Stress

Contents |

Abstract

Stress is a feeling of being overwhelmed by events that you cannot seem to control. Stressors are events that cause stress, which can be extreme, uncontrollable and can often produce opposing tendencies. There are four varieties of stress, acute stress, episodic acute stress, traumatic stress and chronic stress. [1] It should not be assumed that stress is always a bad thing. It keeps people motivated and can provide a great sense of achievement once the stressful situation has passed. However, too much stress can have negative impacts. Some people appear to be better at overcoming stressful events, or to view such events as challenges rather than as sources of stress. [2] Worker stress refers to stress that occurs at work and affects work behavior. Strategies for dealing with stress in everyday life may not always be effective in dealing with workplace stress. [3] A project manager must have knowledge about health and wellbeing at workplace such as stress in order to prevent it from becoming a major outbreak to the employees. [4] Workplace stress that project managers need to deal with can be caused by both organizational and individual factors. The stressors in the work environment are the organizational sources, such as demands of performing a job, disagreements with coworkers, and organizational changes. Individual sources are the characteristics of the employee. [3] Many techniques can help to manage stress at work and they can be divided into individual strategies and organizational strategies. Organizational strategies are implemented by organizations or managers with the goal to reduce stress for people at the workplace or in a specific project. Individual strategies are used by employees to reduce or eliminate personal stress. [3]

What is stress?

Stress is a subjective feeling caused by threatening or uncontrollable events. It is critical to recognize that stress does not exist in the situation, it rather exists in how people respond to a specific situation. Hence, when you are stressed, you perceive that the demands of the situation are greater than your ability to deal with them. Your subjective perception of your ability to deal with a given situation may be significantly different from your objective abilities. [1] Stress can have both negative and positive aspects, although it is often seen as an unpleasant state. [3] Negative stress is known as distress, and positive stress is known as eustress. [5]

People are likely familiar with both physiological and psycological reactions to stress. Signs of arousal, such as increased heart rates and respiratory rates, elevated blood pressure, and sweating, are all physiological responses to stress. Anxiety, fear, frustration, and despair are all psychological reactions to distress, as are appraising or evaluating the stressful event and its impact, thinking about the stressful experience, and mentally preparing to take steps to try to deal with the stress. [3]

In order for a person to experience stress, two cognitive events must occur. The first is the primary appraisal, which occurs when a person perceives an event to be a threat to his or her personal goals. The second cognitive event is called secondary appraisal and is when a person concludes that he or she lacks the resources to deal with the demands of the threatening event. Stress is not evoked if either of these appraisals is absent. [6]

Stressors

Stressors are events that cause stress. [1] If an induvidual perceives an environmental event to be dangerous or threatening, it is called a stressor. [3] Some attributes seem to be common with stressors. They are uncontrollable, beyond our ability to influence. Stressors are extreme, causing a state of feeling overloaded or owerwhelmed to the point where one simply cannot take it any longer. Finally, stressors can often produce opposing tendencies, such as wanting and not wanting an activity or object, for example wanting to do a task but also wanting to put it off as long as possible. [1]

People respond to stressors in different ways, some people seem better able to cope and to get over stressful events. The same event can happen to two people, but one is completely overwhelmed and devastated, whereas the other accepts it as a challenge and is motivated into positive action. Differences in how people respond to the same event are possible because stress is in the subjective reaction of the person to potential stressors. [7] We all perceive demands and pressures differently, and we all have different resources or coping skills, which is also referred to as resilience. [1]

Varieties of Stress

Stress is classified into four types by psychologists.

- Acute stress: This type of stress is caused by the sudden onset of demands and is experienced as tension headaches, emotional upsets, gastrointestinal disturbances, feelings of agitation and pressure. Most people associate the term stress with acute stress.

- Episodic acute stress: This type of stress refers to repeated episodes of acute stress so it is more serious. Episodic acute stress can lead to migraines, hypertension, stroke, anxiety, depression or serious gastrointestinal distress.

- Traumatic stress: Refers to a particularly severe case of acute stress, the consequences of which might last for years or even a lifetime. The symptoms with the stress response of traumatic stress is called post-traumatic stress disorder or PTSD. These symptoms are mainly what makes traumatic stress different from acute stress.

