Logical Framework Approach in Project Planning

Developed by Jens Dines Obel Jepsen

The Logical Framework Approach (LFA) mainly helps organizations address three basic problems for their project management system, which is that: planning is too vague, management responsibility is unclear, and project evaluation often is an adversary process. [1] The last mentioned is caused by a lack of common agreement, on what the project is to achieve, which, as will be illustrated, the LFA can greatly improve. [2]

The methodology is used extensivly in most international NGOs, bi- and multi-lateral aid agencies, and governments supporting development projects. This tool is therefore very useful to be familiar with for any professional individual or organization dealing with, in one way or another, international humanitarian assistance and relief development projects. [3] The great strength of the LFA lies in projects, such as construction, where the overall objective is more or less static, as the approach enables the managers to establish a clear hierarchy of objectives, where each objective on any level of a project or program has a causal link to the overall goal. If applied to projects with a very dynamic nature, the application's rigidity in regard to objectives, which project members are being evaluated on, can result in the pursuit of non value adding objectives. [4]

In the article the basic idea and motivation for utilizing the LFA is covered, thereafter the application of the tool in specifically in the project planning stage is covered, where the main focus will be on developing the Logical Framework Matrix (LFM) or LogFrame. In order to clarify the methodology, and ensure that it is applied correctly, a walk-through is given on a fictional case project. The article will be rounded off with a discussion of limitations and extensions of the LogFrame, and in addition to that a number of implementation advice will be given.

Contents |

Big Idea

The LogFrame is a tool for summarizing a projects design in terms of its core elements, and it is built on the foundations of Management by Objectives. One of its main strengths is its ability to deliver the full overview of the project design and progression in a very compressed format, which thereby makes it a great tool for communicating with stakeholders, even when a face to face conversation is not a possibility.

To understand how to use the LogFrame, one must understand the context of its use, i.e. the LFA. It is the product of a U.S. Agency for International Development initiative in 1969, which aimed at analyzing and diagnosing their project evaluation system. The study revealed three underlying problems the planning was too vague, management responsibility was unclear, and project evaluation were an adversary process. The LFA is essentially a set of tools and an analytical process, which supports objective-oriented project planning and management. It allows the practitioner to structure the project design and handle decision making rationally on the basis of a clear understanding of objectives, the means by which they are to be achieved, and the factors of uncertainty, which can influence the performance of the project or program.

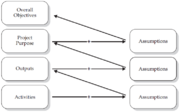

In the LFA the project development process is viewed as hierarchy of events and assumptions related to those events. The overall goal is reached, if the projects purpose is achieved, which is achieved, if the output is produced, which is then again produced, if the activities take place. Furthermore, for each level of events a set of assumptions about the project must hold true for this to result in achievement of the higher level objectives, as it is also illustrated in Figure 1. This goal oriented planning forces the project members to think through the project's logic, and what might influence its performance. It is exactly this structured approach, which is key to the strength of the LFA.

Stages of the LFA

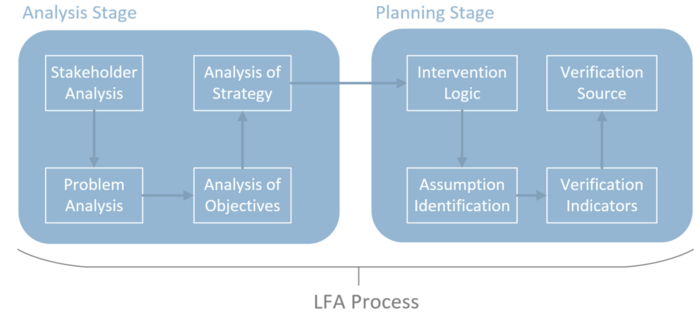

The approach is a two-staged process where the project team would first work on a situational analysis (analysis stage), where the focus is on understanding the context of project and develop a logical explanation of the objective, that are to be pursued. The LFA is outlined in the Figure 2, where the two stages have been illustrated with two rectangles with rounded corners.

One should be aware that the illustration in Figure 2 does not capture the high iterative nature internally in the two stages. Especially the analysis stage is characterized by this, and an example could be the way, that problem analysis might provide new insight about stakeholders and their behavior, while new problems might also surface as more knowledge about stakeholders is discovered. More detailed information about the two phases and their output is shown in the table below.

| Analysis Stage | Planning Stage | |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose | Increase the understanding of the project's stakeholders, key problems, objectives and strategy. This stage should be treated as a iterative learning process. | Translates,the analysis results into an implementation ready operational plan, where the technical project design is devised, i.e. the activities in the project are specified and coordinated in a manner, where they best achieve the desired results. |

| Activities | Stakeholder Analysis, Problem Analysis, Objective Analysis and Strategy Analysis | Developing Logical Framework Matrix, Activity Scheduling and Resource Scheduling |

| Output | From Stakeholder Analysis the most common is a Stakeholder Analysis Matrix and SWOT Matrix.

