, aquaculture, shipping, military, marine protected areas, energy production, and others. Even every individual could be a potential stakeholder. These stakeholders are different depending on their interests concerning marine resources [15]. Not all stakeholders have the same level of interest and may be more or less involved in the MSP process. Stakeholders may also include groups affected by management decisions, groups dependent on the resources to be managed, groups with claims over the area of resources, or groups with activities that impact the area. These groups are usually known as communities.

Importance of Stakeholder Analysis

Stakeholder Analysis is referred to as the procedure for gaining an understanding of a system by identifying the key actors and stakeholders in the system and assessing their respective interests in the system [16].

Stakeholder analysis seeks to differentiate and study stakeholders. Stakeholder groups can be divided into smaller and smaller sub-groups depending upon the particular purpose of stakeholder analysis. The identification of key stakeholders should be inclusive and detailed. The main focus should be on which stakeholders are entitled to take part in discussions and management. For this, some factors have to be considered for stakeholder analysis such as the stakeholders related to the natural resource, the group which they are associated, level of interest, influence, conservation position, and networking

It is important to find out what the interests are after the identification of stakeholder groups the interests and concerns of the stakeholders vary depending on factors like ownership, organization, and values [17].

The broad aspect of stakeholders is important to engage a range of groups and individuals, However, these stakeholders are usually simplified. Stakeholder engagement has to use identification methods by covering the differences among certain groups of stakeholders. As a result, many of them can be overlooked due to the complexity of the process. The differences between them can be assessed taking into consideration some aspects such as existing rights, skills, and relationships for the management of resources, economic, historical, and social reliance on the resources and potential impacts [18].

The stakeholders that meet more criteria are considered primary while secondary stakeholders meet only a few factors. Those who score high on several of these considerations and criteria may be considered ‘primary’ stakeholders. Secondary and tertiary stakeholders may score on only one or two and be involved less significantly. Final stakeholders involved must be well-balanced, however, it is difficult to accomplish this and is often only done by involving other groups and individuals to ensure equal representation in the MSP process.

Limitations and Challenges

Empowerment of Humans as Stakeholders

Participation of stakeholders is critical but not adequate to the MSP process. The empowerment of individuals as stakeholders, using environmental education and social communication, is essential and a pillar of the MSP process. The use of activities to empower people with knowledge and skills can increase their awareness and understanding of the marine environment and management. However, this is a continuing activity and it is important to start these activities as soon as possible, but in practice, this is not done properly and social preparation is lacking. Some activities that could be carried out to improve this in the actual situation include the reduction of social conflict in resources, the introduction of values and changes towards the environment, increasing their visibility and participation in MSP projects as well as to cooperate with primary stakeholders.

Another limitation is the attitude towards changes in the MSP process to be sustainable. Social preparation activities alone will not cause people to change unsustainable practices and behavior. More severe actions are needed such as sanctions for unsustainable activities and changes in the behavior of the different communities. For MSP to be truly sustainable, national planning authorities should consult not only stakeholders but also small groups and individuals on MSP-related matters, and promote movement beyond national MSP initiatives to regional and international ones [19].

Sustainability Considerations

Ensure a balance between socioeconomic development and marine ecosystem conservation has been considered a challenge for MSP. Stakeholder engagement in this aspect is fundamental even though MSP is known as a fundamental process to the sustainable use of the oceans and a practical way to support ecosystem-based management. Lately, little emphasis has been put on sustainability instead of being the foundation on which to build a sustainable future. No attempt is made to address the involvement of stakeholders in ocean management resulting in a limitation of conservation of, for example, marine protected areas. Discussions on the role of marine conservation in MSP are far from being resolved, and the future seems to include using ecosystem services identification and valuation to inform MSP [20].

This is related also to climate change. Climate-related consequences, such as ocean warming, acidification, and sea-level rise, will alter present ocean conditions leading to a redistribution of marine ecosystem goods and services. As a result, the ocean will decrease or increase its offerings and relocation, with potential for new use-use conflicts and increased cumulative environmental impacts. Here is where stakeholder engagement plays an important role, managing and forecasting the use of the ocean with innovative ideas such as the renovation of renewable energy processes and ensuring that activities that rely on the sea as fisheries and aquaculture are affected on the lowest possible level. The planning of changing oceans will not be an easy task. It will require increasingly flexible and adaptive ocean planning approaches and these approaches will most likely be developed by the stakeholders [21].

Annotated Bibliography

The following list provides resources for further research on Maritime Spatial planning and Stakeholder Engagement

- Q. Hanich, PhD / Associate Professor (2008): Marine Policy: Journal

- - Marine Policy is the leading journal of ocean policy studies. It offers researchers, analysts and policy makers a unique combination of analyses in the principal social science disciplines relevant to the formulation of marine policy.

- Charles Ehler and Fanny Douvere (2009): Marine Spatial Planning: A Step-by-step Approach

- - This guide is primarily intended for professionals responsible for the planning and management of marine areas and their resources. It is especially targeted to situations in which time, finances, information and other resources are Iimited.

- J. Chen, B. Glavovic, T. F. Smith (2020): Ocean and Coastal Management

- - Ocean & Coastal Management is the leading international journal dedicated to the study of all aspects of ocean and coastal management from the global to local levels.