- Chronic stress: Another serious form of stress and it refers to stress that does not end. Chronic stress wears us down day after day until our resistance is gone. Chronic stress can lead to serious systemic illness, such as diabetes, decreased immune system functioning or cardiovascular disease. [1]

Worker stress

The stress that occurs at work and affects work behaviour is called worker stress. Strategies used in dealing with stress in everyday life will not always work in dealing with worker stress. For example, some stressors can be eased through organizational changes and thus are under management's control, whereas others must be addressed by the individual worker. Furthermore, some of the techniques for dealing with stress in the workplace are simply good management and human resource practices, not special stress reduction techniques. [3] A project manager must be knowledgeable about stress in order to prevent a problem from spreading to the subordinate workers. [4] Companies and managers are increasingly concerned about the effects of stress on employees and important "bottom-line" variables such as productivity, absenteeism, and turnover. [3]

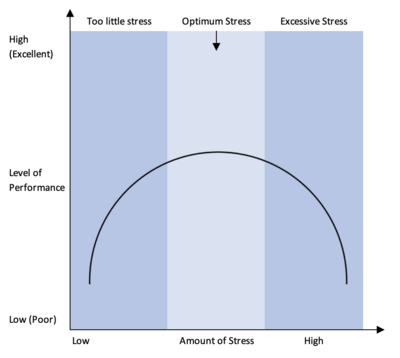

Stress can have an impact on critical work outcomes and is believed to reduce work performance. [3] The relationships between work stress and the key bottom-line variables, on the other hand, are quite complex. It has been proposed, for example, that the relationship between stress and performance often takes the shape of an inverted U (see Figure 1), rather than being direct and linear, with higher stress leading to lower performance. In other words, extremely low and extremely high levels of stress are associated with poor work performance, whereas moderate levels of stress appear to be associated with better performance. [8] For instance, there is evidence that serious, acute stress impairs worker performance because stress interferes with mental processing. [9] On the other hand, a lack of stress indicates that employees are not being challenged or motivated. [10] Stress and job performance are both extremely complex variables, and the inverted U relationship may not apply to all types of stressors or all aspects of job performance. [11]

Why do project managers need to show interest in worker stress?

To begin with, it is important to recognize that a project is a temporary organization formed to deliver one or more business products in accordance with an agreed-upon business case. One characteristic of a project work that distinguishes it from business as usual is that a project involves a group of people with various expertise working together (temporarily) to implement a change that will affect people outside the team. Projects frequently cross the normal functional divisions within an organization and, in some cases, span entire organizations. This frequently results in stresses and strains both within and between organizations. [12]

When stress causes mental strain, feelings of fatigue, anxiety, and/or depression an employees productivity and quality of work can be affected. [3] So, it is important for a project manager to show interest in worker stress and find ways to reduce it, since it can cause illness. [13] Some of those stress-related illnesses are ulcers, hypertension, coronary heart disease, migraines, asthma attacks and colitis. Rates of absenteeism can increase if worker stress leads to stress-related illnesses. That is, if a job becomes too stressful, an employee quits and finds a less stressful position. [3]

Worker stress sources

Sources of worker stress that are common to all kinds of jobs, can be divided into two categories: organizational and individual.

Organizational sources

Stressors in the work environment cause a significant amount of worker stress. The organizational sources of stress can be split into two subcategories. First, the physical and psychological demands of performing a job, the work tasks themselves, such as work overload and underutilization. Secondly, work roles can also cause organizational stress because work organizations are complicated social systems in which a worker must engage with a large number of people. Management actions can often alleviate these two types of situational stressors, work task and work role stressors. Some organizational sources of stress are:

- Work overload: A common source of stress caused by a job that necessitates excessive speed, output, or concentration.

- Underutilization: A source of stress resulting from employees perceptions that their knowledge, skills, or energy are not being fully utilized.

- Job Ambiguity: A source of stress caused by a lack of well-defined jobs and/or work tasks.

