Task Interdependecies in Projects

Abstract

A project consists of a series of tasks that need to be executed in order to complete it. The way these tasks are arranged in relation to each other will come down to their interdependence. According to James D. Thompson, task interdependence can be distinguished into three types: pooled, sequential and reciprocal. For a project manager interdependencies can be a powerful tool in managing the complexity of a project. Using interdependencies to characterize tasks in a project will help to determine the sequence of which tasks should be completed in order to optimise time use, resources, workers, etc. As the original classification of the three interdependency types, by Thompson, is quite old, additions to the terminology has been added over the years. Especially noteworthy here is the addition of intensive interdependecy. As the categorization of task interdependecies in and of itself is not particularly useful, the types are accompanied by three coordination types: standardization, planning, and mutual adjustment. These help guide the project manager through how to best address the interdependencies that they identify in their project's tasks. Lastly, it should be noted that task interdependencies are not perfect and they need to be used in conjunction with other tools to realize their potential. They should not be seen as an "easy way out" in terms of managing project complexities, as they are only as useful as the capabilities of the project manager allows them to be. All this will be explained in greater detail in the article.

Contents |

Big Idea

Complexity

A project consists of a series of interdependent tasks. These need to be completed in a certain manner which is determined by each task’s link(s) to other tasks. In this way, a project can be seen as a dynamic system where factors such as the number of tasks, their interconnectivity, uncertainty, ambiguity, and many more, makes up a projects degree of complexity.[1][2] A Project Managers ability to manage this complexity, in any variable shape or form it might take, is crucial for a projects chance of success. Tools that help deal with the different factors of complexity are therefore important for Project Managers to know about.

One such tool is the three types of interdependence, defined by J.D. Thompson in 1967.

Purpose

With projects of high complexity, where risk of internal conflict and breakdowns is increased[3], the potential impact of using interdependency management is increased as well. Managing a project is a constant battle in taming the process and maintaining control of it[4]. Understanding interdependencies within a project and being able to manage them appropriately is , therefore, a powerful tool for any project manager, as it addresses the inherent uncertainties that is found in any project[5], and thereby also addresses the complexity of it. Managing interdependencies between tasks, provides the project manager with overview of the processes that are to be performed in a given project, and gives them the power to distribute and manage resources within the project team strategically, both before and during the run of a project.

J.D. Thompson and Organizations in Action

While J.D. Thompson’s original theory on pooled, sequential and reciprocal interdependency were targeted organisational structures, the theory can be applied to any type of “body” that consists of interconnected elements and tasks, such as projects, programs and portfolios. For the sake of the course and to ensure high relevancy to the reader, the theory will be applied to a project level instead of organisational structures.

Types of interdependencies

As described in the ”Complexity” section, projects consists of a number of tasks with varying degrees of interdependence between each other. This does not entail that all tasks are directly connected. What is meant by interdependence is that all tasks in a project works towards a common objective[8] and if one task fails it might impact the chances of success for that objective, thereby impacting all tasks connected to it[6].

For a project manager it is necessary to be able to address these interdependencies and use them to structure the tasks of a project. First step towards this is being able to distinguish and identify different types of interdependencies, and subsequently know how to handle tasks depending on which type they are. In 1967, J.D. Thompson defined three types of interdependencies that each operates on a contingency level above the previous[6]. These will be further described in the sections below. As it has been quite a while since the J.D. Thompsons original theory was published for the first time, the field of interdependence has been expanded upon. Some of these additions to the theory will also be described.

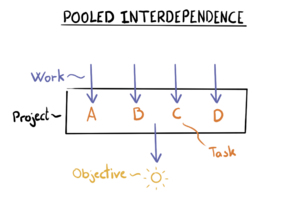

Pooled interdependency

Of the three types of interdependencies that J.D. Thompson defines, pooled interdependence is the simplest. When a project contains a series of tasks of which non of them are directly connected or dependent on each other, these tasks are still working towards a common deliverable. Therefore, each of the tasks are still indirectly dependent on that the other tasks are completed, as the projects end deliverable will not be achieved otherwise. Each task works independently on a discrete contribution that helps in completing a common goal as visualised on Fig. 1.[6]

An example of an interdependency like this in a project, could be in a construction project, where the objective is to complete a specific structure. This structure consists of various parts that is being worked on by different teams with different capabilities. All teams work towards completing their own task, but are at the same time, dependent on every other team doing so as well in order to achieve the end goal of finishing the construction.

