Tuckmans model for Team Development

Developed by Moritz Rindermann

In every project the executing team plays an important role. In 1965, the American psychologist Bruce Tuckman introduced his model for group development. This model consists of 4 stages: Forming, Storming, Norming and Performing. Tuckman suggested that teams will need to go through those stages within a project to grow together and be successful. [1]. With his ideas, Tuckman set the basis for the research on group development and the related activities and processes. [2]

According to the inventor, every phase is defined by certain characteristics and a set of activities that should be performed in order to move on. [3] The project managers, who are responsible for guidance, group development and eventually the success of the project itself, therefore play a major role within the process. They have to ensure that the team overcomes the challenges and clear the stages. [4].

The Forming phase is characterised by orientation. The group members get to know each other, set goals, a timeline, and a structure. In the Storming stage first problems appear and frustration levels increase. The Norming phase then overlaps with the previous Storming stage. Within this phase, group members become aware of their peers’ strengths and start to value them. Productivity levels typically rise during Norming. Performing is the last of the 4 initial stages. It is about facing the challenges of the project and performing the actual tasks. [1]

Even though Tuckman’s model of group development certainly has evolved over time, it is still relevant today [3]. However, it has been subject to various changes and additions over the last decades. This article will focus especially on those adaptations, explain the differences, as well as application possibilities and the role of the project manager within team development.

Contents |

Importance of Team Development

A team is defined by "two or more individuals, interacting and interdependent, who have come together to achieve a particular objective" [5] (p. 18). It shows that the team is on of the core elements of a project. It is needed to execute and work towards the goals. Team development therefore plays an important role in the context of project management. In 2015 Decuyper et. al described a clear relationship between team development and group learning. According to them, a team that evovles through the first stages can unlock synergies and has a better learning curve. Especially in the later phases of the development process, groups can expect better results. [6] This means that successful team development can be a major factor for the actual performance of the group.

Within this process, project managers have a special role in the project team. They are responsible for their team and for the project and "need to take a holistic view of their team’s products in order to plan, coordinate, and complete them." [4] (p. 51). Managing complexity is a key task of project managers and part of this complexity is the human behaviour that happens inside a the team. [4] Neumann and Wright underline this connection with the discovery that interpersonal skills have a direct effect on team effectiveness. [7] It is therefore the project manager's responsibility to develop those skills within their team.

Tuckman's basic Model

Bruce W. Tuckman introduced his model for team development in his article "Developmental Sequence in Small Groups" published in the Psychological Bulletin in 1965. While all groups are individual and unique, the model consists of four stages that newly created groups typically go through. [8] The stages are called Forming, Storming, Norming, and Performing (see Figure 1). All of those have certain characteristics, challenges and tasks. How well a group can manage these challenges can determine the success and the efficiency of the project. [1] One of the main tasks of the project manager is to perform integration and manage complexity. Therefore, the project manager plays a vital role in this environment by guiding and leading the team throughout the stages. [4]

Forming

The first stage in Tuckman's model is called Forming, which marks the start of the development of a team. Forming is characterized by orientation and uncertainty. The members do not fully know the task and the other members at this point. The key in this stage is therefore to identify the assignment and the challenges, as well as set up guidelines and boundaries for the group. Within the orientation process, both interpersonal, as well as professional and task-related acclimatization occurrs to familiriaze with group and project. [1] Tuckman described this by identifying the "relevant parameters and the manner in which the group experience will be used to accomplish the task" [1] (p. 386). He also reffered to the group structure as Testing and Dependance, which highlights the orientational character of this early phase. [1] The expectations are typically high in the stage, because the team members have a positive mindset. [9] [2] During the Forming the performance level is usually low, because the main focus is establishing the group. [10]

Storming

The second stage is called Storming. At this point in time, the first problems arrise within the group. Tuckman also labelled this phase as Intragroup Conflict. The key aspects are centered around personality issues and emotional responses. Team members usually take on different opinions about the future process of the group and develop personal issues. Typically, hierarchies develop within this phase as a natural process. The root cause of the ocurring problems lies partly within the uncertainty already described in phase 1. [1] However, it is not only uncertainty about one's role in the project, but also the "progression into the unknown" [1] (p.386) as Tuckman describes it. The high degree of uncertainty and the discrepancy between self-awareness and role and task are also drivers of conflicts. Individuality and the pressure to change according to the tasks assigned can often result in anger and depression on an emotional level. Consequently, the performance is at a low point during Storming. [9] [2] Conflict is an important part in the development process, because it can lead to a loss of focus on the goals and cause delays and disruption. [11]