Problem Tree illustrating the relationship (cause and effect) between identified problems. Objective Tree which is a ‘positive version’ of the problem tree, where the problems are converted into their solutions. The tree describes the causal between project activities, results, purpose and overall objective. Strategy of Intervention can be delivered as a reduced objective tree. The important part is where the amount of intervention alternatives has been reduced to those, which are achievable, not pursued by other projects, feasible and not conflicting with other objectives in program and portfolio. |

LogFrame Matrix which defines the key events of the,project on the four levels below (highest to lowest)

It describes the intervention logic, performance indicators, monitoring, mechanism and assumption on all event levels. |

Application

In the rest of this article the focus is on the application of the LFA in the planning stage, that is the usage of specifically the Log Frame Matrix or LogFrame.

The development of a LogFrame can be initiated by a request from a donor agency or governmental institution for a summary of the project, in the case of a humanitarian development project. Today's complex projects have many stakeholders and partners, and whether it is an engineering, organizational change or societal program or project the need for being able to communicate the key elements consistently and coherently is high. [5] The LogFrame has the ability to efficiently outline the project and findings from the analysis stage of the LFA, and is thereby able to fulfill this need. In the sections below the way of developing a LogFrame, with the characteristics described above, is presented.

Log Frame Matrix Format and Principles

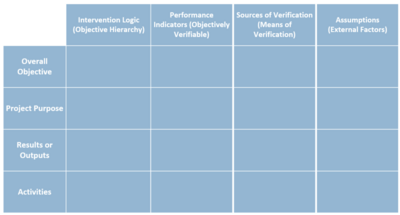

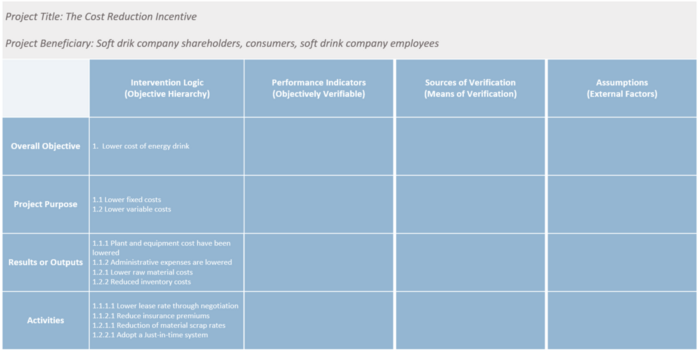

Essentially the matrix is a summary of the work undertaken during the analysis stage, and describes the project in short from the overall objective to the individual activities and external factors. The matrix consists of four columns and four, or more, rows not counting headers. The columns one, two, three and four describes for each event the intervention logic (event relationships), performance indicators (for verification), monitoring mechanisms (sources of verification), and assumptions about external environment. The format of the LogFrame is shown in Figure 3. In the subsections below each column in the LogFrame will be described more in detail, and the header for each indicates the column number.

Process of Completion

Although the title may indicate something else the work with the LogFrame should be treated as an iterative one, but in this section we will discuss it as a linear process.

Column One: The Intervention Logic

This part of the LogFrame contains what the intention of the project is, and how the events herein are causally related. To state this in the matrix one should follow the five steps presented below.

- Define the objective

- Define project purpose

- Define results

- State activities to be undertaken

- Verify the Intervention Logic

Step five is a simple "walkthrough" of the logic tree, which column one constitutes. This step involves starting from the overall objective ensuring, that the lower level objectives supports the achievement of this. This check is performed on each level of the hierarchy, and will thereby end at the activities. This can be referred to as the top down approach.

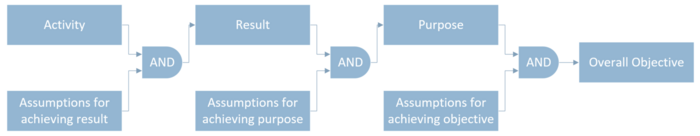

Column Four: Assumptions About External Factors

The assumptions are external factors, over which the management have no control. Furthermore, these factor’s states are critical for the success of the project. The assumptions will along with the objective hierarchy represents the vertical logic in the LogFrame, and the relationship between these two can be illustrated with the logic diagram in Figure 4.