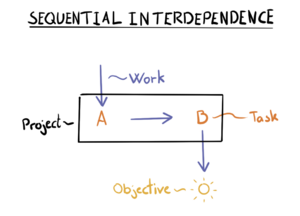

Sequential interdependency

The second type of interdependency identified by Thompson is referred to as sequential interdependency. In this definition, a task within a project is dependent on the output from the completion of a previous task before it itself can be executed. This creates an interdependent relationship between them where it is necessary for tasks to be completed in a specific order to achieve a common objective, as seen on Fig. 2. Both tasks in this relationship are still dependent on the completion of the other to fulfill the end objective, which entails that pooled interdependency inherently exists as a part of this setup.[6]

Using the same construction setting as for the previous example, sequential interdependency can occur here too. Some parts of a construction project need to be completed before another can be begin. An obvious example of this is the windows of a house, that are dependent on the walls to be built before they can be installed.

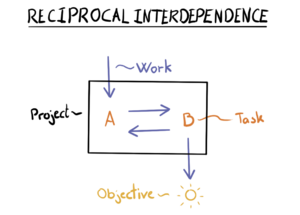

Reciprocal interdependency

The third and final interdependency type that Thompson describes is reciprocal interdependency. The tasks seen in this type of interdependency are characterized by high contingency between each other. With this setup, a set of tasks takes the output of the other tasks as input, creating a type of looping process of dependency between the tasks, that is needed to complete the common objective. See Fig. 3 for a visualized representation of this. Often, an objective connected to such a setup is one that runs continuously throughout a project. This is the most complex of the three interdependency types, and exactly as it was seen with sequential interdependency, the less complex interdependency types can both be located within this one. Sequential interdependence exists as the output dependence from other tasks and in thereby as aforementioned, pooled interdependency lies within as well.[6]

Here, the construction project can be used once again as an example. For a multistorey building the team that is placing the walls are dependent on the team that is laying the floor to be completed. Subsequently, the floor team is dependent on the wall team before they can continue on the following floor. Another example is the relationship between the design team of a construction project, and the engineering team. The engineering team is dependent on the design developed by the design team. In turn, the design team is dependent on the feedback from the engineering team in regards to changes of the project, like fulfilling regulations or change in scope from the client.

Summary

According to Thompson, the three types of interdependencies represent three degrees of complexity that a project can contain, distributed in a hierarchical order. Least complex is pooled interdependency, followed by sequential interdependency, with reciprocal interdependency being the most complex of the three. In this hierarchy, an interdependence with higher complexity will always contain the interdependencies with lower complexity, but not the other way around. This means, that if reciprocal interdependence is identified within a project, it is safe to assume that this project also has sequential interdependency and pooled interdependency. On the other hand, if pooled interdependency is identified within a project, it cannot be assumed that the project contains any of the other interdependency types.[6]

Inherently, this allows the presence of each type of interdependency to be used as a way to determine the complexity of a project. However, this should not be done without caution, cause while the presence of pooled interdependency cannot be used to identify interdependencies of higher complexity, it cannot rule out their presence either.

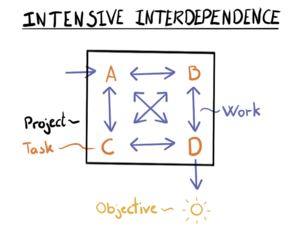

Other interdependencies (Intensive interdependency)

While Thompsons three original types of interdependencies have stood the test of time, they have not been without scrutiny. A common point of critique has been questioning the original types’ ability to sufficiently cover and explain all sorts of organizations, as some would argue that some structures are not able to be defined through these. When the focus is shifted onto projects, as this article does, this lack of depth becomes even more apparent.

To address this critique, a fourth type of interdependency was introduced by Van de Ven, Delbecq, and Koenig in 1976[7], named intensive interdependency. In relation to the complexity hierarchy, it lies a step above reciprocal interdependency, but works in a different way than the others. Work that is categorized as intensive does not have a clear distinction to the order of input or output between tasks, which is evidently apparent in the original three types. Instead, completing intensive work is characterized by a workflow where tasks are worked upon simultaneously by multiple entities and without a specific order or sequence dictating it (see Fig. 4).

A number of other types of interdependencies exists including Risk Interdependency, Resource Interdependency, and Outcome Interdependency. While these are recognized in literature ([9], [10][11], [12]), they all also use principles from the original task interdependencies defined by Thompson, while of course being tailored towards specific use cases. As they are not within the scope of this article, they will not be dived further into in this article.

Coordination

Along with the categorization of the three interdependencies, and their individual characteristics, Thompson included a set of ways on how to manage each of the interdependency types. These coordination types, paraphrased from the work of March and Simon (1958)[13] follow the principle mentioned previously, that with the rising complexity within the hierarchy of the interdependency types, a rise in management cost will inherently follow, as they, with higher contingency, also are more difficult to coordinate[6].

