Virtual project management

Developed by Kasper Kjær Rasmussen

New dimension into project management appeared with the rise of the Internet and development of collaborative software. Virtual teams, where people work with colleagues in remote locations are now a reality in the workplace environment. If this trend continues, virtual working will increasingly influence the way humanity operate, and the ‘effective virtual team worker’ will be a valued asset. A key benefit of forming virtual teams is the ability to cost-effectively tap into a wide pool of talent from various locations.[1]

Most project managers with a few years experience or more are likely to have managed a project, where some or even all of the members were remotely located. How different is managing a virtual project team from a co-located team? Are there additional considerations or risks involved in managing a virtual team?

Contents |

Definitions

Virtual program management (VPM) is management of a project done by a virtual team, though it rarely may refer to a project implementing a virtual environment, it is noted that managing a virtual project is fundamentally different from managing traditional projects, combining concerns of telecommuting and global collaboration (culture, time zones, language).[2][3]

A Virtual Team also known as a Geographically Dispersed Team (GDT) – is a group of individuals, who work across time, space and organizational boundaries with links strengthened by webs of communication technology. They have complementary skills and are committed to a common purpose; have interdependent performance goals, and share an approach to work for which they hold themselves mutually accountable. Geographically dispersed teams allow organizations to hire and retain the best people regardless of location.[4]

Virtual team is an alternative of business organization, which is characterized by the presence of a physical office. However, in practice, more common is the mixed model, when the company has a physical office used to solve most of the problems of remote workers, outsourcing or freelancing.

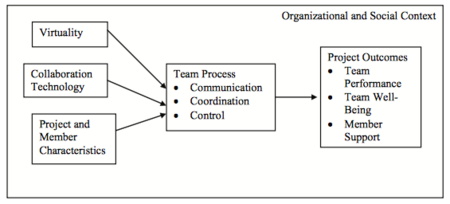

Conceptual Model

Input Factors:

- Virtuality is a term that is defined in a variety of ways, but typically with respect to dispersion. Virtual teams can be dispersed on many dimensions, most often geographically and also in time, organizational affiliation, culture and technology.[5]

- Collaboration technology an integrated and flexible set of tools for structuring process, supporting task requirements, and communicating among project members. These characteristics are not fixed, but instead can be adapted by team members as they develop knowledge of the task, each other, and the technology itself.[5]

- Project and member characteristics can be examined across these common factors: project complexity can be affected by the extent to which teams have variety in their size, culture, language, member characteristics, resources, and knowledge; project scope can be affected by the extent of duration, innovation, and breadth; project risk is defined typically in terms of different categories of risk in different phases of the project.[5]

Team Process Factors:

- Communication is the process, which people convey meaning to one another through the exchange of messages and information to carry out project activities.[5]

- Coordination can be defined as the mechanisms through which people, technology and other resources are combined to carry out the activities required to attain project goals.[5]

- Control is the process of monitoring and measuring project activities to anticipate and manage variances from plans and goals.[5]

Team Outcome Factors: Time-interaction-performance (TIP) theory [6] provides a systemic and multi-dimensional picture of team output. TIP theory posits three simultaneous aspects of team functioning: team performance, which means getting the task done; team well-being, or the relations among team members and member support, which is the relationship of the individual to the team.[5]

Virtual Teams

Types of Virtual Teams[7][8]

- Networked Teams are generally geographically dispersed and may include members from outside the organization. Many times these are composed of cross-functional members who are brought together to share their expertise and knowledge on a specific issue or topic. Membership is fluid that is to say, new members are added when necessary and existing members are removed whenever their role is completed. The lifespan of a networked virtual team depends on how much time it takes to resolve the issue. The networked teams dissolve after completion of assigned task. Networked teams are widely used in consulting firms and technology companies.

For example, Richard Maclean & Associates, an environmental, health and safety (EHS) management consulting firm located in Arizona serving both domestic and international clients relies on other academic and government research organizations like Center for Environmental Innovation, Air and Waste Management Association, Meridian Institute, to name a few to stay competitive at a low cost.

- Parallel Teams are generally formed by members of the same organization. While delivering their primary assigned role in the organization, they take parallel responsibility, hence the term parallel team. Generally this team is formed to review a process or a problem at hand and make recommendations. Unlike networked teams, these have constant membership, which remains intact till the desired objective is achieved. Teams are generally formed for short span of time, they are very effective in multinational organizations, where a global perspective is needed.

