Project Evaluation and Selection for the Formation of the Optimal Portfolio

The increasing intensity of competition and fast technology changes make firms look for the development of more innovative products. In order to keep up with market trends and to stand out from competitors, most of the companies in technological fields turn to the development of R&D projects. Generally, these are risky due to the uncertainty surrounding its technological feasibility and its future commercial success, which make their evaluation and selection difficult to achieve. Nevertheless, the survival of an organization is highly correlated with correct project selection and management (Ashrafi, 2012). A wide diversity of approaches have been developed and used throughout recent years in order to cope with this problem, each of them with its own advantages and disadvantages. The most common are quantitative methods, qualitative methods and hybrids methods (Ashrafi, 2012). Nonetheless, most of the times not only one method is used during the evaluation process.

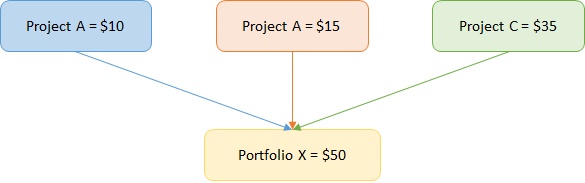

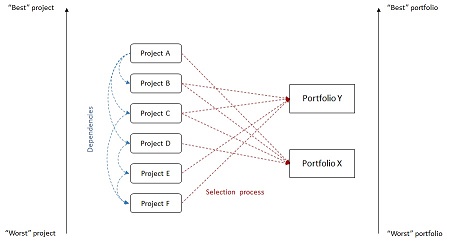

Even if the projects are correctly evaluated separately, this does not guarantee that the best portfolio can be formed. The best portfolio is the one that maximizes the probabilities of achieving the goals set by the company (Chien, 2002). Its formation is not just about evaluating independent projects; it is about evaluating the whole portfolio itself. Choosing the best projects based on financial or any other criteria may not result in the best portfolio due to dependencies or interrelations that may exist between the projects. The most common of them are related to cost, resources, financial return and technical factors (Blau, 2004), as well as outcome and impact dependencies. The problem of evaluating and selecting projects and scheduling them is complicated further by their presence. These dependencies add complexity to the decision that needs to be taken, since the decision-making process becomes less straightforward. A good example is the impossibility of using some quantitative methods, like linear programming. A good example of this situation is given when investing an additional monetary unit, since it may have impact in more than one project, since the additive restriction does no longer exists under this perspective. In consequence, a difference between measuring the preference for the portfolio as a whole and measuring the preferences for projects in the portfolio (Chien, 2002), and it may be also the case where the objectives that are considered when evaluating portfolios are different than those used when selecting individual projects.

If a company decides to evaluate a portfolio as it would evaluate projects, the amount of time required would be unmanageable. With only a set of 10 projects, the decision-maker would need to evaluate 1024 portfolios (Ghapanchi, 2012), which would be impossible for most of the companies (the possible combinations of projects equals 2 to the x power). In consequence, newer methods have been developed to assist with choosing the best portfolio within a shorter time. This article focuses on describing and analyzing these methods.

Contents |

Background

Application context

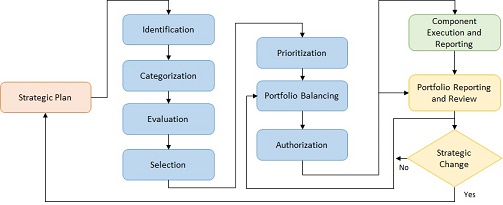

Every organization has an specific business strategy that will enable its employees to reach its long-term goals. In consequence, ideas and concepts are developed, and products and services are designed, produced, manufactured and sold. However, companies need to take decisions along this path, since they do not have unlimited resources for pursuing every single idea. Furthermore, every one of them has a benefit accompanied by a certain degree of risk. Nevertheless, frequently, both benefits and risks are difficult to measure, since perfect information is not always (almost never) available. Selecting the best projects (according to different criteria, like expected benefits, risk, investment, return, among others) is a common practice among many enterprises, no matter the industry they belong to. At the same time, projects can be of very different origin. Some of the most discussed in the literature are R&D projects, New Product Development, marketing campaigns, among others internal activities. However, selecting the best project in order to form the optimal portfolio is not an easy task.

According to the Project Management Institute, a portfolio is "a collection of projects and/or programs and other works that are grouped together to facilitate the effective management of that work to meet strategic business objectives. The components of a portfolio are quantifiable; that is, they can be measured, ranked, and prioritized" (PMI, 2006). In that way, the optimal portfolio would be the one that, given a determined array of projects, gives the maximum benefits and is the one that best meets the company's objectives.

Development history

Few project selection models are being utilized as aids to decision making. The number of selection models, along with user interest in applying them, grew exponentially in the 1950's and 1960's; however, this trend has reversed since the mid-1970's (Chien).

Acceptance and use

Standards and surveys?

From Project Selection to the Optimal Portfolio

Traditional Methods for Project Evaluation

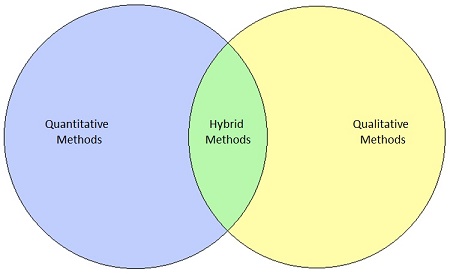

Three schools of thoughts have been identified (Ashraki) on how to classify the approaches for project portfolio selection:

- Quantitative Methods: these approaches, both for project selection and resource allocation, have been greatly developed since the early 1990's, but some of them have been around for more decades. However, they have been often criticized because their focus on numerical information, even though tacit knowledge and qualitative information have also been regarded as relevant. Generally, they can be classified in six dimensions (Iamratanakul,2008):

- Benefit measurement methods: Comparative models, scoring models and analytic hierarchy process. Here, five measures are particularly popular (Thamhain, 2014): Net Present Value, Return on Investment, Cost-Benefit, Pay-Back Period and Pacifico and Sobelman Project Ratings.