- Lack of Control: A sense of having little influence or control over the job and/or work environment. [3]

- Physical Work Conditions: One organizational source of worker stress is the physical circumstances in the workplace. [14]

- Interpersonal Stress: Workplace stress caused by disagreements with coworkers, comes from difficlties in developing and maintaining relationships. [3]

- Harassment: All forms of harassment are extremely stressful, such as sexual harassment, harassment due to gender, race, sexual orientation, and being singled out by an abusive colleague or supervisor. [15]

- Organizational Change: Change is a common source of organizational stress.

- Work–Family Conflict: Buildup of stress that results from responsibilities of work and family roles. [3]

Individual sources

Although factors in the organization or features of jobs and work tasks cause a significant amount of worker stress, some is caused by characteristics of the workers themselves. It is up to the individual worker, not management, to work to reduce these sources of stress. [3] Some individual sources of stress are:

Type A Behaviour Pattern

- Type A personality, or Type A behavior pattern, is distinguished by excessive drive and competitiveness, a sense of urgency and impatience, and underlying hostility. There is evidence that people with the Type A personality are slightly more likely to develop stress-related coronary heart disease, including fatal heart attacks, than people who do not have the behavior pattern, known as Type B. [16]

Susceptibility/Resistance to Stress

- Another source of stress may be that some people are simply more susceptible to stress, whereas others have stress-resistant, hardy personalities. Rather than viewing a stressful situation as a threat, hardy types see it as a challenge and derive meaning from these difficult experiences. [17]

Self-Efficiacy

- Another trait that appears to increase resistance to stress is self-efficacy. Self-efficacy is defined as a person's confidence in his or her ability to take actions that will result in desired outcomes. [18]

Coping with worker stress

The wide amount of strategies and techniques for dealing with work stress can be divided into two general approaches, organizational strategies and individual strategies.

Organizational strategies

Organizational strategies are techniques and programs that are implemented by organizations which have the purpose to reduce stress levels for groups of employees or the organization as a whole. Like stated above, stress can come from many different organizational sources and because of that, there are many things that organizations can do to reduce situational stressors in the workplace. Among these strategies are the following:

Improve the person–job fit

- It can be extremely stressful when there is a mismatch between an employee‘s skills or interests and job requirements. Organizations can alleviate a lot of this stress by maixmizing the person-job fit through the careful screening, selection placement of employees.

Improve employee training and orientation programs

- New employees are usually highly motivated, want to make a good impression by showing that they are hardworking and competent, but they are often the most stressed group in an organization. Their lack of certain job-related skills and knowledge means that they are often not able to perform their jobs as well as they would like. This mismatch between expectations and outcomes can be very stressful for new workers. Therefore, improved employee training and orientation programs could reduce or eliminate stress. [3]

Increase employees’ sense of control

- A lack of control over one's job can be highly stressful. Organizations can alleviate some of this stress by providing workers with a greater feeling of control through participation in work-related decisions, increased responsibility, or increased autonomy and independence. [19]

Eliminate punitive management

- Being threatened or punished at work can be very stressful. When humans are punished or harassed, they react strongly, especially if the punishment or harassment is perceived to be unfair and undeserved. A major source of work stress can be eliminated if organizations reduce or eliminate threatening or punitive company policies. Training supervisors to reduce the use of punishment as a management technique will also help control this common source of stress.

Remove hazardous or dangerous work conditions

- Stress is caused in some occupations by exposure to hazardous work conditions, such as mechanical danger of limb or life loss, health-harming chemicals, excessive fatigue, or extreme temperatures. Another method of dealing with organizational stress is to eliminate or reduce these situations. [3]

Provide a supportive, team-oriented work environment

- There is a lot of evidence that having supportive colleagues—people who can help deal with stressful situations at work—can help reduce worker stress. Workplace social support reduces threat perceptions, reduces the perceived strength of stressors, and improves in coping with work-related stress. The more organizations can foster good interpersonal relationships among coworkers and an integrated, high-functioning work team, the more likely employees will be able to support one another during stressful times. [20] [21] [22]

Improve communication

- Much of the stress at work stems from interpersonal conflicts with supervisors and coworkers. The better the communication among employees, the less stress created by misunderstandings. Furthermore, stress occurs when employees feel disconnected from or uninformed about organizational processes and operations. [3]

Individual strategies

Individual strategies are techniques used by individual employees so personal stress can be reduced or eliminated.