For example, many consumer goods companies team up their sales, marketing, manufacturing and R&D professionals working at different locations into parallel virtual teams to make recommendations for the local adaptation of their product specifications.

- Project or Product Development Teams are the classic virtual teams, which were developed as early as 1990s. These were actually the pioneer in the development of virtual teams. The project or product development virtual teams are composed of subject, experts brought together from different parts of the globe to perform a clearly outlined task involving development of a new product, information system or organizational process, with specific and measurable deliverables. Like network teams their membership is also fluid, but unlike parallel teams, these can make decisions, not just recommendations. These are typically found in R&D division of the product-based companies.

For example, Whirlpool brought together a team of experts from United States, Brazil and Italy for a period of 2 years to develop a chlorofluorocarbon-free refrigerator.

- Work, Production or Functional Teams are formed when members of one role come together to perform single type of ongoing day-to-day work. Here members have clearly defined role and work independently. All of the members’ work combine together to give the final solution.

For example, in order to reduce cost many organizations are outsourcing their backend HR operations or even for that matter the recruitment agencies form functional virtual teams for their clients.

- Service Teams have members across different time zones, therefore when one member in Asia goes to sleep, the other member in America wakes up to answer your queries. This is the basic model of service teams, which are formed of members spread across widely distinct geographic locations and though each member works independently, but they together maintain 24-hours working day. It is like relay race where one takes baton from the other and run the race. These are effective as technical and customer support teams.

For example, cellular companies, banks, software companies have call/support centre, which answer calls and help you to solve problems.

- Action Teams are actually ad-hoc teams formed for a very short duration of time. Members of action team are brought together to provide immediate response to a problem and they disperse as soon as the problem is solved.

For example, NASA forms a virtual action team consisting of leaders sitting in NASA headquarters in Houston, astronauts in space shuttle, engineers & scientists in different locations across the globe for a successful space mission.

- Management Teams are formed by managers of an organization, who works from different cities or countries. These members largely get together to discuss corporate level strategies and activities. These are applicable to almost every organization, which has office in more than one location.

- Offshore ISD outsourcing teams, they are independent service provider teams, which a company can subcontract portions of work to. These teams usually work in conjunction with an onshore team. Offshore ISD is commonly used for software development as well as international R&D projects.

Pros & Cons

Advantages:

- Increased productivity: work is not limited to the traditional 9-5 workday as a ‘follow the sun approach’, it can result in shorter time to market of products, technology and services.[9]

- Extended market opportunity: an ability to establish a ‘presence’ with customers worldwide. This can also enable small businesses to compete on a global scale without limiting the customer base.[9]

- Knowledge transfer: this enables companies to compete on a global scale by bringing together people with different types of knowledge into ‘online’ meetings from around the globe.[9]

Disadvantages:

- Communication deficiency: failure to communicate properly due to the elimination of body language or the increase of incorrect assumptions based upon cultural difference or lack of understanding.[9]

- Poor leadership and management: inability to communicate and deliver clear messages to the team.[9]

- Incompetent team members: lazy or individuals with lack of expertise or knowledge can have a negative impact on the team.[9]

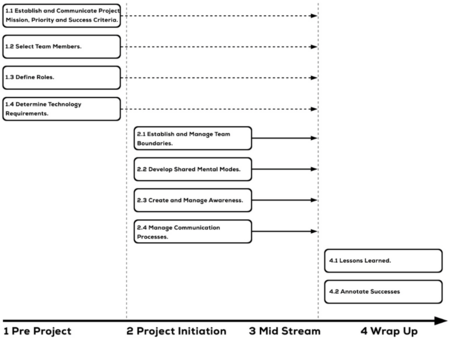

Virtual project success factors

A good example of “stages” approach is shown in "Guidelines for managing virtual teams over the life of a project" with a solid set of guidelines introduced by Beranek in book [11].

This approach is useful during the implementation planning process, as it could allow team members and the leader to map a route to follow, in order to attempt for success maximization.

Another way was suggested by Maznevski & Chudoba in their book [12] developed a grounded theory of global virtual team dynamics and effectiveness. The theory offers a series of seven propositions that describe what that effective virtual teams are, based on interaction (a set of communication incidents that are dependent on the team's structure and process), a rhythm (temporal regular intensive face-to-face meetings), and the structural characteristics of each project context (like tasks, groups, and technologies).