Identifying Assumptions

For each level in the objective hierarchy determine whether this objective is sufficient for this level to result in the level above it to be achieved, if it does not, an assumption will have to be added to the matrix for the causal relationship to be true. For the assumption to be the most useful they must be described in such detail and concreteness, that one would be able to monitor them during the course of the project.

Some example of assumptions could be the ones below.

- Fuel price fluctuations can be absorbed with current budgeting.

- Partnering organization stays supportive of project.

- Local authorities provide protection for deployed volunteers.

It might seem like one should come up with all assumption at once, which could decrease the exhaustiveness these, but most assumptions should already have surfaced during the analysis stage during discussion at the stakeholder analysis, problem analysis and so forth.

Significance and Probability Check

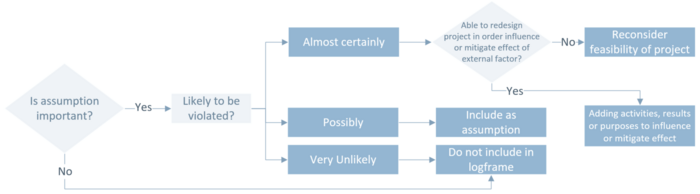

Of course not all assumptions are equally important for the project’s success, some might be minor influencers, while other can, if violated, be so called killing factors. Therefore, the next step is to analyze and determine the significance and probability of a violated assumption, in order to determine the course of action. [6] For each assumption one should decide on the course of action by following the decision process outlined in Figure 5.

All assumptions, which are still contained in the LogFrame at this point, will be monitored during the project and are valuable for development of more extensive risk management plans. At this point each level in the LogFrame should contain both the events in the objective hierarchy including the causal relationships between these, and the assumptions necessary for the higher levels.

Column Two: Objectively Verifiable Indicators

In order to manage the events in the objective hierarchy, one have to be able to monitor and determine the progress and completion of these. This is done through what is known as Objectively Verifiable Indicators (OVI), and these describes the objectives in such detail, that they are measurable and specify the required performance level to be met in order to achieve the overall objective, purpose or result. This importance of performance visibility and awareness is widely articulated as a precondition for project success, as I. Mackenzie and A. Davis also identified as a headline driver of the 2012 Olympics success. “It was, thus, essential that there was... a high level of visibility of performance throughout construction (to expose problems and issues at the earliest point). [7] To determine the OVIs a top-down approach is taken, where that for the overall objective is determined first, which at the planning phase should be clear to the project members. Thereafter, the OVIs can be determined by breaking it down all the way to the individual activities. Many different indicators can be used such as quantities, timing, target groups, locations etc. It is suggested that in order to develop a good indicator one must follow a four step process. [8]

- Identify Indicator

- Set Quantity

- Set Quality

- Specify Time

To see an example of the use of the above see the section titled Example of Application. OVIs should always be as insensitive to subjective opinion of individuals, and ideally different people should arrive at the same OVIs value, if data is collected simultaneously.

Column Three: Sources of Verification

Sources of verification or means of verification are used interchangeably about the source from where the necessary data to generate the indicator values originates. Each SOV should specify that below.

- What data is to be made available? (medical records, interviews, surveys etc.)

- Who collects and provides the data?

- What form is the data in? (statistical database, financial statements etc.)

- How regularly is the data provided? (continuously, monthly etc.)

In case an indicator does not have a suitable SOV, i.e. it is infeasible to collect data from this source, it should either be modified or replaced by a verifiable indicator.