- Mathematical programming approaches: linear programming, non-linear programming, integer programming, goal seek, dynamic programming, stochastic programming and fuzzy mathematical models.

- Simulation and heuristic models: Monte Carlo simulation, heuristic modeling and system dynamics simulations.

- Cognitive emulation approaches: decision-tree, game-theoretical approaches, statistical approaches and decision process analysis.

- Real options: approach that incorporates both uncertainty and the active decision making required for a strategy to succeed.

- Ad hoc models: unstructured models built for specific purposes.

- Qualitative Methods: their focus is to take into account those factors that quantitative methods cannot. For project evaluations involving complex sets of business criteria, narrowly focuses quantitative methods are often supplemented with broader qualitative methods. Some of the most used are bubble diagrams, sensitivity analysis, benchmarking, check-lists, user centered design, group decision techniques and expert systems (Delphi, nominal group technology, focus groups). However, all of them can be used by themselves to determine the best, most successful or most valuable project.

- Hybrid (Mixed) Methods: they are the most common methods for evaluating and selecting projects nowadays (Thamhain, 2014). To qualify as a hybrid approach, the project evaluation and selection process has to contain a fairly balanced array of both classes of analytical and judgmental tools and techniques. Some good examples are graphical methods, conjoint analysis, data envelopment analysis and scenario planning.

Dependencies

In order to understand why dependencies or interrelations are relevant to this topic, and why the methods discusses above do not lead to an optimal decision, it is important to define what are these interactions. To begin with, it is worth noting that there are two sources of interactions among projects: internal and external factors. The former arises when the resource requirements and/or benefits of one project are significantly affected in magnitude and/or timing by the selection or rejection of one or more of the projects in the set. On the other hand, the external interactions are those that arise over time from social and economic changes which have effects over subsets of the project set (Fox et. al, 1984). Through this article, only the internal interactions are going to be discusses, since those externals are impossible to know/quantify beforehand by the decision-maker.

There are 4 major sources of internal dependencies: Costs dependency, (non-monetary) resources dependency, outcome or technical dependency, and impact or benefit dependency. Some of them may overlap in scope, but are different in essence.

Cost Dependency

It is also called resource-utilization dependency. This dependency arrises when the sum of the costs of two or more projects within a portfolio is not the same at the total cost of the entire portfolio. This happens because there is some degree of resource sharing, like labor, utilities, machinery and tooling, among others (Blau, Chien, Fox et. al). A project may require using a new machine, but its capacity is higher than the utilization required by this project, so it is possible to share it with other projects or with ongoing operations. However, if it is not used for something else, then the dependency does not exist. On the other hand, the appropriate portion of the cost of this machine is difficult to estimate, since it would be necessary to have an overview of the rest of the projects, some of whom might come in the future.

Resources Dependency

It is more related to the time that a certain project may require. It differentiates from the cost dependency because its focus is not the money employed, but the available time for its development. Its root cause is the learning curve derived from the employees' experience. A good example is that of the reduction in development times of two similar drug types (probably the second one will require less time because of the experience acquired during the development of the first one).

Outcome or Technical Dependency

This type of interactions occurs when the probability of success of a given project depends on the outcome (success or failure) of one or more of the other projects (Fox et. al and Chien). The problem for the decision-maker arises when trying to translate this situation to numbers or comparable criteria. This could be compared to decision-tree analysis: if an specific project fails, then the next project cannot be developed and vice versa. This type of dependencies are common in software or hardware development. A good example could be the case of a new printer that requires the development of a new technology for printing with twice the speed as the previous model. In this case, the printer cannot be released to market if the printing technology has not been successfully developed.

Impact or Benefit Dependency

An impact or benefit dependency may occur when the impacts of payoffs of the projects are not additive. In this case, projects may be said to be complementary or competitive, e.g. what happens with cannibalism. A good example for this dependency is what happens when a company decides to introduce a new product to a specific market segment, successfully increasing the overall sales. At the same time, another project's objective is to add a special feature that may make more attractive this same product in order to reach a different demographic group, which will also increase sales. If both projects are implemented, then the net total sales may be lower than the expected individual sales figure for each project. Since the product now has a scope for two markets, then some buyers may not consider it attractive anymore. (Fox et. al).

Methods for the Formation of the Optimal Portfolio

- Dependencies as in taken into account

- New methods

Related material

Comparable standards / recommendations

Obviously standards

Webpages or books

Discussion

Strengths and weaknesses

There are some limitations in the existing project selection models (Chien) for the further formation of portfolios:

- Inadequate treatment of multiple, often interrelated, evaluation criteria.

- Inadequate treatment of dependencies among projects.

- Inability to handle non-monetary aspects, for example, diversity among projects.

- No explicit recognition and incorporation of the experience and knowledge of the managers or decision makers.

- Perceptions by the managers that the models are difficult to understand and use.

Controversial points

Pro's and con's

Integration / relationship to other material

Relationship with resource allocation

Implementation advice

How to use and methods

Choosing the adequate one.