- Proposition 1: The higher the level of decision process served by an incident, the richer the medium appropriated, and the longer the incident's duration.

- Proposition 2: The more complex the message content of an incident, the richer the medium appropriated, and the longer the incident's duration.

- Proposition 3: If a rich medium is not required, the most accessible medium will be used.

- Proposition 4: If an incident serves multiple functions of messages, its medium and duration will be shaped by the highest function and the most complexity.

- Proposition 5A: The higher the task's required level of interdependence, the more communication incidents will be initiated.

- Proposition 5B: The more complex the task, the more complex the incidents messages will be.

- Proposition 6A: The greater the organizational and geographic boundaries spanned by a global virtual team's members, and the greater the cultural and professional differences among team members, the more complex the team's messages will be.

- Proposition 6B: The stronger the shared view and relationships among global virtual team members, the less complex the team's messages will be.

- Proposition 6C: Other things being equal, in effective global virtual teams the receiving member's preferences and context determine an incident's medium.

- Proposition 7: Effective global virtual teams develop a rhythmic temporal pattern of interaction incidents, with the rhythm being defined by regular intensive face- to-face meetings devoted to higher level decision processes, complex messages, and relationship building.

Challenges of managing virtual projects

- Communication[14]

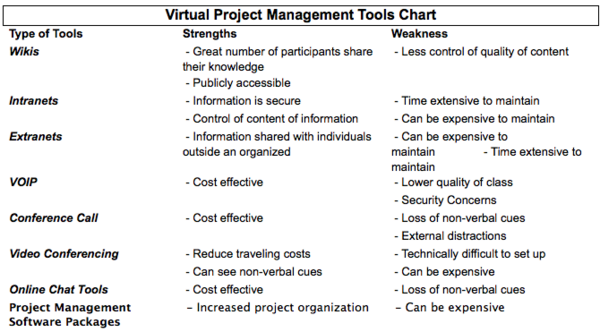

Communication builds trust. It provides guidance, and the phrase “collaborative teams” infers that communication is taking place. Lack of communication is the one hurdle that really distinguishes the challenges faced by virtual teams. Blaine and Bowen build on Daft and Wiginton proposition that it is not quantity of information that reduces equivocally, but the quality or “richness” of that information. Richness is a property of the medium used to convey information, which includes the mediums’ ability to provide immediate feedback, use multiple cues and channels, and allow personalization and language variety. Communication can be decomposed into its data capacity and richness. A phone, for instance would be high in richness, but low in data capacity, while reports would be high in data capacity, but low in richness. Recent technologies have simply provided additional mechanisms of communication. With each new tool in the toolbox, there is a chance that exist more appropriate communication tools than existed a decade ago.

The effects of various types of communication mechanisms were the subject of Egger’s study. He approach the topic through the framework of a dilemma game, also called the prisoners’ dilemma, public good games, or free riding game. It means that with collaboration two individuals achieve a better payoff, but must rely on the other person to get that better payoff. There is also an incentive to cheat, or free ride where there is gain by one member at the other’s expense. They conducted seven free riding experiments where the difference was the type of communication related to business interfaces. These included communication by reference, identification, lecture, talk-show, audio-conference, video-conference, and table conference. Eggert evaluated the cooperation level and the stability of the cooperation for each method. He found that reference and identification produced low levels of cooperation were highly stable. Lecture, talk show and audio-conference produced intermediate levels of cooperation that were unstable. Finally, video and table conferencing produced a high level of cooperation and were highly stable as well. He concluded that the business implication with both auditory and visual communication play key roles for efficient outcomes.

Certainly video and face-to-face conferencing is not always possible with all virtual team communications. Therefore, several authors have provided guidelines for alleviating communication problems. Gould suggests the following practices:

- Including face-to face when possible, give team members a sense of how the overall project is going by providing schedules

- Establish a code of conduct to avoid delays (i.e. acknowledging email)

- Don’t let team members vanish (i.e. use calendars)

- Augment text-only communications with charts, pictures and diagrams

- Develop trust

Peterson and Stohr also have four tips for effective distance communication:

- Standards for availability and acknowledgement

- Team members replace lost context in their communication

- Members regularly use synchronous communication

- Senders take responsibility for prioritizing their communication

Other practical suggestions include establishing a communication centre with a project web site. This ensures that everyone is working from the same documents and has the up-to-date information on the team’s progress (Barker). Feldman concurs with this idea and adds that putting a project on the Internet can help build an audit trail to record the documents and details.