Norming

After the disharmony of the Storming, the team develops a sense of unity in Norming. Group Cohesion as it was called by Tuckman is reached by a common goal that the team members are persuing. In order to increase the performance and reach their objectives, the participants agree on norms and set up roles within the group. Personal discrepancies are put aside to ensure a succesful operation and therefore hostility displaces the perviously tense and emotional atmosphere. Opinions are exchanged, but alternative ideas are considered and evaluated without emotions to ensure a smooth execution of the project. Tuckman describes that "the group becomes a simulation of the family constellation" [1] (p. 389). The performance level typically rises within the Norming as a result of the common understanding and harmony. [2] [9]

Performing

The last of Tuckman's initial four stages is called Performing and the group structure is characterized by Functional Role-Relatedness. The phase is best described as a mixture between functionality and professionality. The team members have found their roles within the group and execute them according to their individual tasks, which leads to improved performance. It is essential that the participants provide support for each other, especially in a professional, work-related level to help others succesfully execute their jobs. Tuckman describes that "The group, which was established as an entity during the preceding phase, can now become a problem-solving instrument"[1] (p.387), which means that the team itself now becomes a tool for project management. The structure of the group is a performance-enhancing factor in which roles are defined, but flexible. The team members focus solely on the execution of the task without interpersonal dirsuptions. [1] [9] [2]

Application

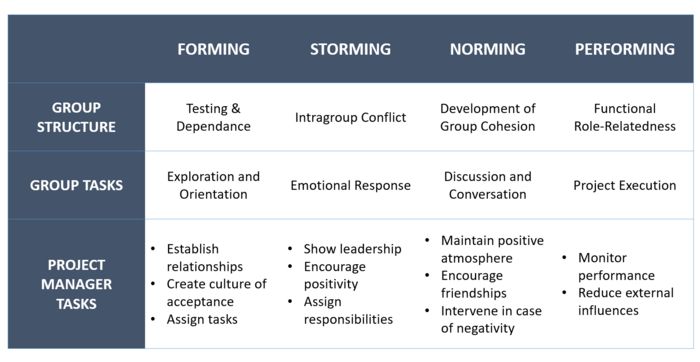

Since Tuckman’s model is more of a theory than a project management tool, there is no clear guide of application. Every team goes through a development process thoughout its life cycle. However, guiding this development is important to ensure better cooperation and a smoother execution. Tang describes this relationship by stating "Conscious attention to structure and roles can make an enormous difference in team performance" [12] (p. 39). Therefore, some recommendations can be derived from Tuckman's model in order to ensure a successful process in practice. These application tipps include two levels: Group activities and the role of the project manager.

Forming: Team members in this stage have to explore and orientate. The main activity for project managers on a social level is to establish relationships with the single members and form a culture of acceptance and creativity in the group. They also need to identify professional strengths and skills of their team members in order to be able to assign tasks in the further process. As a leader the project manager has to set boundaries and create a professional atmosphere. [14]

Storming: Team members typically respond emotionally in this stage, especially towards change and cristicism. This resistance against the team structure is normal in the development, but needs to be adressed. The project manager has therefore an important role in the Storming phase. He needs to show strong leadership and answer with positivity to the emotional conflicts. Another part of his job is to match the people and their respective roles within the organization. This can already solve conflicts by setting responsibilities. [14]

Norming: Team members are engaging in discussion and conversion within the Norming stage. This can be about oneself, the own role or the project in general. Project managers should seek to maintain the positivity in this stage and encourage their team members to form bonds and friendships, as well as increase communication and interaction. In case negative feelings or issues appear, the project manager should intervene immediately to ensure the success of the project. [14]