- Michele Quesada-Silva,*, Alejandro Iglesias-Campos, Alexander Turra, Juan L. Suárez-de Vivero (2020): Stakeholder Participation Assessment Framework (SPAF): A theory-based strategy to plan and evaluate marine spatial planning participatory processes

- - This study propose an assessment for the analysis of SPAF in order to support assessment of consequences related to the participatory strategies.

- David Christopher Sprengel and Timo Busch (2010): Stakeholder Engagement and Environmental Strategy – the Case of Climate Change

- - This study investigates the role of the sources of stakeholder pressures and additional contextual factors for choosing an environmental strategy.

- Jon Day (2008): The need and practice of monitoring, evaluating and adapting marine planning and management

- - This article discusses key aspects of effective monitoring and evaluation, and summarises lessons learned from over two decades of adaptive management.

- Xander Keijser, Malena Ripken, Igor Mayer and Harald Warmelink (2018): Stakeholder Engagement in Maritime Spatial Planning: The Efficacy of a Serious Game Approach

- - This article covers the complexity of stakeholder engagement in MSP and analyses the diveristy and unfamiliarity of some of these stakeholders with MSP and its potential impact.

- Project Management Institute, Inc. (PMI) (2019): The Standard for Risk Management in Portfolios, Programs, and Projects

- - Risk Management addresses the fact that certain events or conditions—whether expected or unforeseeable during the planning process—may occur with impacts on project, program, and portfolio objectives. Risk Management processes allow for the consideration of events that may or may not happen by describing them in terms of likelihood of occurrence and possible impact.

- Project Management Institute, Inc. (PMI) (2018): Portfolio Management: The standard for portfolio management

- - This book reflects current practices and has been updated to reflect the evolution of the profession.It is a principle-based standard, making it applicable to a broad range of organizations, regardless of project delivery approach.

References

- ↑ https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0308597X0800064X, The importance of marine spatial planning in advancing ecosystem-based sea use management, Fanny Douvere 2008

- ↑ https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0308597X08000675?via%3Dihub, Key elements and steps in the process of developing ecosystem-based marine spatial planning, Paul M. Gilliland 2008

- ↑ https://repository.oceanbestpractices.net/bitstream/handle/11329/204/48.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y, International Workshop on Marine Spatial Planning, Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission 2006

- ↑ https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-319-60156-4, Handbook on Marine Environment Protection, Markus Salomon and Till Markus 2002

- ↑ https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0964569102000522, Zoning—lessons from the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park, Jon Day 2002

- ↑ https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0308597X10001740, Mind the gap: Addressing the shortcomings of marine protected areas through large scale marine spatial planning, Tundi Agardy and Giuseppe Notarbartolo di Sciara 2011

- ↑ https://repository.oceanbestpractices.org/bitstream/handle/11329/459/186559e.pdf?sequence=1, Marine spatial planning: A Step-by-Step Approach, Tundi Agardy and Giuseppe Notarbartolo di Sciara 2011

- ↑ https://repository.oceanbestpractices.org/bitstream/handle/11329/459/186559e.pdf?sequence=1, Marine spatial planning: A Step-by-Step Approach, Tundi Agardy and Giuseppe Notarbartolo di Sciara 2011

- ↑ https://books.google.dk/books?hl=es&lr=&id=F9Kx7y6rKqoC&oi=fnd&pg=PR5&ots=_8DnxQYKtB&sig=vhgMh-vWV_fiPGOv2ZIx_ydSTnE&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false, Ocean Zoning: Making Marine Management More Effective, Tundi Agardy 2010

- ↑ https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0308597X06000765, The role of marine spatial planning in sea use management, F.Douvere, F.Maes, A.Vanhulle and J.Schrijvers 2007

- ↑ https://www.researchgate.net/publication/327039413_Co management_of_natural_resources_organising_negotiating_and_learning-by-doing, Co-management of natural resources : organising, negotiating and learning-by-doing, Grazia Borrini Feyerabend 2000

- ↑ https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0308597X1200019X, Coming to the table: Early stakeholder engagement in marine spatial planning, Morgan Gopnik, Clare Fieseler and Laura Cantral 2012

- ↑ Stakeholder analysis and conflict management, Ramirez R. 2000

- ↑ http://www.abpmer.net/mspp/docs/finals/MSPFinal_report.pdf, Marine Spatial Planning Pilot, Marine Spatial Planning Pilot 2006

- ↑ Strategic management: a stakeholder approach, R. E. Freeman 1984

- ↑ http://www1.worldbank.org/publicsector/anticorrupt/PoliticalEconomy/PDFversion.pdf, Stakeholder Analysis, Jacques Chevalier 2002

- ↑ Stakeholder analysis and conflict management, Ramirez R. 2000

- ↑ Strategic management: a stakeholder approach, R. E. Freeman 1984

- ↑ https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0308597X15003954, Transboundary dimensions of marine spatial planning: Fostering inter-jurisdictional relations and governance, Stephen Jay, Fátima L. Alves, Cathal O'Mahony and María Gómez 2016

- ↑ https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0308597X12001273, The integration of nature conservation into the marine spatial planning process, Kyriazi Zacharoula, Frank Maes and Marijn Rabaut 2013

- ↑ https://www.nature.com/articles/ngeo2821, Ocean planning in a changing climate, Catarina Frazão Santos, Tundi Agardy, Francisco Andrade and Manuel Barange 2016