- Developing trust

Face-to-face contact, mentioned above, is a key to developing trust and this is initiated by a formal team building sessions with a facilitator to “agree to the relationship” and define the rules as to how the team is going to office. Informal contact is also important, e.g. sitting down over lunch to break barriers. Another benefit of spending at least two days together included going through the “forming, storming, norming, performing” dynamic more quickly. It is generally assumed that members only really know each other if they could put a face to a name.

Knowing each other was reported to lead to higher efficiency. Problems are easier to solve if team knows that person on the other side of the line. It was reported that trust was built over time, based on long-term consistent performance and behaviour that created confidence. It was estimated that range between three and nine months is the time needed to develop a comfort level and trust level with new members. Once trust is there, people will report problems to the project leader before they became official, so the leader could still do something about them. It was also advantageous to trust building if the project leader and project manager had worked together at the same site for a long time, even if they were later on different continents.[15]

It takes time for newcomers to the company to gain the trust of their colleagues. They are able to trust people’s expertise primarily with their developing knowledge of the company as well as knowledge of the task. One Project Manager commented that newcomers to the company would attend meetings, take notes, ask questions and say “I’ll get back to you”, with the result that the team was at least one week behind on certain issues. A main reason that developing trust and a comfort level is “a major challenge” is the high turnover of project leaders, project managers and members.[15]

- Cultural Differences

Virtual Project Managers must be cognizant of cultural differences for the purpose of ensuring that the communication remains effective at all times. From 15 to 20 percent of culture is readily visible and these characteristics include, but are not limited to language, ethnicity, dress, laws, art, architecture, and other attributes that are immediately obvious meeting a person from a particular culture. From 75 to 80 percent of culture is hidden below the surface of most people’s awareness. These characteristics are deeply ingrained attitudes, beliefs, prejudices, and expectations that comprise an individual’s worldview (Brown, Huettner, James-Tanny, 2007). A project manager should respect the cultures of different team members, while at the same time create a common work culture that all team members can share.

A project manager should to make sure that communication, between team members from different countries, is explicit and well written out. Shorthand acronyms or abbreviations may not be known by all team members which can cause confusion and should be avoided at all costs. For example, an individual in an email may ask for a deliverable by “EOD”. Team members from different cultures may not know that “EOD” is an acronym for “end of day”, and furthermore the “EOD” means different things to different people. If you have two members, one in New York and one in Los Angeles, end of the day for the New York team member is 6:00pm EST (Eastern Standard Time), which is 3:00pm PST (Pacific Standard Time). To avoid this type of confusion, it is recommended that all communications be thorough, clear and explicit.[13]

- The leadership challenge

While all project managers are concerned with managing the People, Processes, Information and Technology (PPTI) related to a project, PMs managing a virtual project team have additional hurdles to overcome. While a project manager may traditionally focus on one project with one team in one location, the modern, virtual PM must manage a dispersed team of contributors[16]. Thus the need for effective project management techniques is paramount. Yet it is not the “hard” or technical skills that a PM must develop to successfully make the transition to managing virtual projects, rather it is his “soft skills” and interpersonal competencies that must be adapted. The added complexity of relationship dynamics in a virtual team environment render traditional approaches to project management inadequate.[17]

In a virtual project setting, it is critical that the PM assumes the role of the central project leader, assuming additional responsibility than in a typical project by managing project processes, inter-team communications, and coordinating tasks. As the project leader, the PM must become more active in assuming two key roles: performance management and team development.[17][18]

To manage team performance, the PM must: clearly specify the goals and direction of all tasks for all team members[16]; establish routine and habitual meetings and communications; establish standard operating procedures (SOPs) and project processes; and continually support the team to overcome challenges in order to maintain momentum. To develop “coherence” amongst virtual team members, the PM must create opportunities for trust-building and provide recognition for successes to foster motivation.[19]