Performing: The group members work towards their goal in this stage. The group activity is therefore to create insight, analyze the situation and the data and execute their given tasks. Creating Emotional Intelligence is the key to even higher efficiency and productivity. This means that the team members work as one entity and establish complete trust as a basis of their work. The project manager has to monitor the group and its performance in this phase, be aware of negative influences and otherwise try to reduce external influences. The team should execute the project naturally and with as few interventions as possible. [14]

Apart from the tasks in each of the phases, there are certain characteristics and behaviours that project managers should always try to aim for. Some of them like leadership or creating a postitive culture are more intuitive. The best approach to leading the team is also dependend on the circumstances, team memebers and other factors. Therfore, the managers should always "have a flexible approach to group development and should keep attuned to the different needs and requirements of groups at the various stages." [8] (p. 377). This means that generalization is only possible to a certain extent and individual adaptations have to be considered.

Apart from that, Rickards and Moger identified creativity within the leadership as a factor of success for project managers. Based in their research they came up with the following seven factors of team development that a project manager should pay close attention to:

- Create a platform of understanding

- Generate a shared vision

- Create a positive climate

- Encourage resilience

- Acknowledge idea owners

- Importing external knowledge

- Learn from experience [13] (p. 280)

Limitations and Criticism

Even though Tuckman's model set the basis for decades of research about the development and formation of groups and teams, it has some limitations and weaknesses. Some of those were identified by Tuckman himself, others later on by other researchers and scientists.

In his publication of the model in 1965, Tuckman already mentiones several limitations and weaknesses. One of those was the observation that not all observed groups in the study experienced all of the stages or sometimes had more than the original 4. He concludes that environmental conditions influence the team development and can lead to adaptations in the model. [1]

Another point of cristicism is the generalization and simplification of the model. This is also brought up by Rickards and Moger in 2000, claiming that Tuckman's model is simplified and therefore can only be used as an idealization of team development. While the authors acknowledge the high amount of face validity of the model, they argue it lacks complexity throughout the phases and therefore does not suitable to describe real-life group development processes. In particular, they came up with two questions that Tuckman did not adress: "What if the storm stage never ends?" and "What is needed to exceed performance norms?". [13] Morita and Burns voiced similar concerns about a discrepancy of expected and observed trust in the process, that might have a negative impact on team performance. [15]

Cassidy identified another issue in the Joumal of Experiential Education in 2006. In her research she discovered that conflict can appear in various phases during the development process. While Tuckman assigned those disputes especially to the storming stage, Cassidy argued that conflict should not be defined in a single phase, but can be observed throughout the entire project life cycle. [16]

Adaptations

Since Tuckman published his research over 50 years ago, there have been various new contributions to the field based on the initial model. Some of them have extended the model, others have changed certain aspects. In the following the most important and relevant adaptions will be covered.

Extended model (Adjourning)

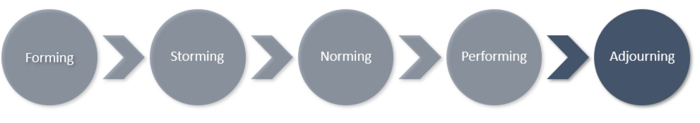

In 1977 Bruce Tuckman reviewed his own model together with Mary Ann Conover Jensen, a doctoral candidate in counselling psychology. They analyzed additional literature regarding the topic of group formation. They published their results under the title "Stages of Small-Group Development Revisited" in Group & Organization Studies in december 1977. [9]

Tuckman and Jensen discovered that most literature supported the model. While at that time only one study had tested the model empirically (Runkel et al 1971), most researchers came to similar results and models or even used Tuckman's original. However, they noticed one discrepancy. In most studies the teams were experiencing an additional phase. Tuckman and Jensen called this new stage Adjourning and characterized it similarly to the initial model (see Figure 3). [9]

The new phase is ocurring after the Performing stage and is about the seperation and the death of the group. Since projects have a fixed start and end, seperation is an issue for all project teams. It is especially important for those who use a Life-Cylce model for team development. Seperation cannot be included in the Performing stage, since the members have to deal personal feelings about the termination of the project and the break-up of the team. Based on those considerations, Tuckman modified and extended his own model with the inclusion of Adjourning as a fifth stage. [9] [2]

