Life Cycle Assessment

This article focuses on Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), which is a method used to evaluate the environmental impact of a product, process or activity over its entire life cycle. The goal of LCA is to identify and quantify the potential environmental impacts of a product or service, from the extraction of raw materials, through the manufacturing and use phases, to final disposal. The LCA process provides a comprehensive and scientifically robust analysis of the environmental impact of a product, taking into account its entire life cycle.

In the context of project, program, and portfolio management, LCA can be used to evaluate the sustainability of projects and to identify opportunities for improvement. For example, a project manager may use LCA to assess the environmental impact of different project options and to prioritize projects that have the lowest environmental impact. Additionally, a portfolio manager may use LCA to assess the environmental impact of different investment options and to prioritize investments in companies that are actively engaging in sustainability.

LCA can also provide valuable information for stakeholders, including investors, customers, and policymakers, who are interested in understanding the environmental impact of the products and services they use and invest in, and help them make more informed decisions.

In conclusion, LCA can be a valuable tool for project, program, and portfolio management, as it provides a comprehensive and scientifically robust analysis of the environmental impact of projects and enables managers to identify opportunities for improvement and make informed decisions. As sustainability becomes increasingly important to investors and customers, LCA will play an increasingly important role in project, program, and portfolio management, helping companies and investors to achieve their sustainability goals and drive positive change in the world.

Contents |

History of LCA

Origins

The idea of LCA was conceived in the 1960s, when environmental degradation and limitations of raw materials and energy resources sparked interest in finding ways to cumulatively account for energy use and to project future resource supplies and use. This practice sees its roots in studies carried out uncoordinately in the US and Northern Europe regarding packagings, with a focus on energy use and a few emissions. At first, studies were primarly done for companies for internal use, usually without informing styakeholders, since interest in sustainability was very limited to few at that time. One example is an internal study initiated in 1969 for The Coca-Cola Company that laid the foundation for the current methods of life cycle inventory analysis in the United States. This study quantified the raw materials, fuels, and environmental loadings from the manufacturing processes for various beverage containers, in order to compare their impact on the environment and their depletion of natural resources. The aim was to identify the container with the lowest release to the environment and the least impact on natural resource supply. After a stall in the 1970s, it was just during the 1980s and 1990s, when international collaboration and coordination in the scientific community started to take place and universities engaged in working on method development, that the application of LCA spreaded across industry and governments, resulting in an increasing range of products and systems included into LCA studies. The term Life Cycle Assessment was itself coined in 1990 and, since then, this practice has seen a constant increase in both range of methodologies and applications.[1] [2]

Development and Standardisation

Starting from the early 1990s, the global Society for Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry (SETAC) organised multiple workshops with the aim of developing a common "Technical Framework for LCA". The series culminated in the development of a Code of Practice for LCA, the first official guidelines for LCA in 1993. Towards the end of the decade, leading researchers of the SETAC working group on life cycle impact assessment initiated a collaboration with the United Nations Environmental Program (UNEP) to expand the global dissemination of good LCA practices beyond the primary activity centers of Europe, North America, and Japan. The partnership was aimed at ensuring the continued development of such practices on a global scale, and it culminated in 2002 in the launch of the UNEP/SETAC Life Cycle Initiative. This initiative brought a wide scientific consensus on LCA. Consequently to the publication of the first Code of Practice, a formal standardization process was initiated by the International Organization of Standardization (ISO) to develop a global standard for LCA. Over a period of seven years, the development of standards led to the adoption and release of four different standards. These standards pertained to the LCA principles and framework (ISO 14040), goal and scope definition (ISO 14041), life cycle impact assessment (ISO 14042), and life cycle interpretation (ISO 14043). The ISO standards were found to have limitations in their applied methodology and consultation process, leading to potential ambiguities. As a result, the UNEP/SETAC Life Cycle Initiative was launched to evaluate alternative practices and provide scientifically grounded recommendations. This need for improved consistency and reproducibility of LCA results also led the European Commission to initiate the development of the International Life Cycle Data System (ILCD) in the mid-2000s. The ILCD system includes a database of life cycle inventory data and methodological guidelines aimed at ensuring greater consistency and comparability of LCA results across different studies and practitioners. [1] [2]

Steps to perform an LCA

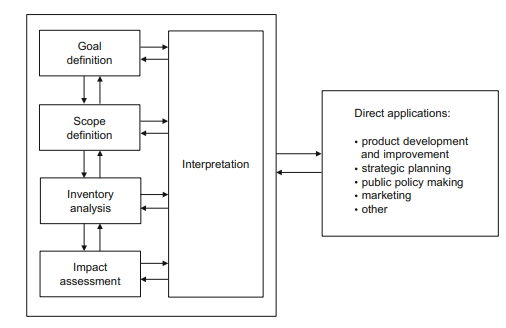

In the following paragraphs are listed the steps that have to be carried out in order to perform a well structured LCA study. These are, as well, the most important parts that must be included in an LCA report that can be considered detailed and professional. The LCA process is a systematic, phased approach and consists of four components: goal definition and scoping, inventory analysis, impact assessment, and interpretation. [3]

Goal and Scope definition

During the goal and scope phase of a study, the objectives are established, including the intended audience, the reasons for conducting the study, and the intended application. This phase involves making key methodological decisions, such as defining the functional unit precisely, identifying the system boundaries, determining allocation procedures, selecting the impact categories to be studied, choosing the Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA) method to be utilized, and establishing data quality requirements.

