A product rationalization project part of a portfolio optimization program

(→The rationalization categories) |

|||

| Line 155: | Line 155: | ||

|- | |- | ||

|rowspan="2"|'''Removing the "sacrificial sinners"''' | |rowspan="2"|'''Removing the "sacrificial sinners"''' | ||

| − | | | + | |rowspan="2"|Unprofitable |

| − | | | + | |rowspan="2"|Medium |

| − | | | + | |rowspan="2"|Many |

|High revenue substitutability | |High revenue substitutability | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 168: | Line 168: | ||

|Very high revenue substitutability | |Very high revenue substitutability | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

===Step 4 - Capture=== | ===Step 4 - Capture=== | ||

Revision as of 12:55, 16 September 2016

Product proliferation enables organization to serve customers´ varying requirements and needs as well as attracting new customers. By expanding the product portfolio organizations can capture new revenue sources and build and sustain a competitive advantage. Some organizations pursue the strategy of diversifying the product portfolio without fully understanding the extent to which implications can occur e.g. as new product variants are added complexity increases and higher costs are introduced in the supply chain.

When the portfolio consists of too many products, it becomes critical to the cost competitiveness of the organization to effectively manage and control the products in the portfolio. Through intelligent product rationalization by focusing on revenue substitutability, linked revenue and a lifecycle perspective, it is possible to minimize revenue loss but ensure significant cost reductions, hence reducing complexity in the portfolio.[1] Additionally, prioritization and selection of products becomes essential to ensure alignment with the business strategy.

SKU rationalization is central to reduce complexity costs and thereby optimize and control the portfolio. Many companies have adopted complexity management approaches to reduce complexity costs and increase competitiveness. The aim of this article is to examine thoroughly the use of portfolio optimization in regards to SKU rationalization as a method to reduce complexity, control the portfolio and release resources. As a result, it is possible to maximize the strategic organizational goals by reinvesting in future projects to strengthen the portfolio while obeying budgetary restrictions.

Contents |

Background

SKU rationalization is the process of eliminating projects that contributes negatively to the strategic organizational goals. Before SKU rationalization is elaborated, it is important to understand how product proliferation and poor portfolio management in tandem introduce complexity, why rationalization is a powerful tool in the process of regaining control over the portfolio, and when it is applicable to your business.

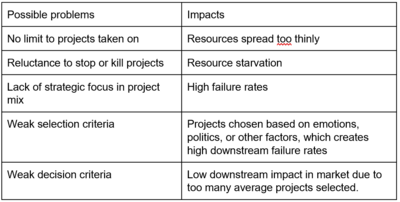

When organizations proliferate their product variety to fulfill the market demand but also to establish barriers to entry as it leaves little space for potential entrants.[3][4] This enables organizations to prevent entry in mature markets as well as capturing new revenue sources and sustaining profitable growth through a competitive advantage.[5][6] When expanding the product diversity without proper portfolio management several problems may occur. The problems in table 1 is a result from incoherent evaluations of new projects which fail to both review economic and non-economic risk and rewards across a set of projects and to ensure the projects are balanced in the portfolio.[2]

Industry example of rationalization and benefit

What is complexity?

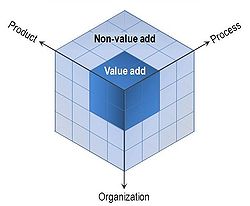

The complexity cube framework describes how complexity develops from three interdependent dimensions. The ability to understand and identify from where complexity develops in the specific organizations increases the ability to analyze and remove it. The key takeaway from the complexity cube, see figure 1, is that the issues of complexity originates from the intersections between the dimensions and the costs associated with complexity is multiplicative between the dimensions, hence the effort to reduce complexity should be focused on multiple dimensions to create impact. The complexity costs grow exponentially with greater levels of complexity, hence organizations that can deliver good complexity and reduce or even eliminate bad complexity will create a sustainable competitive advantage. They will create an advantage because they will be significantly more profitable and the skills to manage complexity are difficult to replicate.[1]

This article focuses on the complexity that arise between products and processes and introduces a rationalization method to regain control of portfolio and to reduce the level of accumulated complexity organization, as rationalization of the portfolio is central to do so.[1]

How to regain control and fight complexity

How do you know if your have complexity?

The 5 step approach

Step 1 - Defining the scope

The first step in regaining control over the portfolio is to define the scope of the program. Defining the scope of the project starts by the top management or the PMO appointing a project team to be responsible. The project team then conducts a stakeholder analysis. The project team determines collaboration with the key stakeholders the scope of the project and takes into consideration the time and resources available. To delimit the project, it is essential determine what product families and product variants to include as well as the level of detail i.e. finished good, module or component level. Additionally, it is important to select where the cost-saving effort should be focused e.g. which life cycle processes and what principles that will guide the effort. When collecting data, it is also important to decide what the given time period is and from what geographical area. Ensure that the project is successful, key performance indicators are set up, which should focus financial data, lead time, the quality of the products etc. One the scope has been determined, the project team develop a plan for the project. In planning the project, it is critical to identify stakeholders that can participate in various workshops and participate in the decision-making process when the elimination of product variants is taken place.