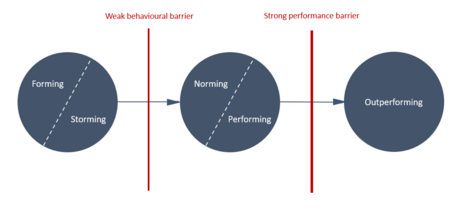

Creative Leadership Processes

In 2002, Susan Moger and Tudor Rickards evaluated existing team development models and their issues and challenges. They came to the conclusion that Tuckman's model is idealized and has some major weaknesses. However, Moger and Rickards used the Tuckman model as a basis to develop their own ideas and improve it. The main idea of the Creative Leadership model are two barriers that the initial model is missing: A weak behavioural after the storming stage and a strong performance barrier after the performance phase (see Figure 4).

The first barrier is about interpersonal conflicts. In Tuckman's model, the team solves these issues that ocurr during the storming phase and moves on to a Norming, where a sense of unity develops. Moger and Rickards ask in their model: "What if the storm stage never ends?" While this is relatively easy to overcome, some groups might not be able to and therefore struggle with interpersonal conflicts throughout the project. All in all, most of the teams can pass this stage on move on to the Norming phase.

The second barrier is harder to overcome and is more about performance than emotions. This hurdle, which leads to a new stage called Outperforming, is stronger than the first one and a large percentage of teams will not be able to clear it. Breaking through this barrier is about exceptional performance inspired by creativity that will lead to extraordinary results. This has several implications for project managers. Moger and Rickards suggest a variety of practices to implement as a project manager to foster creativity and therefore impriove results and pass the second barrier. These suggestions include implementing a Shared Vision, create a postitive climate in the group and encourage resilience amongst others. [13]

Virtual teams

With the emergence of the digitalization and online meetings, Virtual Teams have become more important for companies and organizations. Russell Haines studied the phenomenon of team development in those virtual teams to discover similarities and differences compared to classical development models.

Haines argues that virtual teams follow a similar development process than face-to-face teams. However, there are some differences. Project managers in virtual teams need to take additional measures to establish trust within the team, since this is harder to achieve without direct contact. It is therefore very important to convey a feeling of solidarity. Also, initial struggles in the early phases are important for virtual teams. This is again connected to ensuring trust in the process and the group itself. Overcoming those early conflicts has a major impact on the success of the project. [17]

Before Haines, Johnson et. al made similar remarks in 2002. They also researched on virtual teams' development process and came to the conclusion that Tuckman's model captures it appropriately. One of their additional findings was that in virtual teams leadership is often shared. Instead of one project leader, several members took over part of the responsibility. [18]

Both contributions make clear that Tuckman's model is still relevant today, even though adaptations and evolutions have to be taken into account. However Tuckman was the pioneer for research on group development and still is the basis for the current research and models. [17] [18]

Bibliography

The two most important articles about this model are from the inventor Bruce Tuckman. In his article "Developmental Sequence in small groups" he first published the model and around 12 years later he extended it in "Stages of Small-Group Development Revisited". Those two publications built the basis on further research, however the following literature can be considered more relevant today:

Susan L. Adams & Vittal Anantatmula (2010): "Social and Behavioral Influences on Team Process" in Project Management Journal, 41 (4)

Adams and Anantatmula link the role of the project manager to the different stages of Tuckman's model very clearly. While they mainly use a slightly different model for the team development, they always refer back to Tuckman. Their research highlights the importance of the project manager within the group context and therefore also the role of Tuckman's model within a project management framework. The authors derive practical implications from the model that project managers should follow.

Denise A. Bonebright (2010): "40 years of storming: a historical review of Tuckman's model of small group development" in Human Resource Development International, 13 (1)

Bonebright provides a very good and detailed overview of the history of the model and how it became a scientific standard. She highlights the extension of the model, as well as its limitations. In the later part of the article she gives more information about the additional research on the model and the topic. Overall the article outlines the model with all its features and characteristics, further research and limitations. It is a nearly perfect summary of Tuckman's model.

Tudor Rickards & Susan Moger (2002): "Creative Leadership Processes in Project Team Development: An Alternative to Tuckman's Stage Model" in British Journal of Management, 11 (4)

Rickards and Moger base their research on Tuckman's model and suggest some improvements. Namely, they found two barriers for teams to overcome, which Tuckman did not realize. They also have identified several factors that project managers should pay attention to in order to improve their teams' development and success of the project. The article therefore contains several tipps for project managers to improve their teams' development process and their performance. It is especially valuable for the practical application of the model for project managers.