Functional unit

A lot of attention must be given to the definition of the functional unit, that is the base to calculate all the inputs/outputs of the analysed product and the relative emissions to the environment. The functional unit must be very specific and detailed. An example of functional unit may be : one car of type X, expected to be used for Y years, produced in country Z, with features a,b,c (e.g., how many people it can carry, desired performances etc.).

System boundaries

System boundaries define which life cycle stages are included in the study. In case of a cradle-to-cradle LCA, all the life cycle stages are taken into consideration, from the extraction of raw materials to use phase and disposal. However, in some studies it can happen that some processes are considered to have irrelevant impacts, or that the available data are not enough to model the process, or also, in the case of a comparative LCA, they are considered to have the same impact for both scenarios. Given that, such processes can be excluded from the study, at the condition that the reason of the choice is based on accurate evaluation and well argued.

Impact categories

The impact categories taken into consideration depend on the choice of the authors, that can have more interest in assessing e.g., the impact on climate change rather than on human toxicity. However, the choice of the LCIA method have an influence on that since some impact categories are not included in all methods. The most common impact categories are the following : Climate Change, Eutrophication, Resource Depletion, Land Use, Acidification, Ozone Depletion, Ecotoxicity, Ionizing Radiation, Water Depletion, Human Toxicity, Photochemical Ozone Formation.

Inventory analysis

The Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) phase encompasses the process of gathering and calculating data to measure the inputs and outputs of the system being studied. This includes collecting data on energy, raw materials, products, co-products, waste, emissions to air/water/soil, and other environmental factors. The collected data includes both foreground processes, which are the ones on the direct control of the producer (such as manufacturing and packaging of a product for a consumer good) and background processes (such as the production of purchased electricity and materials for a consumer good). The data is then verified for accuracy and related to the process units and functional unit, and they are the basis for the calculation of the environmental impacts of the product system.

Impact assessment

During the Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA) phase, the results obtained from the LCI phase are linked to various environmental impact categories and corresponding indicators. LCIA implies multiple steps and calculations, that are normally carried out by the LCA software, which also provides the user with a representation of the results in the form of a process tree, a table or a chart.

Classification

Classification requires assigning all the emissions to the relative impact category. For example, all the emissions of greenhouse gases (CO2, Methane, etc.) are associated to the Climate Change impact category.

Characterization

Characterisation involves calculating the magnitude of each input and output towards its respective impact category, and then adding up these contributions within each category. This is done by using substance- or resource-specific characterisation factors that quantify the impact intensity of a substance compared to a reference substance, which allows the calculation of the relative impact category indicator(s). By doing this, all the emissions relative to an impact category are aggregated into one unit of measure. For example, all greenhouse gas emissions are multiplied by a characterization factor that represents in terms of impact intensity relative to carbon dioxide, and therefore represented as an aggregated value of kg CO2 equivalent. The obtained results are called midpoints, which can be further aggregated into 3 areas of protection, obtaining endpoint results. “Midpoint indicators focus on single environmental problems, for example climate change or acidification. Endpoint indicators show the environmental impact on three higher aggregation levels, being the 1) effect on human health, 2) biodiversity ( or ecosystem health) and 3) resource scarcity. Converting midpoints to endpoints simplifies the interpretation of the LCIA results. However, with each aggregation step, uncertainty in the results increases.” [4]

Normalization

The purpose of normalization is to provide a relative scale for comparing the environmental impacts of different products or processes within the same impact category. By expressing the impact results in relation to a reference unit, normalization enables meaningful comparisons to be made between different LCAs. During normalization, the impact scores are divided by a reference value or factor to obtain a dimensionless score that represents the magnitude of the impact relative to the reference unit. Normalization factors can be based on a variety of sources, including government statistics, multi-criteria decision analysis, expert judgment or stakeholder consultation. The choice of normalization factors depends on the specific impact category being assessed and the availability of appropriate data. According to ISO 14040 standards, normalization is an optional step. However, it can be very useful to visualize more clearly which processes have more influence within each impact category. It ensures that the results obtained from LCIA are presented in a consistent and meaningful way that can inform decision-making and help identify areas for improvement.