Step 2 - ABC analysis

The ABC analysis helps to determine which product variants that does not add value, hence can be removed. When the rationalization is carried out, more factors i.e. incremental revenue, incremental costs and a life cycle perspective, are added to ensure maximum cost reductions and minimum revenue loss. The ABC analysis is a critical tool that creates the baseline for the rationalization. The ABC analysis focuses on dividing the products into A, B and C categories respectively. To categorize the product variants, the Pareto distribution is used based on its revenue and contribution margin (Koch, 2008). The product variants accounting for 80% of the revenue and contribution margin are in category A. Product variants that contribute to the next 15% of the revenue and contribution margin are in category B. Category C products account the remaining 5% of the revenue and contribution margin. There will be product variants that will be outside of the categories when a double Pareto analysis is conducted. These product variants are then individually assessed and put into the category where it fit best. The product variants are plotted in a diagram with logarithmic scale where the contribution margin are represented on the vertical axis and the revenue on the horizontal axis.

Revenue

To calculate the revenue per product variant, sales information is collected for a given time period and adjusted for deviations arising from customs, currencies and discounts. Then the sales added together to calculate correct revenue per product variant.

Contribution margin

The contribution margin is calculated by gathering the variable costs for each product variant. Additionally, the most significant complexity costs, i.e. a portion of the fixed costs, are deducted. The biggest exercise is then to identify, quantify and allocate the complexity costs to provide a clear picture of the product variants´ true performance. It is important to focus the collective effort on the most significant complexity cost factors to execute the project for efficiently. The reason why not all complexity cost factors is included is because of the 80/20 costing principle. By adjusting the contribution margin approximately 20% with the most significant complexity cost factors, 80% of the answer is given. (Waging war on complexity). It is key to the identification of the complexity cost factors to identify the cost areas with an uneven distribution of costs between the product variants. The process of identifying the significant complexity cost factors can be started with a brainstorm. After the possible significant complexity costs have been identified, they are analyzed, quantified and allocated directly to the specific product variants, based on activity based costing. If the complexity costs are difficult to quantify, you can find quantification objects that allow approximations where it is possible. It can be necessary to creatively apply unconventional quantification objects to reliable complete incomplete data sets. When the different costs are calculated comparable percentages can be calculated by dividing all costs by the net revenue for each product variant. If the analysis shows a clear uneven distribution of costs, then the significant complexity costs are deducted from the contribution margin. The adjusted contribution margin per product variant is used for the ABC analysis.

Example

Step 3 - SKU rationalization

The next step after constructing the ABC diagram is to decide which product variants to remove from the portfolio. The goal is to create a portfolio, whose offerings are focused on what customers. To do so, the rationalization is split into 4 categories that is based the product variants performance but equally focuses on two important principles; incremental revenue and a life cycle perspective.

The principles

Incremental revenue

Incremental revenue is the revenue that will be lost if the product variant in question was eliminated. The relationship between the incremental revenue and the two factors, revenue substitutability and linked revenue, which is described below, is expressed by:

Incremental Revenue = Revenue x (1 – Revenue Substitutability) + Linked Revenue

Identifying the incremental revenue is essential to product rationalization. By adding incremental revenue to the scenario it is possible to remove product variants with reasonable revenue but low incremental revenue, due to the high revenue substitutability. This limits the revenue loss however it also adds revenue to the remaining products. This result in both reduced complexity, as the complexity cost associated with the deleted product variant is eliminated and the existing complexity costs will be less expensive as it will be spread over more revenue due to the revenue substitutability from the eliminated product variant. (Waging the war)

Revenue substitutability

Revenue substitutability is an important principle. It is the extent to which customers will transfer their purchase from one product to another if the product variant no longer was part of the portfolio. The revenue substitutability is expressed as a percentage. The benefit of identifying the revenue substitutability is opportunity to find product variants with a high revenue substitutability. Product variants with a high substitutability are likely to be eliminated as the revenue loss will be minimum whereas the complexity associated with the eliminated product variant will be eliminated. Estimating the revenue substitutability can be difficult. However, an informed estimate be okay. Adding rough estimates to the scenario is better than assuming zero substitutability.

Linked revenue

Linked revenue means the revenue from the sales of other product variants in the portfolio that would be lost if the questioned product variant was eliminated. The linked revenue may be higher than the revenue related to itself. The product variants with a high linked revenue can be called door openers. When doing the elimination of the product variants it is good to assume zero linked revenue. This is because organizations tend to believe that they more door openers than the customers think. Adding linked revenue should serve to separate real door openers from the imposters.