Standardization

The first type of coordination, standardization, entails the creation of routines and rules into a workflow. These initiatives intent to restrain and streamline work processes so that they are aligned across the project team. This is done to increase work efficiency and mitigate risks of communication issues between team members. To do so it is integral to ensure that rules are consistent between interdependent tasks. Additionally, rules for standardization of work processes should be simple enough to be applicable in settings with different characteristics, as work might require interdependent tasks to be performed in different team settings for completion. Thompson connects this coordination type with pooled interdependency, as the parallel work process of this interdependency type complements the benefits of applying structure and rules to tasks to ensure compatible outputs.[6]

Planning

With this type of coordination comes the creation of schedules across interdependent teams. These are made to align and time team objectives and subsequent tasks, as a way to derive the appropriate course of action. The schedule is by nature, less confined in its influence over a project, as it does not directly dictate the work process, but rather demarcates the parameters necessary to coordinate tasks and task output to facilitate effective collaboration across a project team. This coordination type is connected to sequential interdependency by Thompson as it fits well with the sequential characteristic of output dependency that is inherent to it. In essence, it makes sense to plan out the time that one task output must be produced to allow its recipient to prepare and be ready to receive it.[6]

Mutual adjustment

The final coordination type explains the necessity of communication between team members. What it means is that the transfer of information between a team, within a project is integral to its function. Mutual adjustment is the least confined of the three, as it is meant to be the one that is the most flexible and thereby be applicable to a larger number of variables and uncertainties. This is also why Thompson connects it to reciprocal interdependency, as well as Intensive Interdependency, because they are interdependencies with a large amount contingency associated with them.[6]

Application

Utilizing interdependencies

In general, it is understood that to be able to handle interdependencies it is necessary to understand them[4]. The aim of this article, so far, has been to provide the necessary foundational information that should ensure a general understanding of task interdependencies within a project context. In order to successfully apply this situation in a real-life project context, the following section will look at ways to address interdependencies when they have been identified.

As projects are complex by nature, task interdependencies can only provide a part of the overall picture which is necessary for keeping the overview and address uncertainties. The identification of task interdependencies by itself is, therefore, not an effective way of utilizing their potential. The identification, however, can be used as a foundation for a larger initiative in an effort to make strategic decisions in a project. This foundation can further benefit from the inclusion of models like the Project Management Triangle ([1], [1]) or the Iron triangle, as it is also called, as a complimentary tool that can help project managers navigate and guide decisions making. The initiative should then subsequently be reinforced with tools that correspond to the identified interdependencies, which the coordination types can help with.

Tasks identified to have pooled interdependency between each other will implement rules and routines, following the standardization coordination type. The rules and routines are meant to mitigate the risk of miscommunication between task-holders, and at the same time minimize the need for communication by setting a shared set of standards to follow. This will be done by management, possibly with guidance from specialist to ensure the established guidelines does not compromise the end product, and that potential regulations and legislations are met.

A project containing tasks identified with sequential interdependency will, following the coordination types, structure these tasks using planning coordination. A tool that can be used to facilitate planning coordination is the Gant chart, as it is designed to keep track of linear processes that have an end to them[4]. This interdependency type is relatively simple to handle as the flow of the tasks and task output follows a linear path, and it is therefore possible to easily locate bottlenecks, and trace back responsibility through the path of tasks[4].

For reciprocal and intensive interdependency, the same coordination type applies, mutual adjustment, and they are therefore addressed in similar ways. Tasks with these interdependencies between each other, rely on continuous communication and information exchange between the task holders. This communication can be achieved with general tools such as status meetings[2], e-mail correspondence, and Kanban boards or with more sophisticated tools such as a Project Communication Plan[3], and PM tools e.g., the monday.com platform and Miro.

Limitations

While knowing how to address and work with task interdependencies within a project can be a helpful management tool that can help reduce project complexity and mitigate the risks from project uncertainties, their implementation comes with potential ramifications. Firstly, the process of using task interdependencies actively in a project entails substantial work and planning on its own. The identification process will increase in workload with the complexity of a project and might therefore add additional work hours for a project manager. Furthermore, the planning that the coordination types encourage might result in a lack of flexibility in the project, possibly leading to unforeseen consequences, should a unknown risk occur[4]. Communication, that is essential to the reciprocal and intensive interdependency, can also fail resulting in subpar results, delays, etc.

However, while the identification of interdependencies might require extra work hours, doing so will also provide the project manager with a better overview of the given project and more control over possible risks. Risks that are tied with uncertainties that would otherwise be ignored or dealt with if/when they occur, possibly increasing their negative impact compared to the time invested in preventing them. The rest of the ramifications, could be said, are not the fault of the interdependency types per se, but rather a possible outcome that could happen whether the interdependencies were addressed or not. If anything, they highlight places where problems could arise during the project and allows for preventative measure to be taken beforehand.