Weighting

Weighting is another step that is considered to be optional by the ISO 14040 standards. It is the final step in a LCA and involves assigning relative importance to the different impact categories identified in the LCIA phase. The purpose of weighting is to combine the normalized impact scores of each impact category into a single score that reflects the overall environmental performance of the product or process being assessed. Weighting is necessary because the normalized impact scores are dimensionless and cannot be directly compared to each other without some form of normalization. The result of the weighting process is a single score that can be used to compare the environmental performance of different products or processes on a common scale. However, it is important to note that the weighting process involves subjective judgments and can be influenced by the values and preferences of different stakeholders. Therefore, transparency and stakeholder engagement are critical to ensure that the weighting process is fair and credible.

Interpretation

Life cycle interpretation is a systematic technique to identify, quantify, check, and evaluate information from the results of the LCI and/or the LCIA. Although the interpretation’s results are usually presented at the end of the LCA report, such a technique should be applied after each phase of the study, in order to identify potential issues and uncertainties. The outcome of the interpretation phase is a set of conclusions and recommendations for the study. According to ISO 14040:2006, the interpretation should include 3 steps: Identification, Evaluation, Conclusions, limitations, and recommendations. [5]

Identification

The purpose of the first element of the interpretation phase is to analyze the result of earlier phases of the LCA in order to determine the most environmentally important issues, i.e., those issues that have the potential to change the final results of the LCA.

-Goal and Scope definition: methodological choices and assumptions, such as the choice of the functional unit, the way of handling multifunctional processes and the boundary setting (if the case, also excluded processes)

-Inventory analysis: data for activities occurring in many parts of the product system, data for processes that contribute substantially to the environmental impact of the product system, data for elementary flows that contribute substantially to the overall score of an impact category.

-Impact assessment: characterization or normalization factors used in LCIA, the choice of the impact assessment itself, and of the impact categories to be considered. [6]

Evaluation

Evaluation consists of determining and specifying confidence in, and the reliability of, the results of the LCA or the LCI study, including the significant issues identified in the first element of the interpretation. During this step, it is necessary that the different issues are given attention that is proportionate to the influence that they could have on the final conclusions. The results of the evaluation should be presented in a manner that gives the commissioner or any other interested party a clear and understandable view of the outcome of the study. The evaluation involves completeness check, sensitivity/uncertainty analysis, consistency check.

-Completeness check: for LCI and LCIA, determine the degree to which the available data is complete for the processes and impacts, which were identified as significant issues. If the missing data are important to satisfy the goal and scope of the LCA, the inventory and impact assessment must be revisited in order to fill the gaps. If this is not possible or very demanding, the goal and scope definition may have to be adjusted to accommodate the lack of completeness. If neither of the options is possible, this should be considered when formulating the limitations of the study. In case the missing information is found to be of little relevance, this has to be stated in the completeness check.

-Sensitivity and uncertainty analysis: sensitivity of the model is defined as the extent to which a variation of an input parameter or a choice leads to a variation of the model results. Sensitivity analysis is often conducted by calculating a sensitivity coefficient for each impact parameter. The procedure consists of perturbating each model parameter by an amount that can be considered aligned with the uncertainty of such parameter, or by the same percentage for all parameters (e.g., 10%). Next step is to calculate the coefficient using this formula : (∆IS/IS)/(∆ak/ak) , where ∆ak is the perturbation of the parameter k, ak is the original value of the parameter, ∆IS is the difference measured in the impact score value after perturbating the parameter k and ∆IS is the original value of the impact score. In a very general way, uncertainty may defined as the degree to which we may be off from the truth. The overall uncertainty of a model results can be disaggregated into four components: parameter uncertainty, model uncertainty, scenario uncertainty ( choices and preferences) and relevance uncertainty ( relevance and representativeness of the indicators used).

The combination of sensitivity and uncertainty analysis helps identify focus points for improved inventory data collection or impact assessment.

-Consistency check: it is performed to investigate whether the assumptions, methods, and data, which have been applied in the study, are consistent with the goal and scope. If inconsistencies are identified, their influence on the result of the study is evaluated and considered to draw conclusions from the results.

Conclusions, recommendations and limitations

The conclusions should be drawn in an iterative way. Preliminary conclusions can be drawn based on the identification of significant issues and the evaluation of these for completeness, sensitivity and consistency. It is then to be checked whether the conclusions are in accordance with the requirements of the scope definition of the study. If so, they can be kept as final conclusions, otherwise they must be re-formulated and checked again. Soecifying the limitations of an LCA study is also of vital importance, as it increases its credibility and provides with important information about its usability.