Example of Application

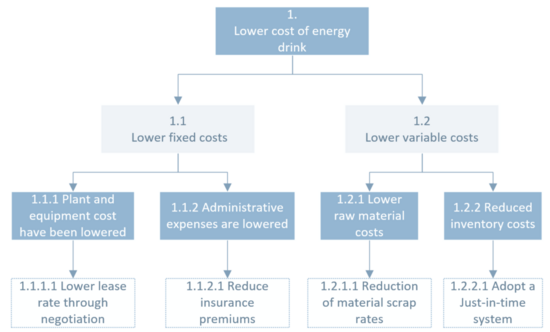

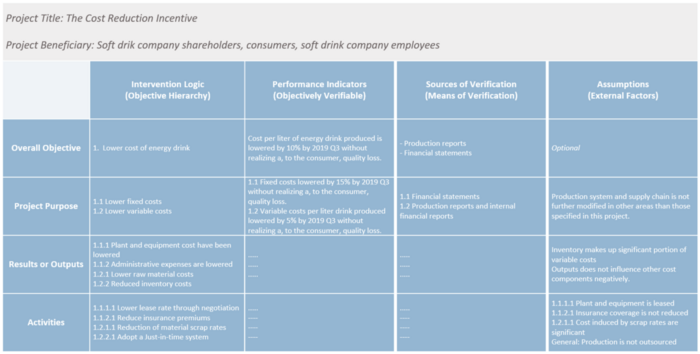

A soft drinks company want to lower the costs of producing their popular energy drink. The project team have completed the analysis stage of the LFA and have determined the strategy of intervention, which is presented as the reduced objective tree seen in Figure 6.

Intervention Logic

This intervention strategy is to be included in the LogFrame’s first column, where the overall objective is positioned in the top of the objective tree. By inserting the objectives in the LogFrame the result shown in Figure 7 is obtained. In this case the number of activities are limited, but in a real project the activities will be many and their interdependencies complex, which is why, it is common practice to include the activities in a separate page or for more complex projects network diagrams or Gantt Chart. [9] The activities are here presented in same page as the remaining objectives.

Assumptions about External Factors

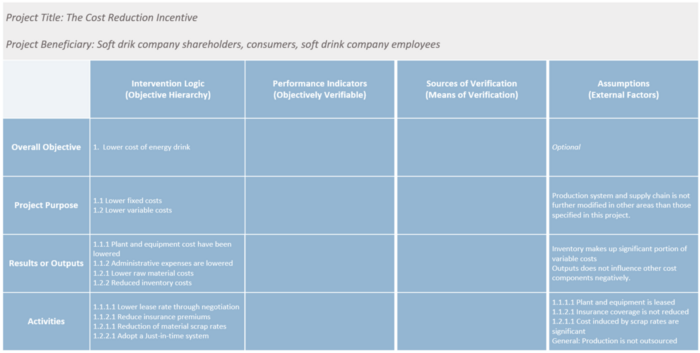

At this point the assumptions for each level, besides the overall objective, are identified. These can either be related to one specific assumption, several or all on that level as also seen in Figure 8.

The LogFrame shows that in order to achieve the result “1.1.2 Administrative expenses are lowered” the activity “1.1.2.1 Reduce insurance premiums” need to be obtained without reducing the insurance coverage, as this otherwise would simply increase the cost of an accident.

Objectively Verifiable Indicators and Sources of Verification

At this stage the vertical logic has been made clear, and the horizontal logic should be assessed, that is the performance indicators and the data sources are to be determined.

Using the four step process described in the section titled Objectively Verifiable Indicators and Sources of Verification, one could establish the following indicator or OVI for Purpose 1.2.

- Step 1 Identify Indicator

- Lowered variable cost per liter energy drink

- Step 2 Set Quantity

- Lowered variable cost per liter energy drink by 5%

- Step 3 Set Quality

- Lowered variable cost per liter energy drink by 5%, without realizing a, to the consumer, quality loss.

- Step 4 Specify Time

- Variable costs per liter drink produced lowered by 5% by 2019 Q3 without realizing a, to the consumer, quality loss.

Now the source of verification is to be determined. In this case the amount of produced energy drink would have to be collected from production reports or similar, while variable costs are found in internal financial reports. OVIs and SOVs for the overall objective and purpose level have been determined, while the remaining ones have been left out for simplicity’s sake. The final LogFrame is found in Figure 9.

With the filled in LogFrame the project management can effectively communicate the project design to stakeholders and modify “on the go” if needed. [10] As the LogFrame presents in short the desired state of the project at completion, it is very useful for project monitoring and evaluation, since all indicators are linked to an activity scheduled and the underlying assumptions.

Limitations and Suggestions

The limitations referred to in the application section are described here, and although some of them can stand alone without references to literature, the majority will be those mentioned in previous literature.

- If over-emphasizing the objectives and external factors set up during the initial phases, the project administration can become immensely rigid, as it will not allow for the changing variables of the environment to have an impact on the scope and objectives of the project. A response to this would be to arrange regular review meetings, where the project's elements are adjusted if needed. [11]

- The approach for the significance and probability check, which is shown in Assumptions About External Factors, does indeed assess and mitigate the risks implied by the assumptions, but the way of treating significance as a binary variable is highly unrealistic, and could even have an impact on the risk inherent in the project. By assuming binary behavior, the probability of including an assumption, which does have a significant impact on the project if violated, is higher, than if the significance were scored on for example a scale from one to five.