Additional reading

Interdependency management in project portfolio management

For the curious reader that want to dive deeper into the project portfolio management part of interdependencies, the following sources display a method for visualizing interdependencies between projects in a portfolio, also in an effort to make better strategic management decisions. The first source is about developing the project network visualization. The second source builds upon this methodology to develop a method for quantifying the individual interdependencies between projects to provide even more detailed information.

- Bilgin, G., Eken, G., Ozyurt, B., Dikmen, I., Birgonul, M.T., et al. (2017a) ‘Handling project dependencies in portfolio management’, Procedia Computer Science, 121, pp. 356–363. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2017.11.048.

- Killen, C.P. and Kjaer, C. (2012) ‘Understanding project interdependencies: The role of visual representation, culture and process’, International Journal of Project Management, 30(5), pp. 554–566. doi:10.1016/j.ijproman.2012.01.018.

Annotated Bibliography

Knotten, V., Svalestuen, F., Hansen, G. K., & Lædre, O. (2015). Design management in the building process - A review of current literature. Procedia Economics and Finance, 21, 120–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2212-5671(15)00158-6

The article seeks to address a falling productivity in the AEC industry and looks to task interdependencies from a design management point of view. The articles take on the interdependency types have been a key part of providing an understanding of the utilization of interdependencies in a modern context, adding theory on project complexity and uncertainties to improve this perspective.

Mach, M., C.M. Abrantes, A., & Soler, C. (2021). Teamwork in Healthcare Management. IntechOpen. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.96826

The article uses task interdependence in teams from a healthcare context. It has been valuable in its explanation of the four interdependency types that are used in this article.

Thompson, J. D. (1973). Organizations in action: Social science bases of administrative theory. McGraw-Hill.

This is the book that lays ground to the theory of this article. While Thompson’s classification of task interdependencies is not the only, or even the first, effort to explain and structure them, his work has proved influential in different industry settings, and is still in use today. The original book is therefore still relevant when learning about interdependencies to this day.,,

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Geraldi, J., Thuesen, C., Oehmen, J., & Stingl, V. (2017). Doing Projects. A Nordic Flavour to Managing Projects: DS-handbook 185:2017. Dansk Standard.

- ↑ Project Management Institute, Inc. (PMI). (2017). Standard for Program Management (4th Edition) - 2.5.3 Complexity. Project Management Institute, Inc. (PMI). Retrieved from https://app.knovel.com/hotlink/pdf/id:kt012S0SG1/standard-program-management/complexity

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Mach, M., C.M. Abrantes, A., & Soler, C. (2021). Teamwork in Healthcare Management. IntechOpen. doi: 10.5772/intechopen.96826

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Knotten, V., Svalestuen, F., Hansen, G. K., & Lædre, O. (2015). Design management in the building process - A review of current literature. Procedia Economics and Finance, 21, 120–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2212-5671(15)00158-6

- ↑ Project Management Institute, Inc. (PMI). (2021). A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK ® Guide) – 7th Edition and The Standard for Project Management - 2.8.1 General Uncertainty. Project Management Institute, Inc. (PMI). Retrieved from https://app.knovel.com/hotlink/pdf/id:kt012LZJ23/guide-project-management/general-uncertainty

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 6.12 Thompson, J. D. (1973). Organizations in action: Social science bases of administrative theory. McGraw-Hill.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Ven, A. H., Delbecq, A. L., & Koenig, R. (1976). Determinants of coordination modes within organizations. American Sociological Review, 41(2), 322–338. https://doi.org/10.2307/2094477

- ↑ International Organization for Standardization & Dansk Standard. (2021). Project, programme and portfolio management – Context and concepts (Standard No. 21500). Retrieved from https://sd.ds.dk/Viewer?ProjectNr=M351701&Status=60.60&Inline=true&Page=1&VariantID=41

- ↑ WIRBA, E. N., TAH, J. H. M., & HOWES, R. (1996). Risk interdependencies and natural language computations. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, 3(4), 251–269. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb021034

- ↑ Tilk, C., Drexl, M., & Irnich, S. (2019). Nested branch-and-price-and-cut for vehicle routing problems with multiple resource interdependencies. European Journal of Operational Research, 276(2), 549–565. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2019.01.041

- ↑ Project Management Institute, Inc. (PMI). (2017). Standard for Program Management (4th Edition) - 8.2.7.1 Resource Interdependency Management. Project Management Institute, Inc. (PMI). Retrieved from https://app.knovel.com/hotlink/pdf/id:kt012S0VU1/standard-program-management/resource-interdependency

- ↑ McLaughlin, D. M. (2023). Evaluating the impact of different spatial linkages on forum outcome interdependencies in Polycentric Systems. Public Administration Review, 83(3), 552–569. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13599

- ↑ March, J. G., Guetzkow, H. S., & Simon, H. A. (1958). Organizations. by J.G. March and H.A. Simon with the collaboration of Harold Guetzkow. with a bibliography. New York; Chapman & Hall: London.