Improvement of physical condition

- This can be done with health programs, such as exercise and diet plans. The primary goal of these programs is to strengthen the body's resistance to stress-related illnesses. It has to be taken into consideration that people will only receive the benefits if they stick to their exercise routines or diet plans.

Relaxation

- Another individual coping strategy is to induce states of relaxation in order to reduce the negative arousal and strain that stress causes. A variety of techniques, including systematic relaxation training, meditation, and biofeedback, have been used to accomplish this. However, there are some disadvantages to these techniques, because most relaxation techniques require a significant amount of dedication and practice, to be effective. [3]

Better and more efficient work methods

- Individual coping strategies may also include a variety of techniques aimed at reducing work stress through better and more efficient work methods. This could for example be a course in time management. Again, similar to the health programs and relaxation techniques, these strategies are dependent on the individual's commitment to the technique as well as his or her willingness and ability to use it on a regular basis. [3] [23]

Removal from a stressful work environment

- People may attempt to cope with stress by removing themselves from a stressful work situation, either temporarily or permanently. It is common for employees to swap a stressful job for a less stressful one. [24]

Cognitive efforts to cope

- Another coping strategy involves cognitive efforts, which may include cognitive restructuring, which entails changing one's perspective on stressors. An example could be when a person is confronted with a stressor, the individual practices thinking neutral or positive thoughts rather than negative thoughts. [25]

Increase employees’ resiliency

- Individual differences in stress resilience have resulted in programs designed to increase employees' resiliency. These programs take various forms, but many of them include some form of cognitive training, such as mindfulness training, emotional awareness and regulation, and developing a sense of self-efficacy. [3]

Annotated bibliography

The following resources are the key resources used for this article, and can provide basis for further and deeper studies on the topic.

Larsen, R. J., & Buss, D. M. (2017). Personality psychology: Domains of knowledge about human nature (6th edition). McGraw-Hill Education.

The book covers a wide range of topics in personality psychology. Chapter 18 – Stress, Coping, Adjustment and Health, focuses on the aspect of personality psychology that is concerned with physical adjustment and health. The concept of stress is observed, for example stress responses and how personality can affect how a person responses to stress.

Riggio, R. E. (2018). Introduction to Industrial / Organizational Psychology (7th edition). Routledge.

This book takes an approach to psychological theory and its applications in the workplace. Chapter 10 – Worker Stress and Negative Employee Attitudes and Behaviours, primarily deals with worker stress, workplace stress that has an impact on employee behaviour. It gives guidance for organizations, managers and individuals on how to reduce or eliminate stress at the workplace.

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal and coping. New York: Springer.

The book goes into details about theory of psychological stress, based on the concepts of cognitive appraisal and coping. This book compiles two decades of research and thought on topics such as behavioural medicine, emotion, stress management, treatment, and life span development.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Larsen, R. J., & Buss, D. M. (2017). Personality psychology: Domains of knowledge about human nature (6th edition). McGraw-Hill Education.

- ↑ Aranđelović, M., & Ilić, I. (2006). STRESS IN WORKPLACE - POSSIBLE PREVENTION. Medicine and Biology, 13(3), 139 - 144.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 3.16 3.17 3.18 3.19 3.20 Riggio, R. E. (2018). Introduction to Industrial / Organizational Psychology (7th edition). Routledge.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Abdul Rahim Abdul Hamid A. R. A, Singh B. & Arzmi A. B (2014). Construction Project Manager Ways to Cope With Stress at Workplace. doi:10.13140/2.1.3256.0966

- ↑ Golembiewski, R. T., Munzenrider, R. F., & Stevenson, J. G. (1986). Stress in organizations: Toward a phase model of burnout. New York: Praeger.