- Managing the task

Setting clear goals and objectives are important in any project. When a portion of the team is virtual, this is all the more important. The virtual team workers cannot physically walk into your office to ask clarifying questions, review goal statements posted on the walls or physically attend team focus meetings. Setting clear goals, expectations, and how each virtual member’s contributions align to the goals is crucial. In order to allow inclusion of virtual team members, consider adding the project team goal statements on the front page of team work sites or find other ways of making them readily available.[1]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 CIO. "How to manage a virtual project team". http://www.cio.com.au/article/368495/how_manage_virtual_project_team/

- ↑ Velagapudi, Mridula. "Why You Cannot Avoid Virtual Project Management 2012 Onwards" April 13, 2012 http://blog.bootstraptoday.com/2012/04/13/why-you-cannot-avoid-virtual-project-management-2012-onwards/

- ↑ Global Knowledge."Virtual Project Management (course)". http://www.globalknowledge.com/training/course.asp?pageid=9&courseid=10276&catid=196&country=United+States

- ↑ "Definition of Virtual Teams", http://managementhelp.org/groups/virtual/defined.pdf

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 "The Practice and Promise of Virtual Project Management", http://www.isqa.unomaha.edu/dkhazanchi/vita/Research%20Papers/91.pdf

- ↑ "Time, Interaction, and Performance (TIP)" Joseph E. Mcgrath. University of Illinois. http://sgr.sagepub.com/content/22/2/147.abstract

- ↑ Management Study Guide. "Different Types of Virtual Teams". http://managementstudyguide.com/types-of-virtual-teams.htm

- ↑ Management Help. "Virtual Teams". http://managementhelp.org/groups/virtual/defined.pdf

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 ExpathKnowHow. "Virtual Teams". http://www.expatknowhow.com/Documents/virtual-teams.pdf

- ↑ "Motivation in Virtual Project Management" Raul Ferrer Conill. http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:624038/FULLTEXT01.pdf

- ↑ Beranek, P.M., Broder, J., Reinig, B.A., Romano Jr., N.C. & Sump, S. (2005). Management of virtual project teams: Guidelines for team leaders. Communications of the Association for information systems, vol.16:1, pp. 247-259.

- ↑ Maznevski, M.L. & Chudoba, K.M. (2000). Bridging space over time: Global virtual team dynamics and effectiveness. Organization science, vol.11:5, pp.473-492.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Virtual Project Management Tools and Techniques. "Overview of Virtual Project Management (VPM)". http://pm440.pbworks.com/w/page/25397227/Virtual%20Project%20Management%20Tools%20and%20Techniques

- ↑ "Virtual Project Management", A term paper for MSIS 489. Mike Rolfes. http://www.umsl.edu/~sauterv/analysis/488_f01_papers/rolfes.htm

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Margaret Oertig Thomas Buergi, (2006),"The challenges of managing cross#cultural virtual project teams", Team Performance Management: An International Journal, Vol. 12 Iss 1/2 pp. 23 - 30 http://www.emeraldinsight.com/doi/pdfplus/10.1108/13527590610652774

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Hofer, Bernhard Rudolf. "Technology Acceptance As a Trigger for Successful Virtual Project Management." Thesis. University of Nebraska at Omaha, 2009. 14 Aug. 2009. Web.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Lee-Kelley, Liz, Alf Crossman, and Anne Cannings. "A Social Interaction Approach to Managing the "invisibles" of Virtual Teams." Industrial Management & Data Systems 104.8 (2004): 650-57. Emerald. Web.

- ↑ ACADEMIC TEXTS BY ALEXANDRA KAPELOS-PETERS. "Managing Virtual Teams" http://www.alexandrakp.com/text/2010/11/virtual-pm/

- ↑ Hunsaker, Phillip L., and Johanna S. Hunsaker. "Virtual Teams: a Leader's Guide." Team Performance Management 14.1/2 (2008): 86-101. Emerald. Web.

Literature

[1] "Virtual Project Management: Software Solutions for Today and the Future", Paul E. McMaho.

[2] "PROMONT – A Project Management Ontology as a Reference for Virtual Project Organizations", Sven Abels, Frederik Ahlemann, Axel Hahn, Kevin Hausmann, Jan Strickmann.

[3] "Global Software Development: Managing Virtual Teams and Environments", Dale Walter Karolak, 1999.

[4] "Project Management: A Systems Approach to Planning, Scheduling, and Controlling", Harold R. Kerzner.