A life cycle perspective

If the rationalization is only based on the current performance of each product variant and the incremental revenue, the decisions for the portfolio rationalization is only based on the current performance. The strategic incentives to start a cost reduction program is to ensure long term growth. Therefore, life cycle considerations are important for two reasons.

- To ensure that the portfolio optimization not only focuses on past financial and operational data but takes the future performance into considerations.

- Enable the establishment of an evaluation sequence of product variants. A categorization method could be the Boston Matrix.

It is therefore very important for the future growth of the business to develop precedence where the dependence between products and their relative future attractiveness are considered.

The basic understanding of the underlying rationalization principles has been established. The next step in the process is to make decisions regarding which product variants to eliminate and which product variants to keep in the portfolio.

The rationalization categories

The process of elimination is described in table xx- Categories of SKU Rationalization. The categories are used to divide the product variants into removal categories. The volume of product variants that should be eliminated depend on the above described principles and analyses.

Cleaning the attic

The product variants that have been left in the portfolio but effectively have no activity belong in this category. Removing the attic creates a better overview, creates space and can provide some quick gains. The pitfall is that organizations focus on the number of product variants eliminated rather than the impact made however it removes noise from the portfolio.

Small losers

The small losers are characterized by having small revenue and volume per product variant. The small losers are all unprofitable and large in numbers. Removing the small losers will reduce the level of complexity in the portfolio however it will not make the remaining complexity cheaper because their removal will not add significant revenue to the remaining product variants. The majority of the small losers should be removed except product variants that are early in their life cycle and have a promising future.

Sacrificial sinners

Profitable product variants that are shown to be unprofitable when the contribution margins are adjusted with the significant complexity costs are called sacrificial sinners. Sacrificial sinners will have medium revenue per product variant. Sacrificial sinners with high revenue substitutability that have the opportunity to turn other unprofitable product variant profitable should be removed. Additionally, product variants with low revenue substitutability that cannot become profitable and do not have any linked revenue should also be eliminated. Removal of sacrificial sinners create big impact by removal of complexity and transferred revenue that minimizes the revenue loss.

Silent killers

Silent killers are profitable and have large revenue per product variant. The silent killers are characterized by having almost 100% revenue substitutability. The incremental revenue is very small or zero. The silent killers consume a large amount of resources, hence removing the silent killers have great impact as large costs can be removed while revenue are preserved. The number of silent killers that should be removed will significantly depend on the industry but typically be few in numbers.

| Categories of Product Rationalization | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Product removal categories | Types of products in scope | Portion that should be removed | Characteristics of products that should be removed | ||

| Profitability | Typical revenue per product variant | ||||

| "Cleaning the attic" | Product variants for which there is essentially no activity | All | All | ||

| Removing the "small losers" | Very profitable | Small | Majority | All, except product variants that are in the beginning of their product lifecycle | |

| Removing the "sacrificial sinners" | Unprofitable | Medium | Many | High revenue substitutability | |

| Cannot become profitable by the removal of other product variants | |||||

| Removing the "silent killers" | Profitable | Large | Some | Very high revenue substitutability | |

Step 4 - Capture

the value /Develop implementation plans

step 5 - Sustain

Evaluate complexity reduction from other projects

Implications

How to fight complexity creep

Focus on all aspects of complexity

Capability building Selection and decision models Other courses of complexity

==

Testing referencing.[8]

Annotated bibliography

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Wilson, A. S., & Perumal, A. (2010). Waging war on complexity costs. McGraw-Hill.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Tidd, J. and Bessant, J. (2013) Managing innovation: Integrating technological, market and organizational change. 5th edn. United States: Wiley, John & Sons. Page 338-339.

- ↑ Schmalensee, R. 1978. Entry deterrence in the ready-to-eat breakfast cereal industry. Bell Journal of Economics, 9: 305–327.

- ↑ Smiley, R. 1988. Empirical evidence on strategic deterrence. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 6: 167– 180.

- ↑ Mascarenhas, B., Kumaraswamy, A., Day, D., & Baveja, A. 2002. Five strategies for rapid firm growth and how to implement them. Managerial and Decision Economics, 23: 317–330.

- ↑ Pichler, H., Vienna, Dawe, P. and Edquist, L. (2014) Less can be more for product portfolios. Available at: https://www.bcgperspectives.com/content/articles/lean_manufacturing_consumers_products_less_can_be_more_product_portfolios/.

- ↑ Perumal, W. and Company (2013) How is complexity impacting your retail business? Available at: http://www.wilsonperumal.com/blog/how-is-complexity-impacting-your-retail-business/.

- ↑ Remember that all the texts will be included into the reference containing the name= attribute.