Applications of LCA in Project, Program and Portfolio Management

In order to better understand the role of LCA in Project, Program and Portfolio Management (PPPM), it is necessary to introduce the concept of Life Cycle Management (LCM), that can be defined as "a management concept applied in industrial and service sectors to improve products and services while enhancing the overall sustainability performance of a business and its value chains." (G.Sonnemann, M.Margini, chapter 2). [7] In other words, LCM means integrating a sustainability-oriented, holistic view on the life cycles of products, service activities and systems into managerial decision-making processes. LCA, as a tool of LCM, is being applied by several companies (especially in the last decade) to take better and more informed decisions, which is a fundamental aspect in PPPM. As an example, LCA can be particularly useful when starting a project, to decide which products, materials or procedures are better from an environmental point of view. In addition, Organisational LCA can be used to evaluate the environmental performance of suppliers and other partner organisations, to decide who to cooperate with during the implementation of a project. LCA is also very relevant in Portfolio Management, as it provides a basis for comparison between projects when deciding which ones to prioritize, as well as between different investment opportunities. To maximize the usefulness of LCA in decision-making processes, it should be used in combination with some or all the other LCM tools, which are Life Cycle Costing, Social LCA and Sustainable Product Design. [7] LCA is also a tool to enable change, as it can be used to assess the need of change in an organization. Enabling change to achieve the envisioned future state is one of the Project Management principles included in the "Guide To the Project Management Body of Knowledge, The standard for project management", publiced by the Project Management Insitute. [8]

Strenghts and limitations

LCA's main strength lies in its comprehensive life cycle perspective and broad coverage of environmental issues, which enables the comparison of environmental impacts of product systems that comprise numerous processes and involve thousands of resource uses and emissions occurring in different locations and at different times. However, this comprehensiveness is also a limitation as it requires simplifications and generalizations in the modeling of product systems and environmental impacts, preventing LCA from calculating actual environmental impacts. Therefore, it is more accurate to say that LCA calculates impact potentials, considering uncertainties in mapping resource uses and emissions and in modeling their impacts over time and space.

Another strength of LCA, in comparative assessments, is that it follows the "best estimate" principle, ensuring unbiased comparisons through the same level of precaution applied throughout the impact assessment modeling. However, this principle's limitation is that LCA models are based on the average performance of processes and do not consider rare but catastrophic events such as marine oil spills or industrial accidents.

Moreover, LCA cannot tell if a product is environmentally sustainable in absolute terms or if a product is "good enough" environmentally, even if it has a lower environmental impact than another product. Therefore, LCA is suitable for answering some questions and not suitable for answering others, and its limitations should be kept in mind when interpreting its results. For example, LCA can tell us what is the most environmentally friendly option between a plastic bag or a paper bag to carry groceries back home from the supermarket. Although, it cannot tell us if a government should increase taxes on internal combustion vehicles to lower the emissions and therefore save money from lungs cancer treatments. That is because LCA cannot evaluate the social impact of increasing taxes with the positive environmental impact of lowering pollution. In this case, a Cost Benefit Analysis should be combined with Health Assessment Studies to better answer this question. [9]

Annotated Bibliography

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Life Cycle Assessment:Theory and Practice, chapter 3 (Michael Z. Hauschild, Ralph K. Rosenbaum, Stig Irving Olsen) https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-319-56475-3

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 M.L. Brusseau, Chapter 32 - Sustainable Development and Other Solutions to Pollution and Global Change,Editor(s): Mark L. Brusseau, Ian L. Pepper, Charles P. Gerba, Environmental and Pollution Science (Third Edition),Academic Press,2019,Pages 585-603,ISBN 9780128147191,https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-814719-1.00032-X. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B978012814719100032X)

- ↑ European commission website, https://eplca.jrc.ec.europa.eu/lifecycleassessment.html#:~:text=LCA%20is%20based%20on%204,impact%20assessment%2C%204)%20interpretation.

- ↑ National Institute for Public Health and the Environment Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport; LCIA: the Recipe model; https://www.rivm.nl/en/life-cycle-assessment-lca/recipe"

- ↑ Patxi Hernandez, Xabat Oregi, Sonia Longo, Maurizio Cellura, Handbook of Energy Efficiency in Buildings, A Life Cycle Approach (2018), chapter 4; https://www.sciencedirect.com/book/9780128128176/handbook-of-energy-efficiency-in-building

- ↑ C. Cao, Advanced High Strength Natural Fibre Composites in Construction (2017), chapter 21.4.2.4; https://www.sciencedirect.com/book/9780081004111/advanced-high-strength-natural-fibre-composites-in-construction

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Guido Sonnemann, Manuel Margini, et.al.; LCA Compendium- The Complete World of Life Cycle Assessment (2015)

- ↑ Project Management Institute Inc.; A Guide To the Project Management Body of Knowledge, The standard for project management, chapter 3.12 (2021)

- ↑ Life Cycle Assessment:Theory and Practice, chapter 2.3 (Michael Z. Hauschild, Ralph K. Rosenbaum, Stig Irving Olsen) https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-319-56475-3