- ↑ Lazarus, R. S. (1991). Emotion and adaptation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal and coping. New York: Springer.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Cohen, S. (1980). Aftereffects of stress on human behavior and social behavior: A review of research and theory. Psychological Bulletin, 88, 82–108. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.88.1.82

- ↑ Ellis, A. P. J. (2006). System breakdown: The role of mental models and transactive memory in the relationship between acute stress and team performance. Academy of Management Journal, 49(3), 576–589. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMJ.2006.21794674

- ↑ LePine, J. A., Podsakoff, N. A., & LePine, M. A. (2005). A meta-analytic test of the challenge stressor-hindrance stressor framework: An explanation for inconsistent relationships among stressors and performance. Academy of Management Journal, 48(5), 764–775.

- ↑ Beehr, T. A. (1985). Organizational stress and employee effectiveness: A job characteristics approach. In T. A. Beehr & R. S. Bhagat (Eds.), Human stress and cognition in organizations: An integrated perspective (pp. 57–81). New York: Wiley.

- ↑ Managing Successful Projects with PRINCE2. (2017). Managing Successful Projects With Prince2. TSO.

- ↑ Ganster, D. C., & Rosen, C. C. (2013). Work Stress and Employee Health. Journal of Management, 39(5), 1085–1122. doi:10.1177/0149206313475815

- ↑ Frese, M., & Zapf, D. (1988). Methodological issues in the study of work stress: Objective vs. subjective measurement of work stress and the question of longitudinal studies. In C. L. Cooper & R. Payne (Eds.), Courses, coping and consequences of stress at work (pp. 375–411). New York: Wiley. Retrieved March 4, 2022, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/322163405_Frese_M_Zapf_D_1988_Methodological_issues_in_the_study_of_work_stress_In_CL_Cooper_R_Payne_Eds_Causes_coping_and_consequences_of_stress_at_work_pp_375-411_Chichester_Wiley

- ↑ Raver, J. L., & Nishii, L. H. (2010). Once, twice, or three times as harmful? Ethnic harassment, gender harassment, and generalized workplace harassment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(2), 236–254. Retrieved March 4, 2022, from https://doi.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2Fa0018377

- ↑ Schaubroeck, J., Ganster, D. C., & Kemmerer, B. E. (1994). Job complexity, ‘type A’ behavior, and cardiovascular disorder: A prospective study. Academy of Management Journal, 37, 426–439. Retrieved March 4, 2022, from https://doi.org/10.2307/256837

- ↑ Britt, T. W., Adler, A. B., & Bartone, P. T. (2001). Deriving benefits from stressful events: The role of engagement in meaningful work and hardiness. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 6, 53–63. Retrieved March 4, 2022, from https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.6.1.53

- ↑ Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. San Francisco, CA: W. H. Freeman.

- ↑ Ganster, D. C., Fox, M. L., & Dwyer, D. J. (2001). Explaining employees’ health care costs: A prospective examination of stressful job demands, personal control, and physiological reactivity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 954–964. Retrieved March 4, 2022, from https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.5.954

- ↑ Fenlason, K. J., & Beehr, T. A. (1994). Social support and occupational stress: Effects of talking to others. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 15, 157–175. Retrieved March 11, 2022, from https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030150205

- ↑ Viswesvaran, C., Sanchez, J. I., & Fisher, J. (1999). The role of social support in the process of work stress: A meta-analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 54, 314–334. Retrieved March 11, 2022, from https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1998.1661

- ↑ Unden, A. (1996). Social support at work and its relationship to absenteeism. Work & Stress, 10, 46–61. Retrieved March 11, 2022, from https://doi.org/10.1080/02678379608256784

- ↑ Shahani, C., Weiner, R., & Streit, M. K. (1993). An investigation of the dispositional nature of the time management construct. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 6, 231–243. Retrieved March 11, 2022, from https://doi.org/10.1080/10615809308248382

- ↑ Fritz, C., Ellis, A. M., Demsky, C. A., Lin, B. C., & Guros, F. (2013). Embracing work breaks: Recovering from work stress. Organizational Dynamics, 42, 274–280. Retrieved March 12, 2022, from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2013.07.005

- ↑ Lazarus, R. S. (1991). Psychological stress in the workplace. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 6, 1–13.