Johnson, Suriya, Yoon, Berrett & La Fleur (2002): "Team development and group processes of virtual learning teams" in Computers & Education, 39 (4)

Especially in the context of the global pandemic 2020/2021, virtual teams become more and more important in the economic work. Johnson et al describe differences and similarities between virtual and classical teams' development process. The article is highly relevant, especially in the context of the pandemic. Their findings make clear that Tuckman's model is still relevant, but adaptions should be made. Supported by Richard Haines' contribution in 2014 this article combines the current trend of virtual teams with the team development model from 1965.

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 Tuckman, B. W. (1965): Developmental Sequence in small groups. Psychological Bulletin, 65 (6), pp. 384-399, https://doi.org/10.1037/h0022100

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Bonebright, D. A. (2010): 40 years of storming: a historical review of Tuckman's model of small group development. Human Resource Development International, 13 (1), pp. 111-120, https://doi.org/10.1080/13678861003589099

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Miller, D. L. (2003): The Stages of Group Development: A Retrospective Study of Dynamic Team Processes. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences, 20 (2), pp. 121-134, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1936-4490.2003.tb00698.x

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Project Management Institute Inc. (2017): Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide) (6th Edition), pp. 51-68

- ↑ Sheard, A.G., Kakabadse, A.P. (2004). A process perspective on leadership and team development. Journal of Management Development, 23 (1), pp. 7-106, https://doi.org/10.1108/02621710410511027

- ↑ Decuyper, S., Dochy, F., Kyndt, E., Raes, E., Van den Bossche, P. (2015): An Exploratory Study of Group Development and Team Learning. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 16 (1), pp. 5-30, https://doi.org/10.1002/hrdq.21201

- ↑ Neuman, G. A., Wright, J. (1999). Team effectiveness: Beyond skills and cognitive ability. Journal of Applied Psychology, 84(3), 376–389, https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.84.3.376

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 George, J., Jones, G. (2016). Essentials of contemporary management (7th ed.). Columbus, OH: McGraw-Hill Education. pp. 362-393

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 Jensen, M. A. C., Tuckman, B. W. (1977): Stages of Small-Group Development Revisited. Group & Organization Studies, 2 (4), pp. 419-427, https://doi.org/10.1177/105960117700200404

- ↑ Stein, J. (2021). Using the Stages of Team Development. Retrieved from https://hr.mit.edu/learning-topics/teams/articles/stages-development

- ↑ Choudrie, J. (2005). Understanding the role of communication and conflict on reengineering team development. Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 18 (1), pp. 64-78, https://doi.org/10.1108/17410390510571493

- ↑ Tang, K.N. (2019). Leadership and Change Management. Springer Singapore. pp. 37-46

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Moger, S., Rickards, T. (2000): Creative Leadership Processes in Project Team Development: An Alternative to Tuckman’s Stage Model. British Journal of Management, 11, pp. 273–283, https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.00173

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Adams, S. L., Anantatmula, V. (2010): Social and Behavioral Influences on Team Process. Project Management Journal, 41 (4), pp. 89-98, https://doi.org/10.1002/pmj.20192

- ↑ Burns, C.M., Morita, P.P. (2014). Trust tokens in team development. Team Performance Management, 20 (1/2), pp. 39-64, https://doi.org/10.1108/TPM-03-2013-0006

- ↑ Cassidy, K. (2006): Tuckman Revisited: Proposing a New Model of Group Development for Practitioners. Joumal of Experiential Education, 29 (3), pp. 413-417, https://doi.org/10.1177/105382590702900318

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Haines, R. (2014). Group development in virtual teams: An experimental reexamination. Computers in Human Behavior, 39, pp. 213–222, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.07.019

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Johnson, S.D., Suriya, C., Yoon, S.W., Berrett, J.V., La Fleur, J. (2002). Team development and group processes of virtual learning teams. Computers & Education, 39 (4), pp. 379-393, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0360-1315(02)00074-X