Managing projects in a functional organization

(→Organizational structure) |

(→Introduction and background) |

||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

In order to discuss the role of the project manager in a functional organization, it is necessary to understand what a functional organization is. The next section introduces the general types of organizational structures along with the roles of the project manager in each structure. | In order to discuss the role of the project manager in a functional organization, it is necessary to understand what a functional organization is. The next section introduces the general types of organizational structures along with the roles of the project manager in each structure. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

Revision as of 19:02, 20 February 2019

Contents |

Abstract

Functional organisations, where the employees are grouped based on skills and job type, are useful to increase knowledge sharing within the groups. I.e. a functional group with programmers allows the programmers to help and learn from one another during working hours. This results in more specialized groups with self-increasing skills, though limiting the connection between people with different skill sets. Divisional organisations, where the employees are divided into groups based on location, product or market instead, have a broad variety of people with different skills in each group. This allows for better interactions among the different skill sets during working hours but takes away the knowledge sharing with like-minded people. [1]

Projects are generally complex and require people with various skills to be done. Thus, the divisional organisation structure seems like the better fit for projects, as the need for inter-group communication is far less crucial. In a functional organization, all groups involved with the project have to be in close communication with one another in order to maintain a common direction for the project. This is where the project manager becomes important.

This article highlights the common challenges that a project manager must deal with when doing projects in a functional organization.

Introduction and background

Managers deal with numerous different challenges and problems when supervising the employees and trying to set and achieve departmental goals while also complying with the goals and strategy of the organization. This applies to both functional managers and divisional managers. In this article, the focus is on the challenges that project managers face in functional organizations, in particular with cross-functional projects.

In order to discuss the role of the project manager in a functional organization, it is necessary to understand what a functional organization is. The next section introduces the general types of organizational structures along with the roles of the project manager in each structure.

275

Organizational structure

The term "organizational structure" covers the formal system of task and job reporting relationships between employees and how the organizations resources should be spent to obtain its goals. The structure is determined by managers, typically based on the four factors described by the contingency theory; organizational environment, strategy, technology and human resources. This process is described by the term "organizational design" which includes job design (division of the tasks required to run the organization into jobs) and design of the organizational structure.

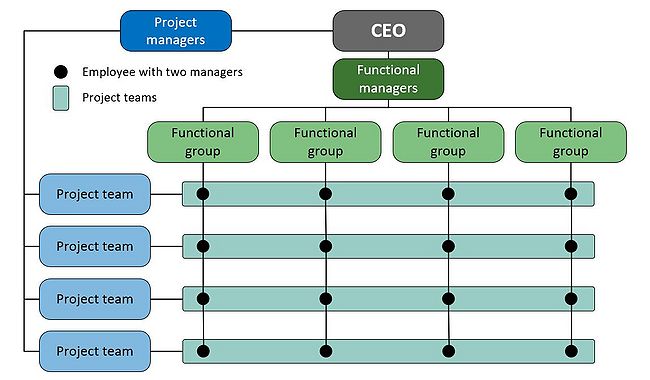

Overall, there are two distinct types of organizational structures; divisional and functional. However, large and complex organisations can create matrix structures which combine divisional and structural elements (see Figure 1). The final design is determined so that it maximizes the efficiency and effectiveness of the organization.

Functional structure

Grouping the jobs based on skill requirements, so that employees with resembling skill sets work together, is the idea of the functional structure (green part of Figure 1). A functional organization is composed of all the departments that are required for the organization to deliver its products, being goods or services. This structure makes it easy for functional managers to evaluate the performance of the employees in their respective departments, since all their employees can be evaluated on the same factors. Furthermore, each department can be more specialized due to knowledge-sharing among the employees. [1]

A car manufacturing company with a functional structure would include a marketing department, a procurement department, a production department and an engineering department etc. The performance of each department in this structure would be higher compared to a divisional structure. Tasks that are completed within the departments might often share common attributes and will be completed faster due to increased collaboration among like-minded employees.

From an ideal point of view, the functional structure provides the highest performing departments. However, when doing cross-functional projects challenges appear in the functional structure. Every employee is used to respond to their functional manager and is possibly occupied with certain departmental tasks that the functional manager has planned. When the employee is assigned to a project with a project manager, the employee now responds to two managers. This can be a source of conflict within organizations if there is no clear hierarchy among the managers or if the managers can not come to agreement regarding division of the employee's working hours.

Divisional structure

However, when organizations grow too large and begin to produce a wider range of goods or services and deal with a larger variety of customers, functional managers might become so busy supervising their departments and keeping up with departmental goals, that they lose sight of the organizational goals and strategy. This reduces efficiency and effectiveness and this is where the divisional structure becomes useful (blue part of Figure 1).

Rather than having large functional units dealing with large numbers of different tasks, divisional departments can be implemented to split the number of tasks out to i.e. product specific departments. Instead of having a marketing department that sells all types of products from the organization, there would be departments for each product type, employing a limited number of marketing experts along with production-, engineering-, and procurement experts with focus on these particular products. The product manager would then have a more manageable amount of tasks to supervise. Though, the cost of this structure is the lack of knowledge-sharing and departments with lower levels of skill development.

However, it is a necessary structure to keep the departments aligned with the organizational strategy and to provide the highest possible level of efficiency and effectiveness. As a side benefit, doing cross-functional projects in a divisional structure can be easier, since a project can be contained within a department instead of being cross-departmental.

Project management in functional organizations

Pending...

Good practices

Common challenges

Limitations

Annotated bibliography

The Essentials of Contemporary Management, Chapter 7 (Sixth Edition)

This chapter describes the process of which managers choose organizational structures and what these structures are. It describes benefits and disadvantages to the common structure types and why managers need to solve related issues.