- Many practitioner have found the LFA helpful for structuring their thinking, but the have also expressed that it is difficult to communicate the way of thinking. This problem is amplified, when communication is cross-cultural or subject to translation. [12]

Regarding limitation two above, it is suggested, by the author of the article, that the decision to redesign the project, just include the assumption or discard the assumption should be made based on a risk score computed from a significance score and probability score.

Annotated Bibliography

European Integration Office, Guide to The Logical Framework Approach: A Key Tool for Project Cycle Management, 2011, p. 12, Belgrade

A guide developed for practitioners in the field of design, implementation and management of development projects. The publication is a relatively new one from 2011, and can therefore be treated at the current state of practice in the industry. The reader is introduced to the LFA through four main steps, which are a high level overview of the framework and context, a description of the analysis stage, the description of preparing and using the LFM, and lastly a thorough presentation of the linkage between the LFA and various phases of Project Cycle Management. Especially the last mentioned part provides a more detailed look, at how the LFA is used as a tool for improving the management of project in their entire cycle.

Bakewell, Oliver, Garbutt, Anne, The Use and Abuse of the Logical Framework Approach, November 2005

Bakewill and Garbutt provides an extensive review of the current practice of using the LFA. The publication serves as much the purpose of pinpointing the disadvantages as it does pinpointing the advantages, which makes it stand out compared a lot of other literature, which seems to often take a standpoint in which the methodology is either praised or criticized. This is the author of this wiki article's own impression of the literature commonly available.

Practical Concepts Incorporated (PCI), Guidelines for Teaching Logical Framework Concepts, 1975, Washington, DC

During the past 40 years of the Logical Framework Approach's existence many modifications and adaptions of it have been made, for example those suggested by Agency for International Development. [13] This publication by PCI documents the earliest development of the LFA, and the analysis and assessment of the U.S. Agency of International Development's project management system, which identified the need for the framework. One can benefit from this article, as it provides a description of the LFA in its purest form, so to speak. It is therefore highly recommended for any practitioner or researcher, who is involved with the LFA, to review this publication.

References

- ↑ Practical Concepts Incorporated (PCI), Guidelines for Teaching Logical Framework Concepts, 1975, p. 4, Washington, DC

- ↑ JICA, EEAA,GUIDANCE FOR COUNTERMEASURE PLANNING WITH LOGICAL FRAMEWORK APPROACH Guidance for Countermeasure Planning with Logical Framework Approach, July 2008, pp. 9-11

- ↑ Ramboll Management and DACU, GUIDE TO THE LOGICAL FRAMEWORK APPROACH: A KEY TOOL TO PROJECT CYCLE MANAGEMENT, 2007, p. 4

- ↑ Trans-European Cooperation Scheme for Higher Education (Tempus), Objective oriented project design and management, Publication date unknown, p. 6, Brussels

- ↑ Bakewell, Oliver, Garbutt, Anne, The Use and Abuse of the Logical Framework Approach, November 2005, Available from: http://www.intrac.org/data/files/resources/518/The-Use-and-Abuse-of-the-Logical-Framework-Approach.pdf

- ↑ European Integration Office, Guide to The Logical Framework Approach: A Key Tool for Project Cycle Management, 2011, p. 41, Belgrade

- ↑ Mackenzie, Ian, Davies, Andrew, 'Lessons Learned from the London 2012 Games Construction Project’, London Delivery Authority, October 2011, p. 4, Available from: http://learninglegacy.independent.gov.uk/

- ↑ H. Sartorious, Rolf, 1991, The Logical Framework Approach to Project Design and Management, p. 143, Chantilly, Virginia

- ↑ Department for International Development 2009, Guidance on using the revised Logical Framework, February 2009, United Kingdom.

- ↑ H. Sartorious, Rolf, 1991, The Logical Framework Approach to Project Design and Management, p. 140, Chantilly, Virginia

- ↑ European Integration Office, Guide to The Logical Framework Approach: A Key Tool for Project Cycle Management, 2011, p. 12, Belgrade

- ↑ Bakewell, Oliver, Garbutt, Anne, The Use and Abuse of the Logical Framework Approach, November 2005, pp. 17-18

- ↑ Agency for International Development, THE LOGICAL FRAMEWORK MODIFICATIONS BASED ON EXPERIENCE, 1975, Washington, DC, Program Methods and Evaluation Division.